Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoThe Gist

Flush with billions in cash and a AAA bond rating, Georgia faces a pivotal moment in its fiscal future.

For more than a quarter of a century, Georgia has maintained an enviable reputation when it comes to managing its money. That’s how long the Peach State has had a AAA-bond rating from the U.S.’s top three credit-rating agencies. In layman’s terms, that’s like having an 850 credit score that gets you the best interest rate when buying a car or home. Similarly, the state of Georgia gets the best rates when borrowing money or issuing bonds to build things like roads, prisons, or buildings on a college campus.

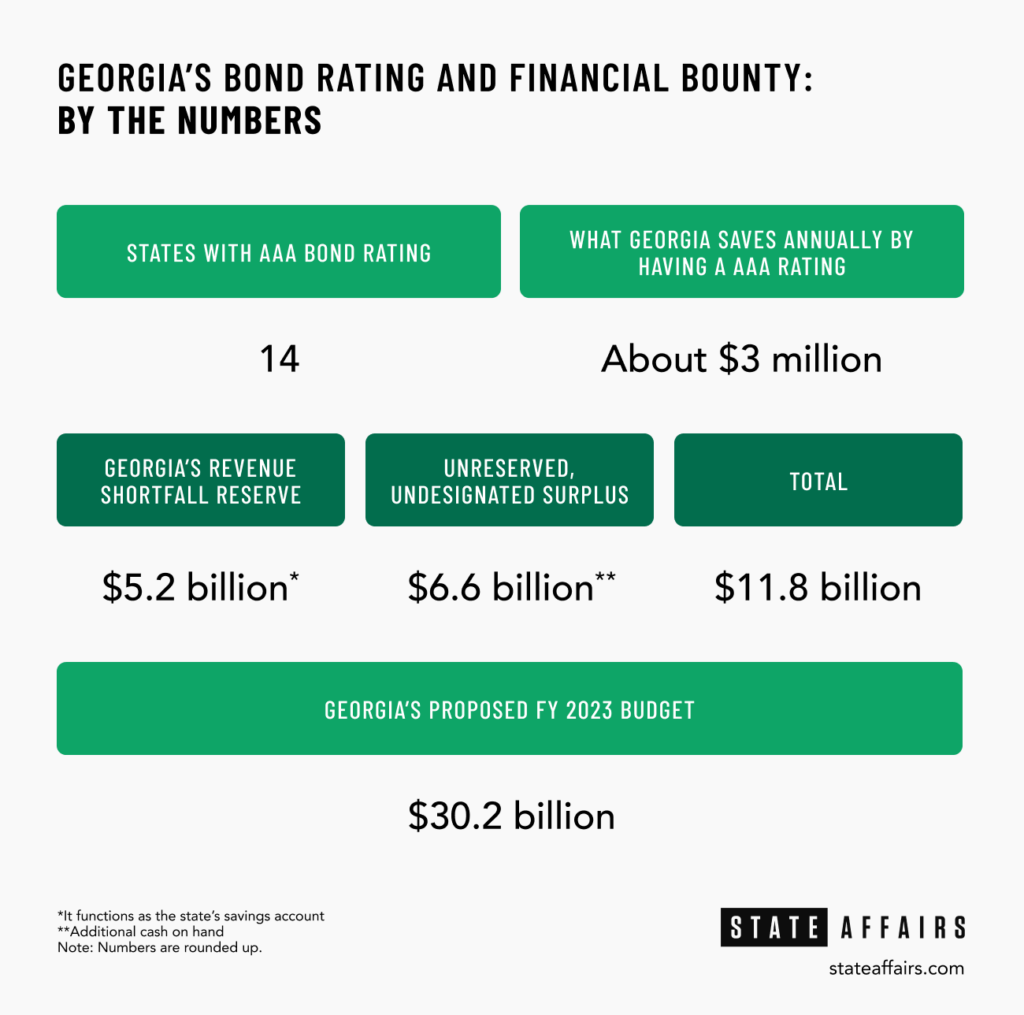

Currently, only 14 states belong to the AAA bond rating club.

“The fact [that] we have maintained these coveted ratings for so long is a testament to our conservative approach to budgeting and governance, our pro-business policies, and especially the hardworking Georgians who make up our robust workforce,” said Gov. Brian Kemp, adding, “Job creators will continue to bring opportunities to the Peach State because they, like the rating agencies, know we are a safe bet.”

That safe bet is buoyed by nearly $12 billion sitting in state coffers — $5.2 billion in the state’s Revenue Shortfall Reserve and another $6.6 billion in unreserved, undesignated surplus.

With the 2023 legislative session set to convene in less than a month and the state’s fiscal year 2023 budget slated for fine-tuning, some say it’s a good time for the state to review how it sets its budget — and how it spends, or doesn’t spend, its money.

What’s Happening

While Georgia’s reveling in its stellar credit-rating and record $12 billion surplus, some state agencies have been operating in recent years with smaller budgets and fewer full-time staff. Education and health care, for instance, bore the brunt of budget cuts in fiscal year 2021 to the combined tune of nearly $1 billion.

“Undeniably, our current level of spending is much lower than what we're collecting, and what we're likely to continue to collect in tax revenue,” said Danny Kanso, director of legislative strategy and senior fiscal analyst at The Georgia Budget & Policy Institute.

Kanso, who wrote a report in August analyzing the state’s record surplus, said the state “has considerable room to adjust its revenue estimate upward,” to spend more.

But fiscal conservatives point to the money the state has spent: $1 billion for 10 months worth of gas tax holidays and another $2 billion in income tax rebates and cash assistance to low-income residents who receive Medicaid, PeachCare for Kids, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or the state’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

In addition, Kemp is promising another tax refund in 2023, pending legislative approval.

While the state is flush with cash that state officials insist is necessary to address unforeseen emergencies, Georgians are struggling with the fallout of inflation and are facing a possible recession next year.

The question for some, then, is: Why should I care?

The Frugal Uncle

Think of Georgia as a frugal uncle who’s lived below his means for years even when times didn’t call for it. He pays for that fishing trip or vacation with cash, not credit — much to the chagrin of his family who needle him about his frugalness.

When times get tough, this frugal Georgian keeps trips to the grocery store and utility usage to a minimum, and as such, his austerity has helped him build a healthy savings and a respectable investment portfolio while also socking away money for emergencies. In addition, his carefulness and frugality has enabled him to maintain an impeccable credit score that affords him the best interest rate on the family’s mortgage.

“The state does a good job of not biting off more than it can chew when it comes to spending,” said Kyle Wingfield, president and chief executive of the Atlanta-based conservative think tank Georgia Public Policy Foundation. “The bond rating agencies believe the state is well-managed. It also reflects that we have a very stable fiscal environment.”

State government bond ratings give banks and other lenders a sense of whether a state or municipality can pay its debts. The higher the rating — AAA is the highest — the less chance of default. Georgia has had a AAA bond from the three major rating agencies — Fitch Group, Moody’s Investor Services and Standard and Poor’s — for more than 25 years. In addition to bragging rights, Georgia’s stellar credit rating allows the state to get the best possible rates when it goes to market to sell state bonds.

Tony West, deputy state director for Americans for Prosperity Georgia, agrees. “It’s an enviable position to be in,” West said. “It shows most of the country that we carefully manage the people’s money.”

As Georgia’s fiscal economist, Jeff Dorfman is one of Kemp’s key advisors. The state’s cautious money management is sacrosanct, he says.

“One thing that's very important, and the governor insists on this, is it [spending the reserves] has to be a one-time thing,” Dorfman said. “We can't take these extra monies and spend them on an annual recurring thing because then when the money's gone, now you're burdening the taxpayers and you're gonna have to raise taxes to keep paying for that.”

Explains Dorfman, “That's why we're looking at water and sewer systems and rural broadband and a lot of things like that where we can pay upfront costs with the money we have now. If we can do infrastructure investments and lower our ongoing expense structure, this is our ultimate goal.”

Why It Matters

In August, the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI), a liberal Atlanta-based nonprofit that analyzes tax policies and proposed budgets, released a report on the state’s record surplus.

“The state has prioritized growing surplus accounts over funding for programs, services and workforce,” states the August 2 report, “With Record Surplus, Georgia Stands at a Crossroads Ahead of Pivotal Budget Session,” written by Kanso.

Even though Georgia is expected to see continued revenue growth, it continues to spend less per resident than it did before the Great Recession 14 years ago, Kanso wrote in the report. “Even after accounting for a potential economic recession and the effects of tapering federal spending, it appears that consecutive years of conservative revenue estimates have compounded such that Georgia could raise significantly more than it currently plans to spend in the upcoming year.”

According to the report, in fiscal year 2023, Georgia plans to spend about $1.3 billion less, or about $121 less per resident, than it did before the Great Recession, when Georgia’s budget was upended by spending cuts the state made in response to weakened revenue collections.

The report urged state leaders “to make long-deferred investments and make up ground lost to over a decade of austerity.

“This means that even if state revenue collections come in below the revenue estimate set by the governor, Georgia’s existing reserves are almost certain to be more than sufficient to cover the difference,” the report said.

When asked if Georgia is hoarding money, Kanso replied: “that remains to be seen in how we are going to adjust [the budget] in the upcoming legislative session.”

Former state lawmaker Eric Johnson sees it differently.

“You've got to be prepared to have some savings for your emergencies,” Johnson, former president pro tem of the state senate, told State Affairs. “The economy is booming now, but I've been through two downturns where we've had to cut and that's a painful process. Look how long it took to get the education funding back up.

“The state’s got the resources now but everybody’s anticipating a recession in the next year or so. You’ve got to be able to live through the downturns without the minimal amount of cuts to programs,” said Johnson.

While Georgia's large surplus is not usual, this year’s record surplus has emerged from other unexpected circumstances.

Georgia – like the rest of the country – saw unprecedented surpluses last year, thanks to a booming stock market that led to higher-than-expected tax revenues, especially in capital gains taxes, Dorfman said.

“The stock market did tremendously well in 2021. In April 2022 when everybody filed their 2021 taxes, we collected an extra $3 billion in capital gains taxes on stock market profits. And literally, I mean that came in like a week or so right around the filing deadline.

“It happened to every state and to the federal government,” he added. “Everybody got more taxes than they predicted because of the stock market profits.”

Billions in federal pandemic aid also helped grow reserves.

Of the $5.2 trillion the U.S. government committed in response to the pandemic since early 2020, about one-sixth went to state governments for the public health emergency and to boost their economic recovery, according to Pew Trust. The federal government gave more than $800 billion in grants to states through six pieces of COVID-19 legislation. Georgia received more than $17 billion in COVID-related relief.

States saw their collective rainy day funds grow by $37.7 billion, about 50 percent from the previous year, “driving the total held among all states to a record of $114.6 billion,” according to Pew.

What’s Next

While it’s tempting to take the $12 billion surplus and splurge, “We don’t just spend the money because we have the money,” Dorfman said, citing California as a cautionary tale.

Flush with a record $98 billion surplus last year, California now faces a $25 billion deficit next fiscal year. “They gave a ton of it away and they spent a lot of it, including some on continuing expenses, and as our [U.S.] economy slowed down, they got less revenue than they thought and now they’re short,” Dorfman said, adding, “We certainly don't need to have $12 billion to get the AAA bond rating because we had it when we had $2 billion but we're much better off with the larger reserves we have now.”

A AAA-rating is so sacred that some states refuse to spend their largesse for fear of losing their impeccable standing.

Research by Pew found that “even in states with the highest rating, policymakers often are unsure about how best to manage their rainy-day funds to earn or keep high credit ratings. As a result, some state officials are reluctant to tap reserves even during recessions for fear of a ratings downgrade.”

Former Baltimore state Sen. Barbara Hoffman said in Pew’s 2017 report, “Rainy Day Funds and State Credit Ratings”: “We never use ours, and that’s one of the reasons we have a triple-A rating in good economic times and bad.”

Maryland is one of the 14 states with a AAA rating. In addition to Georgia and Maryland, the other states are Indiana, Delaware, Iowa, Florida, Tennessee, South Dakota, Virginia, North Carolina, Utah, Texas, Virginia and Missouri.

William Ratchford, former director of the Maryland General Assembly’s fiscal services department, noted in the report that to most legislators, the purpose of the rainy-day fund is to maintain the AAA rating. “If we have future needs, we’ll deal with that. But it’s never been, ‘Well we can always use the rainy day fund.’ It just isn’t how they approach it,” he said.

But Georgia’s not going to keep its $12 billion reserves forever, Dorfman said. “We’ll take our time and spend it wisely and make sure we are very clear-eyed and realistic in our revenue forecasts.”

In Case You Missed It

TEACHERS, BRIDGES, TAX REFUNDS: WHAT GEORGIA’S $5 BILLION SURPLUS CAN BUY

GEORGIA’S RECORD $5B BUDGET SURPLUS SETS UP HIGH STAKES LEGISLATIVE SESSION

Have questions or comments about the state’s AAA bond rating? Contact Tammy Joyner on Twitter @LVJOYNER.

And Subscribe to State Affairs today!

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

Spotted sea trout surged, shorebirds struggled, and the water’s safe for swimming

The Gist

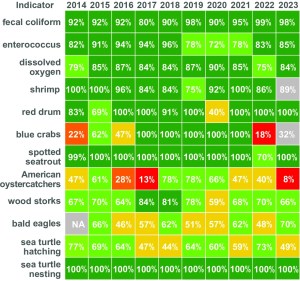

Spotted sea trout flourished, sea turtles and shorebirds struggled, and blue crabs crawled their way out of trouble in ever-warming coastal waters last year. Those are a few of the findings in the Coastal Resources Division’s annual Coastal Georgia Ecosystem Report Card, released today.

What’s Happening

Every year since 2014, the Department of Natural Resources collects data on 12 indicators of coastal ecosystem health that impact humans, fisheries and wildlife and issues a report card.

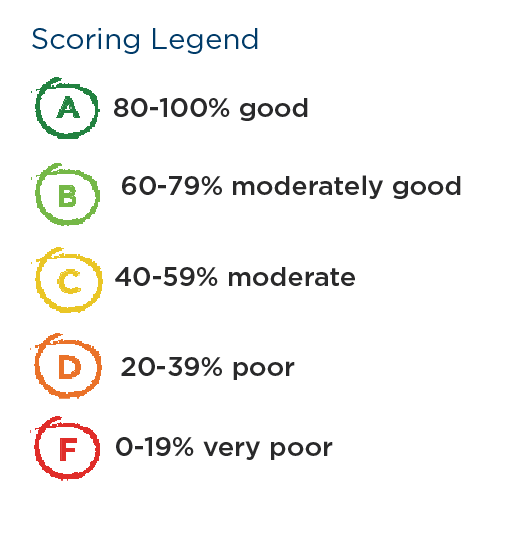

Based on data collected in 2023, Georgia’s coastal ecosystem this year earned a B, which equates to a “moderately good health score” of 78%, up from last year’s score of 74%.

Click here to see the full 2023 Coastal Ecosystem Report Card.

The ecosystem indicators and scoring methods for the report card were developed with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, which has helped to create other ecosystem health assessments around the country.

This year, red drum remained plentiful and spotted sea trout numbers improved, as the sea trout count in the Wassaw and Ossabaw sound systems rebounded. The report said a 2016 regulation that increased the minimum catch size limit for sea trout is helping.

Shrimp numbers improved a bit, too, just in time for their recognition as the state’s official crustacean by the Georgia Legislature this year.

According to the Department of Natural Resources, the dockside amount of wild-caught “food shrimp” brought in by commercial fisheries increased to 2.6 million pounds from 2.1 million pounds in 2023 (though the overall dockside value of Georgia shrimp decreased to $9.4 million from $11.3 million, largely due to competition from foreign suppliers of lower-priced, imported frozen shrimp).

Blue crabs got a D in the report but improved from a score of 18% last year to 32%. Warm coastal waters and increased salinity in the water could explain why crab numbers were low in the survey, but the report also noted its sample size of crab was skewed because its trawling vessel was out of commission for part of 2023. The amount of blue crab caught by commercial fisheries increased to 3.4 million pounds in 2023 from 3.1 million pounds in 2022, with a dockside value of $7 million.

Overall, the dockside value of all commercial fisheries tracked by Natural Resources in Georgia in 2023 was $19.7 million, about $2 million less than in 2022.

The lowest scorers

As was the case last year, shorebirds in general and American oystercatchers in particular were the animals that scored the lowest. Wildlife biologist Tim Keyes said big storms that hit the coast washed out and degraded the beaches and marsh islands where oystercatchers nest. Shorebirds, including wood storks, were also preyed on by raccoons, opossum, coyotes and hogs that live in remote coastal areas.

Keyes said the Coastal Resources Division is working with the Army Corps of Engineers to build new 10-foot-high sand islands and sandbars using dredged-up sediment near Cumberland Island and along the Intracoastal Waterway to give the birds a boost and a better place to roost.

Loggerhead sea turtles, a threatened species, dropped to a C grade from a B, primarily due to increased predation. Sea turtle nesting sites were plentiful once again, with 3,431 loggerhead nests located, and a 52% emergence rate for hatchlings. But many of the eggs and baby turtles were gobbled by wild hogs, raccoons, coyotes before they could make their journey to the sea, according to the Wildlife Resources Division report.

The good news

The report contains good news for humans who like to cavort in coastal waters, as the water quality index received an A, at 89%. Overall indicators show the water is generally safe to swim in and to eat local shellfish, that oxygen levels support fish and other species, and bacteria is at acceptably low levels.

Read this related story:

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

Democratic incumbents vie for redrawn House district seat

ATLANTA — Democratic incumbents running in south DeKalb County’s newly drawn District 90 are in a political predicament: Longtime comrades, they now find themselves pitted against each other.

Reps. Saira Draper and Becky Evans met Wednesday on the debate stage at St. John’s Lutheran Church to make the case for why voters should choose them for the newly drawn district in the upcoming May primary.

Mike St. Louis, chair of the Druid Hills Civic Association and moderator of the hourlong debate, lamented the“gratuitous” pairing of two Democratic incumbents in the same district drawn by Republicans who controlled the special legislative session on redistricting last year. The process was an effort to comply with a judge’s order to add more majority-Black districts.

House District 90, which Draper represents, will still include the part of Atlanta that is in DeKalb County, as well as six new precincts in southwest DeKalb that were in District 89, where Evans serves. Each was elected in districts that were and remain majority-Black, solid-blue districts.

No Republican or independent candidates qualified for the 2024 election for the new District 90.

Draper and Evans began and ended Wednesday’s debate acknowledging their respect for each other, and their chagrin over their political predicament, while trying to draw distinctions on their legislative records and strengths.

“This was not something that either of us asked for. It’s not something that either of us wanted,” Draper said. “And to me, it really underscores the fact that we have to get the majority in Georgia.”

Draper, a civil rights attorney serving in the House since 2023, said what makes her “the best person for the job … really boils down to democracy and diversity.” She described herself as an elections and voting rights expert who helped to “flip Georgia blue for the first time in 30 years” during the 2020 presidential election and the 2022 midterms, when she said she “led the voting rights efforts” in Georgia for President Joe Biden and U.S. Sens. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, for whom she oversaw campaign staff and thousands of volunteers.

Draper said she’s now fighting to bring Democratic majorities back to the state House and Senate, which she estimated will likely take four to six years.

In the meantime, she said she has worked to push through what legislation she can in the Republican-controlled House and cited as a small victory House Bill 1207, a bill she crafted that requires advanced proofing of ballots by candidates and election supervisors. Draper sought out five Republicans as co-signers to gain majority support for the bill, which passed in both chambers and awaits Gov. Brian Kemp’s signature.

Noting that “diversity is a central tenet to the Democratic Party,” Draper said, “as a woman of color and as an immigrant, I bring perspectives to the table that are underrepresented at the Capitol.”

Draper immigrated to the U.S. when she was 6 years old from England, where her Spanish mother and Pakistani father met. “That makes me Spakistani,” she said, eliciting laughter from the audience. “But it also makes me the only member of the Georgia General Assembly who is a member of the Hispanic caucus and the Asian American Pacific [Islander] caucus.”

Evans, a community organizer and political operative who has served in the House since 2019, emphasized her six years of experience building relationships with fellow legislators and delivering on measures to support education, the environment, gun safety and housing.

“And I’m 100% pro-choice, 100% pro-LGBTQ and 100% pro-health care expansion,” Evans said, adding she is proud of her work developing legislation to promote literacy among school children over the past two years, including writing a bill last year to create the Georgia Council on Literacy and another bill to ensure that children are screened for dyslexia and other reading challenges and that teachers are trained in evidence-based reading and writing instruction.

When her bills didn’t pass from the House to the Senate by the Crossover Day deadline in 2023, Evans said she persuaded Republican lawmakers in the Senate to adopt her legislation, which then passed. She now serves on the 30-member literacy council, which she said is working “to make sure that all of our children will have the broadest possible futures and that they can all learn how to read.”

Evans also said she was “proud to deliver this session $7.4 million in [federal] gun violence prevention awareness funds that will go out to community groups” and to support the passage of a bipartisan Senate bill that will give “[sales] tax breaks [on gun safety devices] where people are using their guns responsibly.” She said she also advocated for adding new funding for school security grants to the education budget, which was approved.

The candidates took similar positions on many issues, both decrying the private school voucher bill they said would drain funds from public schools, and the need for the state to better fund impoverished school districts. They described their individual efforts to curtail gun violence and promote voting rights, as well as detailed their years of experience in ground-level get-out-the-vote efforts in DeKalb County and metro Atlanta. Draper and Evans also expressed measured support of the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, which they said is needed to train police and first responders.

Among the 40 or so people in the audience, Lora Wuennenberg, 68, a Kirkwood resident and program manager at the humanitarian nonprofit CARE, said she emerged from the debate torn between the two candidates. Noting they have similar positions on the major issues she cares about, including public education, she said Draper, her current representative, impressed her as an “an activist who can mobilize people and is willing to stand up and stand out on some of the issues that may not be getting enough attention.”

“Becky seemed more of a practical, behind-the-scenes organizer, someone who understands the bureaucracy of government and has a lot of established contacts,” Wuennenberg said, noting Evans has worked across the aisle and “found entry points” to get legislation passed. “In the Republican-controlled House, maybe she can be more effective than Saira.”

Wuennenberg said over the next few weeks she’ll follow the candidates and look to see “how Saira thinks she can mobilize support for the bread-and-butter issues that have an impact on people’s lives” in the next legislative session.

Arica Schuett, 36, a Ph.D. candidate in political science at Emory who lives in Druid Hills, said she also needs to spend more time studying the candidates.

She said Draper’s focus “on mobilizing voters and removing barriers to election participation resonated” with her, while Evans’ “experience and her ability to to work with constituencies that include Republicans is important. So getting a better understanding of how each candidate would manage their position in a really Republican Legislature is what’s important to me.”

Schuett said she plans to dive deeper into their proposed legislation and voting records. “I kind of want to look a little bit more at what they’ve done, right?”

The primary election will take place May 21.

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

Barbershop talks and hip-hop summits: Georgia Black legislators’ group has big plans to build coalitions, boost voter rolls

The nation’s largest gathering of Black lawmakers is slated to meet in Atlanta this summer to discuss ways to boost voter participation nationwide ahead of the upcoming fall elections.

The Aug. 2-4 conference theme is “Testing 1, 2, 3.” The meeting will be the precursor to a series of events the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus plans to hold heading into the November presidential election.

“Because we’re the largest Black caucus in the nation, we’re reaching out to all of the caucuses from across the nation,” Rep. Carl Gilliard, D-Savannah, chairman of the 74-member Georgia caucus, told State Affairs. “This is the first time that I think we’re doing a total reach-out to all of the Black caucuses. We share a lot of similarities. Whether it’s voter suppression in Georgia, the same laws are going to be tried in Tennessee and the same laws are going to be tried in Florida. We share a lot of commonalities.”

Next week, for instance, the Georgia caucus is scheduled to issue a statement supporting efforts to pass a hate crimes bill in South Carolina. The bill passed in the House but stalled in the Senate, Gilliard noted.

Over 700 Black legislators represent about 60 million Americans, according to the National Black Caucus of State Legislators. In addition to the Georgia caucus, Black caucuses exist in nearly three dozen states.

Shortly after the August convention, the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus will embark on a 14-city tour throughout Georgia to focus on “getting out the vote.”

“We’re not going to tell them who to vote for,” Gilliard said of voters. “But what is happening right now is no one is talking to the people. And if the election were held today, we all would be in trouble because no one is talking or meeting the people where they’re at.”

The tour is a continuation of various actions the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus has taken this year to align with other organizations of people of color on common causes.

In March, the caucus joined forces with the Asian American Pacific Islander and Hispanic caucuses for a tri-caucus town hall. It was the first time the three groups have aligned. The Black caucus also has “reached out to partner with the Hindus of North America population and the diaspora,” Gilliard said.

“What we’re trying to do is form a coalition to get to as many diverse groups of people as we can,” he said.

Gilliard said the lack of individual and collective involvement in communities he’s seeing concerns him. It’s a far cry from four years ago.

In 2020, the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, an unarmed Black man murdered while jogging in Glynn County, and Breonna Taylor, a Black woman killed by Louisville, Kentucky police serving a no-knock warrant for drug suspicion, led to more than 450 protests nationwide and on three continents.

That same year, former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams led an effort to increase the voter rolls for the 2020 presidential election. Fair Fight and the New Georgia Projects, two groups Abrams founded, registered more than 800,000 new voters.

That level of community and political engagement has since subsided, Gilliard said.

“People don’t know what’s going on,” Gilliard said. “No one is really talking to the people. You’ve got a presidential election. I’m talking about on both [political] sides. There are rallies and different events being held, but nobody has gone to the barbershop. No one has gone to the community centers or the neighborhoods. We’re going to be empowering those communities by going and taking those townhall meetings right where they’re at, not in a big municipality but in community centers and neighborhoods.”

The caucus also plans to hold a hip-hop summit to reach young people, many of whom are skeptical of both political parties.

“They’re forming their own opinions,” Gilliard said. “They’re saying, ‘Forget about Trump. We need to hear something different.’ That’s just their perception. That’s why I’m really quietly championing the young candidates behind the scenes who are running right now because we need young leaders.

“We have to get as many people together, but we also have to get them ready to work.”

Have questions, comments or tips? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss any news you need to know.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram@StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

Special prosecutor to decide if Lt. Gov. Jones should face criminal charges in 2020 election-meddling case

Lt. Gov. Burt Jones will face scrutiny over whether he should be criminally charged for alleged meddling in the 2020 presidential election in Georgia.

The Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia said Thursday it has assigned Executive Director Pete Skandalakis as the special prosecutor to handle the case because Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis is barred from investigating Jones. The council is a nonpartisan state advocacy agency for district attorneys.

In July 2022, Superior Court Judge Robert McBurney blocked Willis from investigating Jones because her actions were an “actual and untenable” conflict of interest. At the time, Willis had hosted a campaign fundraiser for Jones’ Democratic rival, Charlie Bailey, and donated to his campaign when both men were running for lieutenant governor. Willis is currently involved in an election interference case she brought against former President Donald Trump and 18 others.

McBurney’s ruling left it up to the council to decide whether Jones should be criminally charged.

“I’m happy to see this process move forward and look forward to the opportunity to get this charade behind me,” Jones said in a statement issued Thursday. “Fani Willis has made a mockery of this legal process, as she tends to do. I look forward to a quick resolution and moving forward with the business of the state of Georgia.”

The council cited state bar rules in its news release and said there would be no further comments.

Skandalakis’ appointment marks another step in the ongoing political odyssey for Jones and other lawmakers over charges that they served as “false” electors to help Trump overturn the 2020 presidential election in Georgia.

Jones is one of 16 alleged “false” electors in Georgia who gathered at the state capitol on Dec. 14, 2020, to cast ballots for Trump and then sent their false certification of his victory to the National Archives and the governor’s office.

Jones has denied any wrongdoing, saying he and other electors were acting on the advice of lawyers to preserve Trump’s chances in Georgia in case the former president won a court challenge that was pending at the time. Jones was a state senator during the 2020 election.

Trump’s campaign enlisted an alternate slate of electors in 2020 in a number of swing states where Trump was defeated, as part of an effort to circumvent the outcome of the voting, The New York Times reported Thursday.

Have questions? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss any news you need to know.

X @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs