Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoSea turtles thrive, shorebirds take a dive in this year’s coastal ecosystem report card

Nesting loggerhead turtle on Ossabaw Island, Georgia (Credit: Georgia Department of Natural Resources)

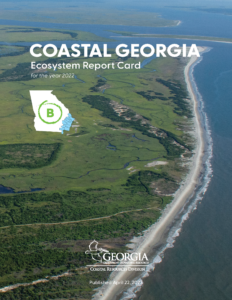

Shorebirds took a hit from predators and flooding, sea turtles were prolific, and blue crabs — feeling salty — fled the scene. These are a few of the findings in the Coastal Resources Division (CRD)’s annual Coastal Georgia Ecosystem Report Card released Saturday.

What’s happening

Every year since 2014, the CRD team at the Department of Natural Resources checks in on 12 indicators of coastal ecosystem health that impact humans, fisheries and wildlife, and issues a report card. Based on data collected in 2022, Georgia’s coastal ecosystem in this year’s report earned a B, which the CRD says equates to a “moderately good health score” of 74%, down from last year’s score of 81%.

The ecosystem indicators and scoring methods for the report card were developed with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, which has helped to develop other ecosystem health assessments around the country.

The species driving the ratings down a bit this year include birds that live along the coast, including wood storks and American oystercatchers. Their nests and hatchlings were preyed upon by raccoons and wild hogs, said Jan MacKinnon, a wetlands biologist who leads the Coastal Resources section. And flooding from heavy storms whisked away some eggs.

Most of the fish and shellfish did well, including red drum, sea trout and shrimp. But blue crab scored poorly. CRD Director Doug Haymans said lower levels of rainfall caused increased salinity in the water, likely driving blue crabs to less salty areas in the sea and marsh away from their sampling stations.

Loggerhead sea turtles scored an A, with a record number of 4,069 nesting sites located by DNR staff and volunteers. Wildlife biologist Mark Dodd said the once-endangered, now-threatened sea turtle species has made a comeback from a low of 385 nests 20 years ago. He credits plastic screening around nests to keep away predators and the proactive hunting and killing of raccoons, hogs and coyotes by DNR staff.

Dodd said they’ve also done well in educating the beach-going public to leave sea turtles and their nests, usually tucked into sand dunes, alone and to keep track of their dogs, who sometimes maul tiny turtles making their way to the sea.

The water quality index got an A this year, which means “it is generally safe to swim and to eat local shellfish, and that there are oxygen levels that support fish and other species,” according to the report. Bacteria were found to be at low levels, which is good news for oyster and crab fisheries and local restaurants serving raw oysters.

While bald eagles, another endangered species, aren’t usually included, the report notes some unusual sickness and mortality for eaglets on the coast. While their statewide survey found a record number of 229 occupied bald eagle nest territories, less than half of 73 nests on the coast fledged at least one young eaglet, falling short of the 80 eaglets the coastal area normally produces. A few adult eagles found dead in their nests tested positive for avian flu virus, and wildlife biologists suspect they were infected by preying on sick waterfowl.

Why it matters

The annual monitoring of key ecosystem indicators helps the scientists at DNR to see patterns and trends over time, and to understand what wildlife species are fair game for commercial and recreational fishing, and which animals and elements of the coastal salt marsh need protection, restoration and management, said Haymans.

The close to 400,000 acres of coastal marshlands located behind Georgia’s barrier islands comprise one of the most extensive and important marshlands in the U.S. They teem with life and nutrients, nurturing juvenile fish, shrimp, crab, turtles and many other marine species, filtering carbon pollution and sediments, and serving as a buffer against offshore storms and tidal flooding. In so doing, the marsh acts as both an environmental protector and an economic engine for the region.

The tidal flooding that’s threatening some shorebirds like the American oystercatcher is part of an ongoing process of sea level rise and warming waters brought on by global climate change. MacKinnon and her team in the Coastal Resources program are focused year-round on studying the marsh and developing ways to mitigate some of the harm caused by storm events and tidal floods, including coastal erosion and the destruction of wildlife habitats.

(Credit: Steve Pennings/Georgia Coastal Ecosystems/University of Georgia)

One coastal intervention that CRD is heavily involved with is the promotion of living shorelines, which uses native vegetation and bioengineering to stabilize shorelines.

Wetlands biologist Meghan Angelina leads a team that works to educate residents, and public and private organizations on why and how to install natural barriers like tall cordgrasses and oyster shells in lieu of wooden seawalls and granite bulkheads along the banks of tidal estuaries and rivers of the marsh. Such hardened barriers don’t allow the marsh and all its inhabitants to migrate inland as sea levels rise, movement that will become increasingly important over time.

Haymans said he hopes the strong showing for red drum in this year’s report will help to allay concerns about overfishing. Some fishing enthusiasts and environmental groups such as One Hundred Miles along the coast have been concerned that the state’s catch limit of five red drum is too liberal, and so CRD proposed a new rule limiting the catch to three fish last year, which produced outcry among others.

(Credit: Georgia Department of Natural Resources)

“The fishery is not actually undergoing overfishing,” said Haymans. “It’s cyclic and bounces around every year. But we were trying to be proactive in reducing the catch to three fish. And we ran into a little bit of concern amongst legislators … And so we’ve agreed to hold off until the next assessment is conducted in 2024 before deciding whether to move forward with that change or not. But we do have a 40% increase in the number of angler trips in the last 10 years, and our best guess is that’s only going to continue. And so with increasing fishing pressure, you can only assume it’s going to create more pressure on that species.”

The Coastal Resources Division has also been looking out for loggerhead sea turtles. While their nesting and hatching rates along the coast were prolific this year, they’re encountering a new potential threat from the federal government. In 2021 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed to start dredging shipping lanes along the Georgia coast year-round instead of holding off on that activity during the summertime when sea turtles nest and produce eggs in the dunes along the coast.

The adult female turtles, which don’t become sexually mature until they are 35 years old, rest on the beach after they lay a clutch of eggs and “spend a lot of time on the seafloor in the channels along the coast,” said Dodd, who added that dredging at that crucial nesting time could kill a number of mature female turtles, which would be a “huge setback” to the sea turtle population.

Haymans wrote a letter to the Corps protesting the plan, which said, “Certainly, we don’t want to lose any turtle any time of year, but killing nesting females is especially devastating to conservation efforts.”

The Corps issued letters in response, citing its need to consider multiple different endangered species in the Atlantic region, including right whales, and said that Georgia has no authority to block the decision about the dredging schedule approved by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Haymans told State Affairs that “30 years ago, the Army Corps agreed with protecting species, and with biologists who said that at least in Georgia, in the southeast part of the coast, dredging was best performed in the wintertime, when turtles were at their least occurrence here, and when risk to right whales was minimal.”

Federal judges have twice ordered a temporary halt to the dredging, and now a federal lawsuit against the Army Corps filed in the U.S. District Court in Savannah last December by One Hundred Miles is pending.

Haymans said the DNR is “still working with the Corps, trying to convince them that we need to maintain that 30-year history of dredging only during the wintertime. We don’t see the evidence of dredging’s impact on right whales. But we do see its evidence of impact on sea turtles. So this is an ongoing issue … and they have committed not to dredge this summer. And that’s as far as it goes. They are working on a draft environmental impact statement, for release sometime next year, which may support their desire to dredge in the summertime.”

What’s next

Scientists from the Coastal Resources and Wildlife Resources divisions of the DNR are already surveilling turtle and bird nests, testing the water and counting fish for next year’s Coastal Georgia Ecosystem Report Card.

In the meantime, Saturday (Earth Day) they’re showcasing their year-round conservation work as well as the environmental advocacy efforts of many other agencies, nonprofits, and wildlife enthusiasts at CoastFest, the annual outreach event held in Brunswick. It’s a free event with demonstrations that include a “touch tank” where visitors can handle shrimp, starfish and horseshoe crabs, and see a 5,000-gallon tank filled with native fish. Alligators, snakes, and tortoises will also be on hand, along with a birds of prey show featuring raptors — hawks, eagles and owls.

Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header image: Nesting loggerhead turtle on Ossabaw Island, Georgia (Credit: Georgia Department of Natural Resources)

Related: Q & A with CRD Director Doug Haymans: https://stateaffairs.com/georgia/qa/georgia-coastal-resources-division-doug-haymans/

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the fact that CRD Director Doug Haymans said that lower, not higher, levels of rainfall caused increased salinity in the water that impacted blue crab last year.

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …