Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoFood insecurity in Georgia is huge, and a Senate bill hopes to bring parties together to figure out how to fix it

Georgians experiencing food insecurity are seeking out free food from food banks at rates 20% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic. (Credit: Feeding America)

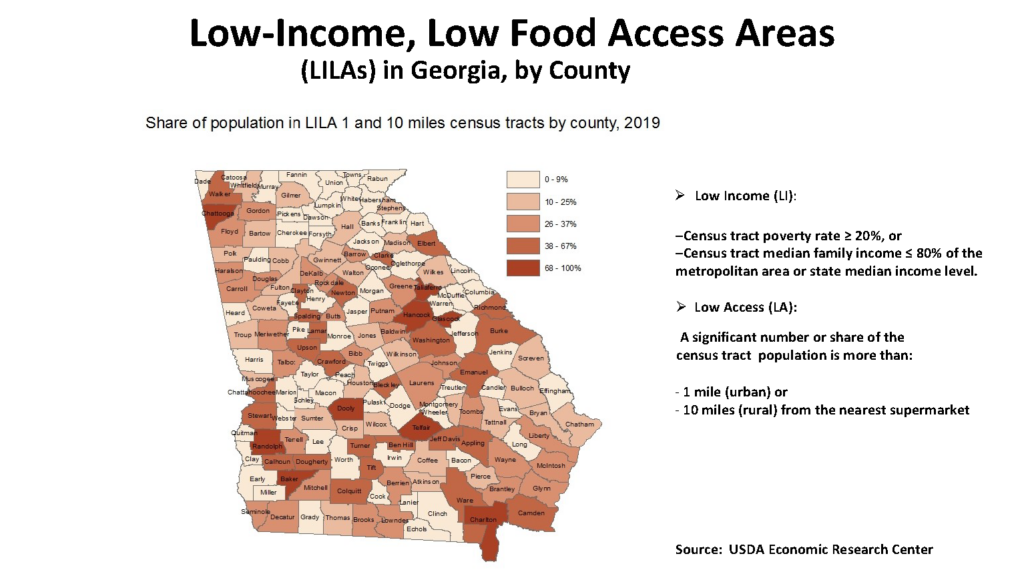

- Georgia is rife with food deserts. About 22% of the state’s 10.9 million residents live in an urban area that is more than one mile from a grocery store, or in a rural area more than 10 miles from a grocery store.

- There are concerns that rural areas are an afterthought for 'legislators, agencies and funders' regarding food security.

- SB 177, the Food Insecurity Eradication Act, will look at improving access to healthy foods and ending food deserts across the state.

A two-year effort to tackle food insecurity in Georgia may be coming to fruition. The General Assembly is now moving on SB 177, a bill to create a Food Security Advisory Council that would find ways to get more healthy food to economically disadvantaged people in underserved areas.

It began in early 2021, when Sen. Harold Jones II, D-Augusta, spurred by the closing of grocery stores in low-income areas of his district, pushed through legislation to set up a Senate study committee to look at improving access to healthy foods and ending food deserts across the state. As chair, he convened several meetings that fall, featuring major players in the food sector, including farmers, food bank execs, economic development experts and leaders of state and federal agencies that provide food and nutrition education to children, seniors and needy families.

“I thought that I could fix it, that we could do a bill on tax credits for grocery stores, and they’ll come running,” Jones told State Affairs. “And maybe we could do a deal with farmers’ markets to get more fresh food to places that don’t have it.”

What he learned was that the issues and market forces that make getting good, healthy food to the Georgians who most need it are “complex and layered.” For one thing, he said, he and other legislators “didn’t really understand the difference between food deserts and food insecurity, which you really have to get a grip on to have the kind of impact we hope to have.”

Food deserts, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), are areas where people have limited access to a variety of healthy and affordable food. Food insecurity is the consistent lack of food to have a healthy life because of your economic situation, driven by poverty, lack of affordable housing and chronic health conditions, among other factors.

“They’re integrally related, of course, but we have to grapple with both circumstances in order to make progress,” said Jones. “And what we’ve learned from the study committee is that we need to bring together all the experts and stakeholders who constantly deal with these issues, who don’t always agree with one another, and let them kind of work through it, and come up with solutions. And then we need to get some serious state buy-in on legislation, including funding, to solve these problems.”

Where’s the bread?

Georgia is rife with food deserts. About 22% of the state’s 10.9 million residents either live in urban areas that are more than one mile from a grocery store, or in rural areas more than 10 miles from a grocery store. And poverty factors heavily in the lack of food access. Alana Rhone of the USDA’s economic research department told legislators that Georgia has the sixth-highest share of low-income areas in the country where people also lack adequate access to groceries. More than 2 million people in Georgia, including 500,000 children, live in these low-income and low-access areas, located in both urban and rural areas across the state.

Food insecurity and consumption of nutrition-poor food, such as high-salt, high-fat foods, cost Georgia $1.78 billion in additional health care costs each year and increase the risk for a number of chronic health conditions, including high blood pressure, diabetes, kidney disease, osteoporosis, obesity and cancer, according to Joy Goetz, an expert with the Georgia Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Last week, when SB 177, the Food Insecurity Eradication Act, was discussed during the Senate Agriculture and Consumer Affairs Committee meeting, some of the strain among the various public and private entities whose leaders are likely to be appointed to the 15-member council to be created by the bill was apparent.

Jones discussed the need for the council to take up regulatory reform at some state agencies, including the Georgia WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program Women, Infants, and Children) program within the state Department of Public Health (DPH), which provides healthy food, baby formula and nutrition education to 185,000 participants each month. He said some grocery store operators reported that they were stymied in their efforts to open new stores in underserved areas due to stringent regulations and red tape that made them wait from a few months to a year to get a WIC license.

His observations were reinforced by Kathy Kuzava, president of the Georgia Food Industry Association, who said the profit margin of grocery stores and supermarkets is typically below 2% and that many store owners can’t afford to wait for months and miss out on revenue from WIC-related sales. She said the state WIC program’s policy of only issuing licenses at certain times of the year, and not issuing licenses to grocers until they’ve held a SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as Food Stamps] license for one year, were particularly burdensome.

Kuzava told State Affairs that “both SNAP and WIC are absolutely vital components to running a successful grocery store, particularly in regions where customers are low income. … If you’re trying to attract business, you want to be able to take care of 100% of your customers from day one. So if their customers have to shop somewhere else to use the benefits, they’re not going to get that store up and running like it should be.”

DPH Communications Director Nancy Nydam told State Affairs this week that “WIC no longer has a policy that requires grocery stores to have held a SNAP permit for at least one year or previous grocery industry experience for one year.” She said the current requirement “is in line with federal regulations that require the existence of a SNAP permit in good standing with the USDA Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) in order to be authorized as a Georgia WIC grocer.”

Tension between dollar stores and full-service grocery stores also emerged during the study committee sessions, and surfaced at the Senate Agriculture Committee hearing last week.

Tom Coogle, president of Reynolds Foodliner, which operates Piggly Wiggly grocery stores in many rural and low-income areas of Georgia, told legislators in 2021 that a “huge number of dollar stores opening up” was a threat to independent grocers who “are trying to draw from a larger footprint” in underserved areas, and that dollar stores offering milk and other food products cut into their business, which operates on a thin 1.75% profit margin.

Grocery store operators and economic development and nutrition experts continue to voice their concerns about the economic and health problems that dollar stores present. DeKalb County has maintained a moratorium on new dollar stores since 2019 in an effort to encourage grocery stores and supermarkets offering fresher, healthier foods to set up shop.

“There are only so many people in a small community,” said Kuzava. “And all those people want a large grocery store. But a community has to have enough business to support a large store. And grocers come in and do an assessment to see if there’s enough volume there. If there are too many stores close by selling food, whether it’s a dollar store or a drug store — because everybody’s in the food business now — a grocer doesn’t go into that area.”

Rurals outside Atlanta left to fend for themselves

Meanwhile, Deidre Grim, executive director of Forsyth Farmers’ Market in Savannah, said she is concerned that rural areas in general are an afterthought for “legislators, agencies and funders who are addressing nutrition security. It doesn’t trickle down to the coast like it needs to. It doesn’t go very far past Atlanta.”

Grim noted that their business provides a robust market for local farmers, generating $1.2 million in annual sales last year, including about $74,000 of food offered at half-price to SNAP customers. And while their mobile food truck serving hundreds of elderly and low-income residents in Chatham County currently receives $125,000 a year in federal USDA grant funding, “we don’t get a dime from the state.”

“We have a ton of agencies, organizations and nonprofits working tirelessly to make sure that Georgians have healthy food in their bellies, but due to a lack of coordination, we’re leaving a lot of money on the table,” said Dr. Amy Sharma, executive director of Science for Georgia, a nonprofit advocating for the responsible use of science in public policy, who spoke in support of the bill in a Senate committee last week.

“We have gaps in some places, overreach in others … How do we support our Georgia Grown farmers in getting food to people? How do we get people the funds to buy food? How do we educate people on what they want to eat? If they see a vegetable they’ve never seen before, it might be delicious, but let’s give them info on how to cook it. This bill addresses all these things.”

Danah Craft, the executive director of Feeding Georgia, part of a statewide network that includes eight regional community food banks, said she is hopeful the food security council can leverage the expertise on hand to come up with creative solutions to address food insecurity.

Demand at Feeding Georgia’s food banks is 20% above pre-pandemic levels, she said, “a function of the high inflation, food and fuel prices that people are experiencing right now that are really squeezing low-income families.” The organization’s food banks and more than 2,000 partner pantries distributed 127 million meals to food-insecure Georgians in 2019, 171 million meals in 2020 during the height of the pandemic emergency, and 161 million meals in 2022.

Craft said food banks are trying to help Georgia farmers, who last year donated more than 30 million pounds of fresh “ugly produce,” or misshapen fruits and vegetables not aesthetically pleasing enough for the retail market, to move their goods to local food pantries, mobile food trucks and other partner venues where people in need of fresh and free food can get it.

“There’s a lot of surplus food, and the issue is always that people are in one place and the food is in another. And how to move it quickly and safely into communities where it’s needed has always been the puzzle and the logistics challenge that food banks have placed themselves in the center of,” she said.

Craft said she hopes the state food security council, if it’s greenlighted, will look at promising state and federal programs that could be replicated and expanded. That includes a federal Farm to Food Bank program that currently provides a grant to states covering half the cost of packing and transporting food, which food banks have to match. The Georgia Department of Human Services recently won a $164,000 grant for that program, as well as federal funds from the American Rescue Plan Act that will pay for “last mile” distribution of fresh and perishable food, providing infrastructure like refrigerated coolers to food pantries, to keep food from spoiling before it can be delivered.

Craft credits Gov. Brian Kemp for putting $800,000 in the fiscal year 2023 and 2024 budgets to support the state’s Farm to Food Bank program, which provides funds for food banks to buy surplus food from Georgia farmers. The program has allowed food banks to offer premium produce to clients that normally isn’t donated, such as citrus, sweet corn and collard greens.

“If we can get the state and private entities to invest more in building out the capacity of our food network in areas that are hard to reach, that would be a great outcome,” Craft said.

Jones said he’s also interested to see if the council can come up with innovative ideas to transport food. He said a short-lived program that rideshare service Lyft offered in Atlanta in 2019 to take food insecure people to and from grocery stores for $2 per trip “caught my eye. That didn’t pan out, but I’d love for the council to look at it again.” (Doordash, it turns out, is now partnering with the Atlanta Community Food Bank to deliver food to local pantries and other community partners).

“The strategy behind the council is to bring together all these people and entities, public and private, that are active within different spaces in food insecurity, and to get these experts talking to each other, and drafting legislation,” said Jones. “They’ll also help us to direct funding, to make sure it’s going to the right places. And then we as a state government will have to step up and buy into what they propose to fix these issues.”

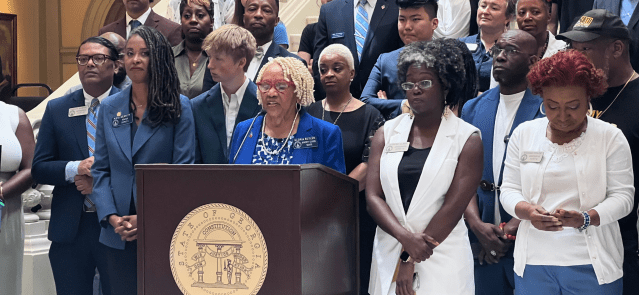

SB 177, the Food Insecurity Eradication Act, passed unanimously out of the House Agriculture and Consumer Affairs Committee on Tuesday, and awaits action in the House Rules Committee.

If the bill passes before Sine Die, the last day of the legislative session on March 29, and is signed by Kemp, the Georgia Food Security Advisory Council will be created within the Department of Agriculture and the governor, lieutenant governor and speaker of the House will be charged with appointing its 15 members.

Have questions, comments or tips about food insecurity or food access in Georgia? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on @journalistjill or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header image: Georgians experiencing food insecurity are seeking out free food from food banks at rates 20% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic. (Credit: Feeding America)

Related:

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …