Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoState agencies are bleeding staff and seeking younger workers

The Department of Natural Resources is seeking more game wardens to keep hunters, hikers and boaters safe and on the right side of the law. (Credit: Department of Natural Resources)

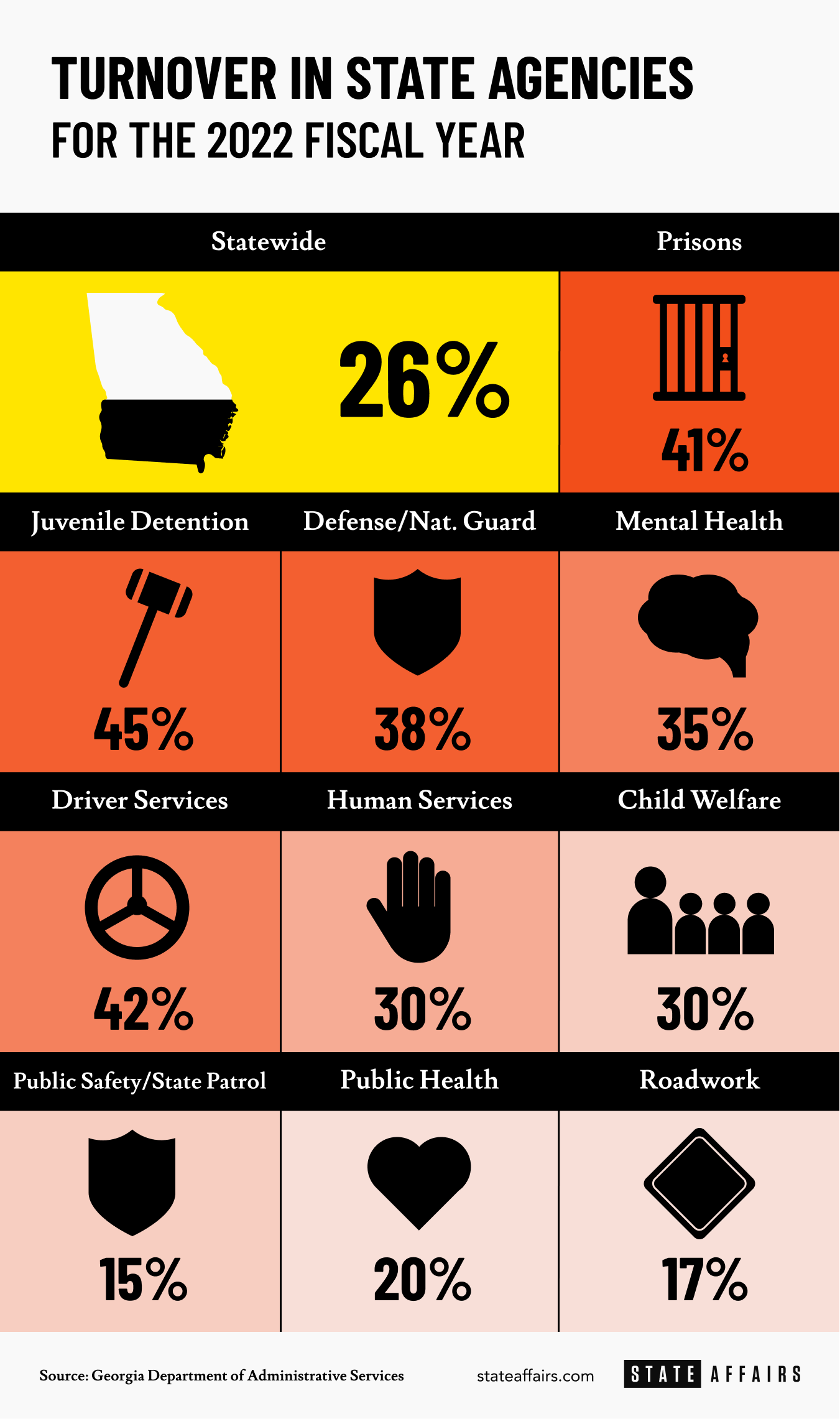

Job turnover among Georgia state employees is at an all-time high — 26%, leading to compromised services in some departments, heavier workloads and more stress for the remaining employees.

State officials are trying new ways to draw people into public service and to keep them longer.

What’s Happening

The Georgia Fiscal Year 2022 Workforce Report, which ran through the end of June 2022, shows the continuation of a six-year trend: More than 20% of the state’s workers are leaving their jobs.

Georgia had a staffing gap — new hires minus terminations — of 1,891 workers last year, and is down 12,100 workers over the past 10 years.

Certain departments are hurting more than others. Juvenile justice, corrections and driver services saw more than 40% turnover, while more than a third of workers in social service, child welfare and behavioral health departments quit their jobs.

Public safety and transportation jobs were more stable, with 15% and 17% turnover, respectively. The reasons that people are leaving public service jobs are varied; some tied to the challenging nature of the work, and some the result of market forces and long-term demographic trends.

Prison guards, juvenile detention and child welfare workers have heavy caseloads and not enough resources, which can lead to burnout, said Al Howell, deputy commissioner of the Human Resources Administration in the Department of Administrative Services (DOAS).

Child welfare work is particularly challenging and stressful. “The pay is low, and we hire young folks who may not know what they’re getting into, and many find it hard and heart-breaking,” Polly McKinney, advocacy director for Voices for Georgia’s Children, a child advocacy organization. “People they’re trying to help are complicated, and even when they’re successful, it can provide secondary trauma to the case workers.”

Juvenile detention officers, who earned a starting salary of $37,700 last year, have an “insanely high” turnover rate, McKinney said. In 2022, that was 96% for entry level staff, and 73% for all juvenile corrections officers, according to the Department of Juvenile Justice annual report.

The private sector pays better, Howell said. He’s hopeful that the $5,000 cost of living increase for most (84%) of the state’s 68,000 employees approved by the Legislature last year, along with the $2,000 increase in fiscal year 2024, will make people feel “more valued,” and help turn the tide of terminations.

Another challenge facing state employers is the aging state workforce. Many older employees are nearing retirement age. About 9% of 61,400 executive branch employees will likely retire within the next year, and 20% may retire in less than five years, according to the workforce report.

The state is working to recruit people of younger generations. Millennials, also known as Generation Y or “digital” workers (age 25 to 41), who now make up a third of the U.S. labor force, represented slightly more than half of new state hires last year, and Generation Z (24 and younger) represented 13%.

But many of them didn’t stick around. The turnover rate was 28% for millennials and 47% for Gen Z.

“They tend to stay less than 12 months, the ones that do leave,” said Howell. “And that’s disturbing, because they make up about 40% of our workforce.”

The Department of Administrative Services is trying to figure out what’s making younger workers leave so quickly, and what will motivate them to stay longer.

“Gone are the days when people will stay 10, 15, 20 or 30 years,” Howell said. “The average tenure now is about four years. So when we talk about retention, we’re not talking about trying to come up with strategies to keep people for double-digit years. We’re trying to think of ways to keep them one, two, maybe three years longer.”

Why It Matters

The heavy churn in some departments inevitably means poor service delivery.

Child and Family Services workers frequently say they are swamped and struggling to keep up with child abuse and neglect cases.

Last December, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that the state’s child welfare ombudsman wrote a letter to Child and Family Services Commissioner Candice Broce identifying “15 systemic breakdowns” within the agency and alleging that its workers “are no longer adequately responding to child abuse cases.” The AJC investigation found that the department’s caseworkers “are leaving their jobs in droves, fueled by low pay, frustration with leadership, and exhaustion from increased workloads, according to state human resources reports.”

When thousands of people waited weeks to receive their Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or food stamp benefits, last November, DHS blamed the delay on “inflation and workforce shortages,” saying it was taking its reduced staff longer to process a higher volume of cases.

Violent fights, untreated medical issues, deaths and suicides among people incarcerated in Georgia prisons have increased in recent years. Many prison guards quit because they feel outnumbered and unsafe, further perpetuating the problems faced by the remaining corrections personnel.

Even departments with seemingly less built-in stress, such as Driver Services, are seeing high (42%) turnover. The department has lost over half its customer service staff since 2018, including the ride-along driver examiners, who conduct license tests for new motorists and commercial truck drivers. Last year, Driver Services pivoted to self-service license renewal kiosks, which has helped ease long wait times in the department’s offices.

What’s Next

Georgia isn’t the only state struggling to keep employees.

According to a national 2022 survey of local and state government employees by MissionSquare Research Institute, a nonprofit research firm, 41% are considering changing their jobs in the near future. The majority — 64% — are “extremely worried or very worried about inflation making it hard to keep up with the current cost of living.”

Among those state workers who were considering changing jobs, the top reasons included desire for better salary and benefits, more job satisfaction and work-life balance, and feelings of burnout, said Joshua Franzel, the managing director of MissionSquare.

Government agencies are facing the same retention issues as private sector employers – younger generations don’t expect to stay with an employer for life, or even for very long, said Franzel. The lure of the public sector, historically, has been that while salaries can’t compete with the private sector, government jobs offer more generous retirement and health benefits, he said. But younger workers, who tend to be healthy and not yet thinking about retirement, place more value on other aspects of the work.

That includes how meaningful the work is, said Franzel. Another survey of recent college graduates entering public service jobs showed that “top of the list for them is meaningful work and mission alignment with the organization,” followed by workplace culture, he said. Compensation and benefits came in third.

So state employers, who may not be able to wow applicants with compensation packages, “should emphasize the accomplishments you can take pride in by taking on a public service role,” said Gerald Young, a senior policy analyst with MissionSquare. “And they should message it in a way that resonates with that audience.”

Georgia has made some headway on compensation. The $5,000 cost of living adjustment salary increases for Georgia state employees in FY 2022 bumped the median executive branch salary to $34,185, up 10% over the previous year, and the median salary for state workers overall rose to $44,637, a 15% increase. And a $2,000 salary increase will show up in paychecks starting this July. Some law enforcement officers will receive an extra $4,000.

The Department of Administrative Services conducted a “midterm snapshot” looking at workforce data from July 2022 (when the $5,000 cost of living adjustment kicked in) to January 2023, and found that new hires exceeded separations for the first time in five years, with a net gain of about 1,000 workers. Howell said if that trend continues, turnover by the end of FY 23 may drop to 21%.

“So we may see some relief for this hole-in-the-bucket syndrome, where more people are leaving than are hired,” he said.

State agencies are also working on developing savvier ways to connect with potential public service workers, such as developing campaigns on social media, digital billboards, mass transit and radio.

In an Instagram ad featuring a Georgia State Patrol car rolling down the road, its swirling blue lights a beacon on a dark, foggy night, potential state troopers are invited to “Be The Light In The Darkness.” Facebook and TikTok reels also emphasize the “0 to 120” miles per hour capabilities of the patrol’s sporty new 2022 Chevy Camaros, which make it easier to catch up to speeding vehicles. All the ads lead to a web page to sign up for the next trooper training class and a $56,350 starting salary.

Pounding rock music and quick cuts of Department of Natural Resources workers four-wheeling in the woods, rescuing stranded hikers in the mountains via helicopter, zooming along lakes in speed boats and pursuing various ne’er-do-wells with sniffing dogs, feature in this recruitment video, which asks, “Do you have what it takes to be a Georgia game warden?”

Howell, of the Department of Administrative Services, said, “There’s kind of a negative public image about law enforcement, rightly or wrongly, that’s out there. And being able to overcome that, and change that, there’s a lot of discussion and work around that right now.”

In recognition that “we can’t address all the jobs and problem areas,” he said the state is focusing first on five key job areas: law enforcement, information technology, social services, accounting and procurement.

DOAS is partnering with the Department of Education, the Technical College System of Georgia, the University System of Georgia and the Carl Vinson Institute of Government on a new Workforce Strategies Initiative to better understand why workers are leaving, and to develop more effective recruitment and retention strategies.

One outcome so far: six agencies in Georgia employ law enforcement officers, and now they’re collaborating on recruitment instead of competing against each other, said Howell. They’re doing joint job fairs and sharing data and insights on applicants.

In an effort to expand the overall applicant pool, DOAS is examining whether a college degree is necessary for about 1,400 state jobs. Only 28% of Georgians over the age of 25 have a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“We’re looking at what people achieve through experience; maybe it’s through the military, maybe it’s through technical school, maybe it’s on-the-job training,” Howell said.

The state is also looking at alternative pathways to qualify people for tech jobs, such as certifications from Google, Microsoft and a variety of technical schools and programs.

Senate Bill 3, the Reducing Barriers to State Employment Act of 2023, which passed last session, empowers the agency to make those changes. Georgia joins eight other state governments that have similarly reduced job requirements, including Maryland, Ohio, Utah, Colorado, Pennsylvania, Alaska, North Carolina and New Jersey.

The human resources staff at DOAS is also encouraging state agencies to fast-track promotions and raises for deserving workers “to provide them with a sense of career progression,” said Howell.

As they try to adopt private sector practices, Georgia government agencies must find more ways to change their slow and lumbering bureaucratic ways, say HR experts.

What most turns off millennials and Gen Z job seekers from entering the public sector is “the longer hiring process and decision timeline,” said Franzel.

He has one suggestion in particular for the state of Georgia: Use a mobile app for hiring.

Do you have insights, tips or questions about working for state government? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @JOURNALISTAJILL or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Check out who’s hiring in state government.

Related:

Header image: The Department of Natural Resources is seeking more game wardens to keep hunters, hikers and boaters safe and on the right side of the law. (Credit: Department of Natural Resources)

Newly minted Senate Minority Leader Harold Jones II: ‘I’m not the typical back-slapping politician’

Nearly 10 years into legislative life, Sen. Harold Jones II wouldn’t change anything about the experience. “I love every minute of it. Even when I hate it, I love it,” the 55-year-old Augusta Democrat told State Affairs. Come January, Jones will add another role to his legislative duties: Senate minority leader, a job held for …

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …