Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoWhy Democrats are finding more success in the Indiana Statehouse this year

House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, and House Minority Leader Phil GiaQuinta, D-Fort Wayne, talk during an event on March 7, 2023. (Credit: Kaitlin Lange)

- As superminorities in the Indiana House and Senate, Democrats can move bills only if Republicans allow them.

- The last two years have been particularly challenging for Democratic lawmakers.

- Democrats are finding more success this year, but everyone has different theories on why.

South Bend Fire Chief Carl Buchanon is all but certain it’s too late for him.

Over his 37 years in the department, he’s been exposed to cancer-causing chemicals found in firefighting foam and gear known as PFAS. Multiple former South Bend firefighters have died of cancer, and firefighters are 14% more likely to die of cancer than the general public.

What Buchanon doesn’t know is how many of the chemicals are flowing through his veins. A bill under consideration by Indiana lawmakers would direct the state to begin testing firefighters.

“Maybe it’ll help me,” Buchanan said during committee testimony on the bill, “but I’m more concerned with it helping those that are after me.”

House Bill 1219 also amounts to a legislative victory for Democrats, who haven’t been able to say that too often in recent years.

The Indiana General Assembly is overwhelmingly controlled by Republicans. Not only do they hold the votes, they also decide whether a Democratic bill can even be heard by lawmakers in the first place. And, historically, Indiana supermajorities of both political stripes have tended to exercise that discretion more often than not.

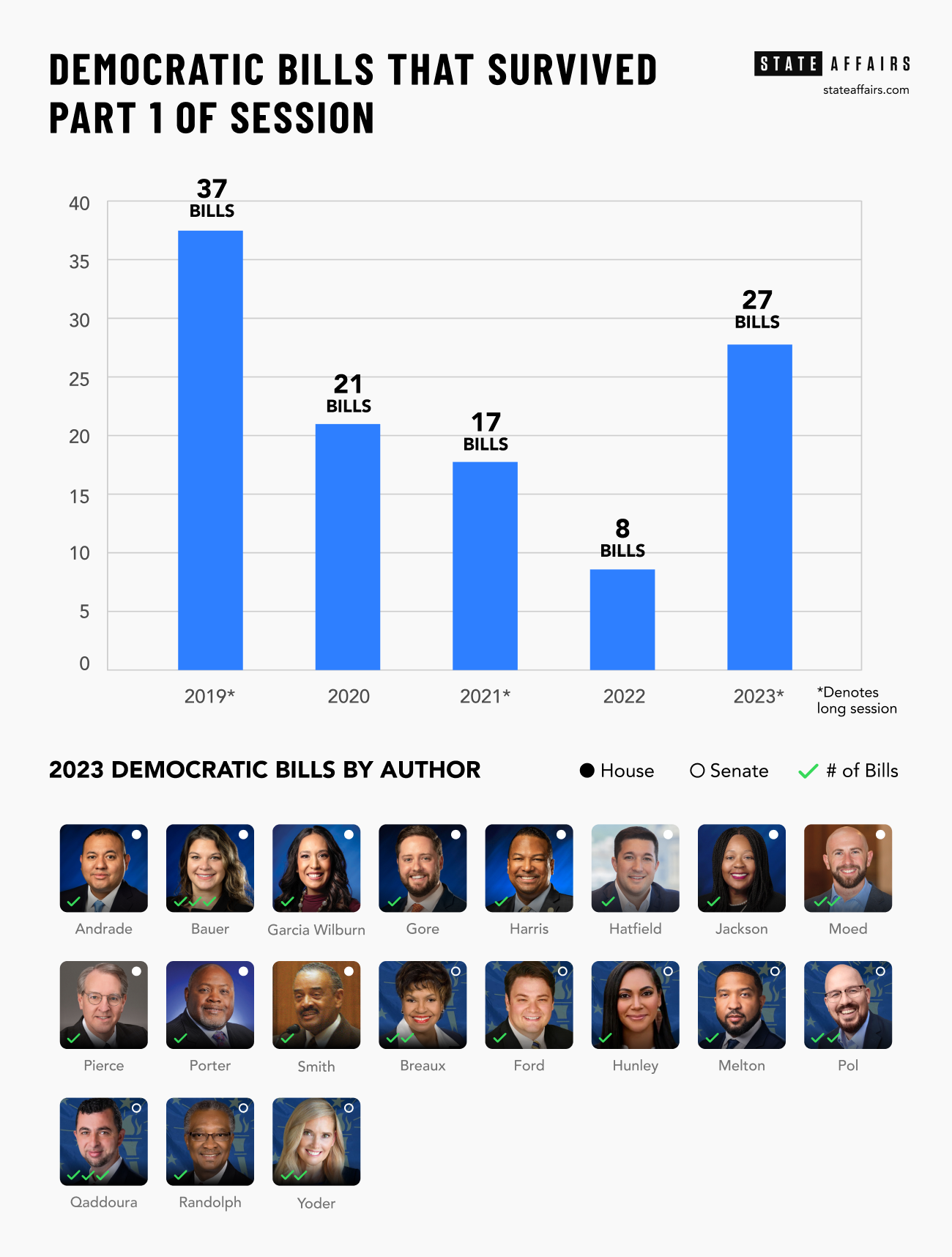

This year, though, Democrats moved 27 bills in the first half of session.

That’s more than the last two years — combined.

Rep. Maureen Bauer, D-South Bend, filed legislation to address PFAS last year and the year before, but neither of those bills moved. This year’s House Bill 1219 — which moved through the House and has picked up powerful Republican co-sponsors in the Senate— was her first success.

“With one party rule in the House, the Senate and the governor, I think it can be easy to only hear one party’s policies or ideas,” said Bauer, who also moved two other bills this year. “But when we come down here I represent Democrats and Republicans alike. I’m reminded of that often.”

To be clear, it’s not that Democrats are passing an outsized number of bills. The Democratic-led bills still in play make up less than 8% of the bills that advanced in either chamber during the first leg of session, despite Democrats holding a quarter of all legislative seats. That doesn’t include bills in which Democrats are a secondary author.

Nor is partisanship dead. Democrats have pushed back against a flood of bills they say would hurt transgender Hoosiers, and no Democrat voted for the House budget which aims to expand school choice vouchers.

The ideological divide on social issues has arguably never been greater in the halls of the Statehouse.

So, why are Republicans allowing Democrats to move more bills this year?

Everyone has their own theory. Maybe Democrats are simply introducing bills with bipartisan interest. Or maybe it’s a concerted effort to stave off the bitterness now common in Congress and other statehouses. Or maybe House Speaker Todd Huston and President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray have grown comfortable as they’ve collected more years of power.

Or there’s Huston’s explanation: The state has moved on from the pandemic when how people governed and communicated was different.

A return to normalcy

Huston, R-Fishers, was not surprised to learn that Democrats moved more bills this year. He characterized the increase as a return to “normal” times following disruptions driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, House lawmakers gathered in a larger, makeshift space in the Indiana Government Center South building to enable social distancing. They only met once per week at the beginning to reduce contact. The Senate, too, spread out over the two floors of the Senate chamber.

And just like others around the world, lawmakers weren’t fraternizing as much as they typically would. Taken together, that meant less communication and relationship-building between the caucuses.

Only 17 Democratic bills made it past a floor vote that year, compared to 27 this year, despite both sessions being longer budget years.

Perhaps nothing illustrated the tension back in 2021 more than when a verbal fight broke out in the House’s temporary chamber after Republican lawmakers booed Black Democratic lawmakers who called a bill discriminatory during floor debate.

At one point, two lawmakers had to be physically separated just outside of the chamber. All 14 Black lawmakers in the Statehouse were Democrats.

By 2022, lawmakers had stopped sitting six feet apart, but Huston said the relationships between lawmakers hadn’t returned to normal yet. There was an ideological divide on how to handle yet another COVID-19 surge, as some lawmakers wore masks and others declined to get vaccinated. That year, only eight Democrat-led bills survived the first half of session in either chamber.

“I’ve heard overwhelmingly how much better communication has been on both sides of the aisle, within committees,” Huston said. “This year we’re back to having the normal types of relationships we can have where people can spend time outside the chamber talking to each other in their offices and around the Statehouse.”

The numbers bear out Huston’s theory. The number of Democratic bills advancing so far this session mostly match those in pre-COVID times. In 2019, 37 bills moved during the first half of the session.

Other theories

Of course, there are other theories.

Yes, 2021 was impacted by COVID-19, but it also was Huston’s first session as speaker. In the Senate, Bray was in just his third session as the leader.

Mike Murphy, a former Republican lawmaker who spent most of his tenure as part of the minority party, emphasized that how many minority party bills get passed depends on the attitudes of leadership.

“Speaker Huston and President Pro Tem Bray have got their sea legs, so to speak, and got more comfortable as leaders of these two supermajorities,” Murphy said. “Their caucus members have tremendous confidence in them, which gives them the ability to be a little more magnanimous when dealing with the minority party’s ideas.”

(Credit: Ronni Moore)

To Murphy’s point: Huston and Bray both said they tell committee chairs to take testimony on the best bills, regardless of who wrote them.

Multiple people interviewed by State Affairs agreed that Indiana legislative leaders do not want to see their chambers devolve into the bitterness gripping Congress and other statehouses. And a majority of Americans want government officials to work with those across the aisle, multiple polls have shown, even if that’s not necessarily how people vote.

“I take some pride in the fact that while we’re a supermajority, we still want the other side of the party at the table,” Bray told State Affairs, “and candidly they intend to be there and add value.”

Bipartisan bills

Andy Downs, emeritus associate professor of political science at Purdue University Fort Wayne, has a more simple suggestion: Democrats are carrying bills that have bipartisan interest this year.

“Democrats have managed to identify issues that cut across normal partisan divides,” Downs said, “and in doing so have managed to find less resistance.”

Some could be lifesaving. Aside from the PFAS legislation, Democrats championed a bill focused on decreasing fatal car crashes.

Another bill Bauer authored seeks to close loopholes in Indiana’s child seduction law so the criminal charge applies to youth sports coaches who are not employed by schools. It passed the House and already received a hearing and committee vote on the Senate side, too.

“I think it’s hard to ignore something like that as a chair,” Bauer said. “At a time when it might seem like we don’t have common ground, we can see an area where we can come together and pass bills out unanimously.”

Ironically, having a supermajority actually better enables Republican leaders to support Democratic bills, according to insiders and experts. If the margins were closer, Republicans wouldn’t be motivated to help any Democrats, particularly if it could help a Democrat hang on to a seat.

This year, even Democrats from some of the state’s most competitive districts, such as Rep. Victoria Garcia Wilburn, moved legislation.

Garcia Wilburn, a freshman who won a competitive Hamilton County district by just 1 percentage point in 2022, pushed a bill through the House that seeks to improve police officers’ mental health and prevent suicide.

Likewise, Rep. Mitch Gore, a Democrat from the southeast side of Indianapolis, was able to advance a gun bill, a surprising feat for any Democrat, let alone one in a more competitive district.

“There’s no how-to book to get a bill passed out there,” House Minority Leader Phil GiaQuinta said. “We try to be pragmatic problem solvers, and on top of that, I think our members do a really good job of forming relationships with chairs.”

Holcomb and Democrats are on the same page

The other strange phenomenon that could be helping Democrats is that Gov. Eric Holcomb included items in his 2023 legislative agenda that were historically championed by Democrats. One example: Holcomb wants to do away with textbook fees for families of K-12 students.

He also wants to expand the 21st Century Scholars program by automatically enrolling eligible students, an idea Democrats have endorsed for years. The program covers the cost of tuition for students from low-income families at many Indiana colleges and universities.

When some parents begin wondering how their high school students will afford college, it’s already too late because the program requires families to apply while the kids are in eighth grade.

State Rep. Earl Harris, Jr., D-East Chicago, has been pursuing a legislative fix for at least a couple years. In his pitches to other lawmakers, Harris has talked about how the bill would enable families to overcome a costly barrier to send their children to college.

But, he notes, the state of Indiana also would benefit from a workforce that is increasingly educated. The latter point is of particular interest to a Republican supermajority seeking to address a workforce shortage across several industries in Indiana.

"You mention workforce," Harris told State Affairs, "and pretty much everyone's ears are going to perk up."

This year his bill is finding important allies, including the Republican chairs of the House and Senate education committees.

It is also fortunate, he said, that Holcomb’s legislative agenda sought to expand automatic enrollment in the program. The two discussed his bill when the Indiana Black Legislative Caucus met with the governor on Feb. 14.

Typically lawmakers from the same party as the governor carry his priority bills. But no Republican filed legislation related to automatic enrollment this year, so if Republican chairs wanted to advance that part of Holcomb’s agenda, they needed to turn to a Democrat.

“Sometimes,” Harris said, “it’s just great timing.”

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, and House Minority Leader Phil GiaQuinta, D-Fort Wayne, talk during an event on March 7, 2023. (Credit: Kaitlin Lange)

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

Who is Jamie Reitenour? Indianapolis mom mobilized volunteers to make governor’s ballot

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is one in a series of profiles of the candidates running for Indiana governor.

ZIONSVILLE, Ind. — It wasn’t the largest campaign event the 2024 election cycle is likely to see.

About 15 people, some of them children, gathered on a rainy April night at Our Place Coffee, nestled just feet from the watchful eye of Zionsville’s Abraham Lincoln mural. But Republican gubernatorial candidate Jamie Reitenour, an Indianapolis mom with no previous political experience, spoke with every single one of them.

It was one part coffee-and-issues politicking and one part informal Bible study, complete with scripture quiz questions for the kids in attendance.

Reitenour, well-worn Bible in hand, shared her oft-repeated story of being called by God to run for governor about six years ago — a destiny confirmed by friends and strangers alike along the way, she said. This charge, she told the group, would allow her to rise above traditional campaign currency, such as fundraising dollars and polling numbers.

Suzanne and Shon Hough sponsored the event after meeting Reitenour at their shared church, Horizon Christian Fellowship in Lawrence.

“As soon as we met her, we knew this is someone to support,” Suzanne Hough said. “We knew she wasn’t a politician. She was called. She has a love and compassion for people.”

That is how Reitenour has made it this far — how she gathered the 4,500 state-mandated signatures to qualify for the May 7 primary ballot, how she’s made it onto a stage filled with more experienced and wealthier opponents. For more than a year, she’s hosted several small events per week throughout the state, traveling some 35,000 miles, by her count.

The dozen or so latte-sipping supporters had a part to play, the candidate said.

“Go to your contact lists and tell them about our Facebook,” Reitenour said. “We could reach 144 people today if we all did that.”

The call

Reitenour’s purpose changed in 2017 while walking through downtown Indianapolis with her husband, Nathan.

“I just heard a whisper: You’re going to be the governor of Indiana,” Reitenour told State Affairs.

The couple wandered over to the governor’s mansion.

“We looked at it and thought, ‘That does not look like our family,’” she recalled. “So I just put the calling on the shelf.”

Indiana requires gubernatorial candidates to have lived in the state for at least five years. She had only just moved from Michigan.

Reitenour believed the country was in a good spot under then-President Donald Trump. Why would she need to run?

“I just thought about it,” Reitenour said. “Why would the Lord call an ordinary person to something like that when the nation was doing so well? But the reality of scripture is that you see these times where people are called, and you can see the reasons for the calling around them.”

Her regular Bible contemplation soon took her to the Book of Nehemiah, who was a governor. Another sign, she said.

The state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic set off alarm bells for Reitenour, who considered steps like mask requirements an affront to personal liberty. She brings up the subject often, and it made it into her coffeehouse remarks.

“How am I in a conservative state, but I don’t feel free?” she told the crowd.

After COVID-19 and the election of President Joe Biden, Reitenour began to think more seriously about running for governor.

Her mission was affirmed first by a close friend, whom Reitenour said received a similar calling from God to help her candidacy, and then by strangers, whom she said confirmed her destiny during separate chance meetings at a Panera Bread location.

She began to meet with church groups and advocacy organizations that align with her views, including Moms for Liberty and Indiana Right to Life. Despite being referred to as an activist on the campaign trail, Reitenour said she is not part of any activism group.

Getting on the ballot

This network of like-minded supporters would soon serve as the volunteer arm of Reitenour’s campaign.

Indiana requires candidates for governor to collect at least 4,500 signatures from voters, including at least 500 from each of the state’s nine congressional districts. It’s a tall order even for seasoned politicians, who often hire specialized operatives for the task.

“The mystery of how we did that will also be the mystery of how we win,” Reitenour said.

She focused on growing supporters and gathering signatures at each small event she hosted, then mobilizing those attendees to gather still more for her.

“I had a formula in my heart for this that the Lord gave me at 4 a.m. one morning,” she said.

The campaign

Reitenour made the ballot, but she is the least-known candidate in a field that includes Sen. Mike Braun, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, former state Attorney General Curtis Hill, former state Secretary of Commerce Brad Chambers and Eric Doden, a Fort Wayne businessman and previous president of the Indiana Economic Development Corp.

She has no previous political experience. She is a stay-at-home mom who also homeschools her five children and volunteers through ministry. Her previous work experience includes compliance management at a mortgage company, secretarial work and even a stint as an assistant coach in women’s field hockey.

Reitenour was selected in the governor’s race by just 2% of respondents in a recent State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana poll, tying her with Hill for last place behind front-runner Braun (44%). She has consistently polled in the low single digits.

While other gubernatorial candidates can draw from years of campaign fundraising experience or millions in personal finances, Reitenour had raised just a little more than $54,000 as of March 31.

She has thus found herself paddling in a proverbial ocean of campaign spending.

The four top-polling candidates — Braun, Chambers, Doden and Crouch — have spent a combined $20 million.

After participating in the first gubernatorial debate on March 11, Reitenour did not qualify for a March 27 debate hosted by WISH-TV due to her fundraising numbers, as the television station required candidates to have raised $300,000 by December.

She was also excluded from a March 26 Fox59/CBS4 debate for not reaching a 5% polling threshold. She will be included in the final April 23 debate, hosted by the Indiana Debate Commission.

Reitenour has campaigned using a constantly shuffling group of volunteers. She has only one full-time employee: campaign assistant Casey Pierce, who met Reitenour through his mother’s church.

“It just felt like the right thing to do,” Pierce said of joining the campaign. He has never worked in politics before.

Pierce called his initial meeting with Reitenour “a Holy Spirit encounter.”

Reitenour’s platform

Reitenour described education as the state’s “greatest vulnerability,” and thus her primary platform.

“The next generation is not being educated well, and this has been a long time coming,” Reitenour said.

She has received guidance from the Hamilton County chapter of Moms for Liberty, which made national headlines in 2023 after using a quote attributed to Adolf Hitler in its first newsletter. The nonprofit, which pushes against socially minded education reforms like critical race theory, subsequently apologized.

Reitenour likewise opposes ideas like social-emotional learning in classrooms. Her plan also proposes removing technology from grades K-5, calling for private businesses to sponsor classrooms and requiring all students to pursue an apprenticeship before high school graduation.

She also favors an audit of the Indiana Economic Development Corp., tax cuts, a focus on investing in small towns and generally “pointing Indiana in the direction of family.”

The future

At her coffee shop appearance, Reitenour shied away from admitting her long odds in the race.

“The political system is meant to squeeze people out, but I am working against it,” she said.

She pledged to continue organizing no matter the primary election results.

About Reitenour

- Age: 44

- Hometown: Indianapolis

- Education: Psychology degree from Missouri State University

- Family: Married to Nathan Reitenour, with five children, ages 13, 11, 10, 9 and 4

- Job: Stay-at-home mom, homeschool teacher

- Work history: Former compliance manager at Windsor Capital Mortgage, former athletic director at Calvary Christian School (at Calvary Chapel Vista church in California)

Read these related stories

- Eric Doden is running from behind but hopes his ‘bold vision’ will propel him forward

- Suzanne Crouch positions herself as a ‘different’ candidate for the voiceless

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Child care: Where Republican candidates for governor stand

Six candidates are seeking the Republican nomination for Indiana governor in the May 7 primary. State Affairs is providing looks at their stances on several issues. Jennifer McCormick is unopposed for the Democratic nomination.

Indiana’s high cost of child care ranks as a primary concern for many of the state’s families.

According to Child Care Aware of America, a nonprofit organization that studies child care costs, Indiana ranks as the eighth most expensive state for infant and toddler care. The cost for caring for a baby averages 14.5% of a family’s median income, while toddler care is 12.9%.

Only 5% of Indiana families can afford infant care, the Economic Policy Institute found.

State Affairs asked each of the six Republicans vying for Indiana governor — U.S. Sen. Mike Braun, former state Secretary of Commerce Brad Chambers, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, Fort Wayne businessman Eric Doden, former state Attorney General Curtis Hill and Indianapolis mother Jamie Reitenour — how they would lower Indiana families’ child care costs if elected.

Here are their responses.

Mike Braun

“The high cost of child care burdens Hoosier families and businesses, who are trying to recruit and retain the best workers. As governor, I am open to and will work on solutions that will reduce the cost of child care, which is a win for our economy and families.”

Brad Chambers

“As governor, I’ll explore strategic expansions of all-day pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds, including potentially increasing the income eligibility level for state-funded pre-K programs. I’ll create a state-level child care tax credit that requires recipients to work to be eligible to receive it.”

Chambers said he would also explore incentives for employer-sponsored child care.

Suzanne Crouch

“First, I would lead the effort to eliminate the state’s individual income tax, which will mean more money in families’ pockets and help reduce the financial strain of child care expenses … As governor, I would propose that the General Assembly put a priority on early childhood education throughout Indiana.”

Crouch would also support the expansion of at-home and religious-based child care, she said, noting Indiana has “some of the highest relative child care costs in the country.”

Eric Doden

“I’ve offered a bold plan to expand pre-K access to every community in the state. By partnering with communities, nonprofits and education partners, we will begin addressing this important need. … We need a state with thriving communities and access to opportunity. Cost of child care concerns are downstream of family formation rates, good-paying jobs, home ownership and a host of other economic and community issues.”

Curtis Hill

“The government is not responsible for providing child care for private sector employees. Its responsibility is to dismantle the licensing and regulatory burden that prohibits new child care providers from entering the market. If we want to lower the cost of child care, we must cut the government regulations forcing child care facilities to either close or raise prices to meet unnecessary government requirements.”

Jamie Reitenour

“We cannot bear down on taxpayers for everything. We just cannot do it. But we can talk to the private sector and reason together. Can we have in-house day cares at offices? Yes. Can we have employers operate growth centers for employees’ kids? Yes. Taxpayers are not the answer; the private sector is. With competition for qualified workers, larger businesses already employ creative benefits, including child care assistance, to attract talent.”

Read these related stories:

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Poll finds Holcomb popular among Republicans even as potential successors keep distance

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb remains popular among Republicans, according to a State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana poll, even as the GOP candidates to take his place have kept their political distance from him. The polling results released Thursday show Holcomb with an overall positive job-approval rating of 69% among self-identified Republicans and Republican-leaning independents. The results …

‘It’s sort of a blowout’: Braun holds commanding lead in ‘State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana’ poll

U.S. Sen. Mike Braun holds a commanding lead in a new State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana poll of likely Hoosier Republican voters in the May 7 gubernatorial primary. Asked who they would vote for if the primary were held today, 44% of respondents picked Braun. Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch trailed with 10% of the vote, and …