Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoDoes Georgia Spend Too Much on School Administrators Instead of Teachers?

Illustration by Brittney Phan (State Affairs)

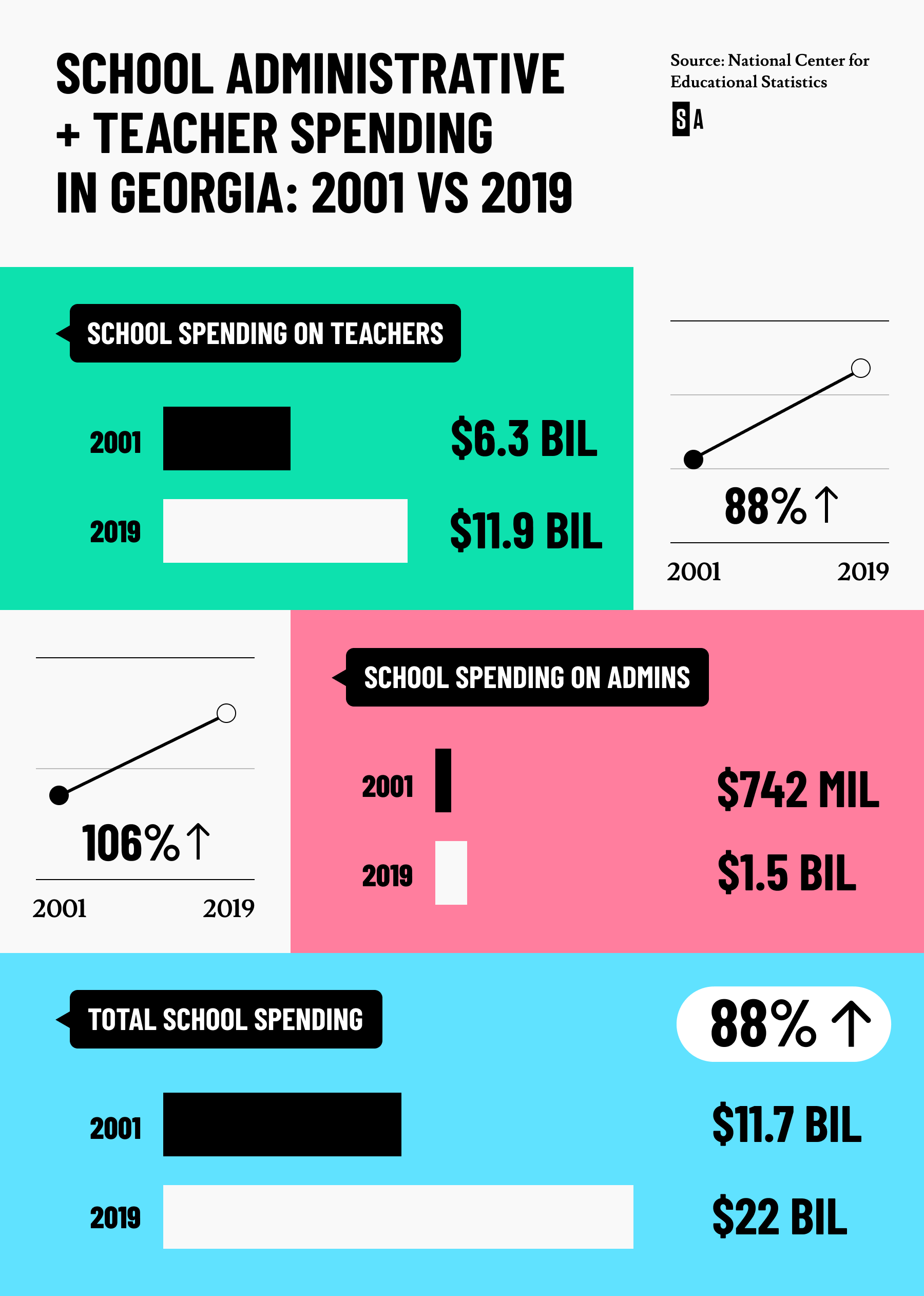

- Georgia increased spending on public k-12 school administrators by 106% from 2001 to 2019 – compared to an 88% spending increase for teachers.

- Georgia’s teacher salaries ranked in the bottom third of states in 2019 amid rising costs to employ principals and superintendents.

- Critics question whether taxpayer money would be better spent on boosting pay for teachers instead of increasing administrative staff.

Costs to pay public-school administrators in Georgia more than doubled over the past two decades, rising faster than the state’s annual spending on teachers and classroom supplies, State Affairs has found.

Across the U.S., states increased their budgets for superintendents, principals and their office staff by an average 89% between 2001 to 2019 – roughly the same rate as public k-12 teachers, federal data shows.

But in Georgia, spending on school administrators swelled by 106% during that time, eclipsing the 88% increase in spending for teachers. That puts the Peach State among the top third of states in spending more on – and staffing up – local administrators.

The spending gap has left some advocates in Georgia wondering if the extra administrative money might have been better put toward teachers – while others stress the importance of quality school leadership amid more testing and accountability requirements from state and federal officials.

“Some of (Georgia’s school) districts, I’m not going to say they have more administrators than they need, but they certainly have a lot of them,” said Jimmy Stokes, a retired Georgia educator and former executive director of the Georgia Association of Educational Leaders (GAEL).

Breaking Down the Costs

While Georgia’s public-school spending has climbed steadily since 2001, the rate of cost increases for local administrators and their staff rose by roughly 20% higher than spending hikes for teacher salaries and benefits, teaching assistants and supplies like textbooks, according to data from the National Center for Educational Statistics.

As costs for administrators shot up more rapidly than for teachers, so too did the overall number of administrative staff working in Georgia schools compared to teachers, federal data shows. Georgia’s teaching ranks grew by 30% from 2001 to 2021, while the number of administrators increased by 41%.

Federal data also shows a gap in salary increases between teachers and administrators, particularly for local principals and their staff. From 2001 to 2019, the amount Georgia spent on teacher salaries rose by 68%, while local principals and other school administrators saw a 92% increase.

The increase in non-teaching staff across Georgia’s school system – particularly among administrators – has made it tough to raise teacher pay high enough to compete with other states and the private sector, said Benjamin Scafidi, an economics professor at Kennesaw State University who studies national trends in school finances.

In a 2017 report, Scafidi estimated Georgia could have spent around $485 million more on teachers between 1992 and 2015 by matching the rate at which non-teaching staff grew with student enrollment growth. That could have translated to an extra $4,352 in teacher pay, Scafidi said.

“We keep adding (non-teaching) staff at a rate much higher than the increase in students,” Scafidi told State Affairs. “All this money on adding staff was money that couldn’t go to teacher salary increases.”

Georgia is one of only six states that do not factor low-income students into their annual school-funding formulas. Read our recent reporting on this issue by clicking the image above. (Credit: Brittney Phan for State Affairs)

Salaries and Support in Schools

Georgia ranked in the bottom one-third of states for average teacher salaries and benefits at roughly $65,000 in 2019, the most recent available year of comparable national data – though teachers did get a $3,000 raise in 2020 with another $2,000 raise expected later this year. Several other states including North Carolina and Florida have also raised teacher pay since 2019.

Several recent studies pegged low pay as a main driver of teacher turnover, including a 2021 report from the Professional Association of Georgia Educators (PAGE) that found nearly 30% of teachers with 20 years of experience or less plan to leave the profession within 10 years, largely due to “salary and school leadership.”

Amid low pay, many local teachers report they plan to switch careers in the coming years after butting heads with supervisors – an issue highlighted in a recent PAGE survey of roughly 4,600 educators, which found 27% of teachers surveyed who have 20 years of experience or less cited problems with school leadership as the reason why they’re considering leaving the profession.

When it comes to school administration, more staff doesn’t automatically mean better teacher morale and student performance, said Verdaillia Turner, president of the Georgia Federation of Teachers. More important is having experienced educators in leadership roles who understand what teachers and students need to succeed – especially amid more accountability measures and state oversight in recent years, she said.

“We support having a strong administrative base,” Turner told State Affairs. “But principal means lead teacher, not lead overseer.”

Georgia Southern University published a 2020 study that noted administrators “play a small but significant role” in boosting teacher productivity and turning around scores for struggling students. It found teachers in a suburban Georgia district reported feeling more engaged with their work when they received strong support from their local administrators.

Local administrators play key roles in a wide range of areas from promoting good classroom environments and evaluating performance metrics to leading teacher development and making sure schools are safe, said John Zauner, the executive director for the Georgia School Superintendents Association and a retired principal and superintendent.

Principals and superintendents need enough staff to manage all those responsibilities – a task that has required more time and work as Georgia has added more accountability and performance measures in recent years to the regimen of standardized tests that students take.

“It’s very easy to cast a stone and talk about school systems being administratively heavy,” Zauner told State Affairs. “All the administrative responsibilities, they’re not decreasing. They’re increasing.”

Scafidi pushed back on that argument, highlighting federal data that shows school administrators across the U.S. were already growing at a faster rate than student enrollment before 2003, when officials passed the No Child Left Behind Act that instituted many of the accountability and testing requirements now in place.

“I don’t know how much we can attribute that increase to testing and accountability,” Scafidi said. “I’m skeptical of that.”

Georgia struggles to stretch its tax dollars when it comes to turning around test scores and graduation rates for thousands of students in low-performing public schools. Read out reporting on this issue by clicking the image above. (Credit: Georgia Governor’s Office of Student Achievement)

Every School is Different

Some studies have also pushed back on researchers like Scafidi’s findings on non-teaching staff costs, noting administrators receive a much smaller share of states’ education budgets overall than teachers.

In the 2021 school year, classroom instruction made up about 65% of the roughly $20 billion Georgia spent on public schools – down 2% from how much classroom instruction received in 1996, state Department of Education data shows. At the same time, the funding share for administrators rose 2%, rounding out to roughly 12% of what it cost to run Georgia schools last year.

Stokes, the former GAEL executive director, pointed out not all school districts in Georgia have boosted their administrative staff more than teachers. Federal data shows some districts saw the reverse happen, such as Camden County along the South Georgia coast, which shrunk its administrative staff by 13% while growing its teacher numbers by 13%.

But many school districts have piled on administrators at a far faster clip than teachers since 2001 – in some cases by a rate twice as large or more. Atlanta Public Schools bumped up their administrative staff numbers by more than 50% compared to a 4% increase among teachers. In rural Clay County, the school district’s teacher numbers dropped by 4%, while administrators swelled by 150%.

Typically, school districts with larger property-tax bases like Atlanta have more revenue to spend on hiring additional administrative staff, Stokes said – giving richer districts in Georgia more room to bring on extra administrators, while poorer districts have to make do with what they can afford.

“It really boils down to what kind of district you have,” Stokes told State Affairs. “It’s a disproportionate system, I’ll put it that way.”

What else do you want to know about Georgia’s k-12 schools and what the state is spending on public education? Share your thoughts/tips by emailing: [email protected].

Newly minted Senate Minority Leader Harold Jones II: ‘I’m not the typical back-slapping politician’

Nearly 10 years into legislative life, Sen. Harold Jones II wouldn’t change anything about the experience. “I love every minute of it. Even when I hate it, I love it,” the 55-year-old Augusta Democrat told State Affairs. Come January, Jones will add another role to his legislative duties: Senate minority leader, a job held for …

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …