Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoThousands of third graders move on without knowing how to read. Should they be held back?

Indiana Secretary of Education Katie Jenner speaks during a Dec. 5, 2023, State Board of Education meeting. (Credit: Jarred Meeks)

The gist

Thousands of third graders fail the state’s reading test every year — signaling they can’t read at grade level, but almost all of them still advance to the fourth grade.

Republican legislative leaders, as well as the state’s top K-12 education official, want to tighten rules requiring more students who can’t read to repeat third grade in hopes that they can increase reading proficiency levels in Indiana.

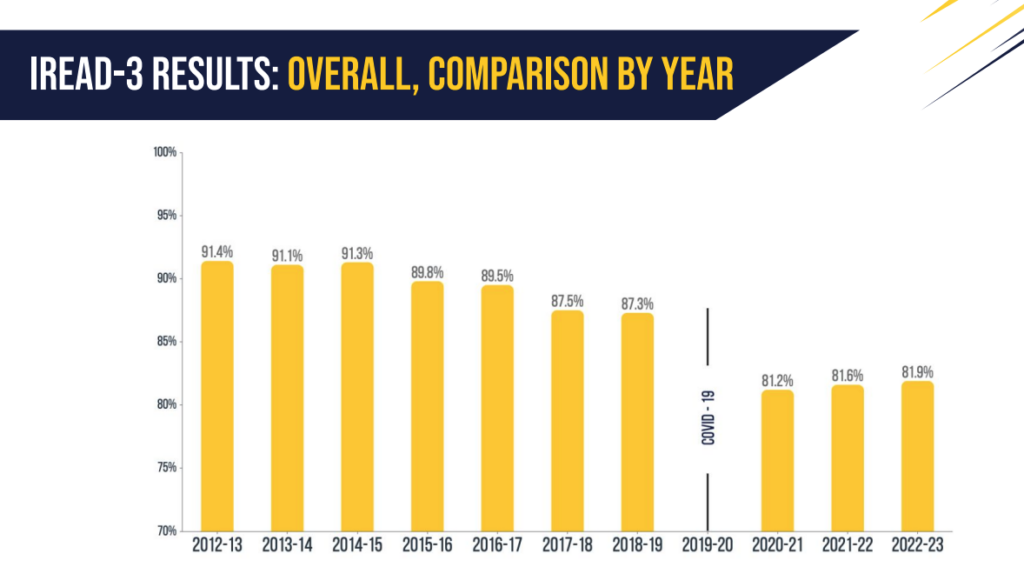

In 2023, nearly one in five third graders failed the IREAD-3 test. That’s more than two and a half times the number of students who failed the test a decade ago when the state had strict retention policies in place.

“When you pass that kid on and they aren’t prepared to succeed, you aren’t doing that kid a favor,” House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, said on Organization Day, the ceremonial start to the legislative session.

But, if history is any indication, requiring more students to repeat a grade would be a controversial decision. Holding back students used to be the de facto policy in Indiana.

Democrats and some educational leaders are encouraging caution before reverting to that policy.

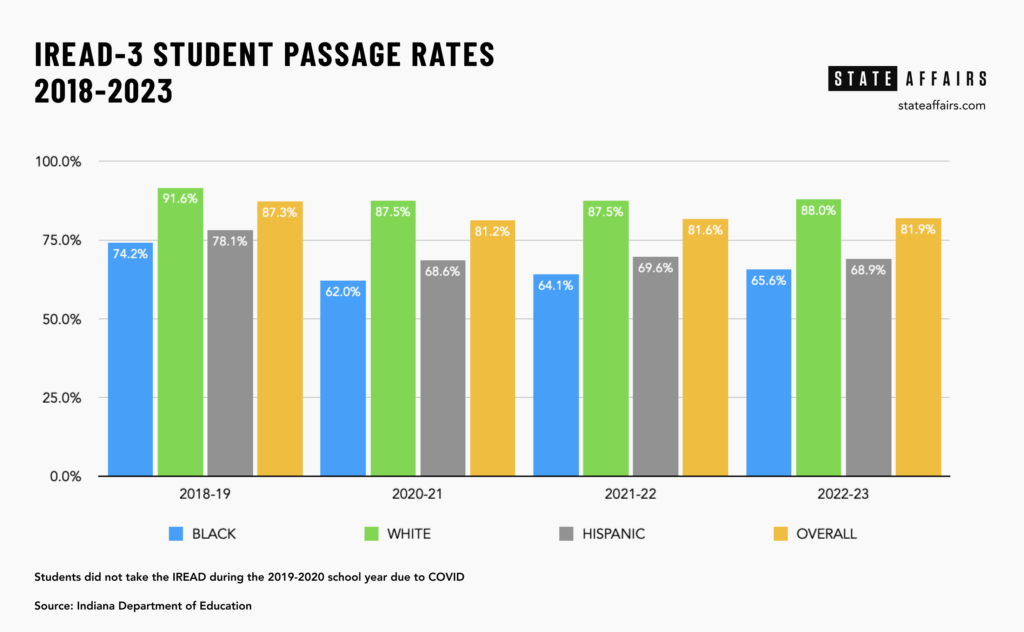

Even proponents of retention admit it is a “disruptive” intervention, while critics worry about the long term social implications of holding back students. It also could cost the state more money to pay for an additional year of schooling. Plus, Black and Hispanic students fail the IREAD at much higher rates, which means those students are the ones who would be retained more often.

“We really have to think long and hard about unintended consequences,” said Sen. Andrea Hunley, an Indianapolis Democrat who has 20 years of experience in public education.

When do schools have to retain students now?

The Indiana General Assembly passed a law in 2010 stating that retention should be used as a “last resort” when a student fails the IREAD test. Since then, additional guidance for schools on what that means has come from the state board that oversees K-12 education.

Since 2017 the State Board of Education has recommended schools “assess the student’s overall academic performance in all subject areas” when deciding whether to require a student to repeat third grade. Those who do move on to fourth grade are still required to receive third grade reading instruction.

English language learners, students in special education and those who had been retained twice also automatically qualify for “good cause exemptions.”

That guidance largely means schools have the flexibility to pass whomever they want to. And as a result, most schools chose to retain fewer students.

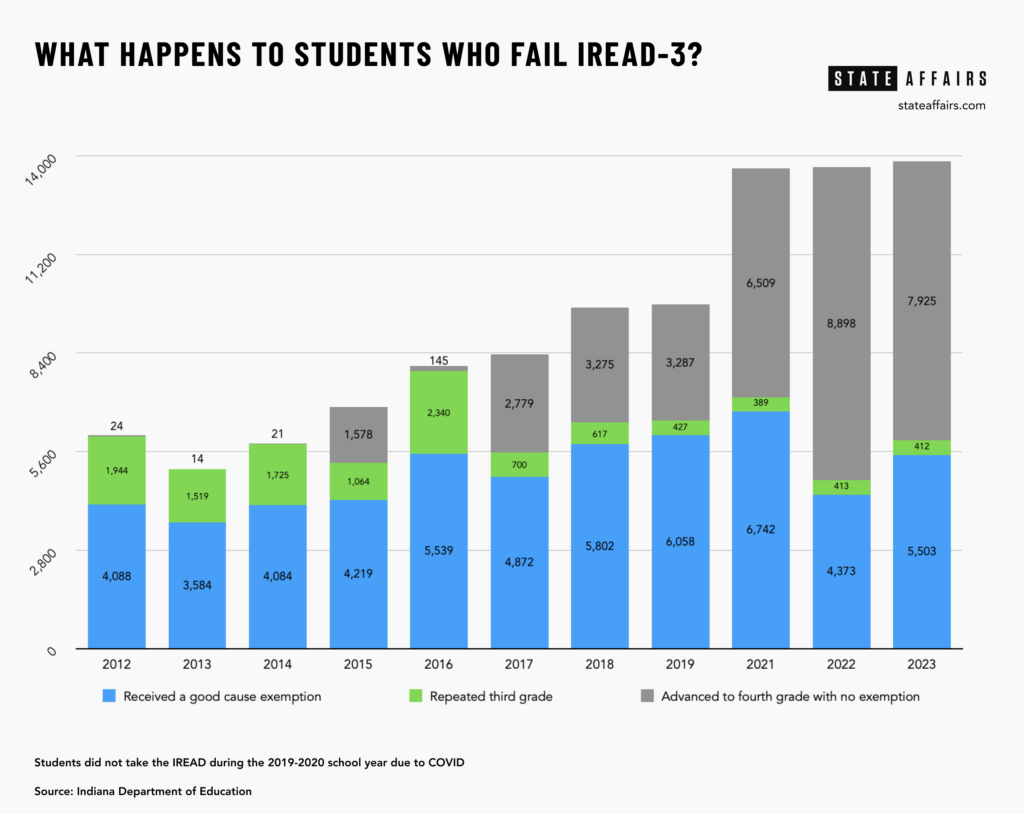

Of the nearly 14,000 students who failed the IREAD test in 2023, only roughly 400 students had to retake third grade. That means 97% of students who couldn’t read at a third grade level moved onto the fourth grade.

A decade ago when Republican state Superintendent Tony Bennett was in power, the state’s policies surrounding retention were much more stringent.

In 2013, for example, only 14 students who failed to qualify for a “good cause exemption” advanced to the fourth grade, while 1,500 students had to repeat third grade.

The policy was controversial back then, too. When Democrat Glenda Ritz became the superintendent of public instruction in 2013, she made changing the retention policy a priority. The policy, though, wouldn’t change until after her tenure.

Since then, IREAD scores have only dropped. During the 2012-2013 school year, 91.4% of students passed the IREAD, almost 10 percentage points more than in 2023.

That’s on trend with statistics across the country: Between 2019 and 2022, the percent of fourth graders who scored below proficient on reading increased in 42 states.

Today, Indiana is in the middle of the pack when it comes to fourth grade reading scores, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which tracks fourth grader tests, not IREAD data specifically.

If a student passes IREAD by third grade, they are roughly 35% more likely to graduate high school, according to the Indiana Department of Education.

“There’s no doubt this is a tough topic. There’s no question,” said Indiana Secretary of Education Katie Jenner. “But we know from our data what happens when children can’t read by the end of third grade and they move forward. And so, that’s broken right now.”

What do studies show about the impact of retainment?

One reason retention is such a controversial concept is because studies on the impact of retention show mixed results, especially depending on at which grade level a student is retained.

Typically, though, students who are held back early in elementary school perform better than their peers who scored low but weren’t held back, at least in the immediate future, said Cory Koedel, an economics professor at the University of Missouri who has studied the issue.

“It’s quite clear,” Koedel said. “It seems that these early grade retention policies have positive effects on kids’ achievement. The larger literature is mixed, but it turns out a lot of the negative effects of retention happens when retention is in later grades.”

He specifically knows the Indiana data well, having studied the impact of Indiana’s 2012-2017 retention policy on academic achievement with NaYoung Hwang, a professor at the University of New Hampshire.

Their study found that those students who didn’t pass the IREAD and repeated third grade performed better in math and English language achievement in fourth grade than their peers with similar IREAD scores.

The study, though, did not follow the students into high school, so the long-term impact on holding young students back is less clear.

Other studies on similar policies in Florida, Mississippi and Chicago came to similar conclusions.

Koedel’s study didn’t directly address how students were impacted when Indiana changed its retention policy. But he does have a theory based on the data he did study.

“It’s not a very big leap to conclude that there were these positive causal effects of retention, Koedel said. “And then they started retaining less students, and so those effects were lost.”

As of 2020, 17 states had mandatory retention laws.

Other potential negative outcomes of retainment

Data on non-academic outcomes is less clear. The Indiana study found no statistical evidence that holding back students adversely impacted their attendance or led to more disciplinary problems. But, a separate study on Florida’s policy found disciplinary issues increased among third graders that had to repeat the grade.

“It’s still very disruptive,” Koedel said. “No matter what, this is not a small touch intervention.”

Both Huston and Senate President Pro Tem Rodric Bray also acknowledged some parents may be unhappy to see their children held back.

“Will it make some parents mad?” Senate President Pro Tem Rodric Bray asked on Organization Day. “Yeah, I suppose so, but they need to be invested in their child’s education and success as well.”

There’s also potential budgetary concerns for schools and the state, because holding a child back means paying for another year of school. Huston said the state will figure out the budget needs.

Ongoing efforts to fix reading proficiency

Brandon Brown, CEO of The Mind Trust, an Indianapolis-based education nonprofit argued retention works, but it can’t be the only tool in the toolbox.

“When you pair third grade retention with a variety of other strategies, it does tend to lift achievement,” Brown said. “So I think it’s important to talk about this not as retaining third graders in isolation but really a comprehensive approach to improving literacy.”

The state already is pursuing a variety of tactics to increase reading proficiency in Indiana.

In August 2022, Lilly Endowment and the Indiana Department of Education announced a $111 million combined investment to support early literacy development. The funds created a literary center focused on the science of reading strategies, supported the deployment of instructional coaches to schools and gave students targeted help, according to the department.

During the 2023 legislative session, state lawmakers passed legislation advocating for what’s called “the science of reading,” a catchall term for research that considers phonics, phonemic awareness, and other science-based teaching methods essential to helping children learn to read.

The state also earmarked $100 million for academic improvement initiatives over the next two years, nearly half of which will support the department’s science of reading initiatives.

Hunley argued that lawmakers should wait to make major changes to the state’s retention laws until they can see how the recent law change will impact reading rates in Indiana.

“We have to give them time to work before we start, say, failing all children or retaining a whole class of children,” Hunley said. “I’d really implore us to allow our legislation time to work.”

During the 2024 legislative session, the Indiana School Boards Association plans to advocate for additional reading initiatives beyond just retaining students.

It favors mandatory IREAD-3 assessments for all second grade students, said Terry Spradlin, the association’s executive director. Currently, Indiana schools may opt to administer the assessment a year early to gauge their students’ progress.

In addition, the association contends second and third grade students who can’t read at their grade level should be compelled to take a mandatory summer school program focused on reading and literacy, Spradlin said, adding that “time on task” is an important aspect of helping students learn to read.

What’s next?

Lawmakers reconvene for the 2024 legislative session on Jan. 8. Legislative leaders will likely roll out their exact recommendations for how to tighten retention rules that week.

Likewise, Jenner and Gov. Eric Holcomb aren’t yet sharing details on what they’d like to see regarding this policy. After a Tuesday State Board of Education meeting, Jenner told reporters that Holcomb’s administration will reveal more about its third grade reading proposal in January.

Jenner said she wants to see legislation move on the topic, but she does want to allow students to advance to fourth grade who do rightfully qualify for a “good cause exemption.”

“But we also have way too many moving forward right now,” she said.

Indiana State Teachers Association President Keith Gambill indicated during a press conference last month that the state’s largest union would wait to share its thoughts on retention proposals until it sees the specifics of such legislation.

Contact Kaitlin Lange on X @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Contact Jarred Meeks on X @jarredsmeeks or email him at [email protected].

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …