Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoHow politics doomed a struggling-schools program in Georgia

Credit: iStock

- Program for thousands of struggling students caves in three years.

- Tension built between program leader and state schools chief.

- Audit targets consultant fees and spotty oversight.

For Eric Thomas, the beginning of the end for a short-lived state program he led to help struggling schools in Georgia came in the form of a meeting that never happened in September 2019.

Tensions had simmered in the two years since the start of the program called the Chief Turnaround Office, set up to help chip away at improving poor grades and classroom experiences for more than 150,000 Georgia students. The would-be September meeting marked a chance for Thomas and Georgia’s state school superintendent, Richard Woods, to patch up simmering ill will. But the two went back and forth in emails over who else should attend, ultimately scuttling the meeting altogether.

That month, state education officials quietly launched an audit to probe the program’s contracting and travel-pay practices. Several rural schools under Thomas’ watch soon missed out on federal money that went to other schools instead. Two large districts had already pulled out of the program. By December, Thomas resorted to secret meetings with a sympathetic colleague for inside information on what the future held for his program, according to documents reviewed by State Affairs in an open-records request. A month later, he resigned, and the program folded.

“It is well-known that the Superintendent’s Office has a hostile relationship with the Chief Turnaround Office,” Thomas said in a statement with his resignation letter in January 2020. He stepped down about five months later. “Over the past six months it became clear that the (two offices) … were not going to coexist.”

In its brief lifespan, the Chief Turnaround Office tapped a team of in-house education specialists and outside contractors to work on shaping up some of the lowest 5% of Georgia public schools. They fanned out to 21 struggling schools from Savannah to the Alabama state line, encompassing nearly 10,000 students.

Many in Georgia’s education sphere trace the program’s demise to its roots in the state legislature in 2017 when lawmakers crafted the program as a largely standalone office answerable to the state Board of Education but not to Woods’ department. Others pin more blame on Thomas himself, viewing his career as a school official in Cincinnati and Virginia as a hindrance to building good relationships with Georgia’s local and state education establishment. At nearly $240,000, his salary was substantially larger than others at the state education agency and almost double that of superintendent Woods. Thomas also weathered strife from some staff within his program who bristled under his leadership, eventually prompting a handful of lawsuits and a whistleblower complaint that sparked the damaging internal audit.

School officials, education advocates and some of the office’s former staff all agree the goal to boost performance for thousands of students in struggling schools across Georgia remains critically important, regardless of whether lawmakers create a special program for it.

“It can be a helpful process if you embrace it,” said Marlyn Tillman, co-founder and executive director of the educational advocacy group Gwinnett SToPP.

But when it came to the turnaround office, she added that “what supposedly (lawmakers) were doing, I don’t give them any credibility because it was set up from a political perspective.”

Turnaround in Terrell County

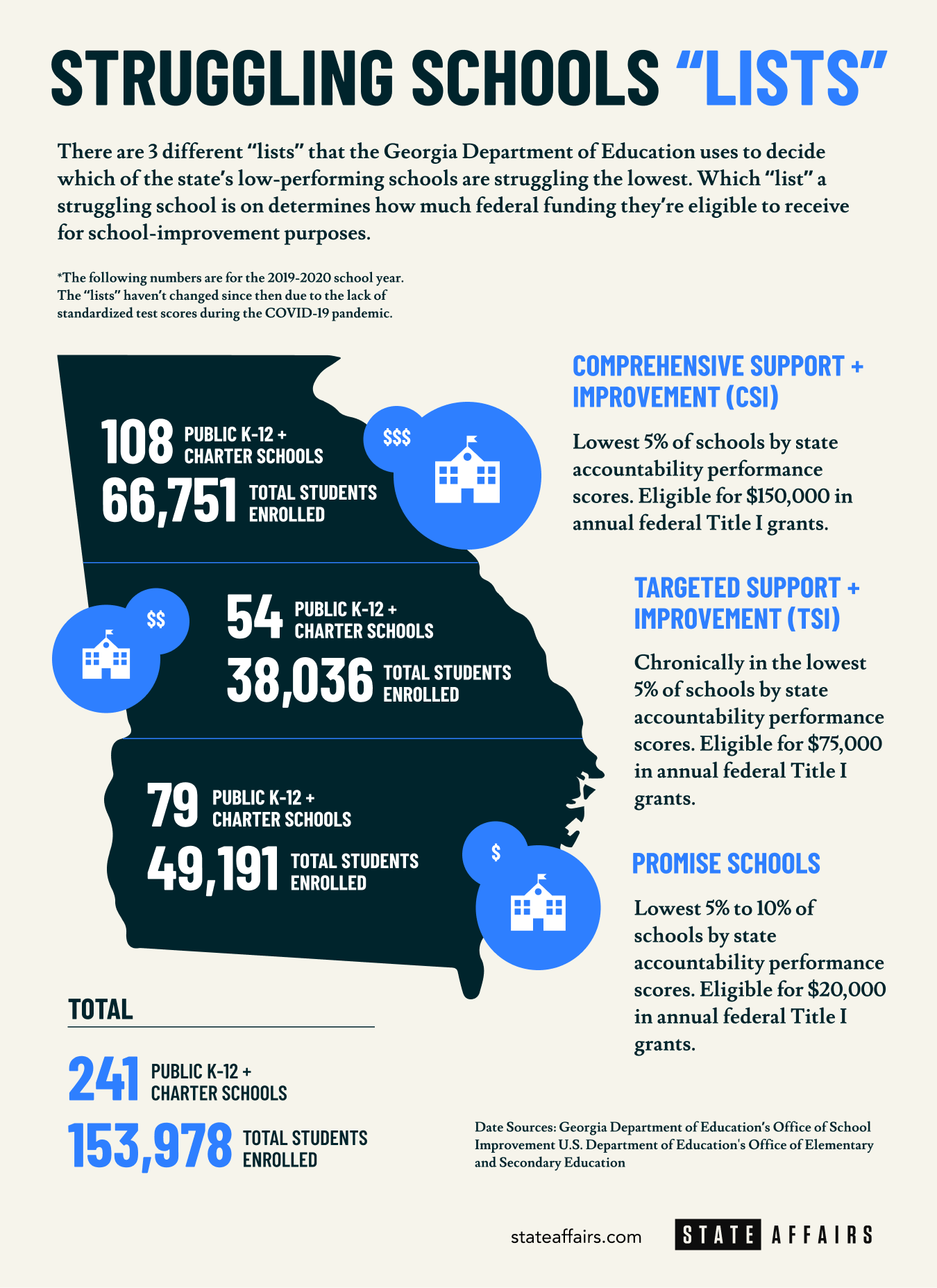

Under federal rules, each year, state officials in Georgia and across the U.S. must identify schools that rank among the lowest 5% in terms of standardized test scores, graduation rates and overall school-climate factors such as discipline issues and student-wellness programs.

Georgia, like other states, has established measures and metrics to identify those schools, which historically tend to represent mostly low-income, minority and rural communities where educational hurdles stem from overarching social and economic challenges.

In Georgia, 162 schools in mostly urban areas like metro Atlanta, Macon and Savannah, as well as several rural areas, fell under the lowest 5% category for the 2019-20 school year — before the COVID-19 pandemic scrambled test scores and student performance. Another 79 schools teetered close to that 5% edge. Nearly two dozen of those schools came under the umbrella of the Chief Turnaround Office, qualifying those local teachers and administrators to work one-on-one with program specialists to analyze performance data, create improvement plans and complete leadership training.

By several accounts, the turnaround program saw gains in some districts like the Terrell County School System, where Cooper-Carver Elementary School in rural Dawson had languished in the test-score danger zone since 2015.

Like similar schools, Cooper-Carver struggled with realizing grade-level academic achievement across multiple subjects, especially in reading comprehension and math, and particularly among minority and economically disadvantaged students and students with disabilities. By 2019, the Chief Turnaround Office’s specialist assigned to Cooper-Carver helped school officials dig into performance data, improve lesson plans, train teachers and overhaul certain weak staff, according to reports provided by the school.

With that assistance, Cooper-Carver’s year-end collective Georgia Milestone test scores climbed from 47 to 69 points between the 2018-19 and 2019-20 school years, said the school’s principal, LaTosha Peters. The specialist also helped arrange mental health services and vision, dental and asthmas screenings, she said.

“They did a great job,” Peters said in a recent interview. “We got off the (struggling schools) list in a year and a half when it was expected to have taken years.”

Overall, more than half of the 21 schools under the turnaround program, including Cooper-Carver, saw federally required performance scores improve between the fall of 2018 and the spring of 2019, according to state data. Several schools saw no issue with the non-Georgia career of Thomas, who was born and raised in Savannah. Local administrators gave high marks on their partnerships with the program and its specialists during the 2018-19 school year, according to surveys reviewed by State Affairs.

“We had so many programs, interventions, curriculum pieces and the like (before the turnaround program), but none of it caused a rise in student achievement,” Tangela Madge, the superintendent of Randolph County School System, said in a 2019 letter to state lawmakers.

“Through effective and succinct 90-day planning, (Thomas) and his team of transformation specialists have helped our middle school experience double-digit gains.”

Debbie Alexander, a veteran educator from Augusta who led the turnaround program’s specialist teams in 2018, also thought the program got off to a good start. But she, like Peters, soon began hearing rumbles from other districts who felt less satisfied with the turnaround work.

“For me, it was really a wonderful experience,” said Alexander, who is now the executive director of the Central Savannah River Area Regional Educational Service Agency. “But (the turnaround program) was short-lived, in my opinion. It had just really begun.”

Politics at play

Amid Cooper-Carver’s success, Peters said she heard complaints from some school leaders about their districts’ assigned specialists. Alexander, who focused mainly on Randolph County schools, heard officials at the Richmond County School Systems were talking about dropping the office entirely.

Before long, the two largest school districts under the program – Richmond County and Savannah-Chatham County – stopped working with specialists. Representatives from those districts declined or could not be reached for interview requests to discuss why.

Discontent from some districts was also relayed to Cecily Harsch-Kinnane, the policy and outreach coordinator for the advocacy group Public Education Matters Georgia. Like many local school advocates, she traced the turnaround office’s downfall partly to how it was set up.

“What it had going was promising,” said Harsch-Kinnane, who formerly served on the Atlanta Board of Education. “But it was always a turf war of sorts.”

The turnaround program emerged after a failed push in 2015 by lawmakers backed by then-Gov. Nathan Deal created a different program called the Opportunity School District, which could assume control of failing public schools in Georgia. School leaders, teachers, parents and voters across the state squashed that program almost as soon as it reared its head, bashing it as an unwanted power grab by the state to take over local schools. Mistrust lingered in the education community when the Chief Turnaround Office was pitched as a compromise idea in 2017.

“This was a difficult issue to take on back then,” said former Rep. Kevin Tanner, who sponsored a bill to create the turnaround office. “The educational community was very skeptical.”

Keeping the turnaround office separate from Woods’ larger agency was done partly to avoid another clash over state takeover, said Tanner, who is now the county manager for Forsyth County. The approach won support from the legislature’s majority Republican members and powerful Democratic leaders such as 2018 gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. But seven local school advocates interviewed for this story all agreed the split between Thomas’ turnaround program and Woods’ state agency created friction from the start, particularly since the state already had a division under Woods that worked with struggling schools.

“It was creating a duplicative department,” said Lisa Morgan, president of the Georgia Association of Educators. “Politics reigned supreme rather than thinking what’s best for our students and educators.”

Support for the turnaround program waned after Gov. Brian Kemp took office in 2019, shortly before Woods lobbied lawmakers to bring the quasi-independent program under his direct watch. Kemp showed less interest in continuing the program than did his predecessor Deal, according to advocates. He also appointed several new state education board members who were not involved in the program’s creation.

Thomas, the turnaround chief, noticed collaboration with Woods tapering off after the program’s first six months, giving the impression that he and his staff were being iced out despite a mandate from the state legislature that the two offices work together, records show. Woods’ office also still controlled the purse strings for federal struggling-school funds, including disbursements of $3.6 million that went to 10 rural schools not working with the turnaround program. Thomas concluded in a January 2020 report that “decisions to not collaborate and to not prioritize funding for (turnaround) schools were wrong.”

A spokeswoman for the state education department said Woods did meet with Thomas “multiple times throughout his tenure,” though noted “several instances” in which Thomas requested meetings with “extremely short notice” or “was unwilling to meet” with some of Woods’ staff. The spokeswoman also disputed claims that the state withheld federal funding to schools under Thomas’ charge, saying many of those schools did receive funding while some “were not federally identified” to qualify.

“The arrangement presented challenges largely due to lack of alignment and oversight,” said the state agency’s communications director, Meghan Frick. “Having fiscal and legal responsibility for a program over which we did not have direct oversight or supervision put the agency in a difficult position.”

Meanwhile, some advocates wondered if the turnaround program was jogging in place. Meetings with an advisory group hinted at little progress as Thomas delivered what sounded like the same updates month after month, said John Zauner, executive director of the Georgia School Superintendents Association.

“There were certainly some red flags as time went on in the meetings,” Zauner said in a recent interview. “There wasn’t any moving the football down the field, if you will.”

Then came the audit of the turnaround program in late 2019.

Audit questions contractor pay

Ordered by Woods’ office, the audit identified about a dozen outside contracts at the turnaround office that rounded out to two years’ worth of about $1.3 million, nearly a third of the office’s total spending through mid-2019.

Auditors questioned why some consultants secured contracts that roughly doubled their daily pay rates from $500 a day to $900 or $1,100, while invoices they submitted appeared to give vague descriptions of what work was actually done. The audit also probed whether Thomas improperly influenced the state’s contracting process to pick certain consultants, resulting in a method that the Georgia inspector general’s office later concluded was faulty.

“Overall, it appears that the Chief Turnaround Office was mismanaged and that policies and procedures in place were routinely ignored by (Thomas),” the inspector general’s office said in a letter from January 2020.

Thomas strongly objected to the audit’s findings in two lengthy formal responses, calling it “a biased and unfair account” that aimed to do away with his program entirely. Notably, the auditors did not seek interviews with himself or many of the program’s key staff, Thomas said. He provided documentation showing the contractors in question put in bids that sought thousands of dollars less in daily pay than those submitted in competing bids. He also pointed out that contractors’ work was tracked in regular progress reports and performance reviews from local school officials.

As for contractors’ pay, Thomas said some outside consultants were tapped to kickstart the program’s work in the middle of the 2017-18 school year, before the program had time to flesh out its finance staff. Those consultants later formally rebid on contracts once their initial terms were up, leading to higher compensation amounts, he said. Thomas also denied influencing the contractor-selection process, chalking the accusation up to allegations from some disgruntled staff. He noted the audit found no evidence beyond hearsay that he or anyone else had improperly influenced picking contractors.

Overall, Thomas argued the audit served only as ammunition to dissolve the turnaround program and justify his removal. He sought to block the audit’s public release in court, claiming it could damage his prospects for finding future employment after he resigned.

“The audit appears to have been a retaliation to my efforts to promote collaboration and a smear campaign to harm me and the Chief Turnaround Office,” Thomas said.

Contracts were not the only source of tension. Some turnaround staff claimed they weren’t reimbursed for travel expenses while other staff and consultants were, including one specialist who argued in a lawsuit that she was wrongly denied travel pay to work in Macon-Bibb County schools. Thomas countered that he followed rules set by the state’s travel policy for all agencies when making decisions on travel pay, noting the education department did not have an internal policy on the subject.

Other lawsuits have come from Daryl Fineran, a former specialist in the turnaround program who filed a whistleblower complaint about the contracting practices. He claimed consultants took home larger pay for less work than regular staff, triggering a lopsided workload that worsened the program’s political head-butting with the state agency.

“Bottom line, it was all done in good faith hoping to help failing schools,” Fineran said in a recent interview. “They just hired the wrong person to run it.”

Rather than replacing Thomas, state school officials chose to phase out the turnaround program entirely. Some of its staff were hired by the state school-improvement division, which was already working with nearly 190 other struggling schools throughout the program’s tenure. Then, lawmakers axed the turnaround program’s budget in June 2020, about six months after Woods assured the General Assembly that his agency could absorb the program’s loose ends without any hiccups.

“I don’t foresee we will miss anything at all with that,” Woods told state lawmakers during budget hearings in mid-2020. “In fact, I think we will probably be stronger.”

Amid the controversy, Thomas maintained that schools under his turnaround program outperformed many other struggling schools in the state, particularly in some rural areas where students have long stumbled with test scores and general academic improvement. He also stressed the program’s importance, noting that many of Georgia’s elementary and middle schools continue to rank in the bottom half among schools nationwide in reading, math and science scores even as the turnaround program got underway.

“We have assisted schools and districts in creating the conditions for ongoing success,” Thomas said in a statement accompanying his resignation. “Ultimately, the State of Georgia needs to decide how to improve the outcomes that it is presently getting in education.”

School improvement moves on

For many local advocates and educators, the fate of the Chief Turnaround Office is a cautionary tale on the pitfalls of injecting politics and quick-fix solutions into the hands-on work that comes with helping Georgia’s neediest students.

This upcoming school year, state officials are set to distribute nearly $24 million in federal grants to around 230 schools statewide for improvement purposes such as teacher training, outside specialists, data tools, after-school programs and books. Many of those schools have stayed among the state’s lowest test scores and graduation rates for years.

Since the turnaround office’s closing, some of its former staff have taken jobs at local schools and districts. Others have become consultants or are retired. Only a few have remained at the state education agency to continue working with local districts and regional groups to give struggling schools a boost.

“No matter who does it, to me the work of school improvement is work that every school should do,” said Alexander, the former turnaround specialist team’s leader. “It’s difficult work.”

With the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting classroom teaching and test scores for more than a year, state and local school officials could use all the help they can get to ensure students at already low-performing schools do not fall through the cracks.

As Clayton County Public Schools’ superintendent, Morcease Beasley oversees three schools stuck on the state’s low-performing list for the last few years. The lack of standardized test scores during the pandemic has made it difficult to track those schools’ progress, he said. But Beasley’s schools still face significant challenges, even if they earn good enough scores to remove them from the state’s list. Just a fraction of students in his district received pre-kindergarten instruction, leaving them a step behind other parts of the state in reading and math proficiency, he said.

No matter what the state or a special legislature-created office may do, Beasley and other educators agree the burden is on local school administrators themselves to help their students turn a corner for the better.

“At the end of the day, we’re more interested in ensuring that all our students are getting what they need to be successful,” Beasley said. “Whether you’re on a state list or not, we’ve got to do it in order to get where we want to go.”

NOTE: This story has been updated to clarify the timing of Eric Thomas’ resignation, the jurisdiction of the internal audit, scope of a lawsuit from a former staff specialist and Thomas’ formal response to his management of travel reimbursements.

What else would you like to know about Georgia’s public schools? Share your thoughts/tips by emailing [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header image: Students in a classroom. (Credit: iStock)

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …

2 young Democrats win Statehouse seats as Republicans hold majority

ATLANTA — Many Statehouse incumbents appeared to beat back challengers Tuesday, ensuring their return to the Capitol in January. Republicans retain control of the House and Senate. Two Generation Z candidates will join the 236-member Legislature as new members of the House of Representatives: Democrats Bryce Berry and Gabriel Sanchez. Berry, a 22-year-old Atlanta middle …

Election night 2024: What to watch for as the results roll in

It’s been a long time coming, but we’ve finally made it to Election Day 2024. Today’s most anticipated race is, of course, the presidential contest between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump. The pair have spent a combined $25 million in new media ads alone in the past two weeks in this …