Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoJustice Clarence Thomas’ Hard Right Conservatism Leaves His Hometown Perplexed

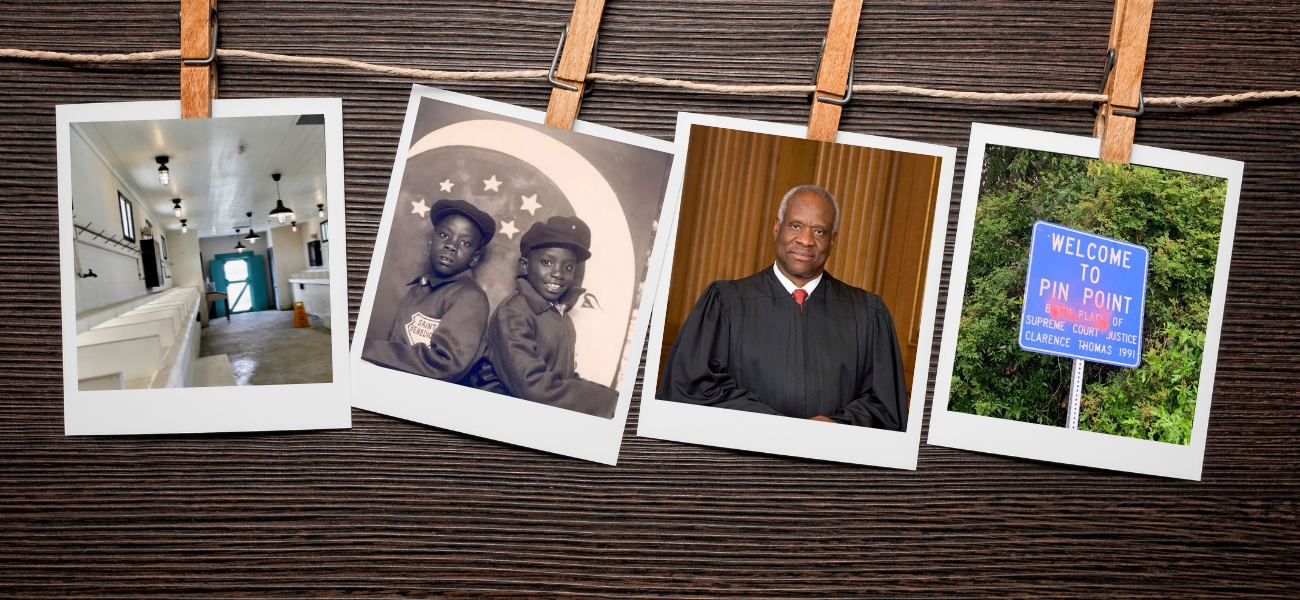

Credit: State Affairs composition, Cknight70

PIN POINT, Georgia – Amid the chinquapin and moss-draped oak trees that line Shipyard Creek, a sign at the sharp turn off State Road 204 welcomes visitors to the small unincorporated Chatham County community of Pin Point, the birthplace of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

In what might be seen as a possibly unintended nod to the controversy that often surrounds the Supreme Court’s most conservative justice, the Pin Point welcome sign marking the town as Thomas’ birthplace is marred by red spray paint.

In Savannah, where Thomas spent much of his childhood, the name plaque on the Savannah College of Art and Design’s Clarence Thomas Center was removed earlier last week amid outcry from students following the Supreme Court’s ruling to reverse the landmark Roe v. Wade right to abortion case.

A recent visit to Clarence Thomas’ hometown gives some insight into the man and his hard political lean right, voicing some views that have solidified the enigmatic justice’s reputation as the High Court’s most conservative judge.

“Black people are conservative in several areas … but that's a cultural thing. But politically, I'd have to say he's to the right of most people in Liberty County and Chatham County,” said Liberty County state Rep. Al Williams (D-Midway). About 12% of Black voters in Georgia identify as Republican, according to surveys by the Pew Research Center.

The entrance sign to Pin Point, Ga., is marked with graffiti in this photo taken in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

How Thomas came to adopt his views may appear counterintuitive to many. As a judge, Thomas is what constitutional law scholars call a strict “originalist” – meaning a belief that all statements in The Constitution should be interpreted literally and according to the understanding at the time of its ratification in 1789, when slavery in the U.S. was legal and widely practiced.

Thomas grew up in the segregated Jim Crow South, hailing from the poor, but tight-knit and culturally rich, Gullah Geechee people – descendants of West and Central Africans brought to the Carolinas, Florida and Georgia to work as slaves on rice, cotton and indigo plantations, according to the National Park Service. Over the past century-plus, the Gullah Geechee have maintained the heritage of the community, including its dialect and food traditions.

Few Gullah Geechee remain who remember the Pin Point and Savannah of Thomas’ childhood, and fewer still are open to talking about Thomas. “I’ve got nothing to say about Clarence Thomas,” was a common refrain when State Affairs visited the region.

Near Savannah, in Liberty County’s Sunbury community where Thomas spent many summers, 89-year-old Albert Greene Sr., a mechanic and cousin of Thomas', recalled knowing Thomas’ grandfather, Myers Anderson, who Thomas went to live with along with his grandmother at the age of 6.

“He was a tough old man,” Greene said, recalling that Anderson would often repeat the saying, “When you know the Lord, you’ve got power.”

Anderson was a prominent businessman in Savannah’s Black community. After he converted to Catholicism, Thomas joined the faith, setting him apart from the more prevalent Baptist beliefs of his kin.

“He [Anderson] took those two boys {Thomas and his brother] in and said they’d be serious men and not be sloppy,” Greene said. He and other neighbors said they could see few links to the Gullah community Thomas hailed from that would explain his political views.

Albert Greene Sr. stands outside his home in Pin Point, Ga., in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

“You think Clarence is conservative? His granddaddy made him seem moderate,” said Williams, who also knew Anderson.

Myron Magnet, author of “Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution,” a 2019 book that analyzes Thomas' jurisprudence, said, “His grandfather taught him that his fate was in his own hands, and despite that America was a racist country, there was the opportunity to forge his own path.”

Magnet added that Thomas had a “second conversion experience and realized his grandfather was right” when Thomas attended a protest against the Vietnam War at Harvard Square in 1970 that turned violent. The experience left Thomas feeling “appalled, and feeling rage and hatred,” Magnet said.

After graduating Yale Law School, Thomas continued to question liberal policies aimed at improving racial inequities through the lens of the “Emersonian self-reliance” of his grandfather’s worldview, said Magnet, referencing the 19th Century writer Ralph Waldo Emerson. “It was individualism squared,” Magnet said.

The Pin Point Heritage Museum located in Pin Point, Ga., is shown in this photo taken in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

A Catholic Upbringing

Following the 6-3 Supreme Court reversal of Roe v. Wade, Thomas, in a concurring opinion, went further than the majority opinion. He took aim at the landmark cases that protect same-sex marriage and access to contraception and that make it unconstitutional for states to criminalize sodomy or oral sex.

“[W]e should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell,” Thomas wrote, adding: “After overruling these demonstrably erroneous decisions, the question would remain whether other constitutional provisions guarantee the myriad rights that our substantive due process cases have generated.”

State Rep. Williams, a 74-year-old, 1960s civil rights activist and himself of Gullah heritage, didn’t mince words when talking about Thomas’ political views: “The only thing he took with him was his skin,” Williams said.

Thomas, through Supreme Court staff, declined requests for an interview or to comment for this story.

State Rep. Al Williams stands outside the Dorchester Academy in Midway, Ga., in this photo taken in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

Thomas’ Catholic upbringing and private Catholic education at St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Church in Savannah, have a lot to do with how Williams and Thomas – despite hailing from similar cultural backgrounds – came to such different political positions, said Williams. “He was very sheltered,” Williams said, recalling that Thomas' grandfather held conservative views far different than those of the Black community at the time.

Despite their political differences, Williams recalled meeting Thomas in person a few times. Williams described Thomas as pleasant with a great laugh, and as a person who ”enjoyed a cigar.”

In support of Thomas’ 1991 Supreme Court nomination, Williams organized a bus of 50 to 60 people from the community to drive to Washington, D.C., and lobby senators to support the appointment. Williams, whose politics “could not be further to the left if I ran,” he said, now regrets that level of support, a feeling he thinks is shared today by all but a rare few people on that bus.

And even other passed-down memories are harder for some to shake.

A boat sits in marshlands near the Pin Point Heritage Museum in Pin Point, Ga., in this photo taken in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

Taylor Washington, 45, recalls a childhood memory of her late grandmother, Pin Point native Emma Ree Wright, that forever defined her view of Thomas.

To celebrate Thomas’ 1991 ascension to the court, Washington said Pin Point residents organized a party in Thomas’ honor at the local community hall. On the evening of the event, her grandmother took a limousine from Savannah to Pin Point for the festivities. “They threw one of the biggest bashes ever; it was something to remember,” Washington said. “It was like: Yes! One of our own has made it to the Supreme Court. Just everybody was ecstatic, everybody was happy, there was overwhelming joy.”

Except, Thomas didn’t show.

“I can remember sitting down in my living room. And we got into a conversation about it,” Washington said, recalling that moment with her grandmother. “And she said it hurt. Those were her words: ‘Clarence Thomas hurt me,’ and then I don't think it was so much of just her personally, I think she was speaking for everybody.”

The plaque commemorating Savannah College of Art and Design’s Clarence Thomas Center is shown missing in this photo taken in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

'No Hero Here'

Thomas’ Supreme Court nomination was contentious when allegations of sexual misconduct against him emerged and the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, helmed by then-U.S. Sen. Joe Biden, heard compelling testimony from Anita Hill, who was attorney-advisor to Thomas when he served as assistant director of the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights in 1981. Thomas was resolute in his denials of the sexual misconduct allegations, famously calling the proceedings a “disgrace” and a “high-tech lynching.”

Thomas also referred to the experience as a “living hell” to which he would prefer assassination. Today, many wonder whether the experience, perhaps mixed with resentment, further hardened Thomas' already conservative views.

The assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and racist remarks about King that Thomas has said he recalls hearing in seminary school, led Thomas to stray from conservatism and Catholicism for a time, to the outrage of his grandfather. It’s a chapter of his life he has spoken about in numerous lectures, and written about in his memoir.

While a student on scholarship at Holy Cross, Thomas participated in progressive activism and met his first wife, Kathy Ambush, who grew up middle class in Worcester, MA.

Magnet, who has met with and maintained correspondence with Thomas since 1994, said Thomas’ concurring opinion overturning Roe V. Wade, is “not at all surprising” when looking at past opinions, in which he has routinely criticized the concept of substantive due process which provides for rights such as abortion access and same-sex marriage, among others.

Besides a mention on the road sign, and a historical marker in town, there are few traces of Thomas in Pin Point. At the Pin Point Heritage Museum, built on the site of the crab and oyster cannery where Thomas’ mother and much of the local Gullah community worked between 1926 and 1985, Thomas makes a cameo in a 35-minute documentary for visitors to watch before touring the site.

The crab factory where Justice Clarence Thomas' mother worked is housed in the Pin Point Heritage Museum in Pin Point, Ga., shown here in this photo taken in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

He speaks about the poverty of the place and playing outdoors because of the heat. He mentions his nickname there was “Boy” and his brother Myers was “Peanut.” An engraved slab commemorates Myers, who died in 2000, and was, according to Thomas' memoir, a Democrat.

Towards the end of the video Thomas analogizes America to a quilt, with Pin Point’s Gullah Geechee being a patch in it, before making an appeal to patriotism. “Slavery and discrimination and segregation tatter the American experience, but it’s still our experience,” Thomas says in the video.

While there is a certain amount of respect and pride that a fellow Georgia Gullah Geechee ascended to the Supreme Court, his political views “are an enigma,” said Williams, the state lawmaker from Liberty County.

Back in Liberty County, standing on the porch of the Dorchester Academy – once the primary site of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Citizenship Education Program, an incubator of a generation of civil rights leaders, and where a young Williams spent his summers before being drafted to fight in Vietnam, Williams remarked on Thomas’ notable absence from the Dorchester Academy, now a museum.

“What favorite son from Savannah to Liberty County would have ascended to the Supreme Court, and you won't find one picture of him in a Black museum or anything Black – who else would that have been?” Williams said before pausing and shaking his head. “No, no, no. No hero here.”

An American flag flies of marshlands near the Pin Point Heritage Museum in Pin Point, Ga., in this photo taken in June of 2022. (Credit: Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon for State Affairs)

Join The Conversation

What else do you want to know about abortion restrictions and state government in Georgia? Share your thoughts/tips by emailing [email protected].

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

Rural communities hopeful Kemp change to state soil amendment law will curb stink

After seven years and millions of dollars in restoration, Heritage GA opened its door last month to those seeking solitude and a chance to commune with nature. But the constant presence of trucks hauling a noxious concoction of waste byproducts from poultry processing plants threatens to ruin those plans. The historic Catholic retreat sitting on …

Watch live: Kemp signs $36.1B budget bill

Today is the deadline for Gov. Brian Kemp to either sign or reject bills passed by the Georgia General Assembly during this past legislative session. Arguably, the biggest of those bills is the annual budget. Kemp and first lady Marty Kemp will be joined by Lt. Gov. Burt Jones, House Speaker Jon Burns, and members …

Bill adds violation to Soil Amendment Act, but will it stop the stench?

After years of enduring intrusive, foul-smelling waste spread on untold tracts of rural land, Georgians living near such sites are finally getting some relief. On Monday, Gov. Brian Kemp signed into law a bill that adds a new violation to the state’s 48-year-old Soil Amendment Act. Soil amendment is meant to help farmers create healthier …

House speaker Jon Burns hires new communications director

House speaker Jon Burns, R-Newington, announced today that he has hired a new communications director. Kayla Roberson, who has served as press secretary at the Georgia Chamber for the past year or so, will now oversee all external communications, media relations and strategic messaging for Burns. “I’m excited to welcome Kayla to our team,” Burns …