Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoMeet the Head of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation

Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon (State Affairs)

- Playmaker: Vic Reynolds

- Role: Director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation

- Tenure: 2019 to present

Vic Reynolds leads the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI), overseeing a nearly $280 million annual budget, directed towards law enforcement, assisting local police with criminal investigations through resources such as the crime lab and funding the state’s medical examiners.

The GBI will also investigate officer-involved shootings and other serious police use-of-force incidents if it is asked to do so by a local police or sheriff’s department. The GBI also collects and reports statewide crime statistics and other law enforcement-related data.

Formerly the district attorney for Cobb County, Reynolds was appointed to the position of GBI director in 2019, shortly after Gov. Brian Kemp took office. A key project he has helmed is the state’s two-year-old Gang Task Force, an initiative promised by Kemp on the campaign trail.

State Affairs sat down with Reynolds for a conversation about his life, career and view of the agency he runs at the GBI headquarters in Decatur last week. His responses have been edited for length and clarity.

What is the professional path that led you to your current role?

Reynolds’ first job was working the newspaper delivery route in the small town of Rome, Georgia.

“I was raised out in that mill village and my mother was probably the encouraging voice to go to school, to get an education and to pursue college. I didn’t know what I wanted to do when I graduated from high school.”

He started off at his local junior college before saving money to transfer to Georgia Southern University where he earned a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice in 1979. He then returned to Rome where he became a police officer and married his wife of 30 years, Holly, with whom he has two daughters.

“I always wanted to be a cop, just something I wanted to do, and was able to go to work for the (Floyd) county police department.”

“Holly and I got married and she encouraged me to go to law school, and I had no intention of going, it wasn’t in my plans. I enjoyed law enforcement and wanted to stay in it but she encouraged me to pursue law school and so I lived in Rome the first year (of law school), worked as an investigator (for the district attorney’s office) and commuted to Atlanta three nights a week.”

“That was tough on a relatively new marriage. But she was very supportive and said: Vic, you need to go to school. It is a great opportunity, we can afford it, and I can support us during that time.”

Reynolds ended up leaving the DA’s office and earned his law degree in 1986 from Georgia State University’s College of Law, which had only recently been established.

“That’s kind of what got started, got me started in this drive.”

Was there a defining moment in your life or career that helped guide you to this role?

“It really was my wife Holly, she had encouraged me to look at law school … I was in the second class to be admitted to Georgia State Law School and graduating from that school, it opened up so many more doors to me than I ever even imagined growing up in Rome, Georgia.”

“From there I prosecuted in downtown Atlanta in the Fulton (County) DA’s office and prosecuted in Cobb where Holly and I were living then. From that position, I was just in the right place at the right time and got appointed chief magistrate judge. Young, 36-years-old, and running an office with about 55 people in it, I’ve just been so blessed about literally being in the right place at the right time. That’s how all of that career began.”

In addition to his wife’s encouragement, Reynolds said the decision to leave his job as an investigator for the DA’s office was also influenced by the election defeat of the DA he had been working for.

“I really learned about the dilemma of working in a political office, and sometimes that it doesn’t work out the way you want it to or the way you think it should. I was at a crossroads.”

What are your most major accomplishments at GBI so far?

“I’m proud of the work that we’ve done in investigating criminal street gangs in the state, it’s something the governor wanted to see done, and I think we’ve answered that call.”

“I’m also very proud of the work that we’ve done regarding investigating human trafficking. And we’re starting to begin looking at labor trafficking as well, we just made our first major case in that area within the last couple of months.”

“I also think we’ve done a really good job of pushing out information from the GBI to the public. We try to be very open and transparent … I’m proud of the way that we’ve handled very sensitive cases (such as) officer-involved shootings.”

“I think we’ve done a good job in handling cases like the (Ahmaud) Arbery case in Brunswick, how we responded to it. I think we did it in an efficient manner. I think we did it in a very open, transparent, candid manner.”

What challenges and criticism have you faced during your time in leadership?

“I think in this day and time, there’s probably no profession scrutinized as much as law enforcement. Some of it is warranted. I don’t think all of it is, but some of it is.

“The main thing that we do that probably benefits this agency is our willingness to tell the public what we are doing. And if we have proof to show them and we can show them videos of scenes, videos of officer involved shootings, things of that nature, the GBI wants that done. (Though) sometimes we can’t. Sometimes because of the nature of what the incident is or because perhaps one of our partners like a local prosecutor may not want a video out, then we’re a little bit limited in what we can do.”

“Something that I’ve tried to stand on professionally is: tell the truth, period. Tell the truth.”

To follow up, can you explain that challenge of working with local authorities on sensitive cases?

“Sometimes it may be more intense, like the situation in Brunswick (with the Arbery case), as opposed to something that may not have the media attention behind it.”

“We’re an assisting agency that has to be requested, and sometimes the public, either forget, or they just don’t know that. And the (public) reaction is: What’s the GBI doing? Why don’t they do something?”

“And you just want to yell as loud as you can: because nobody’s asked us to. And so, that’s something that that can be frustrating for us. Once we’re asked to do something we can do a lot. But again, we can’t just do it based on what we think is appropriate or what we think is right.”

“There’s always a balance, and I do believe that most crime has to be solved locally, the local law enforcement community has to solve crime in their area.”

What are your plans for what you want to accomplish going forward?

“One of the main functions of the GBI is our ability to do forensic science work for our partners: for prosecutors and law enforcement agencies around the state. They depend on us… and there’s a tremendous volume of requests that come to the lab and we must be able to prioritize, to say: this is what the best use of our resources would be. We need to really take a good deep dive into how we’re doing things in the lab, make sure that we’re doing it as efficiently as we can.”

Note: Crime lab resources — from DNA to ballistics testing — offered by the GBI to assist local agencies in their investigations are provided free of charge.

“We always need to find new ways to think outside the box to talk about the possibility of continuing or growing (resources) or outsourcing in certain cases. And I think that’s a big challenge for us here in the next few years.”

“I think we also need to continue to grow our ability to do officer involved cases. I wish we didn’t have any, I wish that never happened in the state… but we’re approaching 100 or so cases this year before it’s all over and I think we were at 96 last year. Those are cases that are extremely labor intensive, they require multiple agents, multiple crime scene folks. Our goal is to get those cases worked in a 60-to-90-day time frame.”

“Our main job is to enforce the law. That’s what we’re supposed to do, but you know we need to be good community partners as well. We believe in accountability courts, we believe in diverting people out of the system when possible, but as long as we balance that with our primary function.”

Who should we profile next in Georgia? Share your thoughts/tips by emailing [email protected].

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

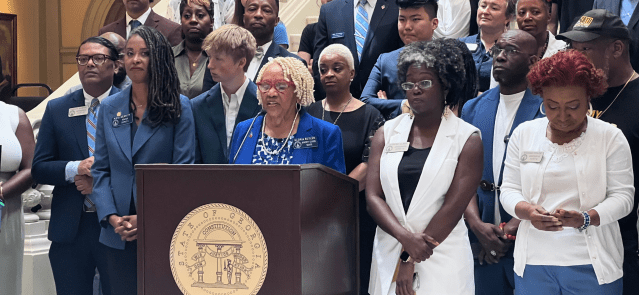

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …