Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoLights, Camera, Tax Credits: A Peachy Deal for Hollywood, but What About Georgia Taxpayers?

- Hundreds of movies and TV shows filmed in Georgia since 2005 have drummed up more than $24 billion in economic activity.

- Supporters trace the film industry’s local boom to tax credits worth billions of dollars.

- Critics say film out-of-state companies benefit too much by selling tax credits to the tune of $2.9 billion since 2016.

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

Bill adds violation to Soil Amendment Act, but will it stop the stench?

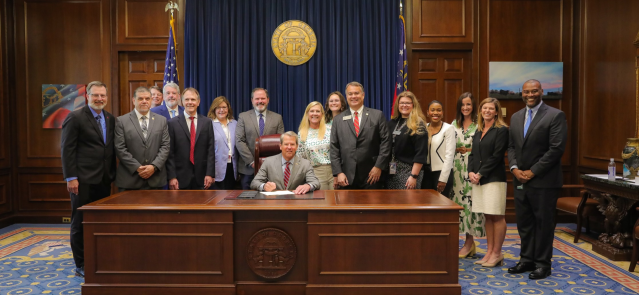

After years of enduring intrusive, foul-smelling waste spread on untold tracts of rural land, Georgians living near such sites are finally getting some relief. On Monday, Gov. Brian Kemp signed into law a bill that adds a new violation to the state’s 48-year-old Soil Amendment Act. Soil amendment is meant to help farmers create healthier …

House speaker Jon Burns hires new communications director

House speaker Jon Burns, R-Newington, announced today that he has hired a new communications director. Kayla Roberson, who has served as press secretary at the Georgia Chamber for the past year or so, will now oversee all external communications, media relations and strategic messaging for Burns. “I’m excited to welcome Kayla to our team,” Burns …

Global bird flu disrupts Georgia exports, costing chicken producers millions

ATLANTA — A global bird flu that has rapidly spread from birds to dairy cows, milk supplies and humans has cost untold millions of dollars in lost export business in Georgia, the nation’s leading poultry producer, officials with the state Department of Agriculture and poultry industry said. Georgia has had only three reported cases of …

Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs and drink milk? Answers to your most pressing questions about the latest bird flu outbreak

A two-year-old strain of bird flu has heightened concerns in Georgia and the rest of the country after the virus recently spread to dairy cows. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and its impact on Georgia and the rest of the country. What are the symptoms of this flu in humans? Eye …