Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoLawmakers, hospitals hustle to find cure for growing nurse shortage

Becoming a nurse amounted to baptism by fire for Patrick Umeibe. The registered nurse entered the profession in March 2020 — just as COVID-19 officially hit. He has been juggling hefty patient loads and long hours ever since.

Three years in, “I still have charcoal burns on my arm,” the Atlanta registered nurse (RN) quipped. The pandemic and demand for nurses fast-tracked his career. He became a traveling nurse after a year in the field. Normally it takes two years.

Traveling, or contract, nurses are not attached to a particular hospital and work temporarily at various locations.

In Augusta, nurses at the Charlie Norwood Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center also are logging long hours, including mandatory overtime, and increasingly taking on more patients because there are not enough nurses.

“They’re tired,” said Irma Westmoreland, a registered nurse at the VA Hospital who teaches nurses how to use the hospital’s computerized charting and documentation system. The hospital also is struggling to keep nurses. It hired 23 nurses between January and March of this year. During that same time, 22 nurses — including two new hires — left.

“It is really exhausting for nurses right now. Workloads have gotten heavier. Every service has gotten leaner and leaner,” Westmoreland said. An RN since 1986, she has worked in about every area of nursing: the intensive care unit, emergency room and acute care.

“We had a lot more nurses and things for our patients [back then] than we have right now.”

Welcome to nursing, post-COVID.

While the urgency of the pandemic appears to have subsided, the nursing shortage and its accompanying challenges haven’t. Georgia nursing officials, schools and hospitals are trying to address the shortage with signing bonuses and school-to-hospital partnerships.

Georgia’s nursing shortage hasn’t escaped state lawmakers. Health and human services is the second largest expense for the state, accounting for about 24%, or $7.8 billion, of the state’s $32.4 billion fiscal year 2024 budget. Gov. Brian Kemp last week signed legislation that includes funding for several bills passed during this legislative session to help ease financial burdens for nurses and nursing school instructors in an effort to attract and keep nurses.

“We do need more nurses. The pandemic really pointed that out. We were able to put money in the budget,” State Rep. Butch Parrish, R-Swainsboro, told State Affairs. Parrish chaired the Special Committee on Health Care, formed this past session to coordinate all legislative efforts in the House to help address health care issues.

Georgia is projected to have the sixth-worst shortage of registered nurses in the country by 2030, according to the Bureau of Health Workforce.

More than 100,000 registered nurses nationwide were estimated to have left the field during the pandemic, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Another 800,000 RNs are expected to leave over the next five years. And for the first time in 20 years, enrollment in entry-level baccalaureate nursing programs fell 1.4% last year, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, raising concerns over future staffing and patient care and safety.

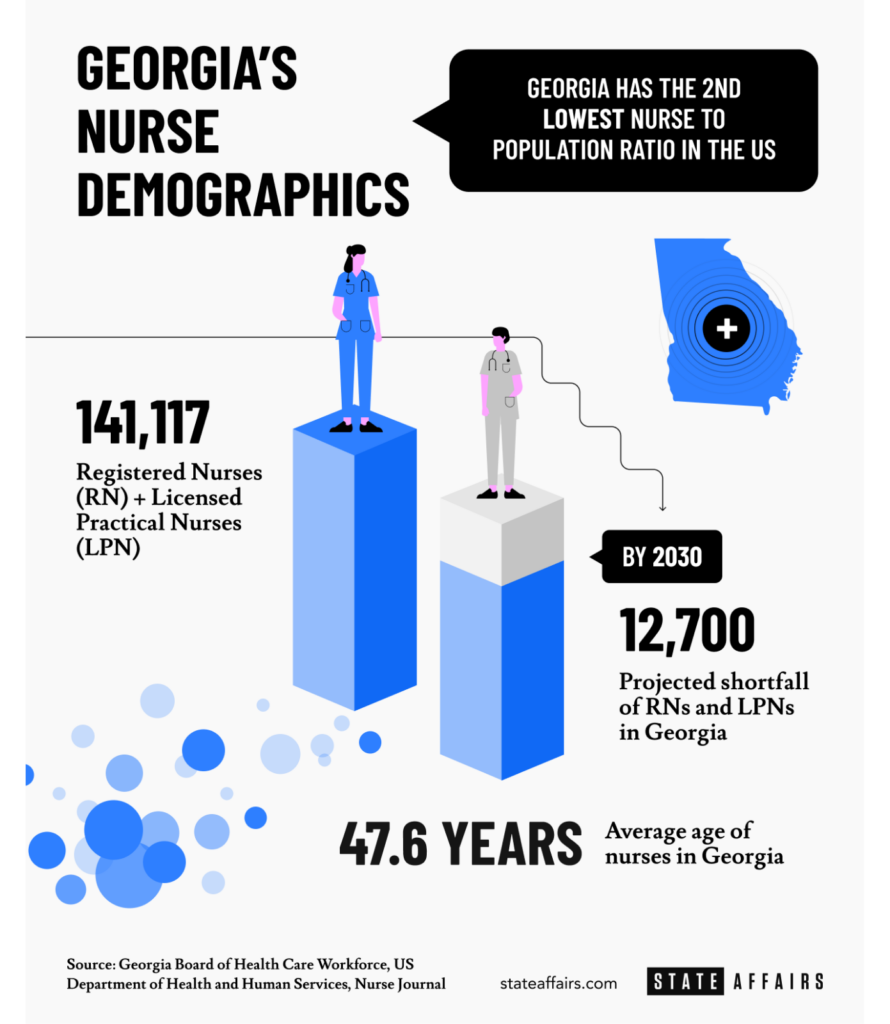

Here in Georgia, there are 141,117 actively-licensed nurses, according to the Georgia Board of Health Care Workforce’s nursing data. That data includes RNs, nurse practitioners, licensed practical nurses and others. Nine in 10 nurses in the state are women.

Meanwhile, the state’s population is aging. So is the nursing field. The average age of a Georgia nurse is 48. The head of one nurses’ group attributed the nursing exodus and ongoing shortage to “stress and the burnout from the pandemic.”

“I’ve talked with some [nurses who] were working two, three straight weeks of 12-hour shifts without a break,” Dina Hewett, president of the Georgia Nurses Association (GNA), told State Affairs. “Some nurses might be pulled into the critical care area where we’ve had a lot of these COVID patients because they had to be on the ventilator. So what we would consider a floor nurse might have to float into a critical care area, serving as an extra set of hands. So, they’re working in an area they’re not familiar with. That adds a lot of stress and anxiety.”

Even though the COVID emergency has died down, nurses now are caring for patients who put off preventative care visits during the pandemic, or who were made to wait because of overflowing hospitals.

“[It’s those patients] who didn’t go get that mole checked who now have cancer, who didn’t get their followup (checkups) or surgeries, other things they needed because all of the care was being given to the urgent patient who was in the facility,” Westmoreland said.

Georgia’s patient-nurse ratio remains exhaustive. The state has about 7.31 nurses for every 1,000 people, the second-worst ratio in the country behind Utah, according to NurseJournal. The national average is 9.19. By comparison, South Dakota and the District of Columbia had the best ratio at 15.95 and 16.74, respectively.

Best-paying Georgia cities/counties for nurses (annual)

- Roswell: $80,760

- Gainesville: $73,820

- Dalton: $73,790

- Clarke County: $73,370

- Richmond County: $72,420

- Savannah: $71,450

- Rome: $70,320

- Albany: $69,670

- Warner Robins: $68,510

- Columbus: $68,330

While experts continue to mull over the national nursing shortage, Westmoreland said: “There really isn’t a shortage of nurses. There’s a shortage of nurses willing to work in the conditions at the bedside.”

In 2022, there were more than 1 million licensed registered nurses who were not working as RNs, according to National Nurses United (NNU), which analyzed data from the National Council of State Boards of Nursing and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In Georgia, about 45,000 active RN licenses currently aren’t being used, according to NNU’s research.

This week during National Nurses Week, State Affairs spoke with several nurses in addition to Westmoreland who talked about working in environments where:

- Many hospital floors increasingly are now staffed with traveling nurses because hospitals don’t have enough or have lost regular staff nurses. Nurses are having to be responsible for more patients than usual. For example, an ICU nurse usually has two patients. However, during COVID, it was not unusual, the nurses said, for a nurse to end up with double the number of patients during a shift.

- Charge nurses who normally supervise a floor now have to take on patients along with their supervisory duties.

- Early-career nurses — those who’ve been in the field less than 10 years — report feeling burned out.

- Nurses are dealing with potentially dangerous patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal, dementia or other problems.

The nurses interviewed for this story said the patient load has improved. “It definitely is better but we still need staff ratios so we can keep nurses,” Westmoreland said, adding she’d like to see Congress pass legislation that would set national safety standards for nurse staffing in hospitals.

Currently, there are no federal mandates regulating the number of patients a registered nurse can care for at one time in U.S. hospitals. Two bills — S. 1113 and H.R. 2530 — introduced earlier this year would address those concerns, according to the nursing union National Nurses United.

Georgia at any given time is in need of thousands of nurses, with the greatest need being in metro Atlanta. Between June 2021 and May 2022, for example, there were more than 10,000 job postings for RNs in the Atlanta area at health facilities such as Piedmont, WellStar, Emory and Northstar, Hewett said.

Many of those jobs are being filled by traveling nurses like Umeibe and Alex Todd.

“I’ve definitely seen the shortage,” said 30-year-old Todd, who has worked at several metro Atlanta hospitals as well as a hospital in Columbus. During his most recent traveling assignment, he said he worked with quite a few other traveling nurses.

The increased presence of traveling nurses, also known as contract nurses, has created some tension, Hewett concedes.

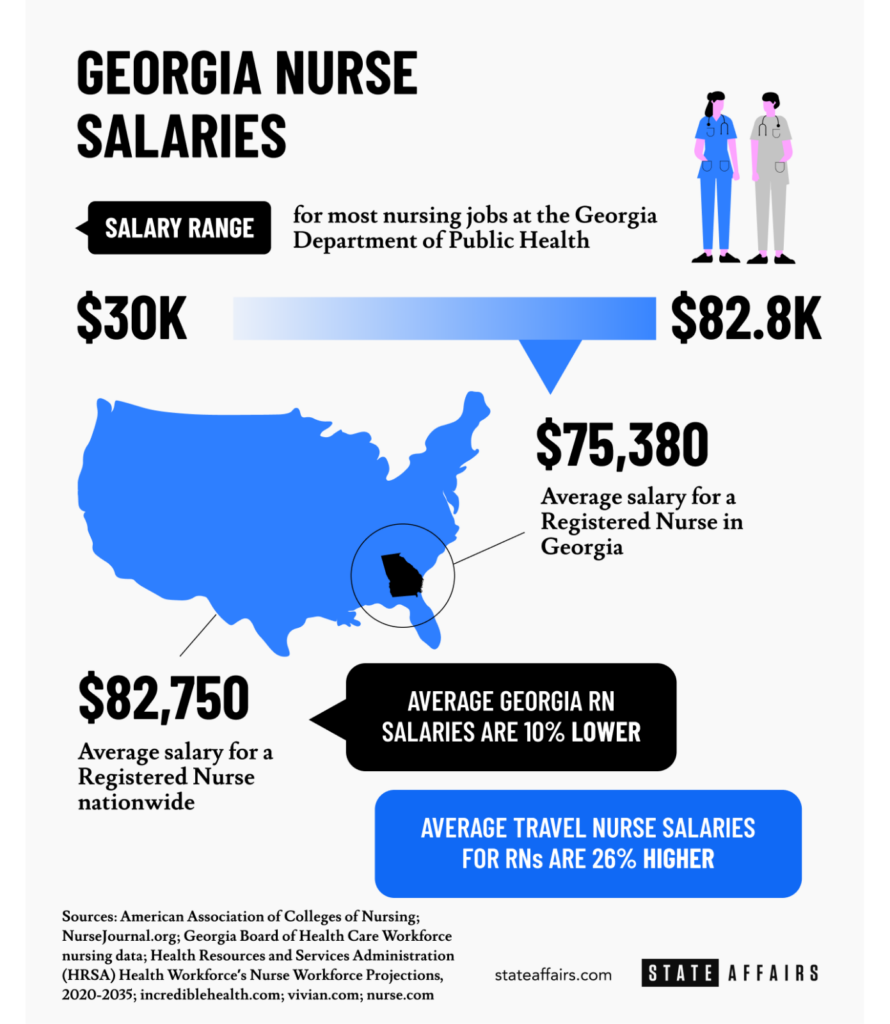

Registered nurses in Georgia earn, on average, $75,380 a year or $36.24 an hour, 8% below the national annual average of $82,750, according to incrediblehealth.com. Travel nurses fare best when it comes to pay. They earn an estimated 30% more than registered nurses on average, according to NurseJournal.

“We’re trying to address that by improving the work environment and conditions for the hospital-employed nurses,” Hewett said.

The nursing shortage also means patients now have to wait longer for care. One exasperated Atlantan took to Twitter recently after his 86-year-old grandmother broke her hip and had to wait three days for surgery “due to lack of staff.”

Last week, Gov. Brian Kemp signed a dozen health care-related bills into law, including one that dispenses tougher punishments for those who harm health care professionals on the job. It also enables hospitals to create police forces. “The Safer Hospitals Act” became law May 2, less than 24 hours before a gunman killed one patient and injured four others in a medical office in midtown Atlanta.

GNA, the state’s largest professional group of registered nurses, called the new law “an important step toward ensuring nurses are able to practice free of the threat of violence.”

The nationwide shortage of nurses is expected to improve by 2035, according to national workforce estimates released in November. In fact, some states are projected to have an excess supply of RNs by then. Georgia, however, is expected to see a 21% shortage of RNs by then, the second-worst among the 10 states projected to have the largest deficit of nurses in 2035, according to the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis’ nurse workforce projections. The state of Washington is projected to have the worst shortage.

Steps are being taken to address Georgia’s nursing shortage and other challenges:

- Financial incentives. Georgia offers student loan repayments of up to $10,000 a year for physician assistants and advanced practice nurses working in underserved rural counties. Last week, Gov. Kemp signed SB 246, creating a loan repayment program for nursing instructors.

- Fast-track nursing partnerships. The University of North Georgia and Northeast Georgia Health System teamed up last year to create an accelerated, 15-month Bachelor of Science in Nursing program for students who already have a bachelor’s or master’s degree in other subjects. The program is expected to add 280 nurses to the workforce over the next five years, beyond the nurses UNG already trains.

- Artificial intelligence in the emergency room. Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing is using HAL model-5301, the world’s first AI-enabled patient simulator to train nurses. It can be connected to ventilators and monitors to simulate real hospital settings.

Despite the grueling challenges brought on by COVID and the nursing shortage, Umeibe and Westmoreland are undaunted.

Umeibe plans to get a master’s in nursing and wants to become a nurse practitioner. “For me, nursing has definitely been unexpected,” he said. “Getting a master’s will give me a little bit more stability.”

As for Westmoreland? “I could retire at any minute but I love what I do,” the 59-year-old said. “I’ve got a lot of years left to work. I’m going to be here for a long time.”

Want to know how many different kinds of nurses are in your county? Find out here.

You can reach Tammy Joyner on Twitter @lvjoyner or at [email protected]. Joyner is State Affairs senior investigative reporter in Georgia. A Georgia transplant, she has lived in the Peach State for nearly 30 years.

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …