Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoLegislators schedule special assembly to address redistricting, but will they make headway?

(Design: Brittney Phan)

ATLANTA — For the second time in two years, Georgia lawmakers will make a late-autumn pilgrimage to the Capitol to participate in America’s most political of political activities: redrawing electoral maps.

A federal judge has given state legislators until Dec. 8 to reformulate district lines on congressional, state Senate and state House maps to make sure they better reflect the growing share of Black residents among Georgia’s voting-age population.

The remapping done during the eight-day special session, which begins Nov. 29, could affect the outcome of some races in the 2024 election, as well as who runs for office next year.

For veteran political observers, political junkies and neophytes interested in seeing their government at work, it’s a chance to watch the latest round of how Georgia reapportions — or not — its political power.

While legislative mapmakers will be shape-shifting political lines to meet U.S. District Judge Steve Jones’ mandate, it’s also a time of political jockeying. It’s likely to pit Republicans against Democrats. Democrats against Democrats. Republicans against Republicans. It could create major upsets in the 2024 election. Political careers may be on the line — or possibly come to an end — with the reconfiguration of a district line.

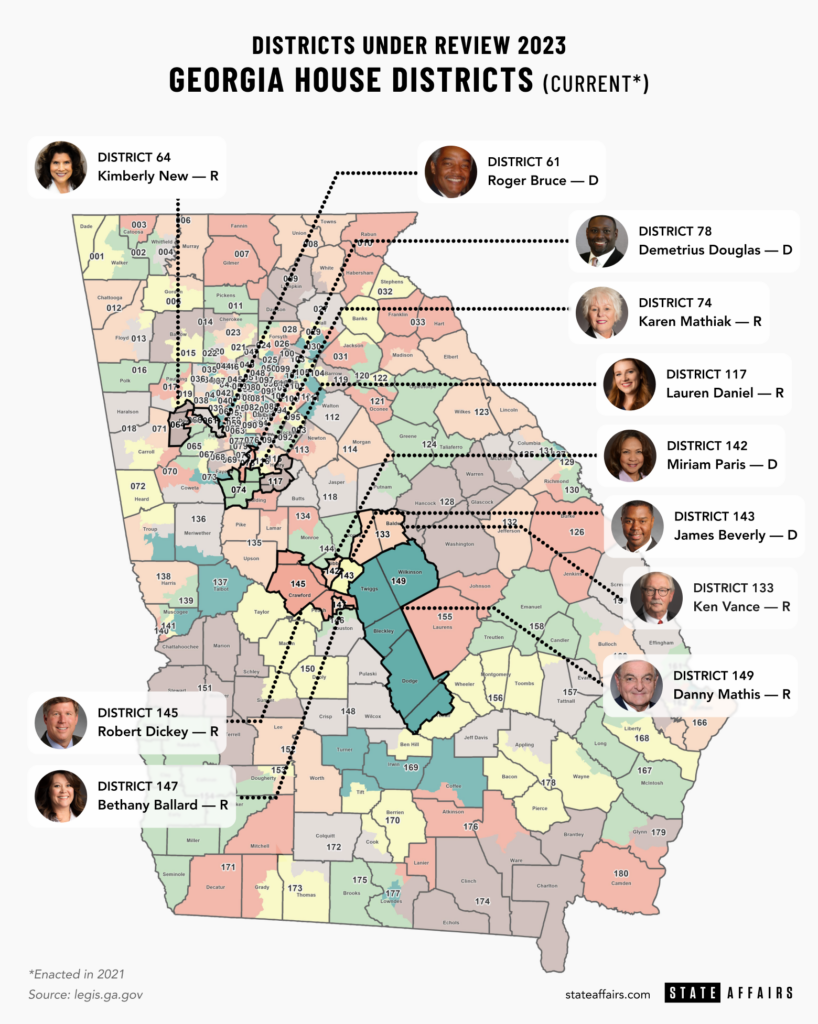

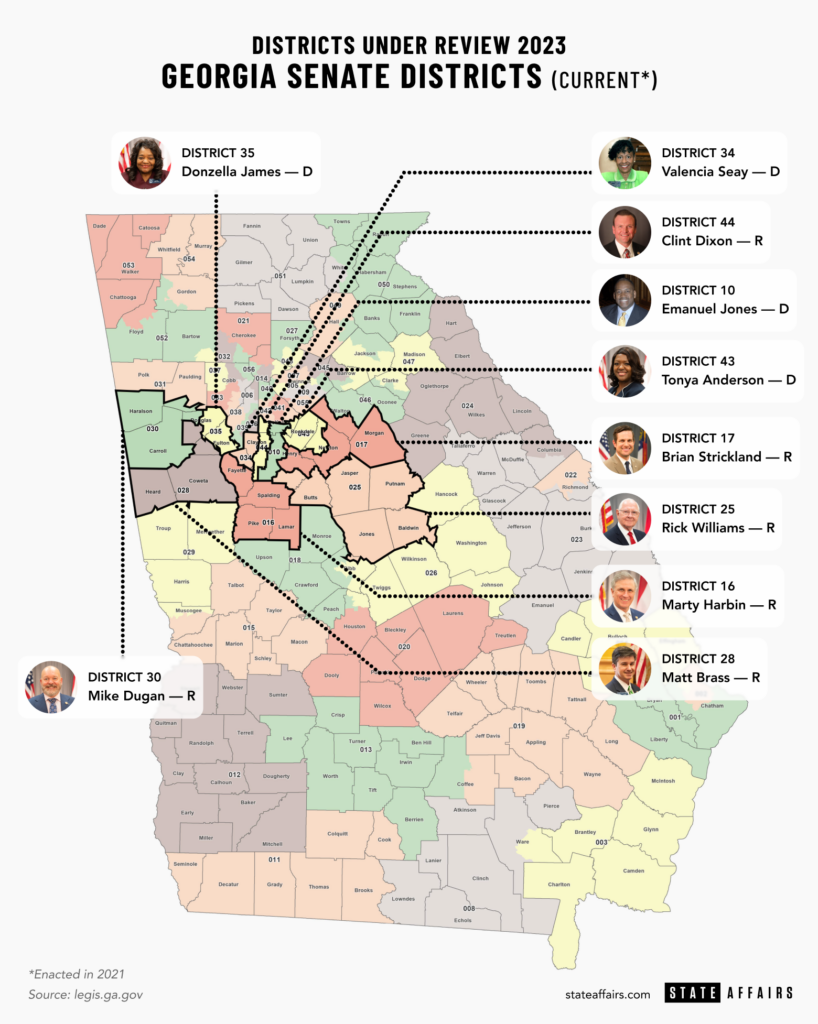

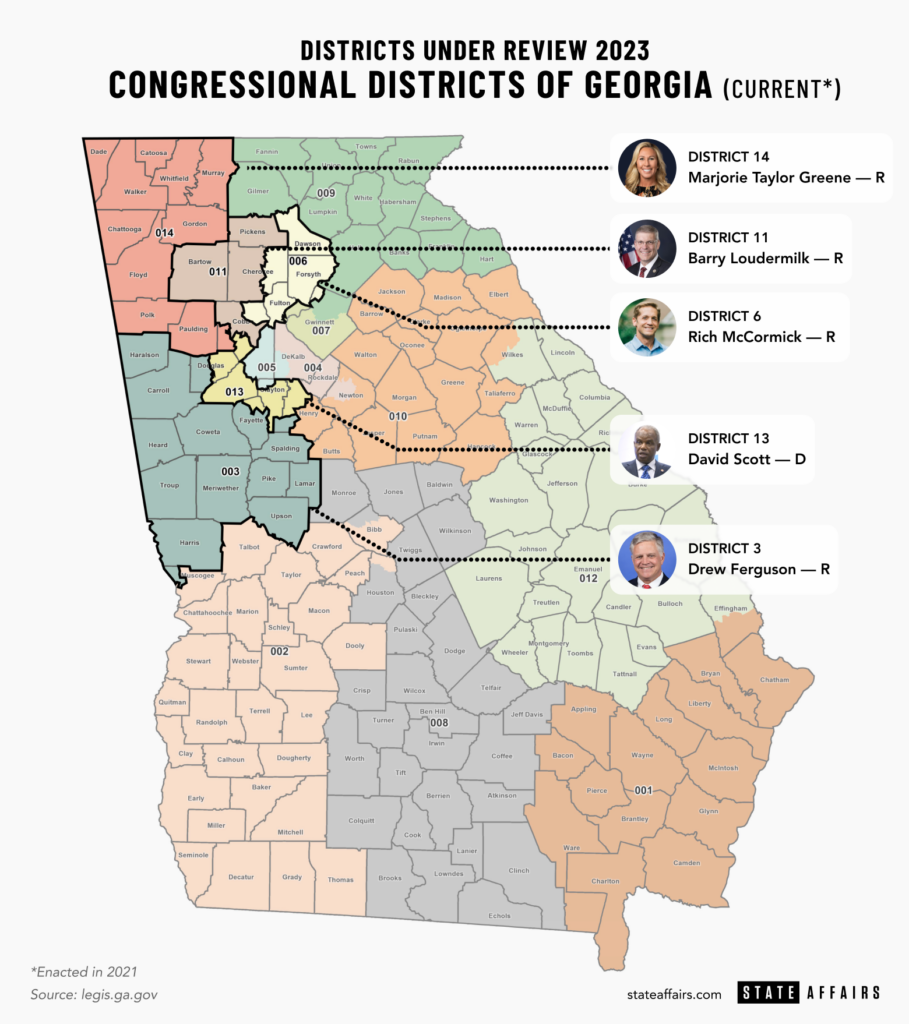

The issue that has led to the special legislative session springs from Jones’ finding that Georgia’s legislative and congressional maps dilute the power of Black voters, violating the Voting Rights Act, which bars electoral practices that discriminate on the basis of race. In his Oct. 26 ruling, Jones ordered Georgia to draw new maps before the 2024 election that include additional majority-Black districts in metro Atlanta and around Macon.

“It’s not the most swashbuckling activity but it’ll be an interesting thing to watch,” Princeton University professor of neuroscience Sam Wang told State Affairs. “If they make narrowly tailored changes, then that’s likely to be in compliance. If they make larger-scale changes then there are the questions of why.”

Wang is director of the Princeton, N.J.-based Electoral Innovation Lab whose projects include the nationally-renowned Princeton Gerrymandering project. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project project uses a scientific and mathematical approach to check the political and racial fairness of redistricting.

“Will the Legislature take a responsible approach and comply with a court order without, you know, playing games, or will they try to do something more complicated?” Wang said.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project gave Georgia an overall grade of “F” based on racial fairness for its 2021 congressional map. The state Senate map also got an “F” while the state House map got a “B.”

Doing their homework

Georgia lawmakers are likely already creating maps to present at the session, experts say. Unlike 2021, when they had to overhaul their entire maps to adjust for population changes, this redistricting session could — and should – be a rather straight-forward session, University of Georgia political science professor Charles Bullock III said.

“If they go in with their ducks in a row, which I assume they probably will, they could do this fairly quickly. It’s a much less demanding task than they had back in 2021,” Bullock, the nation’s preeminent authority on redistricting, told State Affairs. In addition to tracking the process in Georgia since the mid-1960s, Bullock has written a book about redistricting.

Judge Jones gave specific instructions on 26 congressional, state House and state Senate districts to focus on. But it all boils down to how the Republican-led Georgia General Assembly approaches the process.

Georgia’s congressional delegation currently has nine Republicans and five Democrats. The state Senate has a 33-23 Republican majority and Republicans outnumber Democrats 102-78 in the state House.

“If your objective was to comply with a court order, it would be easy to draw that well in advance of the session and just present it and say, ‘Fellas, you may not like this, but this is the way it is and adopt it and let’s go do our Christmas shopping’,” said Emmet J. Bondurant, a nationally-known Atlanta trial attorney, now retired, who has argued voting rights cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. “If you don’t do any preparation, and you come in there with everybody coming in with their own ideas, it’s going to be a mess. I hope they will not do that.”

‘We don’t want to be Alabama’

Getting it wrong again won’t bode well.

Just ask Alabama legislators who defied court orders to fix their racially-discriminatory congressional map. In October, a federal court picked the state’s new 2024 congressional map drawn by a court-appointed special master, after giving the state two chances to fix its maps.

The court’s plan created a near-majority-Black district in Alabama, along with a majority-Black district so that Alabama now has two districts (the 2nd and 7th congressional districts) where Black voters will have the opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.

“We don’t want to be Alabama. Georgia has to be careful to eliminate the drama and theater, so we don’t end up possibly being like Alabama,” Tharon Johnson, a Democratic strategist and chief executive of Paramount Consulting Group, told State Affairs.

Johnson called Jones’ ruling “a historic decision and very pivotal, not just for partisan purposes but just to really make sure the growth of our state and the demographics are being recognized legally.”

Brian Robinson, a Republican strategist and Johnson’s Political Breakfast podcast counterpart, said he believes “Republicans have every intent of fulfilling [Judge Jones’] wishes and taking a different route than Alabama did.”

Bringing in a third-party to fix the maps, Robinson said, is a “Code Red that Georgia Republicans can’t afford, and won’t allow it to happen. The Alabama legislators wouldn’t make the tough political choices, so even worse choices were made for them.”

Robinson noted that “two [Alabama] Republican congressmen were put in a district together and now have to run in a primary against each other. That’s awful. No one wants to see that.”

Filling the pasta bowl

With the specter of Alabama’s fate hanging overhead, Georgia legislators will likely proceed accordingly.

“There are, like, billions of ways to draw maps,” Wang said. “They’re all slightly different from one another. But the key would be to observe broad principles of racial fairness and compliance with the law. It’s kind of like saying ‘how many ways can I fill a bowl of pasta?’ There’s a million ways to do it. In the end, what you need is a bowl of pasta.

“It’d be as if you could just move the Atlanta city limits once in a while just because you felt like it. It’s just the most incredible activity,” Wang added. “Redistricting is mind blowing. I mean it’s nerdy, but it’s mind-blowing.”

Bullock said this redistricting session could lead to some seats being flipped in the 2024 election.

“This doesn’t change the Legislature. It just peels off a few more seats for Republicans,” Bullock said. “It won’t wipe out the Republican majority but it will make them a bit narrower.”

State House Minority Leader James Beverly, D-Macon, has high hopes that the redistricting process could help to tilt the balance of power in the House, which currently has 102 Republicans versus 78 Democrats, in a direction that gives Democrats more influence.

“With the new maps redrawn, we could move to 83, 84, 85 seats. Now we’re at a jump ball in how the House is going to be governed. The whole conversation will change. … And if people vote Democratic in their districts, I guarantee it will change everything,” Beverly said. “So we’ve got to mobilize the voters, through town hall meetings and all the things you need to do to engage the public to let them know what’s at stake … Things like expanding Medicaid will be back on the table.”

Robinson, the Republican strategist, added “I think there are numerous visions for how this is going to play out. We’ll see how much of a role Gov. Kemp plays in it.”

Bullock noted that seats actually gained or lost in elections don’t always pan out as the majority party who redrew the maps had envisioned.

“Lawmakers are drawing political lines that have to see them through the next decade even as the state continues to grow and diversify in population,” Bullock said. “What you’re having to do is look around the corner and over the hill. You don’t know what’s going to happen. If you’ve been underestimating what happened over the next six, eight years, you may find yourself with a very different political world than you did when you had drawn the districts.”

Bullock cited the 2018 election where Democrats gained 15 state House seats in metro Atlanta. Those were districts drawn by Republicans in 2011 after the 2010 census, he noted.

“Undoubtedly they thought they were drawing districts that would last for 10 years but a lot of them didn’t,” Bullock said.

Democrats have also faced partisan gerrymandering backlash. In 2001, the Democratic majority in the General Assembly created new maps that “packed Republican districts and unpacked Democratic districts,” said Ken Lawler, chair of the nonprofit Fair Districts Georgia. “It was a terrible gerrymander, one of the worst.”

The 2001 maps led to a 2004 court case that overturned the enacted state House and Senate maps, followed by one of the only elections in Georgia over the past two decades that relied on a court-drawn set of maps, which Lawler said ended in “a pretty fair result, when you look at vote share in statewide elections in 2004 versus seat share.”

He noted that both parties have been “extremely guilty”of partisan self-dealing in drawing electoral maps over many decades, taking advantage of their majority power and state law that requires only that districts be contiguous. Redistricting guidelines direct lawmakers to make districts compact, to avoid pairing incumbents, and to respect “communities of interest.” But they also include an “escape clause,” which says the reapportionment and redistricting committees can “take into account any other factors they deem appropriate,” said Lawler, “which means the committees are pretty much free to do what they want.”

No Straight Flush

In the round of redistricting to come, Robinson believes Republicans will obey the letter of the law and fulfill the judge’s wishes but not necessarily the Democrats’ wishes.

“The Democrats are hoping that they pick up some seats out of this. And maybe they will,” Robinson said. “ But it’s not going to be the straight flush that some think it is. They actually may lose other members because the Voting Rights Act isn’t about party, it’s about race.”

For instance, Robinson said you can change a district that’s got a heavily Black population but a white Democratic member, and make that a majority-Black district. You might get a new Black member at the cost of a white Democrat, he said.

Creating racially-fair electoral maps has become a big challenge, in and out of court.

Georgia’s recent case is among a half dozen lawsuits across the South where courts have found maps in violation of the Voting Rights Act, Wang said.

Nationally, over 70 cases have been filed, challenging congressional and legislative maps in 27 states as racially discriminatory or giving dominance to one political party, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a progressive, nonprofit law and public policy institute at New York University School of Law. Roughly 45 of those cases are pending in trial or appellate courts.

As of July, legislative and/or congressional maps have been redrawn in Alaska, Maryland, New York, Ohio and South Carolina due to legal challenges, the center noted.

Georgia’s appeal has become the state’s Achilles’ heel, electorally speaking. People have flocked to the state for its sunny climate and good-paying jobs and now the Peach State must account for that growth in political representation.

Redistricting occurs after each U.S. Census, which is held every 10 years. It is done to make sure the population changes are reflected in the various electoral districts.

Between 2010 and 2020, Georgia gained more than a million new residents, making it one of the nation’s top five states in population growth.

Blacks and other people of color accounted for the bulk of that growth. Statewide, the number of Black Georgians grew by 13% or roughly 484,000 people. Asian and Hispanic populations increased by 53% and 32%, respectively. The white population dipped by 1%.

Additionally, between 2000 and 2019, Georgia’s eligible voter population grew by 1.9 million, according to Pew Research Center, with nearly half of that increase being attributed to growth in the state’s Black voting population. Having more Blacks and other people of color should have created more political representation on Georgia’s electoral map, especially among Blacks. But it didn’t.

“We told the Legislature in 2021 that they did not have enough Black majority districts in those maps. They didn’t listen,” said Lawler, of Fair Districts Georgia, which partnered with the Princeton Gerrymandering Project to create what it considered fair maps. Those maps were then submitted to lawmakers. “And they went about their business, and here we are.”

The Remedy

Which brings us to U.S. District Judge Steve Jones’ Oct. 26 ruling.

His order identifies five congressional districts as well as 10 state Senate and 11 state House districts as out of compliance with the Voting Rights Act. Jones has ordered the state to draw additional majority-Black districts in metro Atlanta and near Macon, as follows:

“The remedy involves an additional majority-Black congressional district in west-metro Atlanta; two additional majority-Black Senate districts in south-metro Atlanta; two additional majority-Black House districts in south-metro Atlanta, one additional majority Black House district in west-metro Atlanta, and two additional majority-Black House districts in and around Macon-Bibb,” Jones wrote.

Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, one of the plaintiffs in the case, commended Jones’ decision.

“Thanks to the court’s decision, these efforts to further disenfranchise Black voters and diminish political representation for the Black community and communities of color, for now, has been halted in the state of Georgia,” the Black fraternity said in a statement on its website the day after the ruling.

Some political observers and redistricting experts called Judge Jones’s 516-page ruling fair, thorough and a good roadmap for Georgia lawmakers.

Robinson says Georgia has come a long way since the 1965 Voting Rights Act was instituted to address Jim Crow-era voting practices that kept Blacks from voting. He cited the fact that Georgians sent Sen. Raphael Warnock, a Black man, twice to Congress and elected U.S. Rep. Lucy McBath from a predominately white district.

“I have no doubt that his [Jones] opinion is well thought out and a reflection of the law,” Robinson said. “ I just disagree in the big picture that Georgia has underrepresented Black opportunities. Our General Assembly’s representation roughly reflects our population. Our Congressional delegation roughly reflects our population.

One big caveat to keep in mind is that Georgia officials plan to appeal Jones’ ruling mandating the redrawing of districts. They’ve decided not to seek a stay of the ruling while the case is under appeal, meaning any new maps approved for the 2024 election cycle could be changed at a later ruling.

“A lot of this law and what it subscribes to is based on the idea that white people won’t vote for Black people, and therefore we have to go to these extraordinary measures to make sure that Black people have an opportunity to vote for a candidate of choice. Georgia has proven that’s not the case. … Really good Black candidates can win and they do win and they beat white candidates, sometimes in majority white districts,” said Robinson.

The power dynamic

Bondurant, the Atlanta attorney,who argued his first voting-related case in 1963, sees it differently. He says Georgia and other southern states still can benefit from federal oversight of the political and voting process.

“What’s behind all of the political wrangling and manipulations and taking incremental steps to do what courts have ordered? Power,” Bondurant said. “At one time, it was white power. Now it’s Republican power, which is essentially the same thing as white power in the Georgia General Assembly, and in some other states. But it’s political power. And it’s democracy be damned. Fairness be damned. We want to be in power. And the Legislature will come up with all kinds of fatuous reasons, supposedly to justify something they know can’t be justified.”

Fair Districts Georgia and 35 other election integrity, civil rights and public interest groups are asking lawmakers to adopt new guidelines to make this year’s redistricting process more transparent, fair, and less partisan than they believe it was in 2021.

In a letter issued on Oct. 30, the groups asked the state’s legislative and reapportionment committee leadership to allow for public input on proposed new maps by making them available for public review before and during the eight scheduled days of committee hearings, and also to invite communities of interest and other concerned citizens to comment at the hearings.

Above all, said Lawler, the scope of changes to the currently enacted maps should not go beyond what the court has ordered.

“Legislators should implement the remedy to the maps to add the majority Black districts as ordered, and not make any other changes not relevant to that,” Lawler said. “We don’t want to see changes that are made for partisan purposes. Here they could be tempted to do more, because you’re kind of opening the patient up for surgery. Our stance is that should not happen. They should implement the remedy, change as little as possible, and that’s it.”

Senior Investigative Reporter Jill Jordan Sieder contributed to this report.

Interested in watching the proceedings? You can do so here or you can see it in person at the Capitol. The Senate gallery on the fourth floor of the Capitol will be open to the public.

Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected]. And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram@StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …