Living behind the eight ball: Rural Georgians fight long health care odds

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories looking at the lack of health care in areas of rural Georgia and how providers and lawmakers are dealing with the issue.

Walker County resident Angela Pence’s contractions were three minutes apart when she and husband Dan drove 30 minutes to a hospital in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where their daughter was born last December. Five of her nine children, aged 5 months to 13 years, were born in Chattanooga.

“Up here where I’m at, there is no other option other than going across the line to Tennessee,” said Pence, who lives in the northwest Georgia mountain town of Chickamauga, population 3,070. To have her baby in Georgia, “I would have had to go an hour south.”

With no OB-GYN and one pediatrician in Walker County, Pence has to go to nearby Catoosa County for those basic health care services. There also are no emergency medical doctors in Walker County, home to about 69,000 mostly white residents and the famed tourist attraction Lookout Mountain.

“I would really love to see them put an emphasis on maternal health. Georgia has some of the worst maternal health in the United States,” Pence said. “I would really love to see that change and if they [lawmakers] can’t change it, then they really need to allow midwives and doulas to practice.”

Eighteen of Georgia’s 159 counties have no family medicine doctor, according to Kyle Wingfield, president and CEO of Georgia Public Policy Foundation and author of “Addressing Georgia’s Healthcare Shortage.”

Some 65 counties have no pediatrician; 82 counties don’t have an OB-GYN; 40 counties have no internal medicine doctor; and 90 counties don’t have a psychiatrist, according to the Georgia Department of Community Health.

Meanwhile, rural Georgia’s health care challenges aren’t lost on state lawmakers.

Health and human services is the second-largest expense for the state, accounting for about 24%, or $7.8 billion, of Georgia’s $32.4 billion fiscal year 2024 budget.

Yet health care bore the brunt of Gov. Brian Kemp’s recent vetoes and disregards in the signed fiscal year 2024 budget. Of the roughly $255 million in Kemp’s non-binding budget disregards and line-item vetoes, the majority of those cuts will reduce funding for health and education programs and services, the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI) said in a report released this week. The total number of vetoes and disregards involving health care alone amounts to over $104 million, or 41% overall.

“These actions will withhold tens of millions from the state’s ailing health care system and safety net,” noted Danny Kanso, GBPI’s director of legislative strategy and senior fiscal analyst and author of the report.

While Republican and Democratic lawmakers agree that Georgia’s rural health care system needs fixing, they can’t seem to agree on how to fix it.

Have doctor, will travel

Access to reliable health care in Georgia largely depends on where you live.

If you are one of the 2.75 million people living in rural or medically-underserved Georgia, you already know you’re living in a medical desert.

Over the last 20 years, the state’s population has shifted to bigger towns or metro areas. Roughly 6 in 10 Georgians live in the 29 counties in and around Atlanta, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 population data.

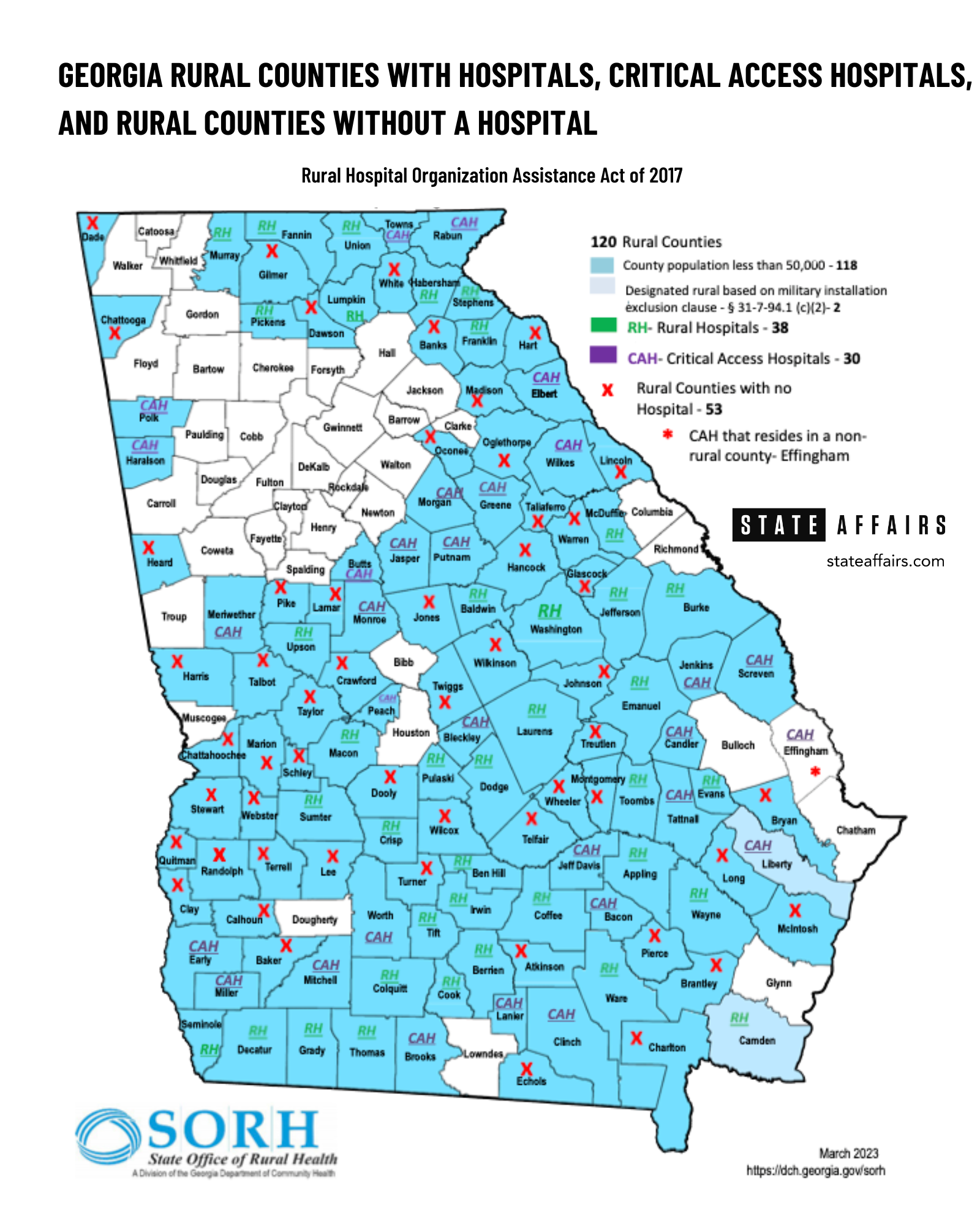

The population shift has meant rural communities such as Echols County (population 3,699), Heard County (population 11,565) and Webster County (population 2,372) have to contend with no hospital or federally qualified health center. According to the State Office of Rural Health, a division of the Georgia Department of Community Health, there are a total of 59 hospitals across 120 counties in the state classified as rural.

A sudden, severe illness or even routine checkups can mean traveling hours and miles to a doctor or hospital.

In some cases, hospitals have grown out of this need, like Wills Memorial Hospital in Washington, Georgia. The 25-bed, recently renovated acute care hospital, which also offers outpatient and routine medical resources, serves primarily Taliaferro, Wilkes and Lincoln counties, with a total population of about 18,820, according to the 2021 U.S. Census.

“The two major questions that they ask when a company looks at your area is what is the healthcare and what is the education?” said Chuck Harris, commissioner in Catoosa County, which plans to break ground this summer on a state-of-the-art hospital that will also serve Walker and Dade counties. “We’ve got a first-class school system and we wanted a first-class hospital that would match that.” The hospital is slated to open in three years, Harris said.

Shortages, the uninsured, the perfect storm

Meanwhile, some 280 miles southwest, Dr. Karen Kinsell is the lone doctor in Clay County, one of the poorest counties in the state, with a population of 2,882. She sees between 30 and 40 patients four days a week, many from surrounding counties and Alabama.

“We’re still doing a fair amount of virtual [appointments] partly because it’s such a rural area that it really is more convenient for a lot of folks,” Kinsell told State Affairs. “When we say telemedicine, we mean telephone because most people don’t either have the hardware or enough [Wi-Fi] signal to make a video.”

Kinsell’s biggest concern is people’s inability to pay for health care. “This is a very poor area. People are uninsured,” she said.

Clay County is mostly blue-collar, retired or disabled. It’s 60% Black and 40% white, and the 2021 U.S. Census reported a median household income of $35,893. There’s a school that goes up to the eighth grade and a nursing home. For those able to work, there’s a chicken factory across the line in Alabama, said Kinsell, who works out of a former Tastee-Freez fast food restaurant that’s been remodeled.

The nearest hospital is 20 miles away.

Clay also has a physician assistant but PAs often are limited in what they can do. Georgia law prohibits PAs and APRNs — which include nurse practitioners, certified nurse-midwives, clinical nurse specialists and certified registered nurse anesthetists — from performing the entire scope of practice for which they are trained. Georgia laws also require more supervision by a physician than many other states require.

Kinsell charges $10 and if they can’t pay, “we see them anyway if they’re uninsured. So people will drive 40 miles for that. They can’t afford to go elsewhere. This is terrible, but that’s how things are in America.”

Kinsell has been in Clay since 1998, working part-time jobs at the prison and at urgent care centers to help keep her practice going.“I’m trying to work 26, 27 days a month and that’s probably not sustainable,” said Kinsell, 68.

Kinsell’s story is what makes health care in rural Georgia “pretty dire,” University of Georgia political science professor Charles Bullock told State Affairs. “In a way, it’s kind of turning the clock back to what it was like pre-Medicaid/Medicare.

“You just didn’t have public programs that were designed to help people who couldn’t pay in cash for the service,” Bullock said. “Lots of doctors in small towns simply provided free care. They knew the poor family couldn’t pay or maybe you heard the stories about poor families paying by bringing produce.”

Among the most visible signs of rural Georgia’s health care challenges is what’s not there anymore, Bullock said.

Rural hospital closings since 2013

| Hospital | Location | Beds | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northridge Medical Center | Commerce County | 27 | 2020 |

| Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center | Randolph County | 25 | 2020 |

| Chestatee Regional Hospital | Lumpkin County | 49 | 2018 |

| North Georgia Medical Center | Gilmer County | 140 | 2016 |

| Lower Oconee Community Hospital | Wheeler County | 25 | 2014 |

| Calhoun Memorial Hospital | Calhoun County | 25 | 2013 |

| Stewart-Webster Hospital | Stewart County | 25 | 2013 |

| Charlton Memorial Hospital | Charlton County | 15 | 2013 |

Eight rural hospitals have closed in Georgia over the last decade. Another 19, or 28%, are at risk of closing, according to the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform.

Like other states, Georgia struggles with health care worker shortages. All told, the state needs more than 60,000 doctors, nurses and other health care personnel, many for rural communities, according to a final report issued last year by the Georgia Healthcare Workforce Commission. The commission was created in 2022 by Gov. Brian Kemp to deal with the state’s ongoing health care worker shortage.

About 1.4 million Georgians, 13.7% of the population, have no health insurance, the third-highest uninsured rate in the nation. GBPI projects the uninsured rate in rural Georgia could climb to more than 25% by 2026.

And just as Georgia is putting the COVID pandemic in the rearview mirror, it is now having to deal with more administrative challenges. The state is in the midst of reviewing its eligibility list of Medicaid recipients and introducing a work-for-Medicaid program which starts next month. Millions of Georgians’ lives are expected to be upended.

“That’s a perfect storm for a health care disaster,” said Jimmy Lewis, chief executive of Hometown Health LLC, an advocacy network of rural hospitals in the Southeast.

Location, location, location

If you live in rural Georgia, your life expectancy is lower than those living in metro areas of the state. Life behind the health care eight ball begins at birth — if you make it out of the delivery room and through the first few months of life.

At one point, half of the 130,000 babies born in Georgia each year were born in rural Georgia where fetal mortality rates are higher: 8.3 deaths per 1,000 live births vs. 7.6 for metro residents.

Experts say rural Georgians tend to smoke more and have more instances of diabetes and other chronic conditions. Death rates are higher due to heart disease, stroke, cancer and car crashes.

Consider this: Residents in Forsyth County, a metro Atlanta enclave where the median household income is about $121,000 a year and the poverty rate is 5%, live nearly 13 years longer than people in the southwest farming county of Miller, according to Georgians for a Healthy Future. The median household income in Miller is slightly less than $52,000 a year. Nearly 1 in 5 live in poverty and 15% don’t have adequate access to food.

“There’s a high-risk patient outside of the wealthy zip codes,” said Monty Veazey, president and CEO of the Georgia Alliance of Community Hospitals. (Read our Q&A with Veazey here.)

Health Care in Georgia: By the Numbers

- Georgia population: 10.5 million*

- Georgia residents in non-metro areas: 1.8 million, or 17.1%*

- Number of doctors statewide: 24,914

- Average hours worked: 44

- County with the most doctors: Fulton, with 5,438

- Fulton County population: 1.06 million**

- Rural counties: 120

- Counties with no hospitals: 53

- Hospitals in rural counties: 59

- Rural health clinics: 85

- Federally-qualified health centers: 35 with 294 sites in 126 counties

- Counties with no doctors: 9

- Total population of the counties with no doctor: 50,817**

- Counties with no family medicine physician: 18

- Counties without an internal medicine physician: 40

- Counties with no pediatrician: 65

- Counties with no OB-GYN: 82

- Counties with no emergency medicine physician: 73

- Counties with no general surgery physician: 80

- Counties with no psychiatrist: 90

- Primary care physicians needed in Georgia: about 700

- Rural hospital closings since 2013: 8

- Average per capita income for metropolitan residents in 2020: $51, 780

- Average per capita income for rural residents in 2020: $38,513

- Urban poverty rate: 13.1%

- Rural poverty rate: 18.8%

- *U.S. Census ACS 2020 estimate **2021 census

- Note: Some health-specific data is for 2019 and 2020 and are the latest available data.

- Sources: Georgia Board of Health Care Workforce, 2020; KFF, September 2022; Georgia Hospital Association, 2023; State Office of Rural Health; Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform; Rural Health Information Hub

The rural problems exist in a state that already nationally ranks poorly, healthwise.

Georgia ranks 46th in child health, 49th in maternal mortality [Black women in Georgia have the highest maternal mortality rate in the country] and 47th in access to mental health care, according to the GBPI.

Cash-strapped rural hospitals are taking care of patients, many of whom are indigent. And the emergency rooms have become de facto primary care facilities.

“We’ve seen people who were pregnant and bleeding. We see people who are involved in car accidents. We see gunshot victims. We see a lot of cases of people just realizing they’re pregnant. We see people who come in and are being diagnosed [in the ER] with cancer for the first time,” Dr. Andre Johnson, an emergency room physician at Fairview Park Hospital in Dublin, told State Affairs.

Johnson recalled a case in January where he informed a patient they had fourth-stage cancer and should see a cancer specialist. The patient returned to the ER two months later complaining of the same pain, yet hadn’t seen the cancer specialist. Johnson also noted that it is not unusual for some pregnant women to use the emergency room as their main source of prenatal care.

Johnson’s assessment is backed by a report by the Georgians for a Health Future released last September. It found 62% — 3 in 5 people — who live in east Georgia, where Dublin is located, delayed or went without needed health care during the past year due to health costs. That was the highest rate in the state.

At 71%, east Georgians also rank highest in the state of people who struggled with “affordability burdens” in the last year, the report noted.

More than half, 57%, of that region’s residents said the health care system needs to change.

Johnson is an independent contractor who works five to six days a week at the 190-bed acute care Fairview Park Hospital, which draws patients within a two-hour radius. He said he sees anywhere from 100 to 120 patients a week during his 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. shift.

“You would think a small place like Dublin wouldn’t see so much pathology or many life-threatening things going on,” Johnson said. “Because when you think of large facilities like Emory or Grady, you think about all of these different medical problems and serious conditions that people have. But this small place — and most small places — are the first facilities and staff to see people with very, very complicated medical problems like Stage 4 cancer that need specialists. But the first person to see them are people like us.”

“It’s not always as simple as saying ‘let’s direct funds here or there’,” Johnson said. “Sometimes you have to think about what’s behind what’s causing some of the things that are stressing the medical community.”

Help may be on the way

Kemp created the Healthcare Workforce Commission last year to deal with continuing shortages in the profession.

“I don’t think any of us are satisfied with where we are. Everybody I know is working trying to improve it,” state Rep. Butch Parrish, R-Swainsboro, told State Affairs.

Parrish was appointed earlier this year by House Speaker Jon Burns to chair the House Special Committee on Health Care, which was established by Burns. Parrish has chaired the appropriations subcommittee which deals with health care spending and was recently appointed to chair the House Study Committee on Certificate of Need Modernization.

“We’ve been doing a lot [on health care],” Parrish said. “But sometimes we go in different directions in trying to provide the services. What we’re trying to do now is coordinate [various efforts] so that we can get the biggest bang for our buck and have us all moving and pulling in the same direction.

“Healthcare is a complex issue,” he added. “It’s not a simple two-plus-two-is-four kind of program. If it were that simple, we’d have had this issue solved a long time ago. But it involves a lot of people and a lot of different complex issues. So we’re going to continue to work on it and see what we can do to improve access to quality, affordable health care for everybody in this state.”

In similar fashion, Lt. Gov. Burt Jones earlier this year appointed the Senate Study Committee on Certificate of Need (CON) Reform, which met this week.

The study committees couldn’t have come at a better time.

Created in 1979, the CON program was intended to reduce duplication of services by regulating where hospitals are built. Over time, however, it has become a controversial sticking point — some would say a barrier — to making affordable health care accessible throughout Georgia. Many say the 44-year-old program needs to be overhauled or scrapped altogether.

In fact, Georgia would be better off without CON, Dr. Thomas Stratmann of George Mason University told the committee at its first meeting Tuesday.

Stratmann, one of three experts who spoke before the committee, co-authored a study that compared 35 states with CON laws with 15 states that don’t have CON laws.

The results showed “that CON laws reduce health care quality, reduce access to health care, and harm patients by reducing the availability of medical equipment such as MRI machines that can help diagnose illnesses and prevent premature deaths,” added Stratman, professor of economics and law at George Mason and senior research fellow at the university’s Mercatus Center.

“The justification [for CON when it was created] was to maintain medical costs; however, studies showed that theory was not successful in containing costs,” he said.

Committee member Sen. Freddie Powell Sims represents 13 southwest Georgia counties, most of which are rural with poor residents often lacking insurance. As rural hospitals have continued to close in the area, Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital in Albany has become the key source of health care in the region.

Sims said she wants to make sure that whatever changes are made to the state’s CON laws, it creates a “level playing field for our local hospitals that are still open in rural Georgia. Most of them have closed and they’ve closed simply because nobody’s there to support them. There’s not enough population.

“That’s why you have people driving in,” she noted. “On any given day, you can walk through the [Phoebe Putney] parking lot and you will see the tags of cars from at least 26 to 30 different counties, and they’re coming in from Alabama and Florida.

“Most folks don’t understand that we can build a hospital in your community if your taxpayers who are there can afford it. Do you have the taxpayers who can keep it open? “said Sims. “Because the state is not going to pay for you to have a hospital. You must have the population to support and sustain it.”

While state lawmakers try to figure out what to do with CON, they’re moving ahead with other initiatives to address health care in rural Georgia, including:

- More broadband. Just this week, Kemp announced $15 million in grants to expand high-speed internet and improve internet connectivity in four south Georgia counties, a move that will put health care services such as telemedicine within reach of more rural Georgians. [Walker County received a $6.2 million grant last year to improve its internet infrastructure and bring gig-speed fiber optic internet to over 2,600 residents who didn’t have the service. It’s set to be finished in December 2024, Walker CEO Shannon Whitfield told State Affairs. “That will help with telemedicine. It’s going to take them from the Dark Age to gig speed.”]

- More pediatricians. In February, Kemp announced a $200 million initiative between Children’s Health Care of Atlanta and the Mercer University School of Medicine to address the shortage of pediatricians in rural Georgia. The money will pay for 10 full-tuition scholarships for pediatrics students who agree to practice in rural Georgia for at least four years after residency training.

- More medical grads from overseas. Over the last decade, Georgia has placed 289 primary care and specialty health care doctors in 41 counties through its J1 Visa Waiver Program. Nineteen of those counties were considered rural.

- Loan repayment programs. With the average medical school graduate finishing with $275,000 in debt, the ability to get up to $100,000 to help with loan repayment is significant. The Georgia Board of Health Care Workforce administers loan repayment programs for physicians, dentists, advanced practice nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. They must work in a county with a population of less than 50,000 and commit to a year. They can get the award up to four times with annual applications. Physicians and dentists can get $25,000 a year. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants can earn $10,000 a year each.

- Rural Hospital Stabilization program. This annual program gives grants to rural hospitals. The state awarded $9 million total this year to 10 rural hospitals. The program is in its seventh year.

- Other funding. In April, the state received final approval of more $100 million redirected to help rural hospitals. The reallocation is from the Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital payment intended to offset hospitals’ uncompensated care costs to improve access for Medicaid and uninsured patients.

Meanwhile, the days of crossing state lines for hospital services may end for residents in the northwest Georgia mountain counties of Catoosa, Dade and Walker.

CHI Memorial plans to break ground this summer on a 60-bed, start-of-the-art hospital in Ringgold. The “smart” hospital will have an ICU, emergency room and operating rooms.

The hospital had been at the center of a longstanding feud between CHI and Parkridge Hospital in Tennessee. Parkridge opposed CHI’s Certificate of Need to build the hospital but relented late last year after Kemp and other Georgia lawmakers intervened, allowing plans for the hospital to proceed.

The hospital comes as a $200 million resort is taking shape atop Walker’s Lookout Mountain, Whitfield said. It’s set to open next spring.

Read what a veteran lobbyist says about the state of health care in rural Georgia here.

Have questions, comments or tips? Contact Tammy Joyner on Twitter @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @stateaffairsUS

Instagram@stateaffairsGA

LinkedIn @stateaffairs