Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoLast week a lucky player in California hit it big, winning the entire $1.7 billion Powerball jackpot that had been accumulating since July.

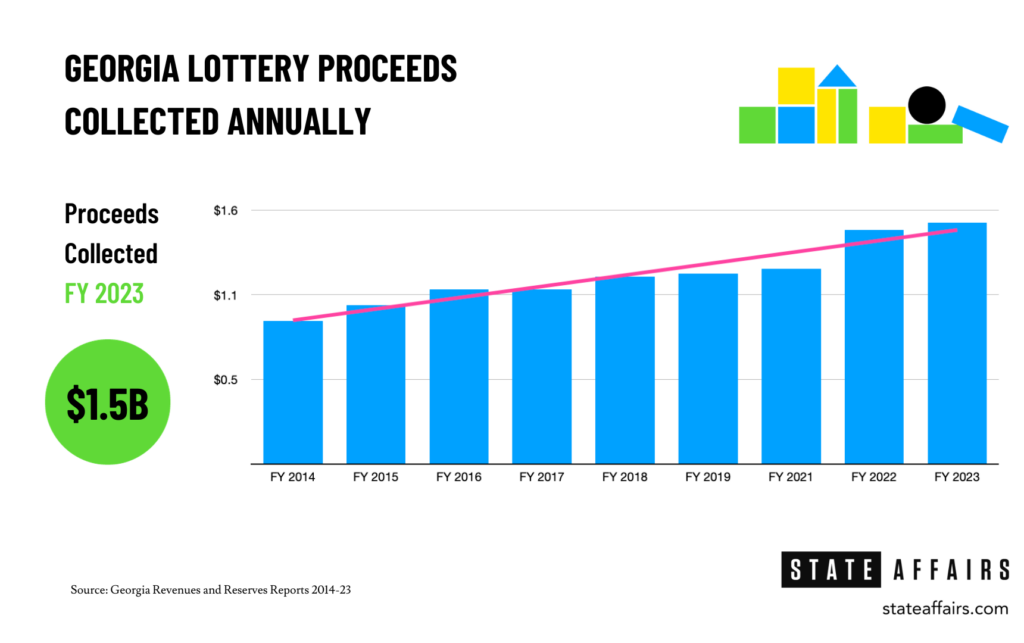

Georgia won, too, collecting $31.5 million for pre-kindergarten programs and HOPE college scholarships during that three-month jackpot run. Those funds were added to the state’s ever-expanding education lottery reserve, which now tops $2.1 billion.

As $1.1 billion in federal pandemic relief funding to stabilize child care centers in Georgia winds down, early childhood education providers are facing the prospect of cutting wages, losing staff and reducing their enrollments. Some are looking at closing their doors.

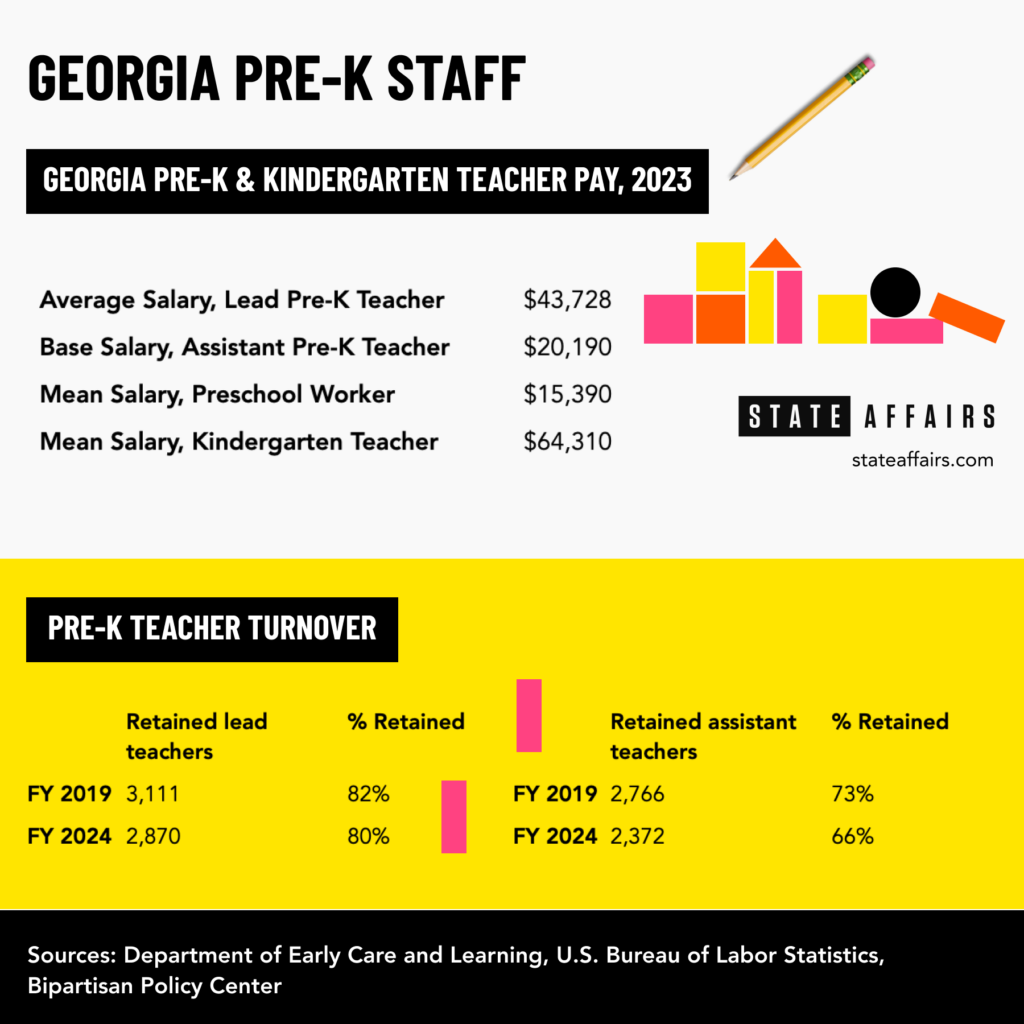

In Georgia, 81% of child care centers are experiencing a staffing shortage, according to the National Association for the Education of Young Children. And the state has lost about 640 pre-K teachers since 2019, reports the Department of Early Care and Learning.

With a turnover rate of 37%, assistant pre-K teachers, who are paid $20,195 by the state, make up the majority of vacancies in both private and public school-based pre-K programs. Because both lead and assistant pre-K teachers are required positions, some programs facing stubborn staffing shortages have had to close their pre-k classrooms.

“Providers are expected to meet the social, emotional and educational needs of each child with too few staff. Turnover is high, and qualified applicants are few … Staff really need to have certifications or degrees to do their jobs effectively, but they’re paid less than fast food workers,” Becky Lehto, association child care director of the YMCA of Coastal Georgia, told members of the House Early Childhood Education working group last week.

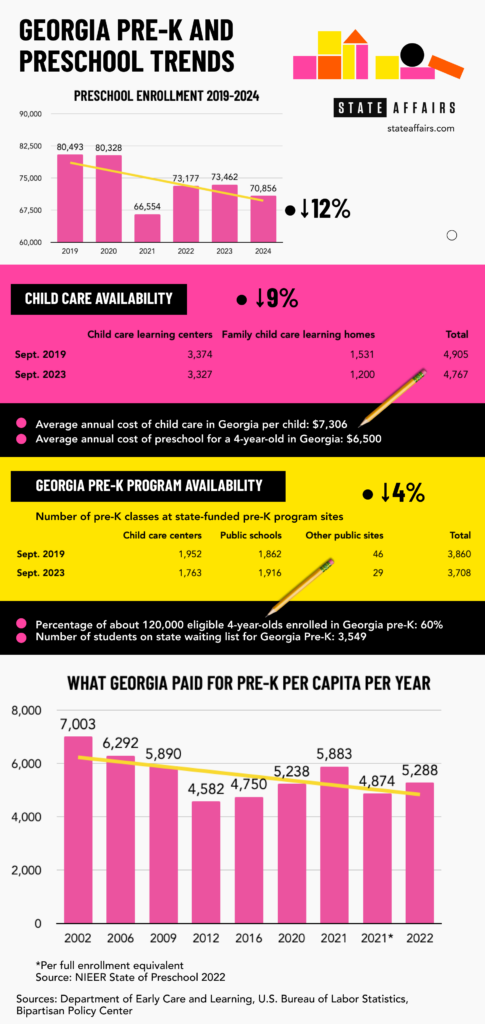

Georgia enrolled 70,856 children in licensed pre-K programs this fall, a 12% drop from the 80,493 children enrolled in 2019, prior to the pandemic. Only 60% of the state’s eligible 4-year-olds are now being served in pre-K programs.

Show me the money

While pre-K centers struggle, advocates are saying: Spend the lottery reserve money. Which is exactly what the Georgia lottery fund is intended to do — pay for pre-K and fund the HOPE scholarship program.

Similar questions have been asked by a bipartisan group of legislators who introduced a bill last session to create a study committee to look at how lottery revenues and reserves are used for educational programs.

Noting that “the state treasury has amassed lottery reserves built up from unspent surplus funds that far exceed the mandated benchmark” (50% of the prior year’s net lottery proceeds), HR 281 calls for “thorough and serious consideration” of using surplus lottery funds to reduce pre-K class sizes, increase teacher pay, and provide capital to expand pre-k classrooms. It also aims to make college more accessible for low-income students.

The bill didn’t get a hearing in the Higher Education committee last session, but co-sponsor Rep. Sam Park, D-Lawrenceville, the minority whip in the House, hopes that it will next year. In any case, he said, “I’ll be working with my colleagues to create a proposal where we are really investing this surplus into children’s education, as it should have been invested over the past few years.”

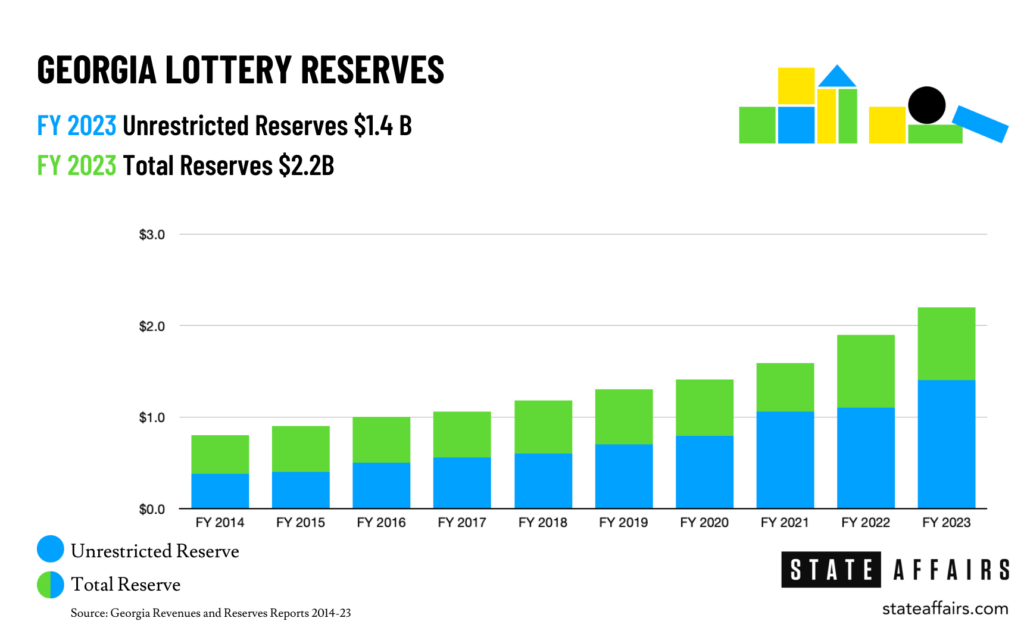

Several Powerball jackpots surpassing $1 billion over the past year have stoked ticket sales and fattened the lottery reserve to record levels, according to a report released by the state accounting office this week.

The reserve for Fiscal Year 2023, which ended in June, was $2.164 billion. That includes $737 million in restricted reserves, which must be held back in case of a shortfall in lottery sales, and $1.4 billion in unrestricted reserves, which can be spent at the discretion of legislators and the governor. Historically, they’ve chosen not to do so.

Those reserves are what’s left after doling out $1.4 billion in lottery proceeds for pre-K and HOPE scholarship programs in FY 2023. For FY 2024, the Legislature has budgeted $444 million for pre-K and $956 million for higher education.

Child care providers and advocates are asking lawmakers to use the lottery surplus and other state funds to raise pre-K teacher salaries, increase funds for pre-K classroom operations, and lower class sizes from 22 to 20 students.

Ife Finch Floyd, director of economic justice for the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, told legislators that the $2,000 pay bump given to pre-K teachers this year, while welcome, will be eroded by inflation and rising living costs.

Floyd advocates raising the starting pay of assistant pre-K teachers to at least $30,000, and for their salaries to grow “through some combination of experience and credentials. This would mean the lead teacher pay scale would adjust upward, too.”

The average salary of lead pre-K teachers in Georgia is $43,728, according to the Department of Early Care and Learning. That’s significantly lower than the average salary of $64,310 for a public school kindergarten teacher. The Budget and Policy Institute has proposed achieving parity between pre-K and kindergarten teachers by increasing pre-K per student funding from $5,285 to equal the per capita rate of $7,032 for kindergarten students. That would cost about $147 million per year.

“The reserves may not be sufficient enough for sustaining the pre-K program for the long term,” said Floyd. “ … But I think it’s an important opportunity to at least put a down payment on boosting those salaries in a meaningful way, and … to make sure that our pre-K teachers are remaining in the classrooms.”

A national crisis

What’s happening in Georgia is part of a national child care crisis. Since 2020, the early childhood education industry in the U.S. has lost 88,000 jobs, or 8.4% of its pre-pandemic workforce, according to the Center for American Progress.

“You can’t look at pre-K without looking at the rest of the early care system, and it really is collapsing in what economists call a market failure,” said Donna Davidson, CEO of Easter Seals of North Georgia, which started the school year with 90 teacher vacancies among its 44 preschool sites. She’s had to cut child enrollment at two of her centers due to the staff shortage and the impending loss of federal aid, resulting in 283 children losing their spots.

“This is one service that is really dependent on what parents can pay,” she said. “ … We have to have a solution that has a large public investment in early childhood education.”

Loni Smith, director of the Sheltering Arms Barack and Michelle Obama Center, a preschool in south Atlanta, is all for receiving more lottery money to make her programs whole. The center is operating at 80% capacity this year, due to a shortage of 12 pre-K teachers. Across its 13 early care centers, Sheltering Arms is down 100 teachers, and is operating at 70% capacity.

Smith said she’s found it hard to compete with Target, Publix, Amazon and Walmart, which offer higher salaries, better benefits and even help their employees with college. “And they don’t have the level of stress, the assessments, the parent complaints that come with teaching in a classroom,” she said.

To hold onto the teachers she has, Smith said she’s planning to keep the hourly rate for those with associate degrees at $15 an hour and bachelor’s degrees at $18 an hour, wages that were raised over the past three years with federal American Rescue Plan Act relief funds. The $935,000 her center received from ARPA this year, now representing about a third of her budget, will be gone by November. So she’s planning to raise tuition across the board.

Her clients with 3-year-olds will now pay $240 instead of $220 a week, an $80 a month increase.

“That will be a problem for some of our families,” said Smith, particularly for those parents who are gig workers who drive for Uber and DoorDash, and others who are part-time educators. They earn too much to qualify for the state’s Child Care and Parents Services subsidy, which covers child care tuition for students from very low income households and those who have special needs. “But we have to sustain the program,” Smith said.

‘What’s the point of keeping all that money?’

The pending tuition increase was worrisome news to Jazline Brown, 32, a single mother whose two young children attend the Obama preschool, which she says offers great teachers, a high-quality curriculum, and “a place where I know my child is safe, and just has a wonderful atmosphere and spirit.”

A special education teacher for Atlanta Public Schools, Brown currently gets a tuition scholarship from Sheltering Arms for her 2-year-old daughter, Cordell, saving $320 a month. The pre-K program for her 4-year-old son Oakley is free, as it is for all students in Georgia.

She said an $80 monthly tuition increase for Cordell next year may mean cutting back on some things, such as the YMCA family membership she’d planned to enroll both children in swimming and ballet lessons.

“It’s going to be paycheck-to-paycheck again,” said Brown. “I wish there were more programs that kind of help us middle-class working families, to make child care more affordable.”

Learning of the latest lottery surplus, she said, “They really need to be pumping all those funds back into education. I should be getting a tuition break. Day care is essential so we can work. … And they need to give all the day care workers and pre-k teachers raises. What’s the point of keeping all that money if it’s meant for education?”

Rep. Park said he anticipates the challenge in getting the state to tap deeply into the reserves “will be your ideological back and forth on the size and role of government, and should the government be making such a large investment, and is this going to be sustainable for the long term? You know, ‘Is this going to grow government?’

“ … For me, government should just be effective,” said Park. “If the size is big or small, that’s just an adjective, really, if government is supposed to be vying for the people, especially when it comes to a need such as this, where it would create broad societal benefits, from workforce and economic development, to, you know, breaking the school-to-prison pipeline and building safer communities in the long term.”

He added that he hopes Republicans “will be willing and open to getting a better understanding of some of these proposals, and certainly to moving some of those proposals along, not just from the legislative perspective, but also from the appropriations perspective.”

Republican Rep. Todd Jones, R-South Forsyth, a member of the Early Childhood Education working group who also serves on the Appropriations education subcommittee, told State Affairs that he and others in the group are open to using more lottery funds for pre-K and other education needs.

“I think everything is on the table, in terms of not just looking at the lottery funds, but also looking at how we are currently investing money in terms of the positive impact for our children, starting at birth all the way through,” he said. “ … If we don’t solve the birth to 4 problem, frankly, we’re never going to solve the K to 12 challenge.”

House Speaker Pro Tem Jan Jones, R-Milton, who chairs the working group and also serves on the Appropriations committee, signaled during last week’s meeting that she’s aware of the stakes for early childhood education providers if they don’t get more state support.

“We know there’s a cliff now with inflation and the expiration of the federal funds that have helped through this difficult period of the last three years, and we share your concerns,” she said.

Later in the hearing, Jones observed that the $8,000 the state offers centers for pre-K program start-up costs — which actually average closer to $25,000 — “would nowhere near pay for the materials, tables, wash stations” and other items that new centers need. Regarding staffing, she said, “We have a shortage and part of that is because we don’t pay enough, particularly for the assistant teacher.”

Jones said the Early Childhood Education working group will present its legislative and budgetary recommendations for pre-K programs before the next legislative session in January.

Check out our TikTok:

Related stories:

Have questions, comments or tips on the Georgia Lottery or education? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header photo: Lead teacher Juanita Willis interacts with pre-K students at the Barack and Michelle Obama Center in south Atlanta. (Credit: Jill Jordan Sieder).

Newly minted Senate Minority Leader Harold Jones II: ‘I’m not the typical back-slapping politician’

Nearly 10 years into legislative life, Sen. Harold Jones II wouldn’t change anything about the experience. “I love every minute of it. Even when I hate it, I love it,” the 55-year-old Augusta Democrat told State Affairs. Come January, Jones will add another role to his legislative duties: Senate minority leader, a job held for …

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …