Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoHow two Augusta schools sit on different ends of Georgia’s Climate Star Rating system

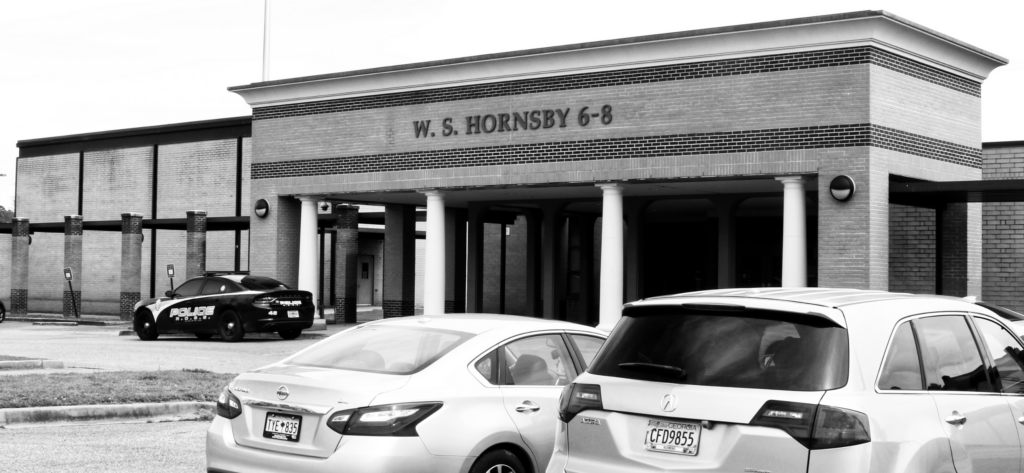

W.S. Hornsby Elementary School in Augusta, Georgia, serves 642 students in grades kindergarten through fifth. (Credit: Michael Johnson)

In part two of this two-part series on the state of Georgia’s School Climate Star Rating system, designed to measure a school’s environment for learning and thriving, State Affairs senior investigative reporter Tammy Joyner looks at two schools in Augusta that sit right next to each other but were rated the best and worst in the School Climate Star Rating system. Read part one here.

AUGUSTA, Ga. — W.S. Hornsby Middle School recently hosted a “Books and Burgers” night, hoping to draw parents to the school. Less than two dozen came.

“We sent out flyers. We told the children, ‘Hey, [tell] your parents come to get free books. You get free hamburgers and chips. You have dinner for the night,’” Principal Stacey King told State Affairs. “Still 20 parents. What do you do?” Hornsby has nearly 400 students in grades six to eight.

Hornsby Middle School and W.S. Hornsby Elementary School are situated in one of Augusta’s toughest communities: East Augusta. Neither school has a Parent-Teacher Association.

East Augusta is a collection of mostly single-parent, working-poor households. Both schools have had their share of change. Initially, both schools started in 2007 as one school for kindergarten through eighth grade. It later split into two schools: K-3 and 4-8, which served as the middle school. The two schools became traditional elementary (K-5) and middle schools (6-8) after the last climate rating was done in 2019.

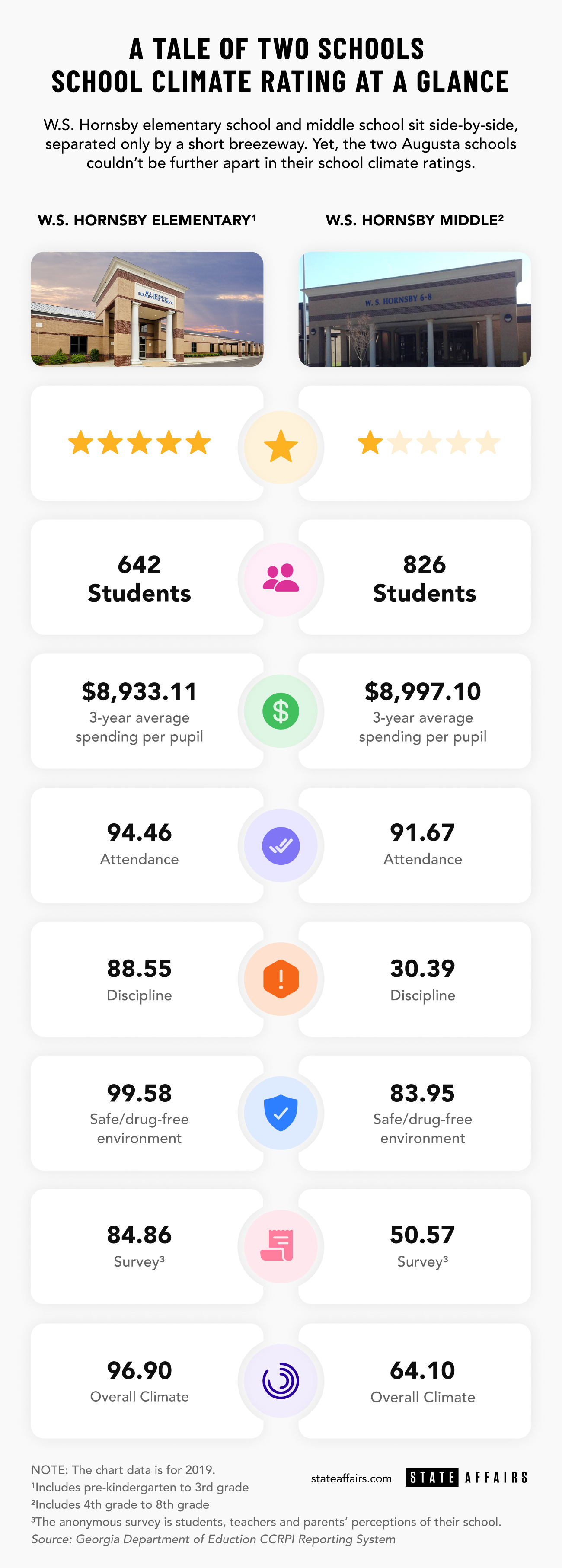

The middle school is among five of Augusta’s Richmond County schools that received one star on the state’s School Climate Star Rating metrics in 2019, the latest data available. Two of the five schools no longer exist while two others are under new leadership, including Hornsby Middle School. (Hornsby Elementary School received five stars.)

The five-star system

While the School Climate Star Rating system is not a measure of academic achievement, it does provide a glimpse into whether a school is a good, safe environment for learning.

Following nearly three years of a pandemic that kept children from a structured learning environment, the answer to whether the Department of Education will continue the rating system, which was halted in 2020 when COVID-19 hit, is unclear.

“We are currently evaluating when the star rating can be reinstated to ensure valid and reliable data,” Meghan Frick, a spokesman for the state Department of Education (DOE), told State Affairs in an email.

DOE officials may be considering revising parts of the system, according to several people familiar with it.

Georgia’s statewide School Climate Star Rating program is the result of a decades-old effort to cut the number of bullying incidents and out-of-school suspensions. The rating system is calculated using data from the Georgia Student Health Survey, Georgia School Personnel Survey, Georgia Parent Survey, student discipline data and attendance records for students, teachers, staff and administrators.

“When you walk in the building, it’s that warm feeling you get. It encourages kids to come to school, and it provides the metrics for school systems to use to improve,” said Caitlin Dooley, who oversaw the School Climate Star Rating program from 2020-2022. “It’s a foundation for learning, going to a school that is a comforting place, a school where people greet you at the door and talk to you while you’re there. A school where you feel like you’re safe, and you have a sense of belonging and you feel like you have a friend. Those are places where you would have the cognitive capacity to learn,” said Dooley, who noted that the program cost between $2 million and $3 million a year to administer statewide. The costs, she said, were largely for personnel.

The tale of two schools

This year marks Principal King’s first year as the head of W.S. Hornsby Middle School. She’s working with the elementary school next door to co-host more school activities since many families have kids at both the elementary and middle schools.

King is aware of her middle school’s 1-star climate rating and some of the factors that have resulted in the low score.

“We are working on our school climate score. I think our school climate score is a combination of maybe some mishaps just like in the community as a whole,” she said during a sitdown conversation in a conference room at the school.

Just getting students to show up for school has been one of the middle school’s biggest post-COVID challenges.

“A lot of times … what gets us [is] attendance. Our students sometimes are out of school for a while, depending on what’s happening at home,” King said. “That’s something we can’t really control here in school. You can do all the calling, ‘Hey, mom bring them [to school],’ but when mom needs them to babysit or whatever, then they’re home,” she added.

According to the Georgia Department of Education, “Data indicate that missing more than five days of school each year, regardless of the cause, begins to impact student academic performance and starts shaping attitudes about school.”

King insists there’s healthy teacher-student interaction at the school.

“When they’re in class or even during the day when they’re walking from here to there, they’re quiet. They’re very mannerable. They know we care about them but they also know the ones who come in who might not care so much about them,” she said. “We do a lot of counseling and mental health work. We talk to them all the time.”

Frank Scott said he’s not surprised the middle school got low marks on school climate rating. Scott, a married military vet with a year-old son, is raising his nephew DeMarquez Dukes, a sixth grader at Hornsby Middle.

“That’s basically because of where the school is located here in Richmond County,” the Augusta resident said. “I went to Lakeside [High School] in Columbia County. I’ve never been to an Augusta school. Over here is very different from what they teach in Columbia County. So having a kid in this school system is an eye-opener. It’s very different from when I was going to school.

“If it wasn’t for the kids, it would be a great atmosphere,” Scott said. “The teachers do their best. Some of them go above and beyond for the students. [Although] I had one [teacher] tell me that she has a lot of kids and she just can’t focus on one.”

Dukes, 13, said he likes school in general, especially math because the “teacher sits down and breaks it down for us,” but he “hates the bullying.” He said he is constantly being provoked into fighting other students at the school.

More than 56,000 fights were reported in schools across Georgia during the 2021-22 school year, according to the Georgia Department of Education. Bullying has become such a problem that the state has moved to make bullying a misdemeanor crime.

Dukes said he recently got two days of in-school suspension after a boy pushed him and he pushed him back. Not a school day goes by, the 13-year-old said, where he’s not seen students fighting or talking back to teachers. Despite the “drama,” he said he feels safe and supported in school.

The gold standard

Next door at W.S. Hornsby Elementary School, principal Gregory Shields Jr. reflects on his school’s 5-star rating.

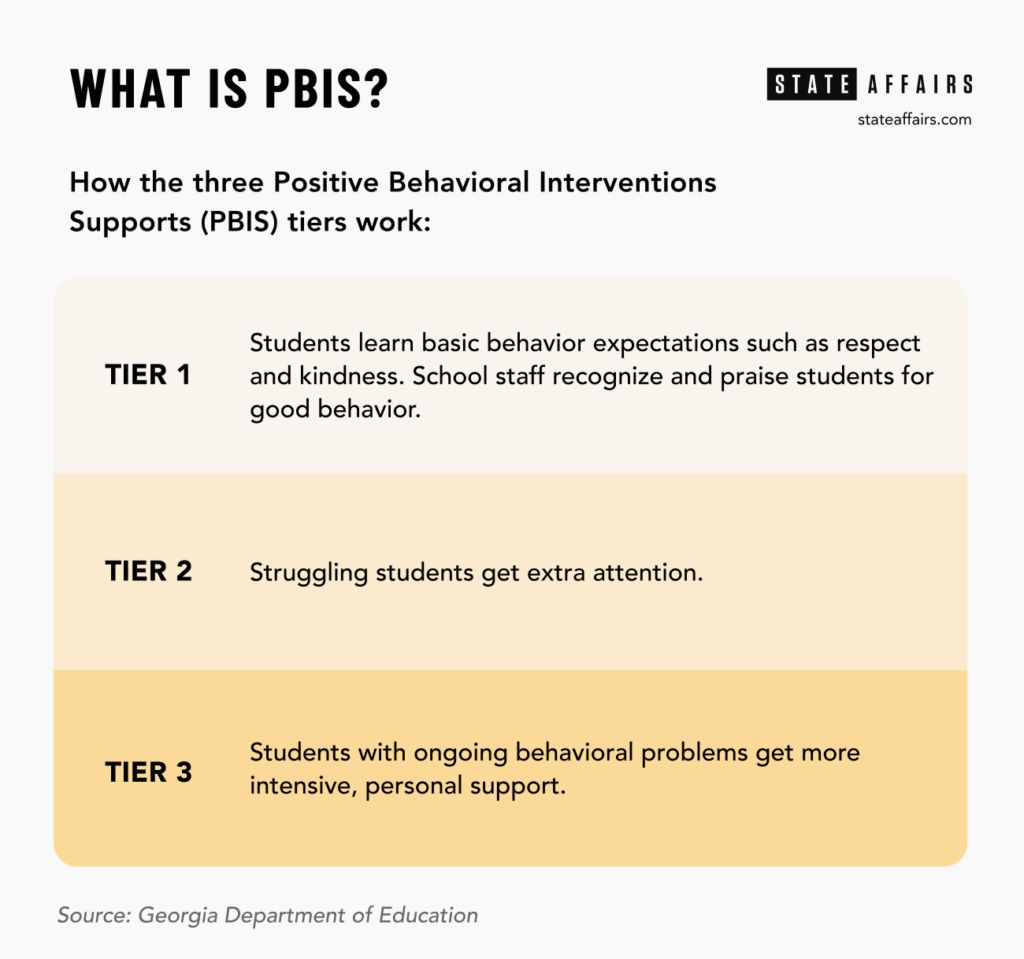

“I wasn’t here but what I’ve noticed is one thing: behavior,” said Shields, who is in his second year as principal. “We have a great PBIS program here.”

Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS) focuses on praising rather than punishing students and redirecting, when possible, a student’s behavior to get a better outcome. It has been known to improve academic performance and perceptions of schools, education experts say. It also has reduced suspensions, anti-social and aggressive behavior, bullying, drug use and teacher turnover, according to the Center on PBIS.

At the elementary school, students participate in after-school events. Those with perfect attendance or positive behavior are regularly singled out for recognition.

“The more they are involved and recognized, it encourages them to come to school,” Shields said. “I know for sure that was definitely a positive factor in regards to school climate.”

Creating a good learning environment “takes a lot of work,” Shields said. “When our parents see that the teachers care, we do very well. We’re intentional with the support we provide our students as it relates to their health. I tell our teachers and staff all the time, ‘This is their safe place.’”

When the students are not in school, Shields said he is aware of the turmoil many of them are exposed to in the surrounding communities or in their homes.

“So when they come here, we want this to be a structured and stable environment for them.,so that when they come, they will get a good meal,” Shields said. “When they come, they will be spoken to in a manner that we want them to be raised up to speak to others. They get the opportunity to speak out and to be heard and express their feelings and things of that nature.”

The elementary school has two counselors who Shields said regularly visit classrooms and provide guidance. “They are well-versed. They’ve discussed topics like bullying and different things like that. So that helps tremendously.”

Home of the Masters, and the poor

Hornsby elementary and middle schools are about a mile from historic downtown Augusta where a statue of native son and “Godfather of Soul” James Brown is prominently featured.

Aside from being Brown’s hometown, Georgia’s third-largest city is the azalea-draped home to the prestigious Masters Golf Tournament during the first week of April when this city of over 200,000 doubles in population.

Throngs of golf fans flood the town known for its azaleas and large southern homes with grand porches. The tournament, along with a slew of festivals and the city’s picturesque River Walk, draw tens of thousands to the city each year.

Beyond the pageantry, Augusta is a place that’s been struggling to right itself for over a quarter of a century, some longtime residents say.

“Augusta seems like it never reaches its potential. We have lost our luster over the years,” Janice Allen Jackson, former city manager of Albany and former administrator of the consolidated Augusta government, said recently over lunch at Augustino’s Grill in downtown Augusta.

Born and raised in Augusta, Allen Jackson is now a consultant and host of the podcast “Local Matters.” She recently produced a multi-part series, “Are Schools Failing Our Kids? Or Are Our Kids Failing Schools?

Like many communities in Georgia and across the country, Richmond County has experienced its own version of white flight, a phenomenon that began shortly after Augusta and Richmond County consolidated its governments under a federally-approved plan in 1996.

Allen Jackson remembers people leaving the county for nearby Columbia County, a more affluent, mostly white county where the population has exploded. Others put their children in private schools or they home-school. Meanwhile, Augusta-Richmond County’s population has limped along, adding only 16,000 residents in the last 25 years.

Today, nearly 6 in 10 Richmond County residents are Black. It’s a mix of white- and blue-collar jobs: sales and office workers, service providers and professionals. Many residents work in the medical field, manufacturing plants or at the nearby Fort Gordon Army Base. Slightly more than a third — 34% — of the families in the county live below the poverty level. Half of the homes in the county are headed by women. The median household income of parents with kids in public schools is $41,903.

Three in 4 students who attend Richmond County public schools are Black.

In the last decade, the school district has spent more than $300 million building and renovating schools. More recently, the district has begun closing or consolidating schools, including Southside Elementary, another school that got a 1-star climate rating in 2019, the latest data available. It was closed because it was underused, school officials said.

Students in 54 of the district’s 57 schools are eligible for free or reduced lunch. For a family of four, that means earning $55,500 before taxes.

‘We need to do work’

Like many school districts, Richmond is experiencing teacher shortages.

Since the pandemic, job openings for teachers in Richmond County have grown more than 50%. The need was so great at the beginning of this school year that 1 in 5 teachers hired by Richmond County schools got their jobs through emergency or provisional waivers, one local TV station reported.

The district currently has 300 teacher openings.

Richmond County School Superintendent Kenneth Bradshaw called the 2019 school climate rating data for his district a “broad stroke.”

“I looked at not only the five schools [that got a 1-star rating] but we also had five schools that obtained a five-star rating,” Bradshaw said. “The five schools that obtain the lower ratings means we need to do work. We need to focus on it. We need to target those schools and provide the support that’s needed based on that being an indicator.”

Bradshaw said the 32,275-student district has begun focusing on PBIS.

“It really tries to capture what’s happening in the building,” Bradshaw said. “We believe that when our administrators, teachers and students become more familiar with this program, it’s aligned with our code of conduct and it gets our parents and teachers involved. It will work for our school system.”

Bradshaw believes the PBIS program is a gateway to creating better relationships between students and teachers.

“The PBIS program gives us direction on how we can get to better know our students, and then begin to teach them,” he said. “Many of them come from different and various environments. It’s helpful to get to know who they are.”

As for the state’s School Star Climate Rating system?

“I’m fine with it,” Bradshaw said. “I always believe in metrics for accountability. In general, I like having some sort of metric because you always want to establish your baseline.”

Bradshaw said he “couldn’t say 100%” whether the 2019 data accurately reflected the district. “A lot of this information is based on how our students feel as they take the survey. So there are a lot of intangibles,“ he said. “But I would say that it’s an indicator.”

US education system falls behind

Richmond County School Board member Wayne Frazier said the American education system hasn’t kept pace with societal changes and challenges.

Richmond schools are not educational outliers. Students and schools throughout Georgia and the nation are increasingly under siege with school shootings and higher cases of mental health, among other issues.

Educators are overwhelmed, stretched beyond their capacity and leaving the district, say school officials. Parents are work-stressed. Some students live in communities where it’s not unusual to find bodies behind school buildings or children having to duck bullets when they’re at home. Kids are acting out, bullying each other and picking fights at school, Frazier added.

“We’re behind. We’re not keeping up with the culture of the communities,” Frazier told State Affairs. “We’re teaching these children as if they’re coming in the school doors ready to learn.

“The teachers are not social workers. They are not trained at that level. They shouldn’t be trained to handle this kind of stuff that comes in a classroom. So these situations play out in the classroom with misbehavior and everything else. Not interested in work. Not interested in school. The teachers and the staff are not prepared to address these types of issues when these issues are dominating the schools.

“We need more wraparound and psychological help for these children to get them prepared to learn. This is a major problem we’re having in the school that’s causing the [low ratings in school] climate. These types of problems are really what’s overwhelming the education environment right now and we’re not prepared to handle it.”

Churches like Greater Young Zion Baptist, which sits across from the two Hornsby schools, have stepped in to fill those needs with mentoring and meals.

“These kids really see a lot of things that kids should not be seeing,” said Rev. William B. Blount Sr. “We started a mentoring program. We’re taking a lot of these kids in and trying to teach them how to dress and teach them how to conduct themselves properly. We have a curriculum-based program with the kids. Number one, ‘you got to obey your parents.’”

Crime and violence has declined in the area since a major housing project was eliminated about six years ago, Blount said. “It’s much quieter now.”

Meanwhile, school board member Frazier said rating school environments is fine if state officials plan to address the inequities found in the data.

“I don’t see anything that we’re doing to close the gaps, other than punishing teachers and punishing the system,” he said. “We’ve got some of the most up-to-date, technologically-advanced schools in the world. But what good is that if you’ve got broken children in the schools and [they] can’t learn?”

Want to see how your individual school or school district performed on the last School Climate Star Rating? Find out here.

You can reach Tammy Joyner on Twitter @lvjoyner or at [email protected]. Joyner is State Affairs’ senior investigative reporter in Georgia. A Georgia transplant, she has lived in the Peach State for nearly 30 years.

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Know the most important news affecting Georgia

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

Unlimited Access: Subscribe for just $2.99/mo billed monthly.

Subscribe NowGet unlimited news access

Already a member? Login here

‘It is nothing short of insane:’ Bill to criminalize squatting signed by governor

ATLANTA — Today Gov. Brian Kemp signed legislation criminalizing squatting, the illegal practice of entering and residing on someone else’s property without their consent. The Georgia Squatter Reform Act makes squatting a misdemeanor criminal offense, punishable by up to a year in jail, a $1,000 fine, or both. It also speeds up the timeline to …

State troopers are stretched to fight drugs and curb highway deaths

ATLANTA — When Cpl. Anthony Munoz straps on his bullet-proof vest each day and pulls out of the Department of Public Safety headquarters in Atlanta, Munoz never knows how his shift will unfold. What is for certain is that the traffic — of cars, criminals and contraband — is constant. And what is also true …

In hot water with your HOA? A new law buys you time to fix the problem

The Gist

Georgia homeowners living in communities governed by homeowners’ associations now get time to fix a covenant violation before the HOA can take legal action, thanks to legislation signed into law Monday.

Gov. Brian Kemp signed House Bill 220 at the Capitol, continuing his flurry of bill-signings across the state. To date, Kemp has signed about three dozen bills since sine die, which marked the end of the 2024 legislative session, his spokesman Garrison Douglas told State Affairs. Sine die ended in the early hours of March 29. The governor has until May 7 to sign, veto or take no action on a bill. If he takes no action, the bill automatically becomes law.

What’s Happening

HB 220 requires community-governed associations to notify in writing a home or condo owner of a covenant breach — such as painting their house a color not approved by the association, and give them time to fix it before going to court or taking some other legal action.

Rep. Rob Leverett, R-Elberton, sponsored the bill which included parts of an HOA bill promoted by Sen. Donzella James, D-Atlanta. James had been trying for two years to get some HOA-related legislation passed.

While the HOA portion of HB 220 does not go as far as James’ proposed single legislation, it’s a start, she and others say.

Why It Matters

An overwhelming majority of new subdivisions being built in Georgia now will have HOAs, experts told State Affairs. In fact, new homes that are part of a homeowner association are growing fastest in the southern and western part of the United States. An estimated 2.2 million, roughly 22%, Georgia residents live in a building or home overseen by anHOA or some other type of community association, according to the Community Association Institute.

Lawmakers such as James have heard complaints in which HOAs have terrorized homeowners and threatened to take their property, all while homeowners have had little to no legal options. In some cases, homeowners have lost their homes after falling behind on HOAs fees, even if they never missed a mortgage payment.

What’s Next?

While HB 220 is now law, Senate Resolution 37 has yet to be appointed. The resolution, sponsored by James, creates the Senate Property Owners’ Associations, Homeowners’ Associations, and Condominium Associations Study Committee. Committee members will be appointed by the President of the Senate, Lt. Gov. Burt Jones.

Lawmakers appointed to the committee will delve further into HOA issues before presenting recommendations to the Legislature when it convenes in January.

See related stories:

Have questions? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss any election news you need to know.

X @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

All you need to know heading into the May 21 primary

Gist

Georgia’s primary is less than a month away and there’s a lot to unpack.

The May 21 primary will be the first time some Georgians will be voting in new districts for state and congressional candidates. They’ll also be voting in local races for sheriff, judges, school board or county commission members. Primary winners who have challengers will go on to compete in the Nov. 5 general election. Georgia is an open primary state, meaning voters can choose the party ballot they wish to vote for.

This year, Georgians who want to vote absentee in the primary could face possible challenges due to mail delivery delays.

What’s Happening

North Georgia and metro Atlanta are seeing significant mail delivery delays. The holdup, according to media reports, appears to be at the United States Postal Services’ new Regional Processing and Distribution Center in Palmetto. The problem has led to dangerous situations in which people are not getting critical medication.

Georgia’s U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff recently grilled USPS Postmaster General Louis DeJoy on the delays. Ossoff told DeJoy during an April 16 hearing that on-time delivery rates were abysmal. He said 66% of outbound first-class mail had been delivered on time while 36% of inbound mail had been delivered on time in the last three months.

DeJoy blamed the problem on the difficulty in condensing operations at the facility.

With the approaching primary, state lawmakers are concerned the ongoing mail delays could disrupt the election process.

Mike Hassinger, a spokesman for the Secretary of State’s office, told State Affairs that Georgia voters are ready.

“Georgia voters are already registered,” he said. “They know how they like to vote. More than half of them vote early. About 5% vote absentee by mail, just in general, and then the rest are voting on election day. So we’ve been able to set up systems that are familiar with Georgia voters so that the percentage who might be worried about their absentee by mail ballots are relatively small.”

Why It Matters

Georgia emerged as one of the country’s most important political battleground states during the 2020 election. The Peach State will once again play a key role in deciding who wins the 2024 presidential election in November.

In the May 21 primary, Georgia voters will whittle down their choices for who they send to Congress and to the state capitol next year.

Under a federal court-approved redistricting process last year, Georgia now has new congressional and state district electoral maps. Those maps created one majority Black seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, five new majority-Black districts in the state House and two in the state Senate.

The redistricting resulted in new seats, intriguing matchups and former politicians returning to the fray. You can see the newly drawn maps here.

What’s Next?

Here’s what you need to know to ensure a smooth voting process:

To vote early.

Early voting is April 29 to May 17. Find your polling place here.

To vote absentee.

Here’s what you can do to avoid problems if you vote absentee:

- Get your absentee ballot application done early. You can request an absentee ballot here.

- Track your application through Georgia BallotTrax. You must have a valid absentee request on file with your county board of elections in order to see your absentee ballot status in Georgia BallottTrax.

- If you’ve been having mail delays, place your completed absentee ballot in an official drop box during advanced voting instead of using the United States Postal Service. Check your county voter registration and election office for drop box locations. And yes, your absentee ballot counts. It is counted in the final tally not just close races.

- If you change your mind about voting absentee and decide to vote in person, take your absentee ballot to your local elections office where they will void it.

- If you need to contact your county election office, find that information here.

Have questions, comments or tips? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss any news you need to know.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram@StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs