Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo

Chief Justice Holly Kirby listens to arguments in a redistricting appeal in Nashville on Oct. 3, 2024. (Credit: Erik Schelzig)

- A three-judge chancery court panel in November upheld House maps but threw out Senate ones

- The state argues a voter in Nashville had no standing to sue over the the Senate ignoring numbering rules

- The plaintiffs told the justices it's up to the state to prove good faith motivations in drawing House maps

Tennessee Supreme Court justices pressed attorneys on questions about standing and who holds the burden to prove good faith — or the lack thereof — in a challenge of new state House and Senate maps drawn following the 2020 census.

A three-judge chancery court ruled in November that the House maps withstood a constitutional challenge brought by attorneys backed by the Tennessee Democratic Party. But the panel agreed that the Senate had ignored a requirement for multiple districts in a single county to be consecutively numbered. The state filed a challenge to the Senate ruling, while the plaintiffs want the state’s highest court to throw out the House maps as well.

Assistant Solicitor General Philip Hammersley argued plaintiff Francie Hunt, a Nashville resident, didn’t have standing to sue over the Senate decision to have the districts in Nashville to be designated as 17, 19, 20, and 21.

Voters in 1966 approved the constitutional amendment to extend Senate terms from two years to four. As part of the change, about half of the chamber’s seats are up in a presidential election year, and the others coincide with the gubernatorial cycle.

“The problem with Ms. Hunt’s standing is that she perceives a constitutional violation itself to be an injury in fact which is sufficient to confer standing to sue,” Hammersley said. “And that is not the case.”

Justice Sarah Campell inquired who would have standing to sue to enforce the constitutional provision if Hunt did not. Hammersley said he was unwilling to say “anyone definitely does or does not have standing,” but speculated that a county commissioner who had to administer more elections under the new maps might. Chief Justice Holly Kirby said she couldn’t follow that argument.

“The only injury that you can pose to us is a county commission who says that’s too much trouble?” she said. “I mean that’s not why the constitutional provision was enacted, right? It has to do with continuity of representation and the populace.”

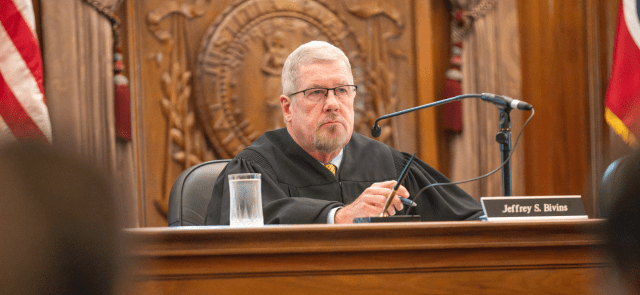

Justice Jeff Bivins noted that Hunt did not miss her turn to vote for her state senator every four years under the new plan. Plaintiffs’ attorney Scott Tift responded that what she had missed was “her right to vote for a staggered-term legislator.”

House maps

The House challenge rests on the claims of plaintiff Gary Wygant that his home county of Gibson was improperly split. The state Constitution bans splitting any counties, but past state Supreme Court decisions aimed at balancing the rule with the federal one person-one vote principle have allowed for up to 30 county splits as an “upper limit” while urging lawmakers to cross “as few county lines as possible.”

Tift argued that because any plan that splits counties inherently violates the constitutional ban, it is up to the state to prove that it did so in good faith. But during the chancery court proceedings, the state successfully moved to block testimony or the release of deliberations, drafts, and other preliminary materials because they were covered under attorney-client privilege. Therefore, Tift said, the state had failed to prove the decisions in their 30 county splits had been justified.

“Our founders decided to ban dividing counties. We don’t know why they did,” Tift said. “It’s been in there for 200 years, and when you divide the county, you are expressly violating that constitutional provision.”

Hammersley argued that past decisions placed the burden on the plaintiffs to show that lawmakers had engaged in bad faith. He also intoned that the time for challengers to present rival maps was during the deliberation over redistricting, not later as past of a lawsuit.

If political motivations behind redistricting are justified, Bivins asked, what would prevent the House from dividing all 95 counties in the state?

“The Legislature could do that, your honor,” Hammersley responded. “I have no reason to believe they would do that.”

But Hammersley said such a move would come with “consequences from the people in the state of Tennessee who could see that and vote out their legislators.”

Know the most important news affecting Tennessee

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

Tennessee voter registration deadline is Monday night

Take note, procrastinators: Monday is Tennessee’s deadline to register to vote in the Nov. 5 general election. The ballot includes races for president, a U.S. Senate seat, all nine congressional seats, all 99 state House seats and 16 of 33 state Senate seats. As of June 1, the state had 4.8 million active voter registrations …

Rogers, Slotkin lean into China, national security in US Senate battle

LANSING, Mich. — Michigan voters are faced with a choice for U.S. Senate in November between two candidates with strong national security credentials but with sharply different views on how to effectively address threats to the U.S. Both Southeast Michigan candidates, Republican Mike Rogers of White Lake and Democratic U.S. Rep. Elissa Slotkin of Holly, have been …

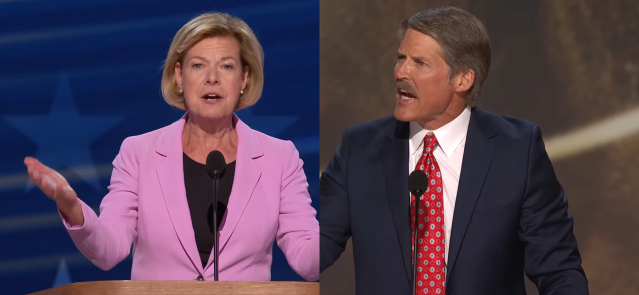

Tammy Baldwin faces tough reelection: Can Trump supporters push her past the finish line?

MADISON, Wis. — Tammy Baldwin may need some Donald Trump supporters to secure her reelection. The two-term U.S. senator plays up the “buy American” language she pushed for federal infrastructure projects and touts policies favored by Wisconsin’s dairy industry such as seeking to ban labeling plant-based products “milk.” Her GOP rival Eric Hovde, meanwhile, wants …

Brown vs. Moreno: Incumbent faces biggest reelection challenge yet

COLUMBUS, Ohio — The 2006 election ushered in a new era of Ohio leadership following 12 years of Republican control. Democrats won back the governor’s mansion and three of the four other executive offices while also narrowing Republican majorities in both chambers of the Legislature. Adding to the blue, near-sweep of top state races was …