Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo‘1,000-year events’ keep happening. How can North Carolina better prepare?

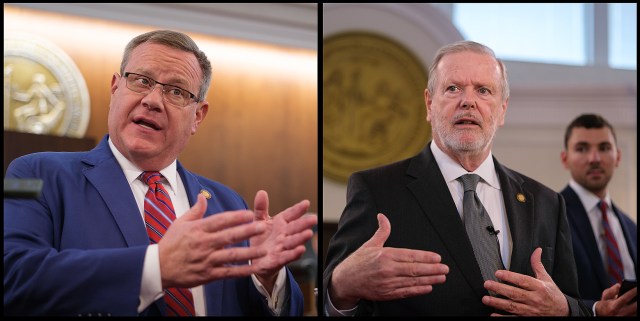

Senate leader Phil Berger is joined by House Speaker Tim Moore and dozens of legislators on Oct. 9, 2024, to release the General Assembly’s first disaster relief proposal for damage caused by Hurricane Helene. (Credit: Clifton Dowell)

- Helene is estimated to have an economic impact of over $50 billion

- North Carolina is experiencing more and more billion-dollar events

- State needs to plan for changes in climate forecasting, experts say

Hurricane Helene is the deadliest storm in North Carolina history.

The overall impact of damage from Helene will likely exceed $53 billion, an initial assessment conducted by the Office of State Budget and Management suggests. The death toll reached over 100 reported deaths in the state on Oct. 30. More than 100,000 homes are estimated to be damaged, with thousands having experienced catastrophic impacts.

As recovery efforts continue and residents try to piece their lives back together in hard-hit Western North Carolina, Helene’s economic and social ramifications on the state will slowly become clearer in the coming months and years.

In the aftermath of Helene, the state’s response has been swift, as officials recognize that much more needs to be accomplished to give Western North Carolinians relief. The General Assembly approved close to a billion dollars in two relief packages in October, and legislators expect Helene will be the dominant topic for state lawmakers in the ensuing years.

“We know there’s going to be more that we have to do in October, more we have to do in November,” Speaker Tim Moore said in the House chamber on Oct. 9. “And frankly, I suspect as we roll into next year, this is going to be something that those of you who are going to be back next year are going to be working on as well for a couple of years to come because the amount of work that is going to be needed is massive. The good thing is no one is sitting around saying,‘What do we do?’ There are plans being developed, there is action being taken, roads are being restored.”

Catastrophic, deadly storms causing billions of dollars in damage have become more frequent in North Carolina. Hurricanes Floyd, Matthew and Florence all struck within the past 25 years. Hurricane Fred in 2021 brought devastation to Haywood County in the same area that is grappling with Helene.

“I remember a couple years back, Rep. [Mark] Pless, Speaker Moore and I were standing on a bridge in Canton [in Haywood County] and we were surveying the devastation,” Rep. Karl E. Gillespie, R-Macon, said on the House floor on Oct. 24, recalling Fred’s aftermath. “We said, ‘Wow, how can this be? And surely this would never happen again.’ Two years later, we eclipsed that, tenfold over.”

Helene is the precedent now

The increasing frequency and intensity of storms is not only shattering expectations but also shattering records — and changing how governmental leaders and communities approach communication on emergency preparedness.

Haywood County in North Carolina has had two proclaimed “1,000-year events” in the past three years.

In 2021, Tropical Storm Fred caused six deaths and massive flooding in the small county. Three years later, Hurricane Helene devastated Haywood County in an identical scenario of heavy precipitation followed by high winds. Helene wasn’t isolated to one county but centralized in the entire region of Western North Carolina, affecting 25 counties. Communities received as much as 20 inches of rain prior to Helene, an exorbitant and unprecedented amount of precipitation.

Fred should have been a wake-up call for North Carolina, according to Rob Young, a geologist at Western Carolina University. The state needs to be smarter about how and where it builds, as well as how communication on emergency preparedness can be conveyed to residents, he said.

“Calling it a thousand-year event doesn’t mean it won’t happen again for another thousand years,” Young said.

Hurricane Matthew was similarly identified as a statewide “wakeup-call” in a presentation by Reide Corbett, dean of Integrated Coastal Programs at East Carolina University, to the Agriculture and Forestry Awareness Study Commission in August.

If Matthew — which caused 31 deaths and over $5 billion in damage in 2016, a level unforeseen in the state — was a wake-up call, what was Helene, which was astronomically deadlier and costlier?

“A really loud alarm,” Corbett said in an interview with State Affairs. “We keep saying unprecedented. These sorts of storms are becoming more and more of a precedent.”

“The idea of calling something a 100-year storm or 500-year storm or 1,000-year storm is based on historic statistics, and it just doesn’t work anymore,” Corbett said in an August presentation. “These storms are changing and what is happening today is not the same that it was 10 years ago. We have to plan for how that’s going to change moving forward.”

In the presentation, Corbett outlined North Carolina’s vulnerability to hurricanes and flooding and the damage and increasing number of billion-dollar natural disasters. Corbett warned that heavy precipitation preceding and accompanying hurricanes will likely increase, which poses a greater risk of freshwater flooding in the state, a scenario that played out with devastation less than a month later.

“This is a tragic storm,” Corbett said, adding it will take months to understand the full scope of Helene’s impact. “But I do think we need to be prepared for more storms like this.”

Corbett noted that during Helene, the small town of Canton in Haywood County flooded in the same manner it had two years earlier.

Building smarter

Are there steps North Carolina can take to mitigate and prepare for these billion-dollar events?

“Absolutely,” Rep. Jimmy Dixon, R-Duplin, chair of the Soil and Forestry Commission Committee, said, citing the state’s $20 million data collection and mapping program. “We’ve never had our circulatory system mapped — by that I mean our rivers, creeks and streams.”

Dixon, a tom turkey farmer, believes the state never fully recovered from Hurricane Hazel in 1954. He compared the waste in the North Carolina waterway system prior to that storm as “cholesterol in our veins and our arteries” that contributed to the widespread devastation.

There have been recent changes in post-disaster recovery in the state. The creation of a local recovery manager position has established a point person who understands the surrounding community. Flood and surge maps have been updated, and the state has undertaken a Flood Resiliency Blueprint. The Streamflow Rehabilitation Assistance Program established in the 2021 budget allocated $38 million toward removing debris from 612 miles of primarily Eastern North Carolina waterways to mitigate flooding.

Several news outlets, including The New York Times, have published articles after the storm claiming North Carolina’s lax building codes are partly to blame for the destruction seen in western North Carolina. With the Republican-dominated Legislature’s override of House Bill 488 last year, the state’s building codes are locked in place until 2031. The building codes North Carolina adopted in 2018 go into effect in 2025.

“I thought that [The New York Times article] was simply wrong … to say that regulatory reform in these cases somehow makes buildings more susceptible to damage,” House Speaker Tim Moore said during a news conference on the relief package.

“That is simply not true,” Moore said, calling the reports false political narratives. Stronger building codes would not have saved many of the Civil War-era buildings destroyed by Helene, he said.

Todd Sims, director of regulatory and industry affairs for the National Electrical Manufacturers Association, disagreed, saying stronger building codes are necessary.

The building code set in place by HB 488 “leads to less resilient, less safe homes, especially in the face of extreme weather events,” Sims said. “Even compared to neighboring states, North Carolina is definitely lagging significantly behind.”

Being smart about how and where we build in the recovery process is necessary, Corbett and Young agreed.

Climate models and forecasting get better with updated data. These storms are tragedies but can be instructive tools for collecting that data. The best flooding model is now available in the state — just look at where Helene caused the most damage, Young said.

“One would hope that in those places where we lost significant infrastructure that we’re going to think really hard about how and where we put stuff back,” Young said. “I’m afraid that one of the things we‘ve learned from Helene in the mountains, even in the areas that we knew were clearly in a flood zone, mapped into a flood zone, is there were still too many people there during the storm. … That should never happen. We weren’t prepared even for what we should have known what was going to happen.”

Put quite simply by Corbett: ”Flood plains flood. That’s why they are called flood plains.”

About 577,000 people — a fifth of the population — living in the 27 counties in North Carolina under a major disaster declaration after Hurricane Helene had high social vulnerability to disasters, with a greater share of older adults, people with disabilities and mobile homes, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Community Resilience Estimates. Counties in the state under a major disaster declaration housed 138,000 mobile homes.

Billion-dollar events are becoming more frequent in North Carolina, and the damage is taking place in expected areas, Young said. Scientists know where the flood plains are and how high the rivers crest during these storms, but residents need a clearer way to understand the potential dangers they face.

“What we are discovering in many, many places is that what we thought we knew about the recurrence intervals of storms is wrong,” Young said. “That big events happen much more frequently and, on top of that, if [the] climate continues to change, if the atmosphere continues to warm, if the Atlantic and the Gulf continue to warm, then these events are going to happen even more frequently than they have in the past.”

Given the increasing frequency of these storms and the projections of what is to come, Helene isn’t anomalous, but may be part of a trend of storms that will wreak havoc and displace many North Carolinians. The “1,000-year event” misnomer isn’t indicative of how these storms affect North Carolina right now, both scientists agreed.

“We know what the flood levels were, we know where the water was, we know where the velocity was,” Young said of Helene. “The trick now is to really use that information to guide future planning and any future development. To me, that’s the message and that’s what we should do.”

For questions or comments, or to pass along story ideas, please write to Matthew Sasser at [email protected] or contact the NC Insider at [email protected] or @StateAffairsNC

Know the most important news affecting North-carolina

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

Josh Stein elected governor, defeating Mark Robinson in heated, historic race

RALEIGH — Voters in North Carolina selected Democrat Josh Stein to be the state’s next governor on Tuesday, bringing to a close a campaign that drew the attention of the country, often for the wrong reasons. With 2,288 of 2,658 precincts reporting, Stein had garnered 55% of the vote; his Republican opponent, Lt. Gov. Mark …

Election Day 2024: State Affairs brings you the fair, transparent, nonpartisan coverage you deserve

Election Day is here and State Affairs stands ready to bring you the kind of election coverage you deserve — fair, transparent and rooted in a commitment to nonpartisanship. Across the states, voters are casting their ballots, deciding on leaders and policies that will shape our communities and futures. And as the results come in, …

Governor, Dem candidates cheer Stein at Chapel Hill pep rally

Carolina students interested in Democratic Party politics were in luck Monday as Gov. Roy Cooper and several statewide candidates energized a get-out-the-vote pep rally for Josh Stein on campus. “Just a 1% or 2% increase in young people turnout will turn the tide of this election, so it is in your hands,” the governor said. …

Defamation lawsuit: Mark Robinson calls news reports ‘political interference’

Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson filed a $50 million defamation lawsuit Tuesday against CNN and a man who claims Robinson frequented a porn shop two decades ago, saying both played a role in efforts to intentionally damage his campaign for governor. “We are glad to take these first steps to fight back against what we consider …