Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoGeorgia’s burdensome licensing proves daunting for professionals seeking to practice. Here’s what senators want to do about it.

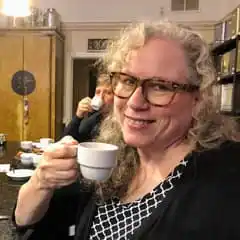

Farangais Saidi (right) and her husband Sayed Sajjad (center left) at their home in Snellville with their two sons, Harakhsh Sajjad (left) and Hoshang Sajjad (center right). Saidi, an OB/GYN doctor trained in Afghanistan, hopes to practice medicine in Georgia. Sajjad, an orthopedist, said the family can only afford for one of them to pursue medical licensing in Georgia at present. Both doctors are currently working as pharmacy technicians.(Credit: Jill Jordan Sieder)

Farangais Saidi is an obstetrician and gynecologist whose medical career has been derailed twice. First, by the Taliban in Afghanistan. Then by Georgia law.

When she was a year into her medical training, the Taliban took control of Afghanistan and forced Afghani women to stop pursuing professional careers. Saidi said she spent three years largely hiding in her home, afraid to go outside, until the Taliban was ousted by U.S. forces in 2001.

Then Saidi was able to complete her medical training at a maternity hospital in Kabul. In 2015, she came to the U.S. with a group of foreign doctors touring American hospitals to learn about best practices. During that time the Taliban came back into power, and she was advised it was not safe for her to return home.

Separated from her husband and two young sons, Saidi moved to Georgia and worked as a medical scribe for a free clinic in Clarkston serving other refugees. Two years later, her family was granted approval to immigrate from Afghanistan, and they moved to Snellville.

Saidi, 42, and her husband, Sayed Sajjad, 38, an orthopedic doctor who also trained in Kabul, now work as pharmacy techs at an Emory University Hospital clinic in Decatur. Both would like to resume practicing as physicians. But they, like many other foreign-trained physicians, are finding the medical licensing requirements in Georgia daunting.

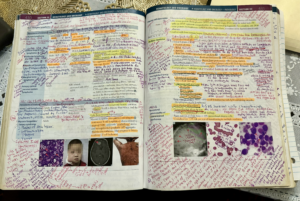

Despite their years of medical training and experience, Georgia’s Composite Medical Board doesn’t credit much of it towards a state medical license. Saidi is spending several hours a day studying for the first of three rounds of the national medical exam. Then she’ll have to repeat her four-year OB/GYN residency, if she can find a placement at a hospital in Georgia or elsewhere in the U.S., where residency spots are hard to come by and highly competitive.

So far she’s spent $10,000 on books and study materials, and anticipates the cost of applying for residency at over a hundred hospitals will total several thousand dollars. Meanwhile, she’s making $25 an hour at the pharmacy, mixing up intravenous medications.

“I love this country, but I feel miserable not being able to practice medicine here,” said Saidi. That feeling was only heightened during the pandemic. “They needed doctors so badly, and I was sitting at home, not allowed to do it. I could’ve helped save lives,” she said.

Sajjad said the family can only afford for one of them to pursue medical licensing in Georgia at present. “The system is so hard to get into, and there is no guarantee to get a residency after putting in several more years of studying,” he said. “If she can get in, I will follow her.”

The challenges facing foreign-trained doctors trying to obtain licenses in Georgia are among the barriers to workforce participation taken up by a Senate study committee on occupational licensing over the past several months. The committee, which issued its final report last week, heard from people representing a variety of regulated industries and professions.

Among those who presented was Darlene Lynch, chair of the Business & Immigration for Georgia Partnership.

Though 1 in 5 licensed doctors in Georgia is foreign-born, Lynch said, many more immigrant doctors and health care professionals live in Georgia but cannot practice here. She urged the committee to adopt the licensing practices of seven other states which have developed expedited pathways for skilled immigrant doctors to become licensed.

Among them is Tennessee, which passed a new law last May allowing international doctors to work as “assistant physicians” under the supervision of a health care provider that trains residents. After two years of successful and safe practice, these doctors are granted a full medical license, and those who already completed residencies in their home countries don’t have to repeat them.

Such legal reform could have a significant impact on the health care workforce in Georgia, where most of the state is medically underserved: 65 of Georgia’s 159 counties are without a pediatrician, 82 counties are without an obstetrician and 90 are without a psychiatrist.

According to the Georgia Health Care Workforce Commission, 20% of health care workers in the state are over age 55 and looking to retire in the next 10 years. About 4% of the health care workforce leaves annually and is not being replaced by new graduates.

In recent years, the Medical Association of Georgia and other physician advocacy organizations have resisted efforts to widen the scope of what some health care practitioners can do. Some association members have opposed proposals to create a similar assistant physician licensing pathway for medical school graduates not yet matched with residency programs.

When the occupational licensing committee issued its final report last week, its 11 recommendations did not address foreign-trained doctors, but they did include expediting the licensing process for advanced practice registered nurses, and “moving toward” universal recognition of out-of-state licenses, including for medical professionals.

The committee also recommended adopting a model similar to the Military Medics and Corpsmen Program in place in Virginia since 2017, which allows veterans with qualifying military medical experience to continue to practice without having to go through the state’s civilian education and licensing process.

“That’s something I really want to dig into,” said Sen. Larry Walker III, R-Perry, who chairs the committee, and whose district includes Robins Air Force Base. “And hopefully we can get a bill on that, because Virginia is already doing it, and it’s proven to be successful. And we do have a physician shortage, no question about it, big time. But we also have a nursing and allied health care shortage that is as pressing if not more, and I feel like that’s where this can really help your hospitals and your clinics and rural communities, too.”

Walker said he’d also like to see the Legislature spend some more time looking at expediting medical credentials for foreign-trained doctors, but is “hesitant to champion it because of a lack of full confidence and understanding.”

“None of us want to enact a law that ends up backfiring and somebody has an adverse outcome, because we got lax on our oversight. So the natural default is to leave it like it is. That’s the safest,” he said. “But I would argue that you have people probably dying in rural parts of Georgia, because they’re not getting care. And even if it’s not the most renowned surgeon in the world, and the best, still a competent, trained surgeon would be better than none, right?”

Through Senate Resolution 85, the occupational licensing committee was charged with reducing or eliminating licensing requirements that inhibit economic mobility, limit job prospects and hinder small businesses. Walker said recent court cases dictate that “the state has to have a clear and compelling reason to limit people’s ability to earn a living by requiring a license, and the burden’s kind of on the state to prove that it’s to protect the public — public safety, health or welfare. And so that’s the lens that we’ve been looking through.”

The recommendations in the report “are basically the low-hanging fruit that we hope we can get some consensus on when it comes to legislation,” he said. “Of course, it’s just a starting point. When a bill drops, that’s when the real work and debate begins.”

Among the committee’s recommendations is to “sunset” or end regulation of occupations where requiring a license doesn’t seem to protect the public. It names some specialties within the beauty industry, such as makeup artists and manicurists, as well as librarians and low voltage electricians.

That was hopeful news to Scott Self, an information technology professional in Lawrenceville who said he was recently pursuing a low voltage technician license until he found the requirements to be too time-consuming and costly.

An Air Force veteran, Self said he trained and worked as a satellite communications and IT specialist in the military for 13 years, and did similar work as a government contractor for 11 years at military installations in the Philippines, Italy and Qatar.

While he was approved to do low- and high-voltage wiring, as well as complex networking and cybersecurity jobs for the Department of Defense, Self learned when he moved back to Georgia earlier this year that he’s not allowed to perform relatively simple tasks such as installing a residential security or video surveillance system, because he lacks a low voltage license.

To get one, he said, he would have to put his growing IT business on hold, and work for three years under a Georgia electrician who holds a low voltage license, as well as pass the low voltage electrician exam and obtain three letters from contractors vouching for his skills and expertise.

“That’s unrealistic and kind of ridiculous” to expect someone with his level of experience and skills to do, said Self, who estimated he would go from currently making $50 to $150 an hour as a general contractor — depending on the job, to earning $20 an hour as a low voltage tech.

For now, he said he intends to “keep subbing out the LV [low voltage] jobs I get to people who do hold that license, and taking a hit on profit. I’m happy to hear that the state is doing something to address the problem. I want to be an IT business general contractor who’s fully licensed for all of the work my company does, the guy with the white hat who’s calling the shots.”

Read these related stories:

Have questions, comments or tips? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected].

X @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Newly minted Senate Minority Leader Harold Jones II: ‘I’m not the typical back-slapping politician’

Nearly 10 years into legislative life, Sen. Harold Jones II wouldn’t change anything about the experience. “I love every minute of it. Even when I hate it, I love it,” the 55-year-old Augusta Democrat told State Affairs. Come January, Jones will add another role to his legislative duties: Senate minority leader, a job held for …

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …