Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoIndiana appeals court chief judge on AI, mental health, and the state’s dwindling number of lawyers

Indiana Court of Appeals Chief Judge Robert R. Altice Jr. sits in his office at the Indiana State Capitol. (Credit: Rory Appleton)

Many Hoosiers may be familiar with their local courts or hear about the opinions of the Indiana Supreme Court, but a middle tier in the state’s judiciary system shapes justice through some 2,000 rulings a year.

The 15 judges of the Indiana Court of Appeals dole out opinions on everything from murder and fraud to civil and child welfare cases. Every Hoosier has the right to appeal a conviction or ruling, and the Court of Appeals, the second-highest court in the state, takes up each case sent its way.

Chief Judge Robert R. Altice Jr. has analyzed thousands of cases since being appointed by Gov. Mike Pence in 2015. Prior to that, he spent 15 years as an elected judge in Marion County.

Altice sat down with State Affairs for a discussion on the ins and outs of his court, how changes in technology and mental health care have impacted his work and what he sees as a major problem facing the nation’s judicial system.

This conversation has been edited for clarity, brevity and length.

Q. What sort of cases does the Court of Appeals hear?

A. We hear really everything except death penalty cases. If there’s a death penalty case, it goes straight to the [state] Supreme Court. Otherwise, we get it.

I’ve had to publish an opinion on a traffic court case. About 65% of our cases are criminal. Every, everything under the sun: murders, rapes, robberies, child molestation.

Then there are civil cases. We do medical malpractice suits, traffic accidents, you name it. Complex business litigation? Our court was involved.

Q. How does the appeals process work? There’s not a new trial, right?

A. I’ll give you an example. Let’s say you got a murder case and the defendant gets convicted and gets 65 years, which is the max for a murder conviction. Everybody in the state of Indiana has got an automatic right to appeal. Not everybody takes that right, but most criminal defendants do.

Somebody will write his brief for him. That attorney will find three issues that they think will result in a new trial if we rule in their favor. That’s really what the appellate process is: Are the errors committed at the trial court level significant enough to warrant a new trial?

And then the attorney general in the criminal cases will write a brief in opposition, then the appellant or the defendant can file a reply brief as well.

We sit and read transcripts and their briefs and do our own research and come to a decision as to whether or not there was error at the trial court level that warrants a new trial.

Q. How many of the 2,000 cases your court receives a year, how many are taken up by the Indiana Supreme Court?

A. It is rare. You start with the proposition that trial courts throughout the state are doing about 2+ million cases a year. That’s everything. We do 2,000 opinions a year. I think the Supreme Court writes about 60 opinions a year. That’s what their taking of ours.

But we’re considered an error-correcting court, whereas that’s really not their role. Their role is more jurisprudential. It’s “should we look at changing in this regard or changing precedent.”

It’s really an inverse pyramid, with the trial courts, I always say, doing the heavy lifting.

Our turnaround time is very quick. It’s about three months. Some states require oral arguments in every single case, but we don’t.

If you ask for an oral argument, we will sometimes grant that. We do a lot of oral arguments, but most of our oral arguments are traveling oral arguments. We travel all over the state and do live arguments. And we do those in front of high schools, small colleges, bigger schools.

We answer questions or ask questions like we normally would do, and then once we’re finished, then we have a question and answer session with the students.

Q. One thing we heard about at the State of the Judiciary is there’s an attorney shortage in the state, particularly in rural areas. How has that affected your work?

A. I think we’re seeing more pro se litigants, people representing themselves, and that can be difficult because we hold them to the same standard that we would hold a lawyer to. It can be really difficult for them. So in that regard, it has hurt.

We’ll go to traveling oral arguments in some rural county, and the bar association will host a lunch for us. We’ll go and there’ll be six lawyers in the room and I’ll say to somebody, “So how many people are in the bar?” And they’ll say, “Well, you’re looking at it.”

That access to justice is a really difficult thing that I think the state of Indiana is dealing with now. The Supreme Court has just set up a task force to look into how we can improve that. I believe law schools are looking at incentivizing young kids to go practice in rural areas.

It’s a real issue. I think a lot of it stems from the low bar passage rate of the last 10+ years. It’ll be interesting to see what the task force thinks.

Q. How has technology impacted the court?

A. Technology has been huge. All our work is done online now. The briefs are filed online.

The technology that we have to keep an eye on, and we’re already looking at, is artificial intelligence. What impact is that going to have on the courts, especially our courts?

You can punch a button and write an opinion. It’s probably not going to be very good, but as technology improves, it’s going to be. We’re kind of leery of that.

But at the same time, from a research standpoint, it’s been a very valuable tool. We’ve been using AI in that regard for researching for some time now, with Westlaw and Lexus as they’ve come out with those kinds of tools.

Q. There have been changes in how the world views mental health. How has that impacted the court?

A. I see it primarily in the sentencing arena. Before every defendant is sentenced by a trial court, a pre-sentence investigation is prepared on them. And so that’s where you see a lot of that because it discusses their entire background, and the number of people with mental health issues coming through has really increased greatly.

I think the pandemic had a lot to do with that as well. But again, the mental health issues are very much creeping into the system, and one of the things that we’re constantly working on trying to be aware of and trying to, to the extent we can with alternatives to incarceration, assist people.

Q. Are there any other challenges facing today’s judiciary?

A. I guess not necessarily my court, but courts in general. It appears to me that Congress is broken. They’re not passing laws.

So, what are we doing? We have to rely on the other two branches of government to kind of take up the slack, and that’s why you’re seeing tons of executive orders.

That’s not traditionally their job, and then you’re seeing the courts being called upon to determine whether or not those regulations are enforceable.

I see that as a long-term problem that we’ve got to get corrected.

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

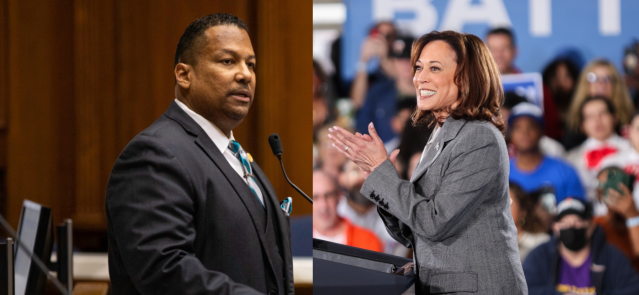

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …