Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoChief Justice Loretta Rush on mental health, bail and diversionary courts

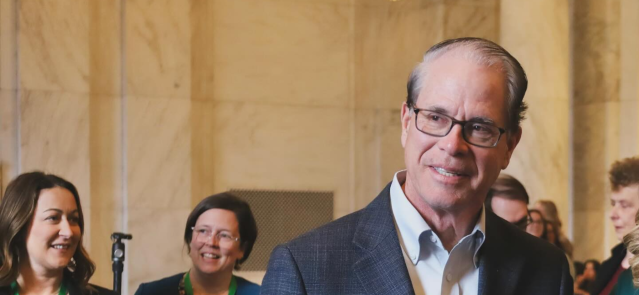

Indiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Loretta Rush chats with President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, and House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, before the 2023 State of the State Address on Jan. 10, 2023, at the Indiana Statehouse. (Credit: Ronni Moore)

About 11 years ago when a vacancy opened on the state Supreme Court, Indiana was one of just a few without a woman serving as a justice.

Loretta Rush, who had been serving as a juvenile court judge in Tippecanoe County, wanted to change that.

"That probably motivated me as much as anything," Rush told State Affairs.

Not only would she soon be appointed to the Indiana Supreme Court in 2012 by former Gov. Mitch Daniels, Rush would also within two years become the chief justice.

Rush is still one of just two female justices out of 111 to have served on the bench. (The other is Myra Selby, who served in the 1990s.)

She is also president of the Conference of Chief Justices and recently represented the United States when she traveled to Finland to meet with justices from other countries to learn about judicial trends across the globe.

As chief justice, Rush holds significant oversight and administration responsibilities for courts across the state.

In a wide-ranging interview with State Affairs, Rush spoke about state lawmakers’ discussion on the constitutional right to bail, why she wants to see more diversionary courts, and her support for expanded assistance for Hoosiers in a mental health crisis.

“What can we do to help stabilize,” said Rush, who has been an attorney or judge for more than 40 years, “and not just keep our jails full of people struggling?”

The conversation is edited for clarity, brevity and length.

Q. You've been on the Indiana Supreme Court for more than a decade. What's different today compared to when you started?

A. There's been a sea change in the last decade. We've gone paperless. We have promoted technology. We have a unified case management system.

So if you want to look up something you can do it on your phone as opposed to getting in your car and going to the courthouse. People can access their court case without having to pay money. It's right at their phone.

We are working a lot with regard to unrepresented litigants. So many of our people are unrepresented. If you go to indianalegalhelp.org, you can access how to navigate guardianships, divorce, expungement, name changes, paternity, just a number of different cases.

Q. Courts can often be mysterious places for people. It seems like a lot of those technology upgrades are meant to remove some of the mystery.

A. Very much so, I think that transparency is important. Our capital is public trust. Are you going to get a fair shake? Are you going to procedurally have a fair hearing? How much is it going to cost? We think about all those things.

Q. Do you find that most people understand the role that the Indiana Supreme Court plays in the administration of courts across the state?

A. No, I don’t think they do. It’s not just deciding cases; you have that administrative engine.

We’re always looking at systems. Do we have enough interpreters? Does everybody understand what’s going on in court?

A lot of people go to court sometimes at their lowest moment. And you want to make sure that the procedural safeguards are there and we’re doing what the constitution requires us to do.

Q. Lawmakers right now are considering an amendment to the Indiana Constitution that would restrict the right to bail. What role do you and the courts play in that public discussion?

A. Under separation of powers, we don’t have a role in that.

But we do have a role procedurally looking at pretrial and pretrial reform. Twenty-five years ago, only 25% of people were in jail on a pretrial basis. Now it's 75%. So we’re really looking at low risk, nonviolent offenders who are poor who need to be able to bond out. We require under Criminal Rule 26 a risk assessment to determine their level of risk.

Bail and bond have always been for two things: One, to make sure that they're not arrested again; and two, to make sure they show up [for court]. So we're trying to meld the constitutional purposes of bail and bond with the practicalities of what's going on in the jail.

Q. In your State of the Judiciary speech, you talked about diversionary or problem-solving courts. You said there’s more work to do. What are the successes and what’s left to do?

A. We’ve tripled them in the last decade. I think we’re growing as fast, per capita, as any other state.

I just want to make sure we don’t have justice by geography. If you live in a county and there’s a problem-solving court, you have that option available to you in lieu of incarceration.

I went to a veterans court graduation down in Floyd County in southern Indiana. Now 10 years later, somebody who would be sitting in the Department of Correction has a company, bought a house, is supporting his family and contributing to his community and he's been clean and sober all this time.

So that extra work at the front end with regard to having a problem-solving court — with accountability, regular court hearings, a team of people working with them — it’s really important. They work.

Our Indiana constitution talks about reformative justice, which means not just punitive, but also reformative. And I think it's a huge part of fulfilling the constitutional charge of redemption, reformation. The idea of people going in and out of jail, in out and of jail, and in and out of jail — something has got to break that cycle. Problem-solving courts have been effective and our judges are really on board.

This year, we've got a legislative ask for them to be funded. And I think we will be able to expand more.

Q. Is the holdup about funding or are there just some counties who are uninterested in participating?

A. I mean, we had a mental health summit last year and, two years before that, we had a substance abuse summit where we invited judges to bring teams from their county. Every county showed up with a team of people to deal with justice-involved individuals who are struggling with addictions and justice-involved individuals who are struggling with serious mental illness. They all came because they really want to see a better result.

When you sit on that bench day in, day out and you're watching some of the pathos that comes before you, there's got to be a better way than just this revolving door. Plus it's a tremendous cost to taxpayers as well. So who can be safely out in the community and who cannot be? It's a tough call and our judges are making those calls every day.

Q. What I’ve learned in Indiana is that any criminal justice reform effort tends to come from an individual county or agency because so much of our system is decentralized. So are there counties or prosecutors' offices, for example, fighting against those problem-solving courts?

A. I'm seeing fewer and fewer of those. Some of the biggest proponents have been prosecutors.

At the substance abuse summit, we had a prosecutor from St. Joseph County come down and say, “Listen, I was skeptical, but now I see it’s working.” And the same thing on pretrial reform with regard to doing risk assessments and determining who can safely be out in their communities.

These are evidence-based, and that's the key. We're not just throwing things at the wall. A lot of these programs and disposition alternatives have been studied to find that they work.

We had to train our judges on the science of addiction. We had to train them on buprenorphine, naloxone, methadone. We brought doctors in, we brought studies in. What is working, what’s not working, for substance use disorder? So that we’re just smarter dealing with criminal actions because when you’re a community it’s not just the one criminal case.

There’s always kids involved. And there’s an employer. And then there’s family members involved. When somebody’s life is spiraling down when they come to court, if you can do something redemptive and put them in a diversion program where they can safely go through treatment, you're not just working on their life.

Q. In your State of the Judiciary speech, you also mentioned Indiana’s 988 crisis hotline. Why is the chief justice putting a spotlight on mental health?

A. It touches almost every docket. And the idea that to have someone to call, someone to answer and somewhere to go in a mental health crisis, and it's not just digging yourself deeper into the criminal justice system. And there are solutions.

I was just on a phone call this morning with the lieutenant governor and with people from the mental health community. I think it's critical. I think the dollars that we spend on incarcerating somebody with mental health, if we could put it more at the front end, I think it would be money better spent with a better outcome for those individuals.

Q. The other big bill along those lines is House Bill 1006, which seems to clarify a lot of the judicial procedures around mental health treatment.

A. It's been a Herculean effort to try to set up a system where they can get assessed and out of the jails and stabilized in lieu of going down the criminal justice route.

I've got to give a lot of credit to the work that Rep. Gregory Steuerwald did on that bill. I mean, he's a lawyer. He's been in courtrooms. He's been in jails.

Q. I’m going to ask the most controversial question of the interview now, and that’s about cameras in the courtrooms. Do you think judges are actually going to allow them?

A. Well, we piloted it with six seasoned judges and they all had them and it worked. It may not be as much as you may want right in the beginning.

We have live streaming of our oral arguments. We live-streamed a lot of trials throughout the state during COVID. The sky didn't fall.

We had two separate pilot programs. It was interesting: The judges were disappointed that more media didn't want to come. There's only two states left in the country that don’t allow cameras in the courtroom.

And so I think there's a level of transparency and public trust that can come by seeing this.

Q. The public perception is that the U.S. Supreme Court is growing more partisan. Does the perception of the U.S. Supreme Court ever concern how your court is perceived?

A. When the National Center for State Courts does a pretty broad survey on trust in government, it's very disappointing to see the trust in government go down. The trust in state courts is higher than the federal courts right now, but the trust in courts is down, but state courts are the most trusted branch of government.

I think you do everything you can to be those neutral arbitrators of the facts that come before you. Protecting the institution of the court is always at the forefront of what I'm thinking so that people think that it isn't going to be based on anything other than the facts and the law.

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: Indiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Loretta Rush chats with President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, and House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, before the 2023 State of the State Address on Jan. 10, 2023, at the Indiana Statehouse. (Credit: Ronni Moore)

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

Who is Jamie Reitenour? Indianapolis mom mobilized volunteers to make governor’s ballot

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is one in a series of profiles of the candidates running for Indiana governor.

ZIONSVILLE, Ind. — It wasn’t the largest campaign event the 2024 election cycle is likely to see.

About 15 people, some of them children, gathered on a rainy April night at Our Place Coffee, nestled just feet from the watchful eye of Zionsville’s Abraham Lincoln mural. But Republican gubernatorial candidate Jamie Reitenour, an Indianapolis mom with no previous political experience, spoke with every single one of them.

It was one part coffee-and-issues politicking and one part informal Bible study, complete with scripture quiz questions for the kids in attendance.

Reitenour, well-worn Bible in hand, shared her oft-repeated story of being called by God to run for governor about six years ago — a destiny confirmed by friends and strangers alike along the way, she said. This charge, she told the group, would allow her to rise above traditional campaign currency, such as fundraising dollars and polling numbers.

Suzanne and Shon Hough sponsored the event after meeting Reitenour at their shared church, Horizon Christian Fellowship in Lawrence.

“As soon as we met her, we knew this is someone to support,” Suzanne Hough said. “We knew she wasn’t a politician. She was called. She has a love and compassion for people.”

That is how Reitenour has made it this far — how she gathered the 4,500 state-mandated signatures to qualify for the May 7 primary ballot, how she’s made it onto a stage filled with more experienced and wealthier opponents. For more than a year, she’s hosted several small events per week throughout the state, traveling some 35,000 miles, by her count.

The dozen or so latte-sipping supporters had a part to play, the candidate said.

“Go to your contact lists and tell them about our Facebook,” Reitenour said. “We could reach 144 people today if we all did that.”

The call

Reitenour’s purpose changed in 2017 while walking through downtown Indianapolis with her husband, Nathan.

“I just heard a whisper: You’re going to be the governor of Indiana,” Reitenour told State Affairs.

The couple wandered over to the governor’s mansion.

“We looked at it and thought, ‘That does not look like our family,’” she recalled. “So I just put the calling on the shelf.”

Indiana requires gubernatorial candidates to have lived in the state for at least five years. She had only just moved from Michigan.

Reitenour believed the country was in a good spot under then-President Donald Trump. Why would she need to run?

“I just thought about it,” Reitenour said. “Why would the Lord call an ordinary person to something like that when the nation was doing so well? But the reality of scripture is that you see these times where people are called, and you can see the reasons for the calling around them.”

Her regular Bible contemplation soon took her to the Book of Nehemiah, who was a governor. Another sign, she said.

The state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic set off alarm bells for Reitenour, who considered steps like mask requirements an affront to personal liberty. She brings up the subject often, and it made it into her coffeehouse remarks.

“How am I in a conservative state, but I don’t feel free?” she told the crowd.

After COVID-19 and the election of President Joe Biden, Reitenour began to think more seriously about running for governor.

Her mission was affirmed first by a close friend, whom Reitenour said received a similar calling from God to help her candidacy, and then by strangers, whom she said confirmed her destiny during separate chance meetings at a Panera Bread location.

She began to meet with church groups and advocacy organizations that align with her views, including Moms for Liberty and Indiana Right to Life. Despite being referred to as an activist on the campaign trail, Reitenour said she is not part of any activism group.

Getting on the ballot

This network of like-minded supporters would soon serve as the volunteer arm of Reitenour’s campaign.

Indiana requires candidates for governor to collect at least 4,500 signatures from voters, including at least 500 from each of the state’s nine congressional districts. It’s a tall order even for seasoned politicians, who often hire specialized operatives for the task.

“The mystery of how we did that will also be the mystery of how we win,” Reitenour said.

She focused on growing supporters and gathering signatures at each small event she hosted, then mobilizing those attendees to gather still more for her.

“I had a formula in my heart for this that the Lord gave me at 4 a.m. one morning,” she said.

The campaign

Reitenour made the ballot, but she is the least-known candidate in a field that includes Sen. Mike Braun, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, former state Attorney General Curtis Hill, former state Secretary of Commerce Brad Chambers and Eric Doden, a Fort Wayne businessman and previous president of the Indiana Economic Development Corp.

She has no previous political experience. She is a stay-at-home mom who also homeschools her five children and volunteers through ministry. Her previous work experience includes compliance management at a mortgage company, secretarial work and even a stint as an assistant coach in women’s field hockey.

Reitenour was selected in the governor’s race by just 2% of respondents in a recent State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana poll, tying her with Hill for last place behind front-runner Braun (44%). She has consistently polled in the low single digits.

While other gubernatorial candidates can draw from years of campaign fundraising experience or millions in personal finances, Reitenour had raised just a little more than $54,000 as of March 31.

She has thus found herself paddling in a proverbial ocean of campaign spending.

The four top-polling candidates — Braun, Chambers, Doden and Crouch — have spent a combined $20 million.

After participating in the first gubernatorial debate on March 11, Reitenour did not qualify for a March 27 debate hosted by WISH-TV due to her fundraising numbers, as the television station required candidates to have raised $300,000 by December.

She was also excluded from a March 26 Fox59/CBS4 debate for not reaching a 5% polling threshold. She will be included in the final April 23 debate, hosted by the Indiana Debate Commission.

Reitenour has campaigned using a constantly shuffling group of volunteers. She has only one full-time employee: campaign assistant Casey Pierce, who met Reitenour through his mother’s church.

“It just felt like the right thing to do,” Pierce said of joining the campaign. He has never worked in politics before.

Pierce called his initial meeting with Reitenour “a Holy Spirit encounter.”

Reitenour’s platform

Reitenour described education as the state’s “greatest vulnerability,” and thus her primary platform.

“The next generation is not being educated well, and this has been a long time coming,” Reitenour said.

She has received guidance from the Hamilton County chapter of Moms for Liberty, which made national headlines in 2023 after using a quote attributed to Adolf Hitler in its first newsletter. The nonprofit, which pushes against socially minded education reforms like critical race theory, subsequently apologized.

Reitenour likewise opposes ideas like social-emotional learning in classrooms. Her plan also proposes removing technology from grades K-5, calling for private businesses to sponsor classrooms and requiring all students to pursue an apprenticeship before high school graduation.

She also favors an audit of the Indiana Economic Development Corp., tax cuts, a focus on investing in small towns and generally “pointing Indiana in the direction of family.”

The future

At her coffee shop appearance, Reitenour shied away from admitting her long odds in the race.

“The political system is meant to squeeze people out, but I am working against it,” she said.

She pledged to continue organizing no matter the primary election results.

About Reitenour

- Age: 44

- Hometown: Indianapolis

- Education: Psychology degree from Missouri State University

- Family: Married to Nathan Reitenour, with five children, ages 13, 11, 10, 9 and 4

- Job: Stay-at-home mom, homeschool teacher

- Work history: Former compliance manager at Windsor Capital Mortgage, former athletic director at Calvary Christian School (at Calvary Chapel Vista church in California)

Read these related stories

- Eric Doden is running from behind but hopes his ‘bold vision’ will propel him forward

- Suzanne Crouch positions herself as a ‘different’ candidate for the voiceless

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Child care: Where Republican candidates for governor stand

Six candidates are seeking the Republican nomination for Indiana governor in the May 7 primary. State Affairs is providing looks at their stances on several issues. Jennifer McCormick is unopposed for the Democratic nomination.

Indiana’s high cost of child care ranks as a primary concern for many of the state’s families.

According to Child Care Aware of America, a nonprofit organization that studies child care costs, Indiana ranks as the eighth most expensive state for infant and toddler care. The cost for caring for a baby averages 14.5% of a family’s median income, while toddler care is 12.9%.

Only 5% of Indiana families can afford infant care, the Economic Policy Institute found.

State Affairs asked each of the six Republicans vying for Indiana governor — U.S. Sen. Mike Braun, former state Secretary of Commerce Brad Chambers, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, Fort Wayne businessman Eric Doden, former state Attorney General Curtis Hill and Indianapolis mother Jamie Reitenour — how they would lower Indiana families’ child care costs if elected.

Here are their responses.

Mike Braun

“The high cost of child care burdens Hoosier families and businesses, who are trying to recruit and retain the best workers. As governor, I am open to and will work on solutions that will reduce the cost of child care, which is a win for our economy and families.”

Brad Chambers

“As governor, I’ll explore strategic expansions of all-day pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds, including potentially increasing the income eligibility level for state-funded pre-K programs. I’ll create a state-level child care tax credit that requires recipients to work to be eligible to receive it.”

Chambers said he would also explore incentives for employer-sponsored child care.

Suzanne Crouch

“First, I would lead the effort to eliminate the state’s individual income tax, which will mean more money in families’ pockets and help reduce the financial strain of child care expenses … As governor, I would propose that the General Assembly put a priority on early childhood education throughout Indiana.”

Crouch would also support the expansion of at-home and religious-based child care, she said, noting Indiana has “some of the highest relative child care costs in the country.”

Eric Doden

“I’ve offered a bold plan to expand pre-K access to every community in the state. By partnering with communities, nonprofits and education partners, we will begin addressing this important need. … We need a state with thriving communities and access to opportunity. Cost of child care concerns are downstream of family formation rates, good-paying jobs, home ownership and a host of other economic and community issues.”

Curtis Hill

“The government is not responsible for providing child care for private sector employees. Its responsibility is to dismantle the licensing and regulatory burden that prohibits new child care providers from entering the market. If we want to lower the cost of child care, we must cut the government regulations forcing child care facilities to either close or raise prices to meet unnecessary government requirements.”

Jamie Reitenour

“We cannot bear down on taxpayers for everything. We just cannot do it. But we can talk to the private sector and reason together. Can we have in-house day cares at offices? Yes. Can we have employers operate growth centers for employees’ kids? Yes. Taxpayers are not the answer; the private sector is. With competition for qualified workers, larger businesses already employ creative benefits, including child care assistance, to attract talent.”

Read these related stories:

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Poll finds Holcomb popular among Republicans even as potential successors keep distance

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb remains popular among Republicans, according to a State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana poll, even as the GOP candidates to take his place have kept their political distance from him. The polling results released Thursday show Holcomb with an overall positive job-approval rating of 69% among self-identified Republicans and Republican-leaning independents. The results …

‘It’s sort of a blowout’: Braun holds commanding lead in ‘State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana’ poll

U.S. Sen. Mike Braun holds a commanding lead in a new State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana poll of likely Hoosier Republican voters in the May 7 gubernatorial primary. Asked who they would vote for if the primary were held today, 44% of respondents picked Braun. Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch trailed with 10% of the vote, and …