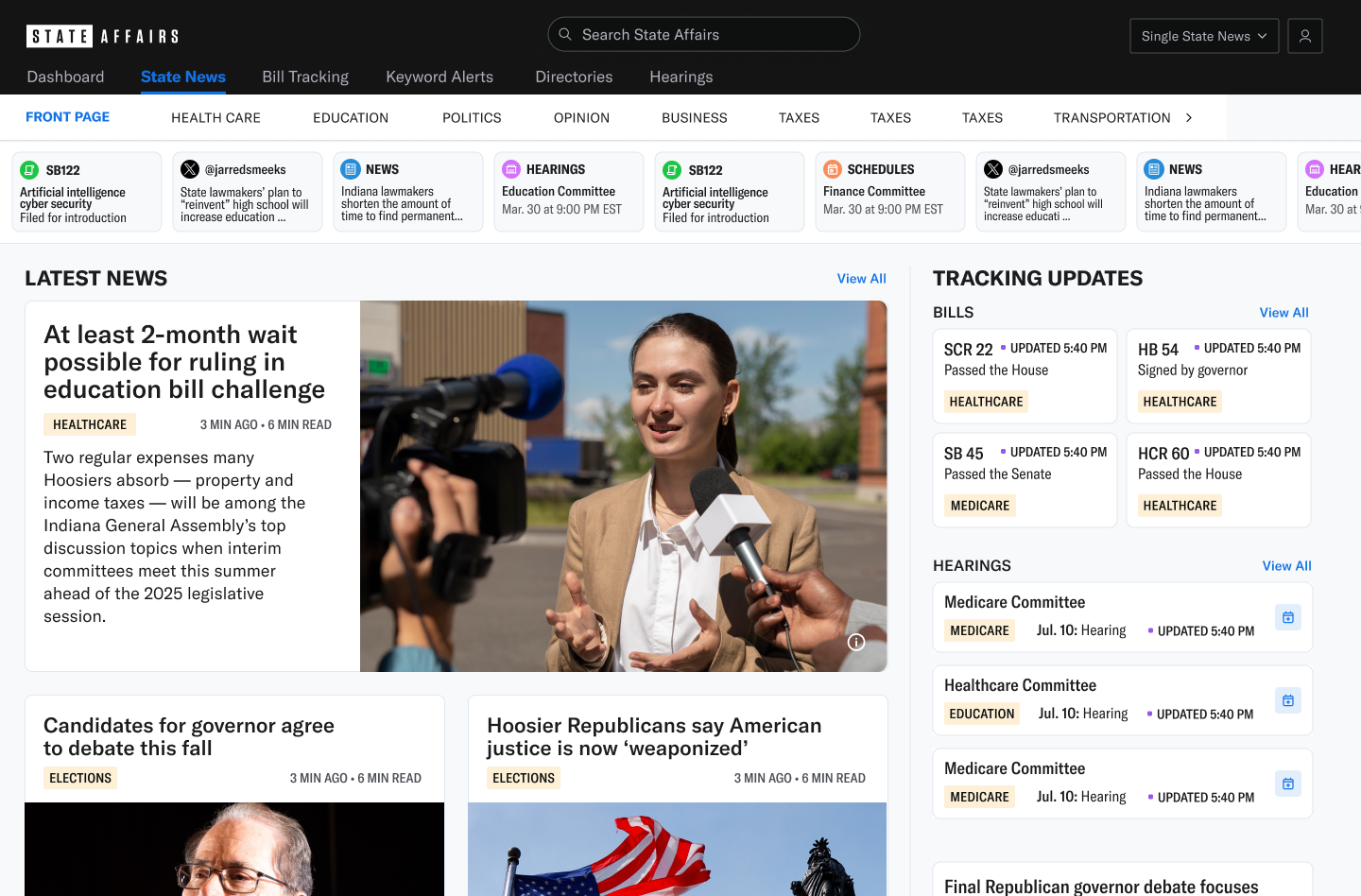

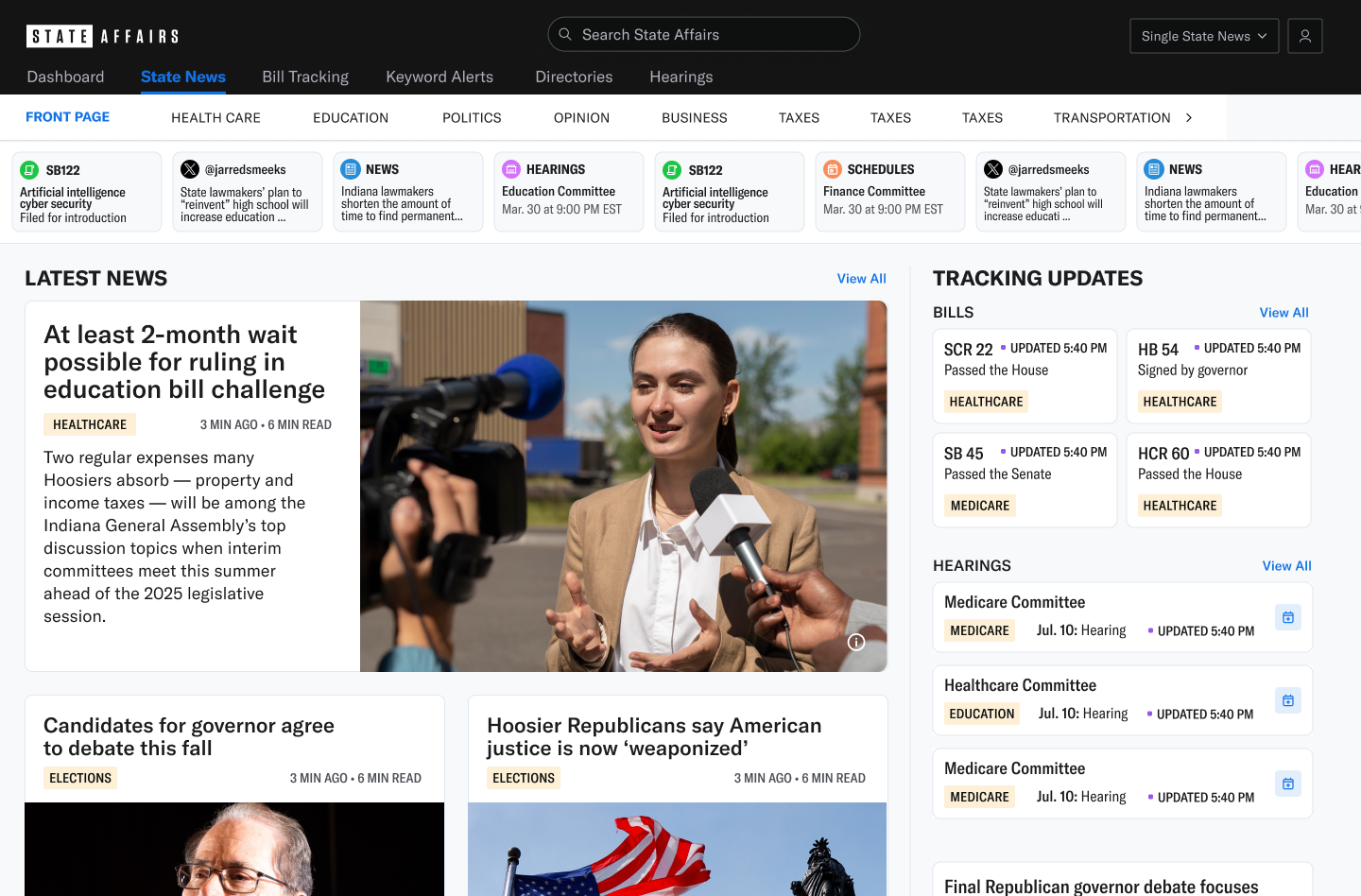

State news and AI-powered policy intelligence—personalized, nonpartisan, on-the-ground, and built for those who act first.

Trusted by thousands of organizations across the United States

%201.png)

%201.png)

Original nonpartisan reporting. Nationwide reach. Unmatched legislative depth.

Our Local, Nonpartisan Statehouse News Brands

See how our AI-tuned tools help individuals, teams, and organizations stay ahead of policy change.