Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoLawmakers asked to referee fights between cities and counties over local sales tax revenues

ATLANTA — Leaders of three Georgia cities pled their case to lawmakers on Monday for changes to the way some local sales taxes are divvied up between cities and counties. They said current law gives counties an unfair advantage in negotiating agreements and allows counties to hog tax proceeds — or at least to threaten to do so.

What’s Happening

At issue are the terms by which Local Option Sales Tax (LOST) agreements between cities and counties are renegotiated, which generally happens every 10 years after a new U.S. Census is conducted.

LOST proceeds come from a 1% tax on the sale of goods and services within a given county, which are split up between that county and certain cities within it to be used for services such as police, fire, water, waste disposal, and libraries.

In Georgia, 147 of 159 counties have such LOST agreements in place. Seven others have LOSTs dedicated strictly to education.

Just how counties and cities share those tax proceeds is at the heart of intense and often acrimonious debate that happens every time LOST agreements come up for renegotiation, as they did last year, said Rusi Patel, general counsel for the Georgia Municipal Association (GMA), during a presentation to lawmakers and others gathered for a Senate study committee meeting at the Capitol on Monday.

The state law defining how LOST revenues should be allocated includes eight criteria that both county and city leaders agree are vague and open to interpretation. The criteria include the populations of cities and counties, which units of government deliver services to residents, how much commerce takes place in a city during the day versus at night, and the point of sale of a particular good or service that is being taxed.

Some businesses have problems identifying where they’re delivering goods or where the tax should be charged, said Jonathan Ussery, Director of Local Government Services for the Department of Revenue, which manages LOST fund distribution.

Because there is not a formula for distribution of funds that incorporates all of the criteria (a prior formula was ruled unconstitutional by the Georgia Supreme Court), the cities and counties are left to interpret how much weight should be given to each one, Clint Mueller, the director of governmental of affairs for the Association of County Commissioners of Georgia, told State Affairs.

When cities and counties can’t come to an agreement, state law requires them to engage in a non-binding arbitration process, said Patel. But counties have a powerful option to use as leverage in those talks: They can threaten to let the LOST expire and to adopt instead a Homestead Option Sales Tax (HOST), a county sales tax used to reduce residential property taxes and to pay for infrastructure projects. HOST tax collections don’t have to be shared with municipalities.

“So one party has that as a hammer, and the other party has nothing to fall back on,” said Patel.

GMA members, including leaders of cities and towns across Georgia, are looking for legal changes to the way LOST negotiations are conducted in the future “that could help reduce tensions and animosity, so there’s less fighting,” he said.

Among them are Julie Smith, mayor of Tifton; Tim Young, city manager of Hapeville; and Marcia Hampton, city manager of Douglasville, who each described to the committee their LOST negotiation experiences last year, during which they said they were hemmed in by an unfair process and the will of their county’s leaders.

Smith said she walked into a negotiation with Tift County commissioners last summer armed with data demonstrating population growth and economic expansion in Tifton since the last LOST was set in 2012, which she said should justify an increase in the city’s share of the sales tax proceeds, to 45% from 30%.

County leaders weren’t interested, she said, and handed her a letter saying ‘If you don’t agree, we’re going to let LOST lapse and impose a HOST.’ After two days of mediation with no progress, she said, “We caved. I couldn’t take it anymore.”

Too much was at stake for Tifton residents if the LOST expired, said Smith — $4 million, a quarter of Tifton’s $16 million general budget. “If I didn’t have that in LOST, we’d have to drop services or cover it through property tax, which is a burden on the citizens,” Smith said. So Tifton agreed to keep the same share of LOST for the next 10 years, she said.

Hapeville’s Young said that on the first day of negotiations last July, just under $4 billion in LOST proceeds through 2032 to be divided between Fulton County and 15 municipalities in Fulton was on the table. Fulton County commissioners proposed reducing the municipalities’ share of collections from 95%, as previously negotiated, to 65%, with 35% now going to the county. If city officials didn’t agree, Young said, “they threatened to go with HOST.”

That would mean a loss of $2.3 million for Hapeville, he said. “That’s half of my police force, one of my two fire stations that I can’t fund. It would be a major hole in my budget.”

Young said the renegotiation process was “traumatic” and “contentious. … I expect contention over $4 billion, but I don’t expect a zero sum game, a no-win scenario.”

Douglasville City Manager Hampton said her team faced the same bind in negotiating with Douglas County, and ultimately “acquiesced” to a 3% drop in LOST proceeds last year, bringing the city’s share to 25%. That will mean raising property taxes by as much as 40% for Douglasville residents to cover the gap, she said.

“This has got to be fixed,” Smith told legislators and other members of the study committee. “Please do what you can to help us.”

Why It Matters

“The majority of cities, and I would imagine the majority of counties, heavily rely on this sales tax to not increase their property taxes and so they can pay for services,” said Patel.

GMA research shows that LOST revenues make up about 25% of most Georgia city budgets, on average, while they supply as much as 70% of the revenue for smaller municipalities in the state.

The bickering among local government leaders over sales taxes creates tension that carries on into other shared aspects of government between cities and counties, Patel said. It can also create a sense of distrust of government among citizens, especially when there is poor public transparency over the negotiating process, which he said is often the case.

“There’s such bad blood and bad tension between the city and county officials, due to what we perceive as mismanagement of county funds,” said Hampton. “We’re still playing triage and will be over the next 10 years.” She called for legislators to create a more level playing field and to consider making binding arbitration a part of the LOST process, “with punitive measures for local governments that don’t play fairly.”

Mueller of the ACCG agreed that negotiations “have been contentious and damaged city and county relations. …We are working with GMA to see if we can reach a compromise on a joint solution. The only real choice is to make the current negotiation process better or come up with another [distribution] formula. GMA and ACCG are working toward a compromise that would make the negotiation process better because any formula would pick ‘winners and losers.’”

What’s Next

Sen. Derek Mallow, D-Savannah, who chairs the Local Option Sales Tax Study committee, said upcoming committee meetings to be held in Griffin, Savannah and Atlanta over the next few months will include presentations by county leaders, including members of the ACCG.

From what he’s heard so far, Mallow said, “We need to have a better way to referee counties and cities in negotiation and ensure that not one body of government should have more power or leverage over the other. At the end of the day, we have to benefit the citizens of each of the counties and cities with a LOST.”

Mallow said he hopes the committee will “establish better guardrails and find the right metrics we should use to determine the percentages of who gets what.” He noted the Legislature has not significantly reviewed laws governing local option sales taxes since 1997.

“As we’ve seen, technologies change and needs change, in terms of the services cities and counties are providing, and what’s needed to keep communities safe,” he said. “You’ve got big economic development projects that are increasing infrastructure needs all over the state.”

Mallow said he’ll push to make sure that future LOST negotiations are required to include public hearings and public comment, “so that John Q. Public has a say in how all this money is spent.”

The report of the study committee is due to the governor, lieutenant governor and legislative leaders by December 1.

Have comments or tips on tax issues? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

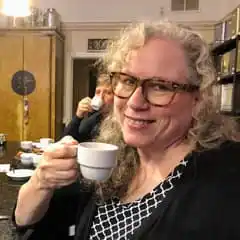

Header photo: City of Douglasville City Manager Marcia Hampton told members of the Senate Local Optional Sales Tax (LOST) Study Committee about her difficult negotiations with Douglas County officials over their LOST agreement, on August 14, 2023 at the Capitol. (Credit: Jill Jordan Sieder)

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …