Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo‘This is wrong’: How transcript holds block Hoosiers from completing their schooling

Colleges across Indiana can withhold transcripts from former students who owe money in an attempt to incentivize them to pay up. (Credit: Brittany Phan)

The Gist

Colleges across Indiana can withhold transcripts from former students who owe money in an attempt to incentivize them to pay up. The issue, though, is that without a transcript, students oftentimes can’t further — or complete — their education or boost their incomes in order to make enough money to pay back those debts.

Freshman Sen. Spencer Deery, a West Lafayette Republican and former Purdue University administrator, said withholding transcripts creates a “trap” for Hoosiers. He is carrying a bill this legislative session to limit the practice, as long as students are working to pay down their debt.

No college has openly opposed the bill, but some have privately shared concerns.

What’s happening

More than 100,000 Hoosiers owe an average of $2,800 to higher education institutions, according to a 2021 estimate from Ithaca S+R. A majority of universities across the country withhold transcripts in an effort to get those dollars back.

But having no record of college credits can impede someone’s ability to apply for jobs, pursue internships or further their education later on. Those with a college degree make roughly 1.5 times more than those with only some college credit, 2021 numbers from the Bureau of Labor show.

Experts say oftentimes the issue stems from when a student who receives Pell Grants and other financial aid leaves a university in the middle of the semester. When that happens, the university has to return the financial aid to the federal government, leaving the student on the hook for the money.

If that student tries to complete their degree years later, they often can’t obtain their transcript until they pay off the debt. And student loans won’t cover past debt.

Those who drop out at the end of a semester can be burned too. Rep. Ragen Hatcher, D-Gary, knows firsthand. Her son declined to take out student loans at the beginning of the year, thinking his job would cover his educational costs. They didn’t.

He planned to transfer to Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis from another college at the end of a semester, but couldn’t access his transcript due to a $16,000 outstanding balance.

Hatcher dipped into savings and retirement dollars to pay off the debt. Her son was a minor when he started college, which helped him avoid a $4,000 collection fee. The price tag, though, was still a burden.

“For anybody to come up with a lump sum in the thousands of dollars,” Hatcher said, “is difficult no matter if you’re a state representative or a teacher or a doctor or a factory worker.”

Mary Jane Michalak, vice president of legal and public affairs at Ivy Tech Community College, described a similar story. She dropped out of college after her first semester due to family issues 20 years ago. When she tried to return to school years later, she discovered she had debt and was forced to take out a personal loan to pay it off before she could obtain her transcript.

“It was literally preventing me from going back to college,” Michalak said, “and furthering my life.”

The concept of “stranded credits” is a nationwide concern. So far at least six states have banned the practice.

Why it matters to all Hoosiers

Indiana falls short when it comes to college attainment, which those in the business community say hurts Indiana’s ability to attract high-paying employers and jobs. A little over a quarter of the state’s adults 25 years and older have a college degree, 43rd in the country.

“We’re a competitive business state in every metric except for our education,” Deery said. “We need to start figuring out how do we change that, and I think this was a big piece of the puzzle that’s missing from the conversation.”

Multiple companies that have passed up Indiana in favor of other states have referenced the winning state’s labor pool as one reason they made their decision. For example, Intel, a Silicon Valley semiconductor maker, chose the Columbus, Ohio, area to construct two new chip factories in part due to its “strong talent pipeline sustained by world-class educational institutions”.

In Indiana alone, more than 800,000 Hoosiers 25 years of age and older have some college credits but no degree, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

It’s unclear how many of them would return to school if they were not required to pay off school debts to acquire past transcripts. However, lawmakers and supporters believe every bit helps ensure Indiana’s talent pool.

“[Some people] are stuck in sort of a transcript limbo, lacking a record of the college credits they’ve earned, saddled with debt and stymied from completing the remaining credits to earn their degree,” said Jason Bearce, vice president for education and workforce development at the Indiana Chamber of Commerce, “which will of course increase the prospect of paying off that debt.”

What lawmakers are proposing

Senate Bill 404 would prohibit state or private for-profit colleges from withholding transcripts from former and current students that owe money to an institution, as long as they are making some payments.

“I wanted to give them a little nudge to say this is wrong,” Deery told State Affairs.

If a student owes less than $1,000 and paid at least $100 in the past year toward the debt, the university couldn’t withhold a transcript. Likewise, students who owe more than $1,000 and paid the lesser of 10% of the total debt or $300 in the past year, the university couldn’t withhold their transcript.

The bill no longer applies to nonprofit post-secondary institutions, because those colleges don’t have the ability to intercept tax rebate money, Deery said.

The legislation could still be amended as it works its way through the Senate.

Will this hurt universities?

No organization spoke against the bill in committee, but Deery said he has heard concerns about the bill’s impact from colleges.

A spokesperson from Indiana University told State Affairs the university is “watching” the bill, but provided no comment beyond that. Likewise, a spokesperson for Purdue University said the college “will continue to work with the bill’s authors,” adding that the college works with students to release transcripts when it could lead to jobs that help pay off debt.

But public colleges searching for a blueprint to ensure they can still collect money from former students can look to Ivy Tech, which operates 43 locations throughout Indiana.

Ivy Tech chose to release transcripts for the almost 83,000 students who owed the system money in late 2021. More than 3,000 people have reached out to obtain their transcripts since the policy change.

Ivy Tech still can collect money from former students by intercepting their tax returns if they aren’t participating in a payment plan, allowing the university to collect about $4 million per year, Michalak said.

A spokesperson for Ball State University said the university also stopped withholding transcripts “a few weeks ago,” after the bill had already been introduced and following months of internal discussion.

Deery said he’s trying to find a balance with his bill and understands that colleges need to incentivize students to pay down debt somehow.

“But,” Deery said, “what I do have a problem with is if there is a debt getting in the way of somebody’s educational journey.”

The bill won’t eradicate the problem for all former students who owe money, since private universities are excluded from the bill.

What’s next?

SB 404 passed out of the Senate by a 47-2 vote last month, but it’ll need to also pass the House before it can become law.

The House Education committee is scheduled to hear the bill on Wednesday.

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: Illustration by Brittany Phan/State Affairs

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

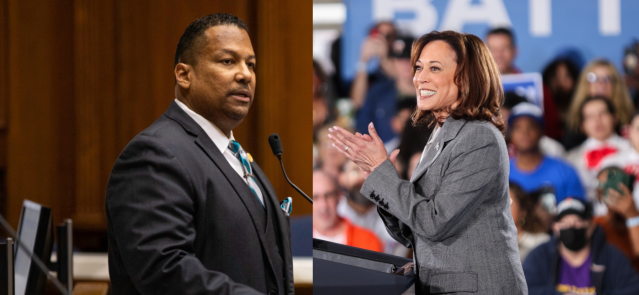

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …