Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoFamilies disappointed by legislation to address attendant care services

Jennifer and Jackson Dewitt pause for a photo. (Credit: Jennifer Dewitt)

Jennifer Dewitt spent Friday, her first free night in months, at the Statehouse. She hopped on and off Zoom meetings to keep other parents informed and tried to speak with legislators when she could. But her night, like many other parents’, ended in disappointment.

Typically, Dewitt spends her days and nights caring for her 16-year-old twin sons, Jackson and Matthew, at her Noblesville home. They were born 13 weeks premature because of a pregnancy complication, she says, resulting in an array of medical challenges — more than 25 surgeries and 60 in-patient stays between them. Doctors didn’t expect Jackson to live long enough to experience his first birthday. At 5 feet, 6 inches, he is now taller than his mom.

Dewitt provides what’s called attendant care for Jackson through the state’s Aged and Disabled waiver, which allows a provider agency to reimburse her at an hourly rate for her services, often for 80-85 hours a week. (Matthew is cared for under a different waiver.)

The pay, close to $15 an hour, according to Dewitt, is enough to help her family, which includes her husband, their children, her father and her mother in a nearby nursing home, get by.

But on Jan. 17, the state announced plans to no longer allow biological parents and guardians of minors and spouses — who the state dubs “legally responsible individuals” — to provide attendant care starting July 1. The agency’s plan is to allow them to transition to the state’s Structured Family Caregiving program, which often pays less under a capped per diem structure. Caregivers would get at most a portion of $133.44 a day under the structure; provider agencies would keep the rest. Otherwise, the families will have to find another attendant caregiver.

The announcement gutted Dewitt, whose family closed on a new house only two weeks before the announcement. They never would have if they had known, she said.

The proposed transition is part of the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration’s reaction to a $984.3 million Medicaid forecasting error it made in 2023. Families providing attendant care to minors, the administration says, account for a disproportionate share of the unexpected costs.

Specifically, increased utilization — many attendant caregivers are reimbursed for more than 60 hours a week — has driven higher expenditures. According to the administration’s data, the state’s attendant care costs climbed to about $120 million in December 2023 from about $30 million as recently as April 2022.

To corral the expenditures, the administration, on Jan. 17, also stopped allowing new parents, guardians and spouses to enroll in the Aged and Disabled waiver program, paused a 2% rate indexing across Medicaid services broadly and planned to limit the number of service plans with automatic approval. By implementing the changes, among others, the administration estimates it can save the state as much as $300 million a year.

Senate President Pro Tem Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, previously said that the state now “has to be fiscally responsible” and that the administration’s plan ensures the waiver program “functions in a way that it needs to function but [so that] it’s not as exorbitantly expensive as it has been.”

Parents, guardians and spouses were first allowed to provide attendant care in 2017, a policy change that wasn’t in compliance with the state’s waiver with the federal government, said Kim Dodson, CEO of the Arc of Indiana, a nonprofit that helps people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. However, a spokesperson for the administration said, “FSSA is not aware of legally responsible individuals providing attendant care services prior to 2020.”

The program became more popular during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when parents sought an alternative to bringing another person into their home, and it has continued to take off. Legislators have argued that the transition is needed to bring the state back into compliance with its Medicaid waiver. Not doing so, they say, would risk federal funding.

Dewitt and other parents realize that the program is growing at an unsustainable rate and that cost-saving measures are needed. But they assert that the administration erred by not establishing guardrails for the program “like many other states do.” If it had, “maybe that would have prevented all of this from happening in the first place,” Dewitt said. “But there was no real guidance given to any of the care managers, and everything was approved by FSSA.”

During the legislative session, Dewitt was one of several parents who rallied at the Statehouse nearly every week to raise awareness of their families’ plight. Often dozens of parents attended the rallies with their children. Visitors saw a line of wheelchairs greeting them. The parents’ hope was to persuade lawmakers to intervene in the administration’s plan. Dewitt even joined House Democrats for a news conference in which the lawmakers called on their Republican colleagues to act.

At first, their efforts seemed promising. Behind a wave of bipartisan support, House lawmakers heavily amended Senate Bill 256 in an attempt to address the issue. But legislators added only a few of the provisions to another bill, House Bill 1120, after the Senate’s legal team said most of the add-ons to Senate Bill 256 were not germane to the measure.

In the final version of House Bill 1120, which awaits a decision from Gov. Eric Holcomb, lawmakers included language that would require the secretary of family and social services to present a policy to the State Budget Committee by the end of the year. The policy would set a minimum percentage of reimbursement for personal care services — including structured family caregiving and attendant care — that must go to the person providing the care. Previously, representatives had wanted at least 80% to go to the caregiver but quickly found that the proposed split wouldn’t work.

The bill’s final version would also require the secretary to “prepare and present a plan to monitor expenses” of the state’s Medicaid program. The plan would feature proposed transparency improvements, an explanation of how the forecasting error occurred and information on how the administration plans to transition caregivers from attendant care to structured family caregiving.

On Friday, Bray told reporters that the state had found “some abuses in the [attendant care] program.” The bill would “make sure this program remains viable,” he said.

Asked by State Affairs about the Family and Social Services Administration’s confidence in producing the policy and reports described in the bill, a spokesperson for the administration said, “FSSA will comply with the law.”

While grateful for some legislative intervention, Dewitt said the bill “really fell short of a true fix for our families, and it has left us in the same boat we were in on Jan. 17, when this was all dropped in our lap[s] by FSSA.” She argued that the bill would be “too little, too late” for many of the affected families.

Particularly, affected families wanted lawmakers to include an amendment authored by Rep. Ed Clere, R-New Albany. Clere’s proposal would have defined “extraordinary care” and, through a waiver amendment, allowed families to continue providing attendant care to minors whose needs met the definition. It also would have created a higher tier of reimbursement for caregivers providing extraordinary care under the Structured Family Care program. The proposal, however, did not survive conference committee negotiations with the Senate after receiving bipartisan support in the House.

“I’m disappointed we weren’t able to get more, and ultimately we came up short,” Clere told State Affairs. “I’m glad we managed to get something in the bill, regarding reporting on the transition, but I would have liked to have seen a lot more detail and a lot more urgency.”

Dodson echoed Clere’s sentiments: “I think it’s hard not to be disappointed. I think we appreciate the two things that did happen. And those are very important. But I think what we’re most concerned about and most disappointed in is for those families who truly needed something else to happen … that’s where things just fell short.”

While Dewitt roamed the hallway outside the House chamber, House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, made comments that upset some families Friday night. “Let’s wait and see what the real outcome of the change in the structure is,” Huston told reporters Friday after House Bill 1120 passed out of his chamber. “I think there’s a lot of discussions being had without comprehensively, fully seeing … what [the] implementation looks like.”

Tendra Duff, another parent staring down the transition, wonders why legislators would be content to wait. “Why are we waiting? Why are we waiting to see if [it’s] life or death or if disparity happens to our families?” she asked.

Renee Case, another parent with a medically complex child, believes some of the affected families will turn to other Medicaid programs, such as food stamps and housing assistance.

“We don’t go on vacations or buy top-of-the-line stuff,” Case said. “We are just trying to keep our kids alive, and they’re taking all of the resources away from us.”

Legislators declared Sine Die shortly after they passed House Bill 1120. They applauded for the ceremonial end to the legislative session. Many lingered for photos and hugs.

After waiting to thank the legislators who were sympathetic to her cause, Dewitt went home and ate a “big ol’” piece of cake.

Then she resumed her daily routine.

Dewitt shares a bedroom with Jackson; their beds are diagonal to each other. His has wooden sides with Plexiglas windows, reminiscent of a hospital bed. Jackson, who’s “functionally nonverbal,” has dimples “a mile wide” and loves hugs. Dewitt says, cognitively, his brain functions close to that of a 6- to 12-month-old.

The challenges of caring for Jackson and Matthew led Dewitt and her husband to divorce (they later remarried). She lost her home, her car. Before they bought their new place, Dewitt slept on the floor of their previous home, next to Jackson, getting, she said, only a few hours of sleep at a time.

As she prepared to sleep in her own bed Friday night, she checked to make sure her son’s myriad machines looked right. Everything was charged; everything was plugged in. She lay in bed knowing an alarm would wake her soon. It might be his BiPap machine or oxygen monitor, or she might need to use the suction machine. That night, Jackson nudged his mask off. An alarm sounded and Dewitt rose to fix it.

Monitoring Jackson throughout the night to make sure he lives to see the next day is her job, even if she doesn’t get paid for it.

“I do that,” she said, “because I’m his mom.”

Updated: This story was updated to include a response from FSSA.

Contact Jarred Meeks on X @jarredsmeeks or email him at [email protected].

X @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairspro

Know the most important news affecting Indiana

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

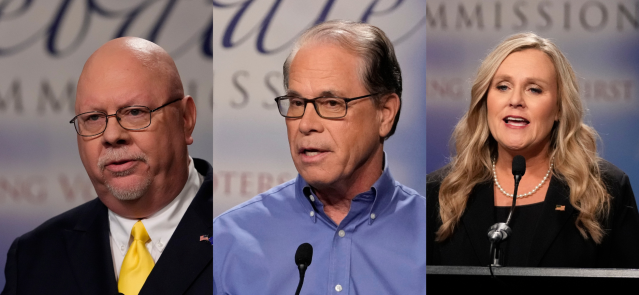

McCormick, Rainwater attack Braun’s ticket in final debate

In the last gubernatorial debate before the November election, Democratic nominee Jennifer McCormick and Libertarian candidate Donald Rainwater ramped up attacks on Mike Braun and his Republican ticket. The three candidates faced off Thursday during a televised showdown organized by the Indiana Debate Commission. McCormick called Braun’s lieutenant governor running mate Micah Beckwith “the definition …

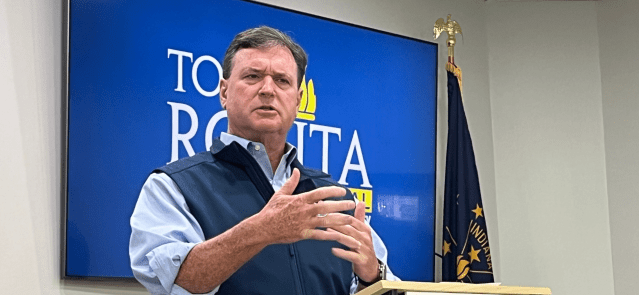

Rokita: Voter citizenship review may trigger prosecutions

Attorney General Todd Rokita said he intends to use the results of a citizenship status review of nearly 600,000 Indiana registered voters for possible criminal prosecutions. Rokita sidestepped taking a position on whether three justices on the Indiana Supreme Court, which sanctioned him last year, should win statewide retention votes while he spoke with reporters …

7 Indiana down-ballot races and questions, explained

Hoosiers will vote to elect a new governor and the next U.S. president on Nov. 5, but important local races and issues will also be determined further down the ballot. Voters will decide on a constitutional amendment, elect or retain judges and choose new leaders for their local school districts. A full list of candidates …

Voter guide: 9 things to know for Election Day

The general election is less than two weeks away. Here are nine things to know as you make a voting plan for Nov. 5. When do polls open and close? Indiana polls open at 6 a.m. and close at 6 p.m. local time. Where do I vote? Indiana’s voter information website shows voters their polling …