Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo

Many state employees in Georgia work at the James H. "Sloppy" Floyd Building in Atlanta. (Credit: Beau Evans for State Affairs)

- Program for thousands of struggling students caves in three years.

- Tension built between program leader and state schools chief.

- Audit targets consultant fees and spotty oversight.

Ordered by Woods’ office, the audit identified about a dozen outside contracts at the turnaround office that rounded out to two years’ worth of about $1.3 million, nearly a third of the office’s total spending through mid-2019.

Auditors questioned why some consultants secured contracts that roughly doubled their daily pay rates from $500 a day to $900 or $1,100 while invoices they submitted appeared to give vague descriptions of what work was done. The audit also probed whether Thomas improperly influenced the state’s contracting process to pick certain consultants, resulting in a method that the Georgia inspector general’s office later concluded was faulty.

“Overall, it appears that the Chief Turnaround Office was mismanaged and that policies and procedures in place were routinely ignored by (Thomas),” the inspector general’s office said in a letter from January 2020.

Thomas strongly objected to the audit’s findings in two lengthy formal responses, calling it “a biased and unfair account” that aimed to do away with his program entirely. Notably, the auditors did not seek interviews with himself or many of the program’s key staff, Thomas said. He provided documentation showing the contractors in question put in bids that sought thousands of dollars less in daily pay than those submitted in competing bids. He also pointed out that contractors’ work was tracked in regular progress reports and performance reviews from local school officials.

As for contractors’ pay, Thomas said some outside consultants were tapped to kickstart the program’s work in the middle of the 2017-18 school year before the program had time to flesh out its finance staff. Those consultants later formally rebid on contracts once their initial terms were up, leading to higher compensation amounts, he said. Thomas also denied influencing the contractor-selection process, chalking the accusation up to allegations from some disgruntled staff. He noted the audit found no evidence beyond hearsay that he or anyone else had improperly influenced picking contractors.

Overall, Thomas argued the audit served only as ammunition to dissolve the turnaround program and justify his removal. He sought to block the audit’s public release in court, claiming it could damage his prospects for finding future employment after he resigned.

“The audit appears to have been a retaliation to my efforts to promote collaboration and a smear campaign to harm me and the Chief Turnaround Office,” Thomas said.

Contracts were not the only source of tension. Some turnaround staff claimed they weren’t reimbursed for travel expenses while other staff and consultants were, including one specialist who argued in a lawsuit that she was wrongly denied travel pay to work in Macon-Bibb County schools. Thomas countered that he followed rules set by the state’s travel policy for all agencies when making decisions on travel pay, noting the education department did not have its own internal policy on the subject.

Other lawsuits have come from Daryl Fineran, a former specialist in the turnaround program who filed a whistleblower complaint about the contracting practices. He claimed consultants took home larger pay for less work than regular staff, triggering a lopsided workload that worsened the program’s political head-butting with the state agency.

“Bottom line, it was all done in good faith hoping to help failing schools,” Fineran said in a recent interview. “They just hired the wrong person to run it.”

Rather than replacing Thomas, state school officials chose to phase out the turnaround program entirely. Some of its staff were hired by the state school-improvement division, which was already working with nearly 190 other struggling schools throughout the program’s tenure. Then, lawmakers axed the turnaround program’s budget in June of 2020, about six months after Woods assured the General Assembly that his agency could absorb the program’s loose ends without any hiccups.

“I don’t foresee we will miss anything at all with that,” Woods told state lawmakers during budget hearings in mid-2020. “In fact, I think we will probably be stronger.”

Amid the controversy, Thomas maintained that schools under his turnaround program outperformed many other struggling schools in the state, particularly in some rural areas where students have long stumbled with test scores and general academic improvement. He also stressed the program’s importance, noting that many of Georgia’s elementary and middle schools continue to rank in the bottom half among schools nationwide in reading, math and science scores even as the turnaround program got underway.

“We have assisted schools and districts in creating the conditions for ongoing success,” Thomas said in a statement accompanying his resignation. “Ultimately, the State of Georgia needs to decide how to improve the outcomes that it is presently getting in education.”

NEXT

Part V: School improvement moves on

Header image: James H. “Sloppy” Floyd Building in Atlanta. (Credit: Beau Evans for State Affairs)

Election administrators ‘in limbo’ over new voting rules, top official says

If you plan to hand-deliver your absentee ballot to your local election office this year, you’ll have to show identification and sign a form stating whose ballot you’re dropping off, under a new rule recently passed by the State Election Board. If you fail to show your ID or don’t complete the form, your ballot …

Weekend Read: State Election Board marks its 60th year mired in controversy. Here’s what happened.

In 1964, Georgia lawmakers retooled the state’s election process to create a “one person, one vote” system after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the “county unit system” that held sway over Peach State politics for nearly half a century. Until then, politicians hoping to win primaries in Georgia had to capture entire counties, not just …

State lawmakers: Atlanta, give detention center to Fulton to fix problem-plagued jail

Atlanta city officials need to give the Atlanta Detention Center to Fulton County to ease overcrowding in the county’s violence-prone jail, a bipartisan panel of state lawmakers said in its final report, released Friday. “A big part of the solution is that the City of Atlanta needs to turn over the Atlanta Detention Center to …

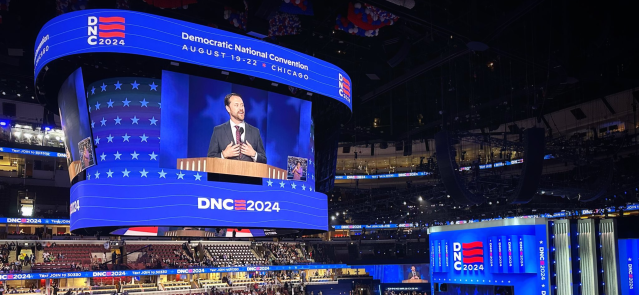

Georgia plays a prominent, although louder, role at this convention, too

As the second of the two biggest political party events wraps up this evening in Chicago with Vice President Kamala Harris accepting the Democratic presidential nomination, all eyes in Georgia are turning to the grand finale — the Nov. 5 election. “We are all energized because we know we are bringing back hope for our …