Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoCan we take the gas out of inflation in Georgia?

The Gist

Inflation — the increasing cost of goods and services — is causing pain and busting budgets across the country, and even more so for people in Georgia. While the Feds play the long game with interest rates, recent efforts by Gov. Brian Kemp and the state to control inflation so far are low impact, but good for morale.

What’s Happening

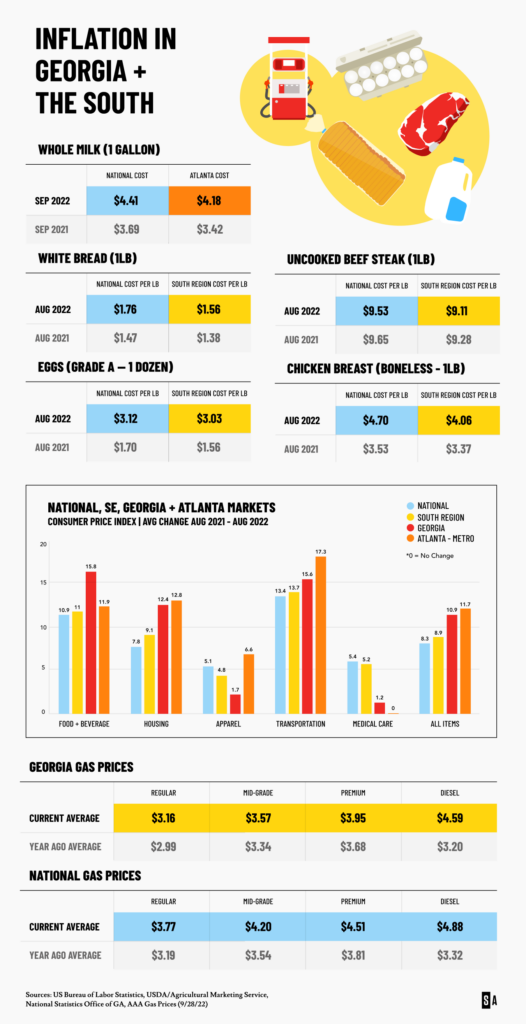

Over the last year, the rate of inflation has risen 8.3 percent in the U.S., 10.9 percent in Georgia, and 11.7 percent in metro Atlanta. The cost of groceries, fuel and housing is contributing mightily to the sticker shock that consumers are experiencing. Driving up those costs is an increased demand for all kinds of products by Americans, at a time when employment is high and the global supply chain is stressed.

“A hundred dollars just doesn’t go as far now,” says Ronekia Earley, 29, who was shopping at Piggly Wiggly in southeast Atlanta with her fiancé, Tereze Fortson, 30, and their son Aiden, 9, this week. They have three more children, ages 5 months, 1 and 3-years-old. “What used to last a month now only lasts two or three weeks,” she said. Their cart included packages of pork chops, chicken wings and a jar of mayonnaise with ‘Pick 5 for $24.99’ stickers.

“It used to be ‘Pick 5 for $19.99,’" said Fortson. “They’re shrinking the deal that we depend on.”

Last week, Federal Reserve Bank officials moved to flatten the spike in inflation nationwide by once more raising benchmark interest rates —now at 3% to 3.25% (the highest since 2008). The Federal Reserve will likely increase rates to 4.5% before they’re done raising them next year. This ongoing action by the Fed is expected to drive down demand for vehicles, housing and fuel, and put a damper on spending overall. It also greases the skids to an economic recession, according to many experts.

Earlier this month, Gov. Kemp continued his effort to curb inflation in Georgia by renewing executive orders to temporarily suspend fuel taxes, and relaxing some regulations related to supply chain management – chiefly around how long truck drivers can be on the road, and the size of the loads they can carry. These orders kicked off in March and now extend to Oct. 12.

The impacts of both orders by Kemp “are small, they’re at the margins,” says Marty Parker, a lecturer and supply chain expert at the University of Georgia. “But when you’re talking about a person living on a fixed income, or a business trying to manage a supply chain, the margins are important.”

Parker and other economic experts estimate that with the suspension of the 29.1 cents per gallon state gas tax, the average consumer in Georgia is saving $12 to $15 a month on gas.

That monthly fuel savings “is okay, a little something I put in my son’s piggy bank, to save it for when we might really need it,” said Earley, who works as a school janitor in Atlanta.

The state tax savings on diesel fuel — at 32.6 cents per gallon — can add up to more for small business owners, especially those operating their own trucks or fleets.

Maurice Garard, an owner-operator long haul truck driver based in McDonough, frequently drives several hundred miles at a time. This week at a QT truck fueling station in Forest Park, he filled up his rig stocked with dog food bound for Dallas. At $4.49 per gallon of diesel, he spent $706.69 for 157 gallons, saving $51.18 in state fuel tax.

Garard estimates he saves several hundred dollars a month from the diesel tax break, but said more relief has come from the steady drop in fuel prices since June, when diesel fuel peaked at $5.80 per gallon.

“Diesel prices coming down is critical, and props to the governor for his part in that,” said Garard. “But the cost of everything else is still really high. And if you need to repair your truck, good luck. There’s not enough parts in the market, or mechanics to do repairs.”

Garard said he recently spent $30,000 to have the motor rebuilt on his 53-foot Peterbilt truck, paying a mechanic $150 an hour. He also replaced a fuel pump for $6,000. In both cases he had weeks of down time with no income, while waiting for the repairs to be completed.

He said longer wait times at distribution points are also costing him. On this day he had waited six hours for workers at the Blue Buffalo dog food warehouse in McDonough to load his truck. Recently he waited for 15 hours at a Pilgrim’s Pride chicken plant in south Georgia, while he sat with his refrigerated diesel truck running. Garard estimates that with all of his increased expenses this year, his net income will drop from $230,000 in 2021 to less than $100,000 this year.

The challenges that Garard described are now commonplace in the transportation and distribution industries, said Parker, the supply chain expert. “When a system begins to reach its limits of capacity, the wait times become exponential – and costly.”

Why It Matters

Bottlenecks at the ports of Savannah and Brunswick have caused long delays of shipments of all sorts of goods, and disruptions in supply chains across Georgia and elsewhere for well over a year. The “dwell time” of large containers sitting on ships docked at ports, waiting to be loaded onto trailer trucks and delivered to their final destinations, has improved recently with the construction of 20 percent more container and warehouse space this year. The ports are still congested, but cargo fluidity is improving. Dwell times for imported shipments at Georgia ports currently average 9.35 days; six months ago, they averaged 11.38 days, according to the Georgia Ports Authority.

Beyond the ports, at nearshore warehouses and corporate distribution facilities further inland, storage capacity and the skilled labor needed to keep the goods moving is not sufficient to meet pent-up demand that began during the pandemic.

“We’ve been at 95 percent to 98 percent capacity through COVID,” said Parker. “All of the orders were delayed, and then suddenly started coming in, and we didn’t have anywhere to put the stuff.” He said this “bullwhip effect” – when transitory increases in demand cause suppliers and retailers to over-order and push more inventory into the pipeline than future demand can support – accounts for the currently overwhelmed supply chain system, and higher prices for many items.

Ironically, says Parker, the robust and healthy Georgia economy is part of the inflationary trend. Georgia’s near record low 3 percent unemployment rate and continuing revenue growth – income taxes are currently running 10 percent ahead of last year – are perpetuating an economic boom.

“The Atlanta and Georgia economies have outperformed the national economy for over a year, “ he said. “When you’re doing well, and have more jobs than people to fill them, then it’s a double-edged sword. It leads to the kind of shortages and scarcity that then leads to higher prices.”

Competing Economic Prescriptions on the Campaign Trail

Both Gov. Kemp and his Democratic challenger Stacey Abrams are touting their economic plans and prescriptions to curb inflation as a way to appeal to Georgia voters, who cite the cost of living and concerns about the economy as their top issues in recent polls.

When Kemp renewed his two executive orders this month, he said in a statement, “With our nation experiencing 40-year high inflation, ongoing supply chain challenges, and some of the highest gas prices ever, Democrats in D.C. continue to spend taxpayer money with no regard for the costs and its impact on hardworking families … While these politicians continue to double down on bad policies, we are using the means available to us to provide much-needed relief to Georgians. As I've said since we first suspended the fuel tax back in March, we can't fix everything Washington has broken, but we can use the resources we have as a result of our responsible budgeting to keep more money in the pockets of hardworking Georgians."

Kemp plans to return $2 billion of the $6.7 billion fiscal year 2022 surplus to Georgians in the form of state income tax rebates — which would give $250 to single filers and $500 to married couples — and property tax breaks, which would average about $500 per homeowner.

Two weeks ago, Abrams appeared on the ABC talk show "The View" and said, when asked about her fix for inflation, “The goal is not only to bring down prices, but to bring up wages. Georgia is one of the lowest wage states in the nation. And although we have more jobs coming in, those jobs are often low-wage jobs that you have to have two or three of to make a living.”

She promoted her plan to expand Medicaid, which she has said repeatedly on the campaign trail would insure more than 500,000 Georgians currently lacking coverage and create 64,000 new jobs in Georgia. And she pledged to return $1 billion of the 2022 surplus to Georgia taxpayers, “but cap it at those who make $250,000 or less, instead of giving the bulk of money to the wealthiest Georgians.”

What’s Next

“The truth is, there’s no easy way to tame inflation,” said Parker. “There’s always going to be some amount of pain involved. And it’s really at a federal level where you control these levers. States have a limit on what they can do. Giving back a surplus will only help people on a short-term basis.”

In presenting his economic forecast for Georgia and the nation last month, Rajeev Dhawan of the Economic Forecasting Center at Georgia State University said, “Curing inflation will be a year and a half process,” and that a “very determined” Federal Reserve will “eliminate excess demand by hiking interest rates sufficiently.” He predicted that Consumer Price Index inflation rates will average 8.2 percent by the end of 2022, moderate to 4.3 percent in 2023, and settle down to 2.0 percent in 2024.

The pain coming to consumers and employers along the way will manifest in the form of slower job growth and an economic recession, locally and nationally, he said.

“The energy-price-hike-induced inflation has cratered consumer confidence” across the nation, Dhawan said, “signaling less spending in coming months.” He predicts job growth in the U.S. will drop sharply from its 496,000 monthly pace in the first half of 2022 to 165,000 in monthly job losses by mid-2023.

Georgia’s economy, on the other hand, will continue to outperform the U.S. economy, he said, noting that Georgia’s economy is currently buoyed by its low unemployment rate and “superb job growth,” adding 137,400 jobs in the past seven months, led by the hospitality and retail sectors. But “the biggest stumbling block for growth” in those sectors, said Dhawan, will not be rising interest rates, but a shortage of workers to meet the sectors’ “blistering growth rate.” He predicted the robust pace of job growth in Georgia manufacturing (44,000 this year) will also slow, as the increased cost of energy caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues to take its toll.

Overall, he said, the state will gain fewer jobs in 2023 (52,200) than in 2022 (176,200). However, Georgia will still show positive growth, unlike the nation as a whole.

“Labor issues are not getting better any time soon,” said Parker, who agrees that “a shock to the economy” is coming soon in the form of ever-higher interest rates. “The big question is, will it be a soft or a hard landing?”

Join the Conversation

What do you want to know about inflation and the Georgia economy? Share your thoughts by emailing [email protected] or on Twitter @journalistajill.

Follow Key Players for This Story:

Food Costs and Consumer Price Index rates – U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, National Statistics Office of Georgia

Gas Prices – AAA Gas Prices

Martin Parker, Lecturer, Supply Chain Management at University of Georgia, Terry College of Business

Rajeev Dhawan, Chair of Economic Forecasting, Economic Forecasting Center of Georgia State University, Robinson College of Business

***

Header photo: Maurice Garard, an owner-operator long haul truck driver based in McDonough, filling up his truck with gas at the QT truck fueling station in Forest Park this week. (Credit: Jill Jordan Sieder for State Afffairs)

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

‘It is nothing short of insane:’ Bill to criminalize squatting signed by governor

ATLANTA — Today Gov. Brian Kemp signed legislation criminalizing squatting, the illegal practice of entering and residing on someone else’s property without their consent.

The Georgia Squatter Reform Act makes squatting a misdemeanor criminal offense, punishable by up to a year in jail, a $1,000 fine, or both. It also speeds up the timeline to evict a squatter, giving landlords and law enforcement more tools to establish that someone is trespassing and to demand that they leave.

“It is nothing short of insane that there are some who are entering other people’s homes and claiming them as their own,” Kemp said in a post on X after signing the bill at the state Capitol. “Thanks to our legislative partners, I was proud to sign HB 1017 — once again making it clear that illegal squatters are criminals, not residents.”

Over the past few years, squatting has become more prevalent in Georgia, with trespassers breaking into vacant homes, claiming tenancy and refusing to leave.

A 2023 survey of institutional investors in single-family rental homes who are members of the National Rental Home Council found there were 1,200 illegally-occupied homes in and around Atlanta. Realtors told State Affairs they’ve encountered squatters in homes for sale and rent in Gainesville, Valdosta and Albany.

Until now, law enforcement in many jurisdictions treated the issue as a civil matter, telling property owners to file eviction actions in court, which could take months or even years to resolve.

The new law directs local law enforcement to issue citations and arrest people accused of squatting if they don’t provide a valid lease or proof of payment within three days. If they do produce such documents, it moves eviction proceedings to magistrate courts, and requires cases to be heard within seven business days after filing.

If the judge deems documents they present to be forged or fake, those accused of squatting could be charged with a felony. And judges can impose more fines based on the fair market value of rent that landlords lose.

On hand in the governor’s office for the signing was Rep. Devan Seabaugh, R-Marietta, the lead sponsor of the bill.

“Currently in Georgia law, we’re giving squatters tenant rights,” Seabaugh previously told State Affairs. “And my bill would take that away. It basically says, ‘You’re an intruder, you’re a criminal, and we’re going to treat you like a criminal.’ ”

Read these related stories:

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

State troopers are stretched to fight drugs and curb highway deaths

ATLANTA — When Cpl. Anthony Munoz straps on his bullet-proof vest each day and pulls out of the Department of Public Safety headquarters in Atlanta, Munoz never knows how his shift will unfold. What is for certain is that the traffic — of cars, criminals and contraband — is constant.

And what is also true is that there are not nearly enough state troopers on the road to catch them all.

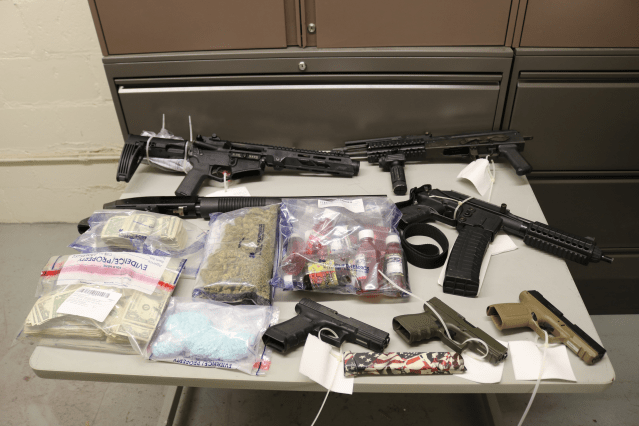

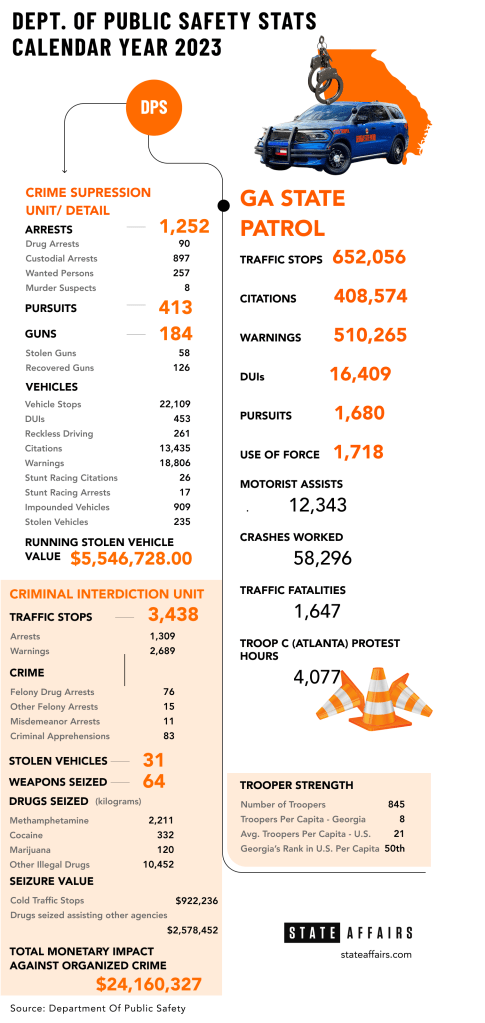

A 13-year veteran, trooper Munoz, 45, is part of the department’s Criminal Interdiction Unit, whose main focus is suppressing the robust illegal drug trade flowing through Georgia. Last year the eight-member team made 1,309 arrests, including 76 felony drug arrests, and helped other agencies seize $24 million worth of contraband.

In 2019, the unit had 25 members.

Capt. Greg Shackleford, the troop commander, said that in 2020 the unit was split up and half the team was sent to Georgia State Patrol posts around the state, which were hurting for staff, to conduct the Department of Public Safety’s core functions — traffic enforcement and responding to car crashes.

The split has translated into Munoz and the rest of his team now spending most of their time monitoring Interstate 20 just south of Atlanta, and Interstate 75/85 west of the city. He said they regularly support the investigations and busts of other local and federal agencies, and frequently join the governor’s crime suppression details, which have included taking down car thieves and street racers.

All this leaves his team with less time to develop intelligence on their own drug cases and to snare more traffickers. It also means the troopers no longer have time to monitor roads in rural areas in south Georgia where, Shackleford said, many drug traffickers driving trailers full of drugs and contraband enter the state on highways coming from Florida and Texas and now ride around unchecked for hundreds of miles.

Chronically understaffed

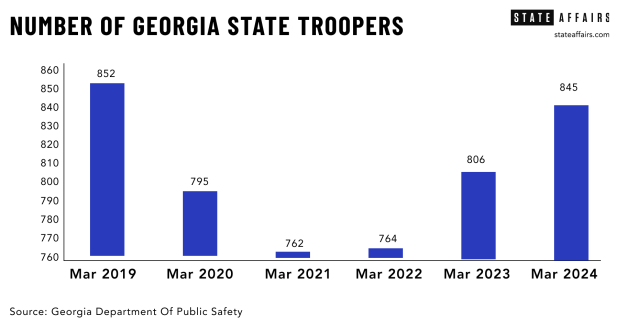

The Georgia State Patrol remains chronically understaffed. While the state’s population has grown, and with it the number of motorists, car crashes and criminal activity, the number of state troopers has hovered stubbornly between about 750 and 850 for over a decade, giving Georgia the unwanted distinction of having lowest number of troopers per capita in the country.

The average number of state troopers per capita in the U.S. is 21; for Georgia, it’s eight. And the outlook for changing that is not great, Col. William “Billy” Hitchens, the public safety commissioner, told legislators during hearings last fall — Unless the state makes bold moves in improving compensation. He said Georgia State Patrol has “aimed to reach 1,000 troopers for as long as I have been employed,” which is 30 years.

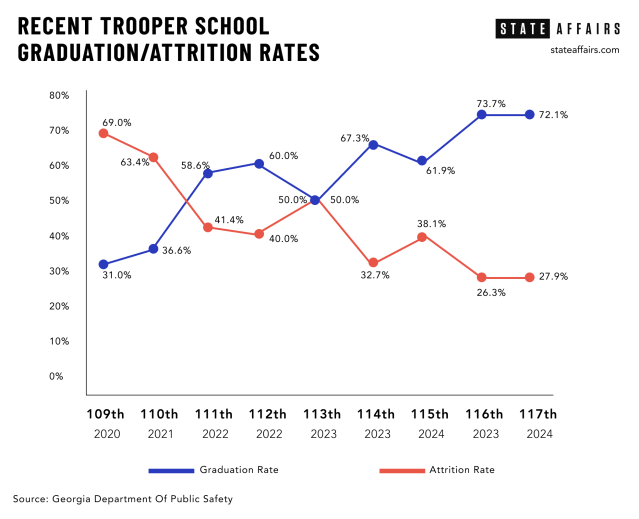

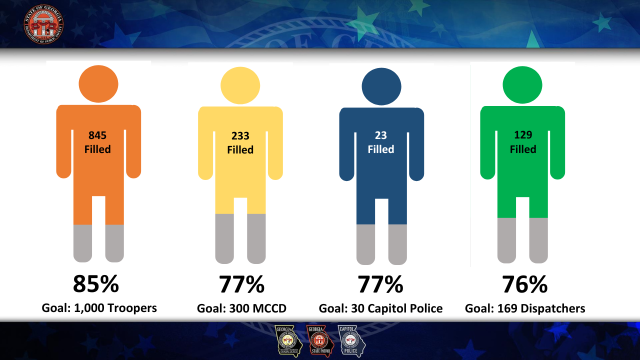

The state saw its trooper numbers plummet to 745 during the pandemic in 2021. The agency is now back to 845 troopers. The current trooper school started with 61 candidates, and if recent history is a guide, about 70% will graduate in September and put on the badge.

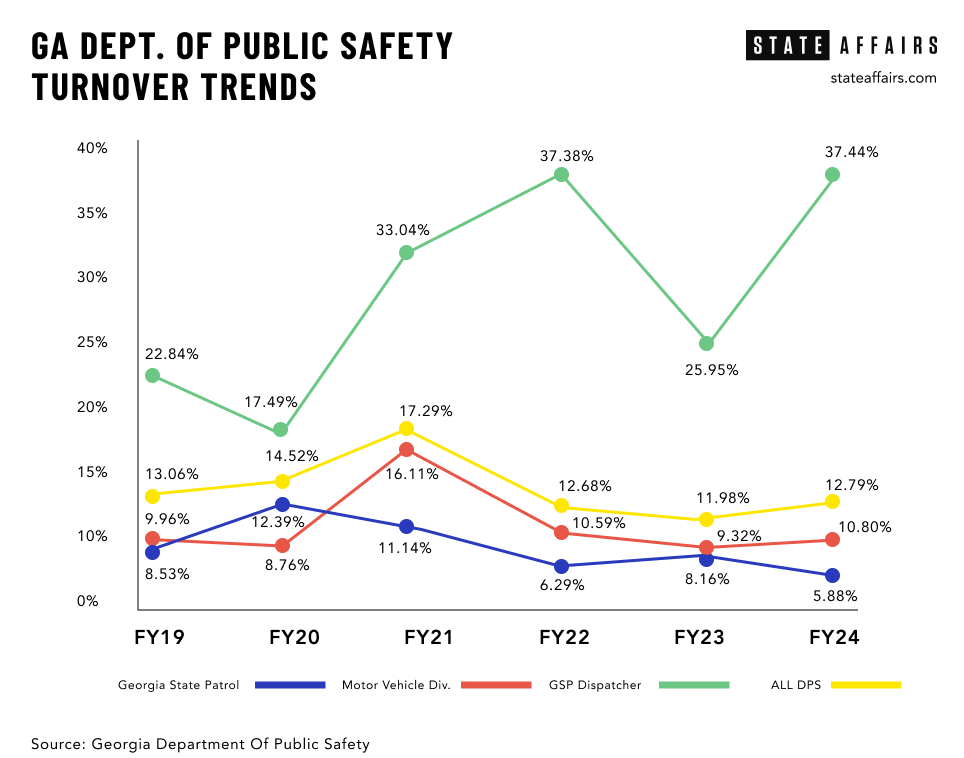

While “things are moving in the right direction” this year in terms of recruitment, said Hitchens, he said too many veteran officers are either resigning or retiring early.

Between 2018 and 2023, 48 troopers left the agency on a full-service retirement, meaning they had served for 30 years. During the same period, 341 troopers resigned, retired early or departed for other reasons. As it costs the department $153,397 to train a trooper, those who left early cost the state $52 million, said Lt. Col. Josh Lamb, director of administrative services for the Department of Public Safety.

Fewer troopers means more highway deaths

Fewer troopers on the state’s roads impact everyone, say law enforcement officials. .

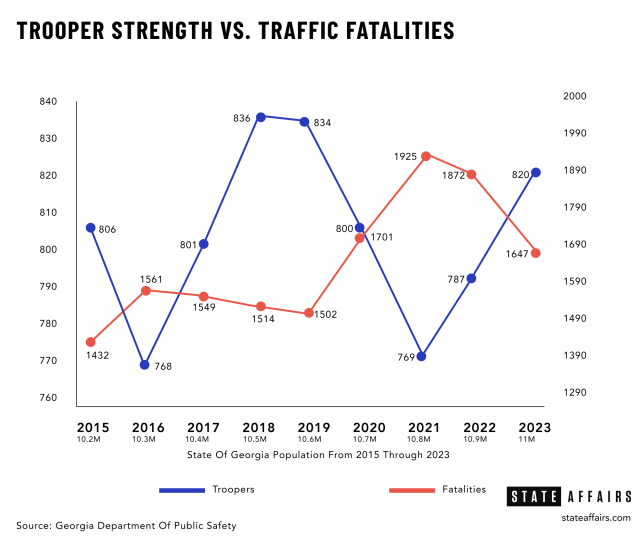

“As our trooper strength decreases, traffic fatalities increase,” said Hitchens.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data shows a direct inverse relationship between trooper staffing and the number of fatalities in Georgia. At its low ebb in 2021, with 769 troopers, 1,925 people died on Georgia roads. More recently, in 2023, with 820 troopers, Georgia saw 1,647 fatalities, an 8% decrease over 2022.

“We are concerned with traffic patterns, the way people drive, and we enforce the law out there,” Hitchens told State Affairs. “When you start losing personnel, whether it’s the state, or cities and counties, one of the first things that may be taken away is traffic enforcement. Because they’re responding to other calls — robberies, domestics, you name it. And when troopers stop doing it, there are just fewer people out there reminding you, ‘Hey, that’s dangerous. Slow down.’ ”

The state patrol wrote 408,574 citations to motorists last year, but issued even more warnings — 510,265. Hitchens noted that mere trooper presence on the highway is a strong deterrent.

“It doesn’t have to be you that gets stopped,” he said. “Those 50 cars that ride by during that time and see that patrol car, go ‘Ooh, I don’t have my seatbelt on … I’m playing with my phone,’ and it just impacts that behavior. But the less officers you see on the road, the less you have people changing their driving behavior.”

Along with encouraging safer driving, DUI enforcement has become a higher priority for the department. A “Nighthawks” squad of 22 officers patrols after midnight in areas of the state where data analysis shows high incidences of alcohol and drug-induced crashes and violations. The state patrol made 16,409 arrests for driving under the influence in 2023.

Hitchens said the work of such special units is compromised when they’re pulled into other duties due to statewide manpower shortages. The three Nighthawks units, for example, are often pulled into other traffic stops and crime suppression details in Atlanta, Macon and Columbus. And drug interdiction officers have had to cover vehicle crashes and multiple public protests over the Atlanta Public Training Center (dubbed “Cop City”) and, more recently, conflict between Israelis and Palestinians in Gaza.

Besides securing troopers, Hitchens said the department is struggling to recruit dispatchers, who are the lifeline for troopers and officers who patrol alone and depend on dispatchers to provide critical information quickly. Today, the department has 129 dispatchers who work at nine regional call centers. They need 169 to be fully staffed.

A tough sell in the ‘Cop City’ era

Hitchens told lawmakers that heightened public criticism of law enforcement over the past few years has played a role in the department’s ongoing challenges to recruit and retain officers.

“People without understanding of what it’s like to be involved in a rapidly evolving life and death situation started scrutinizing officers, cities started defunding their police departments while demanding greater accountability and more training, both of which cost money,” he said. “Following the George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks and Breonna Taylor instances, the media and some leaders in our community nationwide began to demonize the police.”

Hitchens said that since the death of Manuel Teran, a protester against the planned Atlanta Police Training Center who was allegedly shot by a Georgia trooper during a firefight on the forested property in 2023, and the sometimes violent public demonstrations that ensued, “that dynamic just got worse. For a long time with ‘Cop City,’ it was constant protest, and you know, that weighs on you.”

Munoz, who was patrolling with other local law enforcement on the perimeter of the training center site the day Teran died, said the public’s jaundiced view of that episode and other recent struggles between police and citizens that have gone viral on social media can be frustrating.

“I know that a lot of the narrative out there is not true at all,” he said. “There are millions and millions of police encounters every day. And those [violent] ones are fractions of a percent of incidents, and whether a trooper or officer responds the right way, it all boils down to compliance. If you just comply, you’re presumed innocent, you’ll have your chance to make your case, and the facts will come out. Don’t argue, don’t fight, don’t resist. We don’t want to fight you.”

Noting that he has a wife and four children he wants to come home to, Munoz said, “We’ve been pounded with de-escalation in training, and that’s what we practice. I’m sure there are officers out there now that freeze and that say, ‘Do I do my job? Or am I going to be put in prison, because I reacted in a certain way?’ So we do carry that, and it’s a heavy, heavy burden.”

Last year three House Democrats introduced House Bill 107, the Police Accountability Act, which proposes an end to qualified immunity for law enforcement officers and would have required body-worn cameras for all peace officers. The bill did not advance out of committee, but Hitchens said taken together with the public unrest and anti-police sentiment since 2020, it all had a demoralizing effect on his officers.

“All of these factors are forcing officers to become fatigued with our profession,” he said. “They feel that support is ending and the job is not worth the risk.”

According to the Georgia Peace Officers Training and Standards (POST) Council, the number of officers with basic council certifications in Georgia dropped to 5,956 in 2023 from 6,666 in 2017.

“I don’t think there’s a single law enforcement agency in Georgia that is fully staffed,” said Chris Harvey, deputy executive director of Georgia POST. “And they have a very hard time getting qualified people on board. … There just aren’t enough quality people that are interested in doing this job.”

While some agencies have raised salaries and added signing bonuses, he said, “I can tell you that it’s not a solved problem. Because I don’t think it’s primarily a money issue. I think it has a lot to do with the difficulty of doing this job these days. I’m not sure it’s ever been harder to work in law enforcement. The amount of scrutiny along with the amount of violence that police officers encounter on a regular basis, they generally feel like they’re out there alone. If they make one mistake, they’re gonna pay dearly for it. … It’s a tough sell.”

Father and son patrol leaders fight for trooper compensation

For Hitchens, his push to recruit potential state troopers and convince state leaders to increase pay and benefits for troopers is supported by an unlikely suspect — his dad.

House Appropriations public safety subcommittee chair Rep. Bill Hitchens, R- Rincon is a former trooper who served in the Georgia State Patrol for 28 years, and was later appointed by former Gov. Sonny Perdue to serve as public safety commissioner from 2004 to 2011. The elder Hitchens has served in the House since 2013.

At the House Working Group on Public Safety meeting last fall, Rep. Hitchens noted that the state patrol has maintained around 700 troopers since he joined in 1969, when the state population was about 4 million. “Now it’s 11 million people … and we have a lot more murders, stolen cars and merchandise,” the elder Hitchens said. “Where we fell down, I don’t know. It’s just we’ve never grown. … And now we’re at a breaking point.”

The younger Hitchens was appointed by Gov. Brian Kemp as deputy commissioner for public safety in 2020, and then as commissioner in 2023. As commissioner he oversees the Georgia State Patrol, the Motor Carrier Compliance Division, the Capitol Police Division, and other special law enforcement units, including the crime suppression, SWAT and canine teams.

The son and father team have successfully fought for substantial pay raises for troopers, whose salaries have increased over the past three legislative cycles by nearly $17,000. That includes a 4% cost of living increase and a $3,000 bonus for law enforcement officers approved by the General Assembly in the fiscal year 2025 budget. The starting salary for a new trooper will be $63,684 as of July 1, if the governor approves it in the budget, as expected.

Dispatchers will also get a boost in next year’s budget, with new pay step increases that can take them from a starting salary of $39,000 to up to $56,000 as they earn promotions.

Col. Hitchens said those pay bumps seem to be turning the tide on recruitment. The number of applicants and graduates rose for the last few trooper schools held over the past year. Other changes the department made to trooper school requirements have also helped, including allowing people to go home more often during training, permitting access to mobile phones at night, and allowing people with arm tattoos to train and serve, if they cover them with long sleeves.

“We tried to make changes in training that we felt like really didn’t help people stay,” said Hitchens. “And we didn’t make it kinder or gentler. I mean, in this job that you sign up for, there’s got to be a certain level of discipline, there’s got to be a certain level of respect, with high physical training standards, that’s still there. But the things that we could change, we decided to do.”

Both men remain concerned about how to stem the trend of early retirement, and agree that sweetening the retirement package is the key way to combat it.

Currently most troopers qualify for a pension equal to 1% of their final pay for every year of service, and can also participate in a 401(K) savings plan while they serve, which the state matches up to 9%, depending on their number of years on the force. But Col. Hitchens is pushing for a more generous “defined benefit” retirement plan, with a 3% pension, which he said would double what most troopers get when they retire. Instead of earning about $25,000 a year on average, they would receive about $52,000.

Presently, the average tenure of a state trooper is 10 years, nowhere close to the 30-year careers Hitchens and other leaders want his officers to pursue.

And he knows it matters to them, as retirement benefits emerged as the number one retention issue on a recent agency-wide, anonymous survey.

“Every other agency is increasing their hiring packages, raising pay and offering better benefits, from retirement to free health care,” Hitchens said, noting that the Atlanta and Sandy Springs police departments offer substantially higher pay and 3% defined benefit plans.

“We’re in a competitive bidding process, and we have to offer a reward that’s worth the risk our people are taking with their lives and liberty.”

The tenure of senior officers also matters because of the crucial role they play in mentoring new recruits.

“When we have our young troopers, the men and women that come into the field, they’re excited,” said Shackleford, the troop commander, who spent much of his 36-year public safety career in SWAT before taking over Troop K, which includes the crime suppression, criminal interdiction, K-9, SWAT and dive units. “They see the fast cars, they want to get into something. And the problem is, it’s just like a puppy. A puppy’s gonna get into something and make a mess. So we need the older ones to kind of calm them down and guide them a bit, show them how to see and assess a situation.”

Such role modeling of behavior, said Hitchens, “is very important, especially with de-escalation. A senior officer, having dealt with so much of that, has that confidence and the competence to carry out [their] job in a way that I think a lot of younger, less experienced officers don’t have yet. And that’s how you learn and morph over a career,” said Hitchens, adding that that transfer of knowledge and practice from veterans to recruits “benefits the public as well.”

Rep. Hitchens co-sponsored two bills related to bolstering retirement plans for law enforcement that passed out of the retirement committee during the last session. One passed in the House, but did not get a vote in the Senate. Other lawmakers balked at the cost.

Read these related stories:

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

In hot water with your HOA? A new law buys you time to fix the problem

The Gist

Georgia homeowners living in communities governed by homeowners’ associations now get time to fix a covenant violation before the HOA can take legal action, thanks to legislation signed into law Monday.

Gov. Brian Kemp signed House Bill 220 at the Capitol, continuing his flurry of bill-signings across the state. To date, Kemp has signed about three dozen bills since sine die, which marked the end of the 2024 legislative session, his spokesman Garrison Douglas told State Affairs. Sine die ended in the early hours of March 29. The governor has until May 7 to sign, veto or take no action on a bill. If he takes no action, the bill automatically becomes law.

What’s Happening

HB 220 requires community-governed associations to notify in writing a home or condo owner of a covenant breach — such as painting their house a color not approved by the association, and give them time to fix it before going to court or taking some other legal action.

Rep. Rob Leverett, R-Elberton, sponsored the bill which included parts of an HOA bill promoted by Sen. Donzella James, D-Atlanta. James had been trying for two years to get some HOA-related legislation passed.

While the HOA portion of HB 220 does not go as far as James’ proposed single legislation, it’s a start, she and others say.

Why It Matters

An overwhelming majority of new subdivisions being built in Georgia now will have HOAs, experts told State Affairs. In fact, new homes that are part of a homeowner association are growing fastest in the southern and western part of the United States. An estimated 2.2 million, roughly 22%, Georgia residents live in a building or home overseen by anHOA or some other type of community association, according to the Community Association Institute.

Lawmakers such as James have heard complaints in which HOAs have terrorized homeowners and threatened to take their property, all while homeowners have had little to no legal options. In some cases, homeowners have lost their homes after falling behind on HOAs fees, even if they never missed a mortgage payment.

What’s Next?

While HB 220 is now law, Senate Resolution 37 has yet to be appointed. The resolution, sponsored by James, creates the Senate Property Owners’ Associations, Homeowners’ Associations, and Condominium Associations Study Committee. Committee members will be appointed by the President of the Senate, Lt. Gov. Burt Jones.

Lawmakers appointed to the committee will delve further into HOA issues before presenting recommendations to the Legislature when it convenes in January.

See related stories:

Have questions? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss any election news you need to know.

X @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

All you need to know heading into the May 21 primary

Gist

Georgia’s primary is less than a month away and there’s a lot to unpack.

The May 21 primary will be the first time some Georgians will be voting in new districts for state and congressional candidates. They’ll also be voting in local races for sheriff, judges, school board or county commission members. Primary winners who have challengers will go on to compete in the Nov. 5 general election. Georgia is an open primary state, meaning voters can choose the party ballot they wish to vote for.

This year, Georgians who want to vote absentee in the primary could face possible challenges due to mail delivery delays.

What’s Happening

North Georgia and metro Atlanta are seeing significant mail delivery delays. The holdup, according to media reports, appears to be at the United States Postal Services’ new Regional Processing and Distribution Center in Palmetto. The problem has led to dangerous situations in which people are not getting critical medication.

Georgia’s U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff recently grilled USPS Postmaster General Louis DeJoy on the delays. Ossoff told DeJoy during an April 16 hearing that on-time delivery rates were abysmal. He said 66% of outbound first-class mail had been delivered on time while 36% of inbound mail had been delivered on time in the last three months.

DeJoy blamed the problem on the difficulty in condensing operations at the facility.

With the approaching primary, state lawmakers are concerned the ongoing mail delays could disrupt the election process.

Mike Hassinger, a spokesman for the Secretary of State’s office, told State Affairs that Georgia voters are ready.

“Georgia voters are already registered,” he said. “They know how they like to vote. More than half of them vote early. About 5% vote absentee by mail, just in general, and then the rest are voting on election day. So we’ve been able to set up systems that are familiar with Georgia voters so that the percentage who might be worried about their absentee by mail ballots are relatively small.”

Why It Matters

Georgia emerged as one of the country’s most important political battleground states during the 2020 election. The Peach State will once again play a key role in deciding who wins the 2024 presidential election in November.

In the May 21 primary, Georgia voters will whittle down their choices for who they send to Congress and to the state capitol next year.

Under a federal court-approved redistricting process last year, Georgia now has new congressional and state district electoral maps. Those maps created one majority Black seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, five new majority-Black districts in the state House and two in the state Senate.

The redistricting resulted in new seats, intriguing matchups and former politicians returning to the fray. You can see the newly drawn maps here.

What’s Next?

Here’s what you need to know to ensure a smooth voting process:

To vote early.

Early voting is April 29 to May 17. Find your polling place here.

To vote absentee.

Here’s what you can do to avoid problems if you vote absentee:

- Get your absentee ballot application done early. You can request an absentee ballot here.

- Track your application through Georgia BallotTrax. You must have a valid absentee request on file with your county board of elections in order to see your absentee ballot status in Georgia BallottTrax.

- If you’ve been having mail delays, place your completed absentee ballot in an official drop box during advanced voting instead of using the United States Postal Service. Check your county voter registration and election office for drop box locations. And yes, your absentee ballot counts. It is counted in the final tally not just close races.

- If you change your mind about voting absentee and decide to vote in person, take your absentee ballot to your local elections office where they will void it.

- If you need to contact your county election office, find that information here.

Have questions, comments or tips? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss any news you need to know.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram@StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs