Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoWhy is Georgia facing one of the worst nurse shortages in the country?

Illustration by Brittney Phan

- Georgia has one of the worst nursing shortages in the country and it’s projected to worsen by 2030.

- The nurse shortage has been more sharply felt because of the COVID-19 pandemic but the problem has been mounting for years.

- The pandemic has also fueled a historic increase of travel nurses.

- Experts and nurse advocates say the state can improve incentives for nurses to remain in-state long-term

Georgia has been facing a shortage of nurses for years, but it’s a problem that has recently grabbed headlines because of the COVID-19 pandemic that brought harrowing tales of overworked healthcare workers struggling to keep up with record amounts of death.

The state’s low vaccination rate, still below 50% of the eligible population, only adds to the struggles of medical staff bearing the brunt of a summer spike in cases that pushed Georgia’s death toll past 26,000 and is only now abating. By the end of August, the situation was so dire that Gov. Brian Kemp deployed 105 Georgia National Guard personnel to assist nurse staff at 10 hospitals across the state and urged residents to get vaccinated.

“We’re just tired and burned out. And we need the public’s help: get vaccinated,” said Richard Lamphier, president of the Georgia Nurses Association.

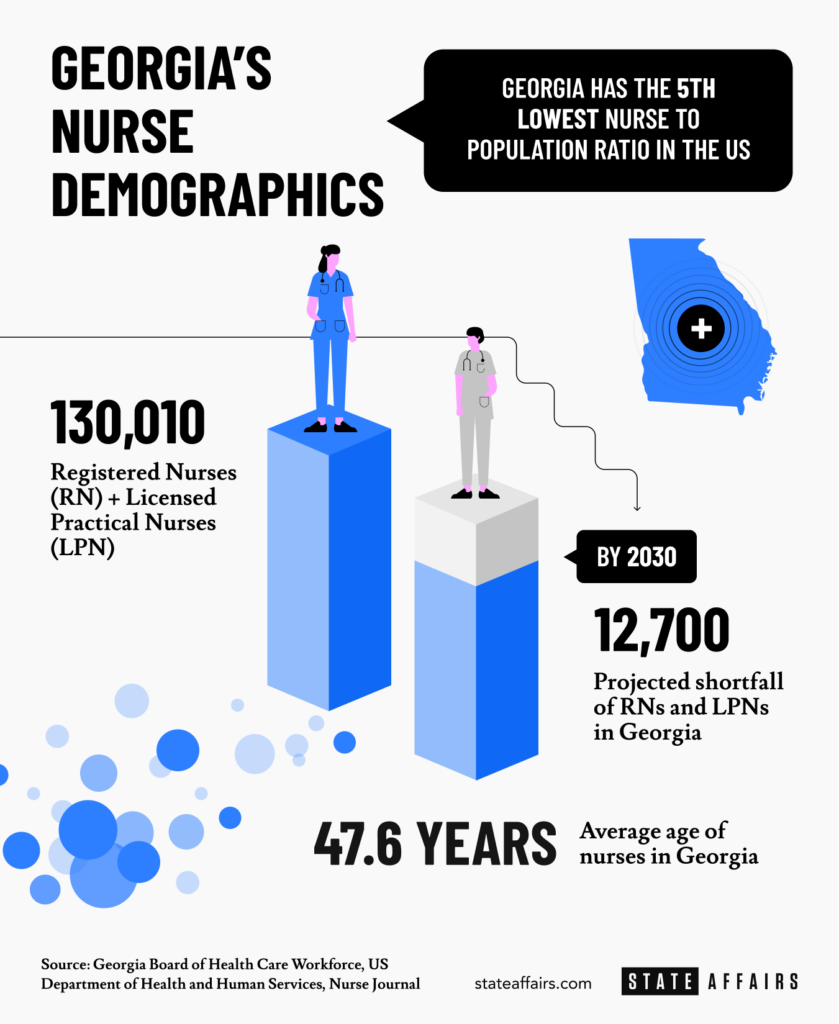

A lack of nurses means patients end up waiting longer for care and exhausted nurses are prone to mistakes, Lamphier said, both of which mean worse outcomes for those hospitalized. Georgia has the fifth-worst nurse-to-population ratio among the 50 states and the state’s per-capita COVID-19 mortality rate is currently seventh-worst in the U.S.

As the state recovers from the latest coronavirus surge, Kemp has already told Georgians to expect another this winter.

Meanwhile, Georgia’s U.S. Senators, Democrats Jon Ossoff and Rev. Raphael Warnock, have made moves to unlock over $160 million in federal funds for Georgia hospitals and community health centers through the American Rescue Plan and COVID-19 relief mechanisms.

This week Ossoff said he would push for the budget reconciliation bill to expand the National Health Service Corps and Nurse Corps to relieve the nurse shortage in Georgia and nationwide.

“COVID-19 has left hospitals and clinics understaffed and medical teams overworked,” Ossoff said.

But there’s more to the nurse shortage than the COVID-19 pandemic. As the state’s population grows and older nurses retire, there aren’t enough new nurses being trained. What’s more, many newly minted nurses take higher-paying jobs out of state.

‘The entire state is affected’

“The entire state is affected, but the specialty areas are really the ones that are being affected the most: in the ICU [Intensive Care Units], the operating rooms, the emergency rooms,” said Lamphier.

There are currently 130,010 registered nurses and licensed practical nurses in Georgia, according to state data. According to labor statistics aggregated by Nurse Journal, Georgia’s nurse-to-population ratio is the fifth-lowest in the nation.

A 2017 study by the US Department of Health and Human Services showed that by 2030 Georgia will require 12,700 more registered nurses and licensed practical nurses than it is projected to have.

A Georgia Senate report in 2007 stated that Georgia had a “severe” nursing shortage and accurately forecasted it would only worsen as the state’s population increased and the nursing workforce ages out. According to the state Board of Health Care Workforce, the average age of nurses in the state is 47.6 years.

A national marketplace

The pandemic, which has driven swings in demand as COVID-19 hotspots wax and wane in different parts of the country, has only strained the supply chain further and driven a historic rise in the number of traveling nurses across the country.

Many hospitals furloughed nurses when elective procedures were halted at the start of the pandemic, but those nurses ended up picking up travel assignments to work in COVID-19 hotspots, Lamphier said.

“Some of them stayed traveling because of the financial benefit that they found while traveling,” said Lamphier.

Travel nurses are managed by private agencies and deployed to a hospital system or state public health agency that contracts them, often with accommodation provided. Contracts might be as short as three months and working hours may be long, but they have the freedom to take as much time off between postings as they want.

Though a small fraction of the overall nurse workforce, travel nurse jobs have risen dramatically. There are an estimated 50,000 travel nurses in the U.S. presently, and 30,000 travel nurse jobs currently listed, according to a Bloomberg analysis.

One nurse State Affairs spoke with called it quits after a decade working in Georgia in favor of travel contracts that she estimated increased her income by $50,000 for the year.

“A nurse can go to New York and work for three or four days in a week, and make twice or three times as much money as what I make in Georgia, and then come back home to Georgia [for the weekend],” said Lamphier. “There’s a flight leaving [Atlanta’s] Hartsfield-Jackson Airport every hour.”

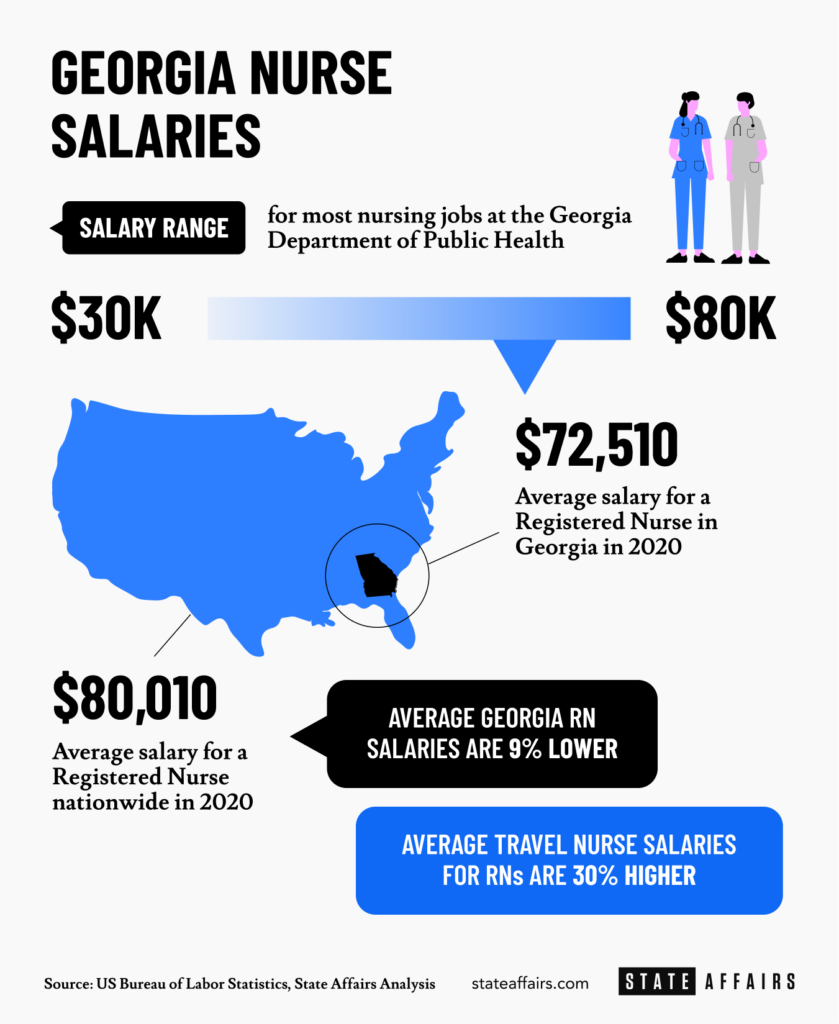

The average salary for a registered nurse in Georgia was $75,510 in 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, with most nurses earning anywhere between $51,270 and $98,810 per year. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows that average registered nurse salaries are 9% higher nationally at $80,010 per year.

A State Affairs analysis of Georgia Department of Public Health salary figures and the nearly 100 department job listings indicates nursing jobs pay between just $30,000 and $80,000 per year.

Travel nurse salaries are estimated to be as much as 30% higher than registered nurse salaries on average, according to Nurse Journal.

Meanwhile, some Georgia hospital systems are reportedly offering signing bonuses of up to $30,000 to compete with demand. The Georgia Nurses Association’s online job board presently shows 1,300 active job listings.

“There’s only so many people in the pipeline, graduating. We need to beef that up, (but) I think nursing salaries are attractive for someone coming out of school,” said Monty Veazey, a former Georgia state representative and current president of the Georgia Alliance of Community Hospitals (GACH), a group representing non-profit hospitals in the state.

“It’s a tough job,” he said. “But we pay pretty good.”

A lack of nurse educators

There’s also a shortage of nurse educators in Georgia, Lamphier said. It’s a problem also identified in the 2007 state senate report on the nursing shortage, which made an urgent call:

“Our state must respond to the impending shortages … the primary focus of any state action should be within the medical and nursing education systems, specifically by expanding medical education enrollment and physician residency training, and increasing nursing faculty salaries and doctoral programs.”

But faculty salary data from Georgia’s public universities shows that on the whole, those salaries have hardly budged.

“Educators are leaving their jobs to go back into the hospitals [as nurses] because they’re making more money,” Lamphier said.

There are state incentives such as a tax credit of up to $8,500 for doctors and $6,375 for nurses and physician assistants that provide uncompensated training to medical students at certain Georgia universities. However, Lamphier notes, this doesn’t address the lack of nursing faculty needed to train nurses at a basic level.

State incentives

According to Stacy Zhang, an assistant professor of Health Policy and Management at the University of Georgia, tuition reimbursement and loan forgiveness is another way the state can retain nurses.

“This is something we can improve upon: scholarships or offering incentives to go into nursing,” said Veazey, the GACH president.

Currently, Georgia offers student loan repayments of up to $10,000 per year for physician assistants and advanced practice nurses working in underserved rural counties with a population below 50,000.

There are also federal student loan repayment programs for nurses that commit to several years of service or teaching in different settings. That said, other states have more generous programs than Georgia such as Wisconsin, which offers nurses $25,000 per year to repay student loans. North Carolina offers up to $60,000 to nurse practitioners and physician assistants in loan repayments for a four-year commitment to work in rural and underserved communities.

A restrictive state for nurses?

Nurse advocates like Lamphier have asked lawmakers to allow nurses in Georgia to practice independently from physicians. Presently, a nurse cannot set up an independent practice, like a clinic, in Georgia, something allowed in dozens of other states.

“My nephew is graduating from nursing school in December, and I can’t convince him to work in Georgia [because of the regulations],” Lamphier said.

“We have been a pretty restrictive state in how nurses practice,” said Veazey. “I think that should be changed.”

For Veazey, “there has to be a happy balance,” but he does not see Georgia nurses operating outside of protocol agreements with physicians.

“That’s something that won’t happen here,” Veazey said, noting that regulations in the state don’t allow nurses full prescriptive authority. “Doctors do not support that, and they have a strong lobbying group.”

According to Zhang, the health policy expert, the evidence suggests that nurses can be given more independence and medical authority in most scenarios without detriment to patients.

“At least with the quality of care provided by nurses, it is as effective as services provided by primary care doctors, and the cost is lower.”

What do you think Georgia should do to address the nurse shortage? Share your thoughts and questions: [email protected].

Newly minted Senate Minority Leader Harold Jones II: ‘I’m not the typical back-slapping politician’

Nearly 10 years into legislative life, Sen. Harold Jones II wouldn’t change anything about the experience. “I love every minute of it. Even when I hate it, I love it,” the 55-year-old Augusta Democrat told State Affairs. Come January, Jones will add another role to his legislative duties: Senate minority leader, a job held for …

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …