Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo‘Come after our children and we’ll come after you’: State moves to crack down on gang recruitment

Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens, Atlanta Police Chief Darin Schierbaum, Georgia Gang Prosecution Unit Section Chief Cara Convery, Attorney General Chris Carr and Gov. Brian Kemp join state and federal officials and law enforcement officers at a meeting of the Georgia Anti-Gang Network in Atlanta on Feb. 7, 2023, which focused on disrupting the recruitment of children and young adults into gangs. (Credit: Office of the Governor)

The Gist

State officials are seeking to disrupt criminal gang activity in Georgia through legislation that would require stiff mandatory minimum sentences for gang members who recruit other people, and especially children, into their gangs.

This comes at a time when violent crime is increasing across Georgia and local and state leaders are looking for solutions. But some lawmakers and human rights advocates say that harsher penalties will not curb gang-related crime, and urge legislators to address the underlying problems that lead young people into gangs and criminal activity.

What’s Happening

Last month the Senate passed an update to the Street Gang Terrorism and Prevention Act, calling for mandatory minimum sentences of five years for anyone who encourages, solicits or recruits another to become a member of a criminal street gang or to participate in gang activity. The bill, SB 44, has even harsher penalties for those who recruit a child under the age of 17, or someone who is disabled: 10-year minimum sentences for the first conviction, and 15-year minimum sentences for any subsequent convictions, with no possibility of probation or parole.

In presenting the bill to the Senate Judiciary Committee, its sponsor, Sen. Bo Hatchett, R-Cornelia, said he was doing so “on behalf of Gov. Brian Kemp, who has made tackling street gangs a priority” due to “the rising occurrence of gang members targeting children for criminal street gang recruitment.”

At a meeting of the Georgia Anti-Gang Network in Atlanta last month, Kemp said, “We’re making clear to gangs all across Georgia: Come after our children, and we will come after you.”

Hatchett said an investigation into gang activity in north Georgia that resulted in the indictment of 17 alleged members of the 183 Gangster Bloods in Barrow County last November found that “among other crimes, gang members were recruiting children using family-friendly events.” The attorney general’s office has reported that a block party organized by the gang, whose members are charged with murder, armed robbery and trafficking fentanyl and methamphetamine, used a bouncy house and an ice cream truck to recruit children into their criminal activities.

“Gangs are in the business of making money, and the lifeblood of their organization is recruitment,” said Hatchett, who observed that the reason gangs are trying to recruit young people is “they’re not as obvious a target for law enforcement officers, they can carry out the missions of the gang, and their penalties will be less. So you can send a 14-year-old kid to go rob several cars or carry drugs on their person, and they’ll be out in a couple of days. Whereas, if they’re older they’ll stay in longer.”

In advocating for the bill, Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) Executive Director John Melvin said, “What I’ve seen in the four years that I’ve been with the bureau is a logarithmic increase in the number of gang cases that the bureau is working and in gang problems statewide.”

Melvin noted that the legislation “gives the keys to the kingdom for a defendant willing to help the state.” A provision in the bill allows judges to lighten or suspend sentences for people convicted of recruiting adults into gangs, if they provide aid that results in the arrest or prosecution of fellow gang members or criminal accomplices. “It says, ‘Alright, if you want out from these mandatory minimums, then you help the D.A.,’” Melvin said.

Opponents of the bill point out that the “snitch” provision does not apply to people who recruit children into gangs, and that Georgia law already provides substantial penalties for recruiting minors into gang participation. They express concern that mandatory minimum sentences would unduly punish youth and young adult offenders caught up in gang life.

“We already have sentencing of five to 20 years” for gang recruitment of children, said Mazie Lynn Guertin, executive director of the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (GACDL). The key difference, she said, is that those laws “allow for judicial discretion. With this, the judge’s hands would be tied.”

“This bill will not stop individuals from preying on young, vulnerable children,” she said. “Instead it seems it will disproportionately harm teenagers and harm siblings … Oftentimes people join [gangs] coming from unstable homes or economic instability [and] they get a younger sibling to join. We know that in our system 17-year-olds are adults, so who’s going to be prosecuted is the 17-year-old adult who recruits their 14-year-old little brother.

“… This is going to be young people recruiting young people, and we’re going to talk about it like it’s a bunch of adults behaving badly, but every one of these people is under 25 years old. We’re going to think of them as predators, but really they’re just children themselves,” said Guertin.

During the Senate floor debate, Sen. Derek Mallow, D-Savannah, expressed concern about the “unintended consequences” of the bill, which he said could land young people who have otherwise not broken any laws in prison for engaging in self-preservation by joining a gang.

“I don’t know if you’ve ever been in poverty or impoverished or had the opportunity to live in the neighborhood that I grew up in, but there’s an opportunity in a gang, and that’s protection,” Mallow said. “If there’s a neighboring gang across the street, you better pick a side to be on because … that might determine life or death for you that day.”

GBI Special Agent in Charge Ken Howard, who oversees the GBI’s Gang Task Force, told State Affairs, “We in law enforcement, whether it’s within the Gang Task Force, or judges and prosecutors around the state, get in the game and use discretion. We’re not charging low-level actors with Gang Act crimes. We frankly don’t have time. We target the worst of the worst.

“We’re not going after that 18-year-old dude with no record who recruited somebody, or the kids on the corner in the city selling a dime bag of marijuana,” Howard said. “We recognize that they’re just cannon fodder for the older, smarter, higher-level members of the gang who are using them in their criminal enterprise. … We don’t want to bury that kid in a [correctional] system that may very well make him more of a predator, or more of a problem, than he already was.”

Why It Matters

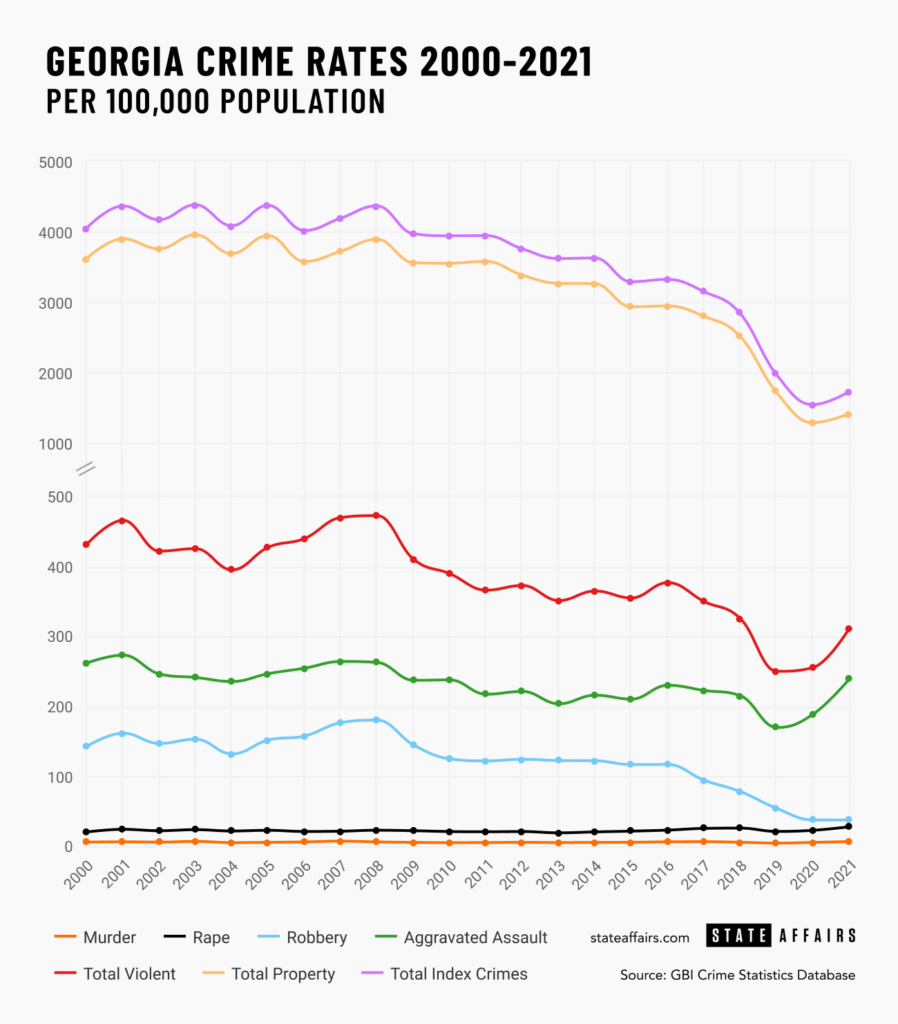

While overall crime in the U.S. and Georgia has decreased markedly over the past 20 years, violent crimes have increased in both urban and rural areas of the state in the last three years. Murders, rapes, and aggravated assaults have risen, while robberies and most property crimes have declined.

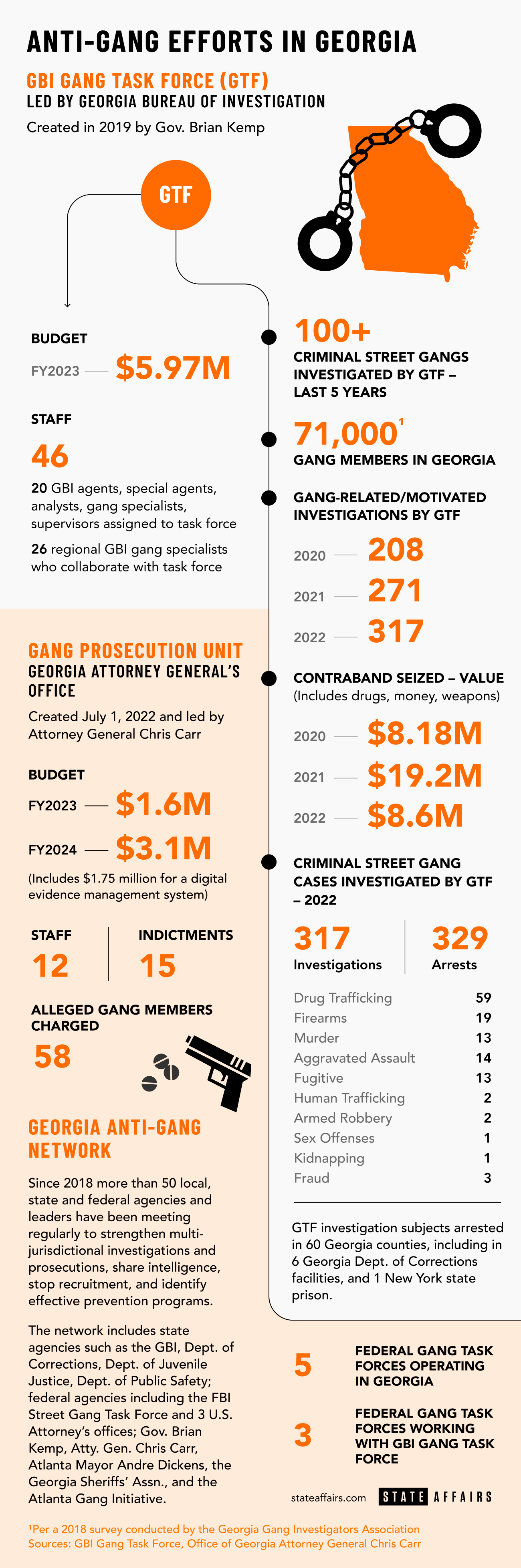

Attorney General Chris Carr and other state officials attribute 60% of violent crime in the state to gang-related activity. Citing their own data and a 2018 survey of county and state law enforcement agencies by the Georgia Gang Investigators Association, the GBI reports that at least 100 criminal street gangs and 71,000 gang members are active in the state.

According to the GBI, the number of gang-related investigations led by the 20-member GBI Gang Task Force has increased from 208 investigations in 2020 to 317 investigations in 2022. In that period, they’ve seized $36 million in contraband — mostly drugs, weapons and money, in cases involving 44 death investigations, 115 drug trafficking investigations and eight human trafficking investigations. Several of its big busts last year targeted gang members running organized crime rings out of six Georgia prisons and one prison in New York.

The budget of the Gang Task Force has grown from $1.7 million in 2020 to almost $6 million in 2023.

“Criminal street gangs in Georgia are part of large, multi-billion-dollar enterprises, affiliated with national gangs like the Bloods and Crips, and prison gangs that have tremendous authority over the guys running the streets,” said Howard. “Many of them tie back to criminal cartels in Mexico. What we’re dealing with is organized crime, no different than what mafia families were doing in New York. Everything they do is for money, and their pursuit of it fuels other crime, and violence follows.”

The 12-member Gang Prosecution Unit in Attorney General Chris Carr’s office was created in July of 2022 to take on the surge in gang-related crime. Since then, it has charged 58 people with crimes including murder, racketeering, drug trafficking, human trafficking, armed robbery and fraud, and secured 15 indictments.

The Gang Prosecution Unit is seeking to more than double its budget from $1.3 million in fiscal year 2023 to $3.1 million in fiscal year 2024, mostly to pay for a $1.75 million digital evidence management system that it says will help prosecutors to store and process data and video evidence, such as video from body cameras of police officers and law enforcement vehicles, and surveillance video from municipal, business and private sources, including hotels, airports and doorbell cameras.

Violent crime is an escalating concern in Atlanta, where for the third straight year the number of homicides increased. The Atlanta Police Department investigated 170 homicides last year, the most since 1996.

The uptick in violent crime has reenergized the movement among some residents of Buckhead in north Atlanta to secede from the city of Atlanta, an effort that resurfaced in the Legislature again this year. Its proponents cite high crime rates and violent incidents in Atlanta as a top concern. (Two bills related to Buckhead cityhood failed in the Senate last week).

One such violent incident occurred last November, when a shooting on the 17th Street Bridge in Midtown killed 12-year-old Zyion Charles and 15-year-old Cameron Jackson. Investigators charged three teenagers with murder in that case, including a 15-year-old and 16-year-old who were students at Atlanta Public Schools. Both youth were charged with two counts of murder, aggravated assault and violation of the gang statute, police said.

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, who is currently prosecuting the high-profile murder and racketeering case against Atlanta-based rap star Young Thug and two dozen other alleged members of the YSL (Young Slime Life) gang, called gangs “the number one threat against public safety” in Atlanta last year. She said gangs “are committing conservatively 75 to 80 percent of all the violent crime that we’re seeing within our community. And so they have to be booted out of our community.”

After another shooting last December that claimed the lives of a 14- and 16-year-old, an exasperated Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens said in a press conference that ending gun violence is a “group project … It takes every single one of us to counter this plague in our community — from city government, to our police, to our schools, to clergy, to parents and to young people themselves; we must pledge not to accept this violence as normal and do all that we can to end it.”

Some lawmakers and many youth and human rights advocates are calling for less incarceration and more community-based solutions to gun violence and gang-related crime.

“We have numerous opportunities to address the actual underlying issue of trauma, of poverty, of mental health … but sentencing people to be incarcerated simply because they participated in street gang activity does not make street gang activity go away, it doesn’t make our communities safer, and it doesn’t get us to the point of restorative justice, which makes communities whole,” said James Woodall, a public policy expert at the Southern Center for Human Rights.

“Bills like SB 44 do very little to address the reason why people may be compelled to engage in gang activity,” said Brian Nunez, a policy associate for the Southern Poverty Law Center. “Lengthy and costly mandatory minimum sentences do not appear to reduce crimes … The best way to make communities safer is by investing in them. Evidence-based studies show that community mobilization and social interventions are far more effective than harsher punishments in reducing gang-related activity.”

One such evidence-based approach touted by criminal justice reform advocates is the Comprehensive Gang Model developed by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, which relies on a coordinated strategy between law enforcement and educational and community groups to positively engage youth and others at risk of gang involvement. It has proven successful in reducing gang-related crime in several cities where it has been implemented, including Los Angeles, Richmond, Houston and North Miami Beach, according to the National Gang Center.

During the Senate Judiciary Committee discussion of SB 44 last month, Sen. Bill Cowsert, R-Athens, asked GACDL’s Guertin, “If this doesn’t help, what do you suggest? We’re dealing with a proliferation of gang activity, recruitment of young kids. What other tools do we have other than to get these people off the street? We’ve tried the rehabilitation route, we’ve tried three strikes you’re out, we’ve tried harsher penalties. If you were up here, what would you do to try to solve this problem?”

“I would be talking to my colleagues on the education committee, on the multiple health committees,” Guertin replied. “The issues that bring us here … it’s a lack of advantage, on any number of fronts — housing, education, access to employment — I just don’t believe that carceral measures are going to be the answer to any of this … Like you said, we’ve done this. We’ve done three strikes. The money is not being spent on the collateral matters that draw a child into a place where they find identity and camaraderie. It’s broken and it’s backward, but that’s what they’re finding there … in gangs. We’re not offering them much else.”

What’s Next

SB 44 was passed by the Senate on a 31-22 party-line vote, with most Republicans voting for it. The bill now awaits consideration in the House Judiciary Non-Civil Committee.

Have questions, comments or tips about gang-related activity or ways to curb violent crime in Georgia? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @JOURNALISTAJILL or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Related:

Why is Georgia spending millions on a task force to fight criminal gangs? (State Affairs)

Profile: Georgia Bureau of Investigation Director Michael J. Register (State Affairs)

Meet Chris Carr: Georgia’s attorney general eyeing reelection (State Affairs)

Header image: Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens, Atlanta Police Chief Darin Schierbaum, Georgia Gang Prosecution Unit Section Chief Cara Convery, Attorney General Chris Carr and Gov. Brian Kemp join state and federal officials and law enforcement officers at a meeting of the Georgia Anti-Gang Network in Atlanta on Feb. 7, 2023, which focused on disrupting the recruitment of children and young adults into gangs. (Credit: Office of the Governor)

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …