Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoUpdate, May 10, 2023: After much negotiation the Legislature voted to fully fund HOPE scholarships, as the governor had requested. HB 249, which increases the total amount of need-based college completion grants to $3,500 from $2,500, was also passed in both chambers, but was vetoed by Gov. Brian Kemp in May. HB 310 did not advance in the House, but a similar bill, HB 607, which lowers the ACT score required for a Zell Miller Scholarship, did pass and was signed by the governor.

ATLANTA — When Gov. Brian Kemp announced last month that he planned to fully fund the HOPE Scholarship in fiscal year 2024 with a $61.5 million increase to the state budget, Rep. Stacey Evans, D-Atlanta, was among those in the Legislature loudly cheering.

Evans has been lobbying for over a decade to expand HOPE (Helping Outstanding Pupils Educationally), aiming to steer the program back toward its origins: a state lottery-funded program designed to make college affordable for Georgia residents.

“I am thrilled about the direction we’re going, and truly grateful to see these funds restored,” she said. “But there is more we need to do for our students to be able to make it through college going forward.”

While Kemp’s promise to fully fund the HOPE Scholarship has been met with wide bipartisan support, the governor’s proposal only fully funds the program for one year — from July 1, 2023, to June 30, 2024. The funding will mean an extra $444 per year, on average, for full-time students.

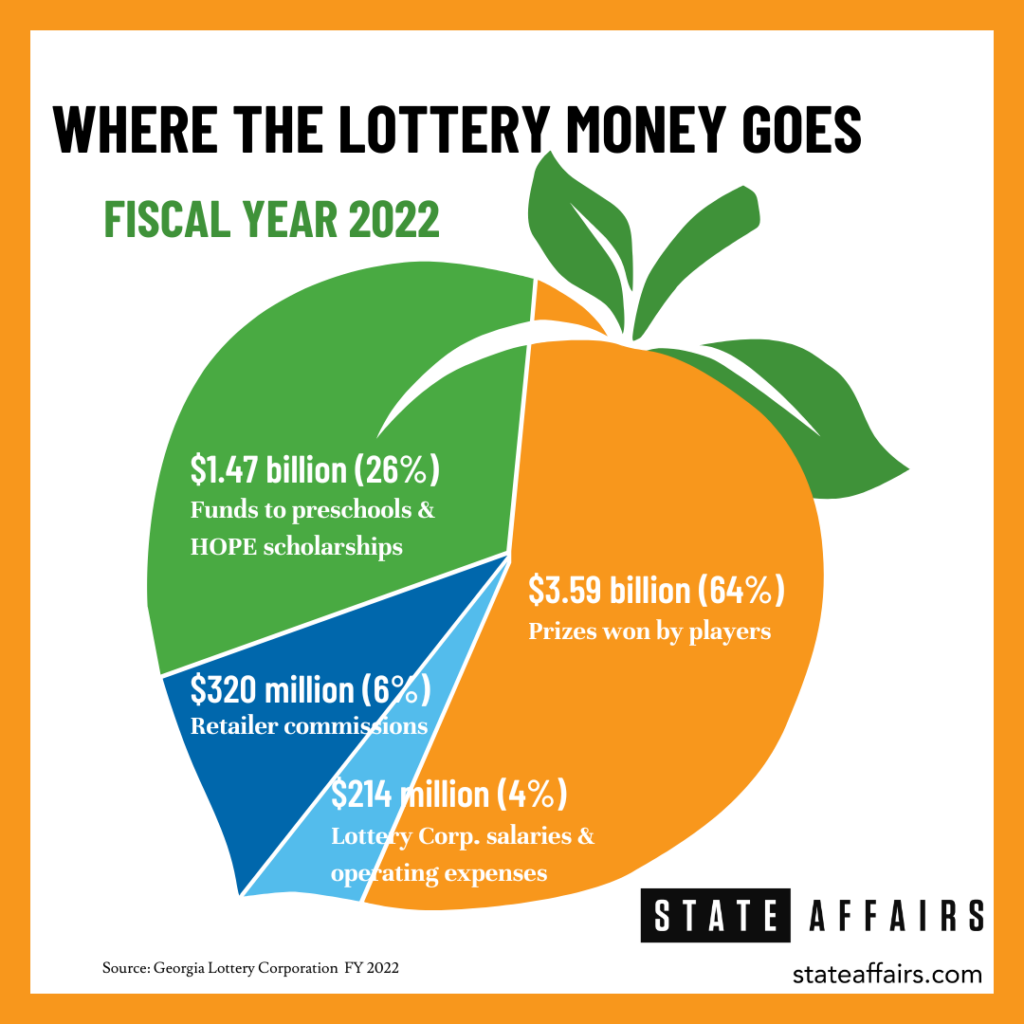

As the Georgia Lottery-fed education reserve fund swells to $1.9 billion and college enrollment continues to drop, legislators, education advocates, workforce development experts and families have expressed concern that seemingly fewer students from low-income families as well as Black and Hispanic children are being awarded scholarships.

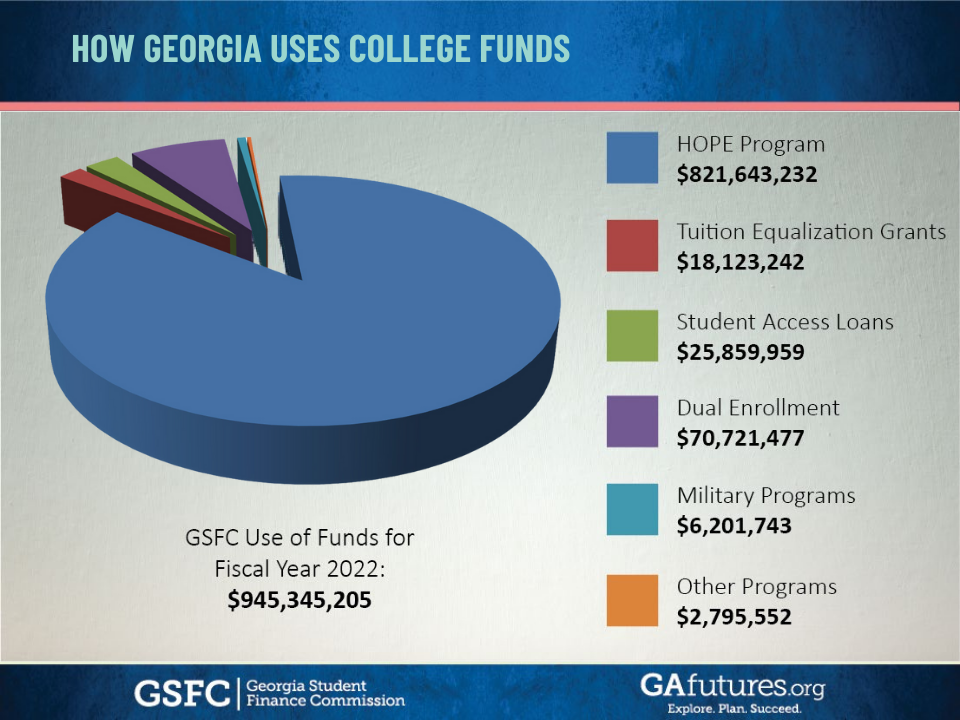

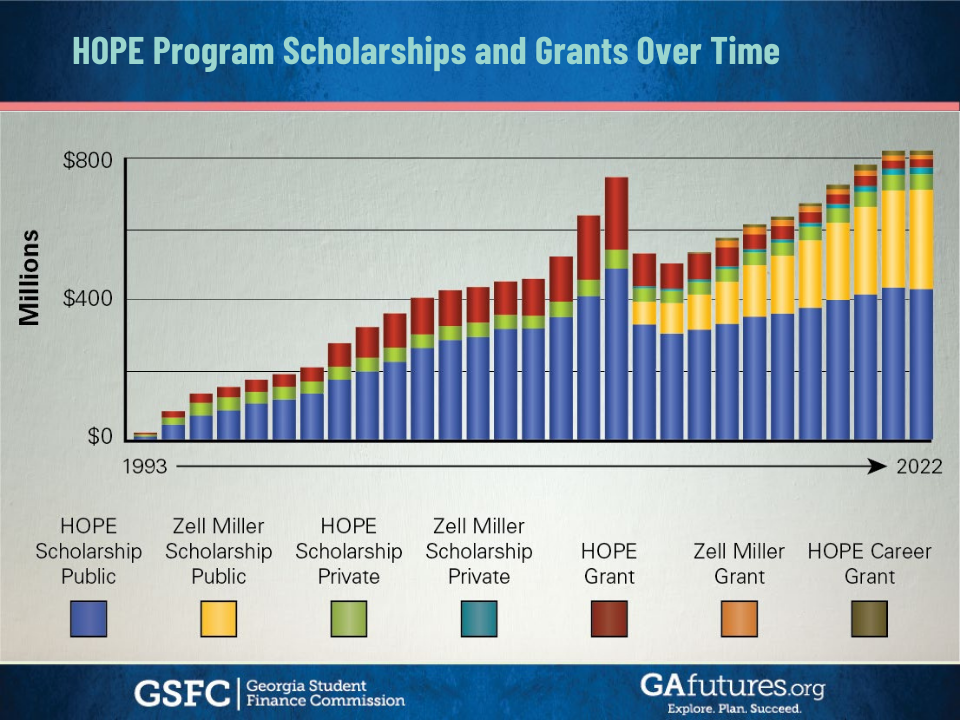

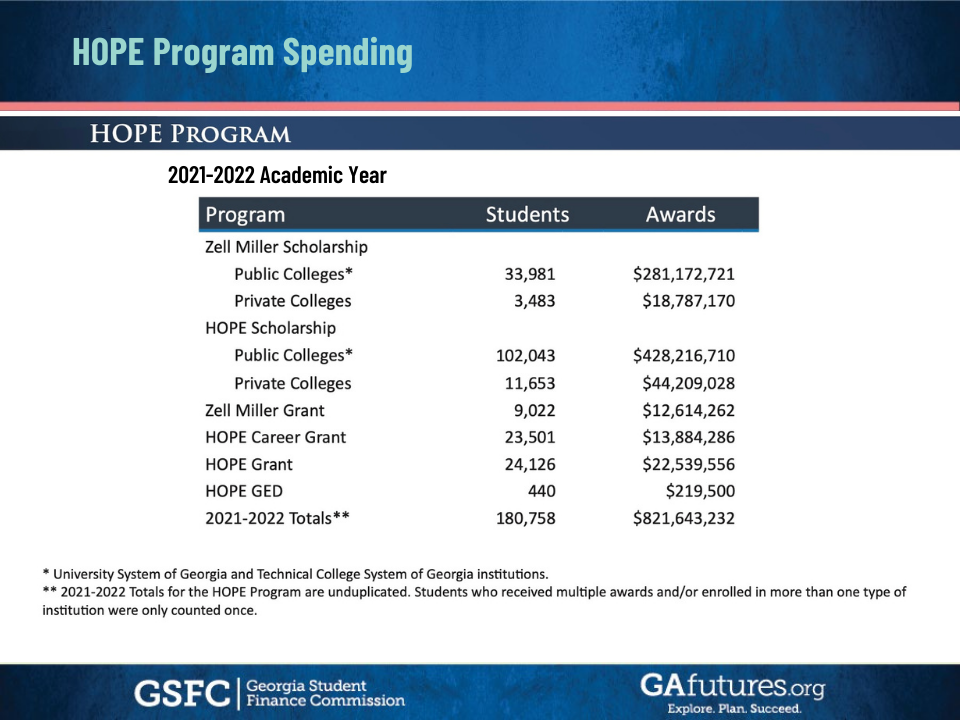

In fiscal year 2022, the Georgia Student Finance Commission (GSFC) awarded close to a billion dollars — $945 million — to Georgia students, to fund five main programs: $472 million for HOPE Scholarships, $300 million for Zell Miller Scholarships, $23 million in HOPE Grants, $14 million in HOPE Career Grants and $13 million in Zell Miller Grants. GSFC also doled out $26 million in student loans.

But somewhere along the way, critics say, the HOPE program became a two-tiered scholarship award, evolving in ways that significantly affect who gets access to college funds.

HOPE began in 1993 with the creation of a statewide lottery to fund pre-K and higher education programs. It had a simple premise: earn at least a B average in high school, maintain that in college, and if you’re a Georgia resident, your college tuition, fees and books are covered. It was aimed at families of modest to middle class means, with a family income cap of $66,000. That cap was lifted in 1995, drawing applicants from all economic levels, who began snapping up the scholarships.

A key inflection point in the program came in 2011, when post-recession economic pressures — lower lottery revenues, higher college costs and an increased demand for scholarships — threatened to deplete the lottery reserve. In response, legislators enacted new academic requirements for the scholarship and created a new, full-tuition program known as the Zell Miller Scholarship.

The Zell Miller required a 3.5 high school GPA, a minimum number of academically rigorous courses and a 1200 SAT (or 26 ACT) score. The bar to receive a HOPE Scholarship still included a 3.0 high school and college GPA, but would only cover a portion of tuition (ranging from 80% to 90% in recent years). Books and fees were no longer covered by any of the scholarship programs.

Since its creation, Zell Miller Scholarship recipients have been pulling an increasingly larger piece of the HOPE pie, and fewer funds are now going to Black and Hispanic students from low-and middle-income families.

A 2021 study by the Georgia State University (GSU) Child & Family Policy Lab showed that white students are six times more likely than Black students to enter a USG school with a Zell Miller Scholarship. Students from families with low incomes and federal Pell Grant recipients are significantly less likely to gain and more likely to lose both Zell Miller and HOPE scholarships.

While 83% of students from households with annual incomes above $100,000 enter Georgia colleges with a HOPE or Zell Miller scholarship, only 54% of students with a family income of $30,000 or less enter college with one.

“The irony, of course, is that low-income people in Georgia are disproportionately funding the HOPE scholarships through purchase of lottery tickets,” said Ross Rubenstein, a professor of education and community policy at GSU and a co-author of the study.

“When we looked at who plays the lottery and how much they spend relative to who gets benefits from lottery-funded programs — if it’s a merit-based college scholarship program, of course it’s going to be skewed towards middle- and upper-income households. We found that lower-income households were spending a higher share of their income and on average spending more money on an absolute basis on the lottery,” said Rubenstein. “So you have where the money is coming from, and where it’s going, and it’s a very regressive way to raise revenue.”

At Maynard Jackson High School (MJHS), counselor Sakari Balam is on a team of five who support 1,450 students from a diverse array of socioeconomic backgrounds — “the haves, the have nots and the in-betweens,” said Balam. They work with students beginning in ninth grade to help them identify their college and career interests, introducing students to the Georgia Futures website, the portal through which financial aid forms, transcripts, Common App essays and college dreams flow.

The saving grace for many students who are “on the cusp, with a 2.9, or maybe a 2.5,” said Balam, is that “they can get money from Achieve Atlanta,” a nonprofit that provides need-based scholarships to low-income, predominantly Black and Latino students in Atlanta each year. Awards range from $1,500 to $5,000 and require a 2.5 GPA.

“I don’t know what other school districts are doing, you know, in helping these kids to close that gap, because I can’t imagine not having something like this in place, in addition to the various scholarships and businesses that we’re always trying to connect them with,” said Balam.

Despite their best efforts, some students do fall through the cracks.

Alayna Blash is a parent of a sophomore at Maynard Jackson and the president of the MJHS Go Team, which includes parents, teachers and community members. In 2018, her son Niles was a senior at the school, and struggling to secure financial aid with a 2.9 “HOPE GPA” (a GPA calculation that factors in “rigor” courses like advanced science, math, AP English and foreign languages, which are weighted more heavily than other basic courses).

“He just missed out on the HOPE Scholarship, and we didn’t know about a lot of other help he could have gotten,” said Blash, who said she found navigating the Georgia Futures portal and the whole financial aid process “bewildering” at the time, despite the fact that she works at Spelman College as associate director of student success.

Niles ended up going to Clark Atlanta University, a historically black, private college where tuition and fees are $12,000 per year, thanks to a tuition credit available through his mother’s job affiliation with the Atlanta University Center. Niles got a small HOPE grant that was “just enough to cover his books” each semester, Blash said. And he’s living at home until he graduates this year because they can’t afford for him to live on campus.

Blash said she’s better prepared now to help her son Marcus, who’s a good student and an athlete, to get a stronger aid package. But she worries about other Black students at Maynard Jackson and other Atlanta Public Schools.

“You know, my concern is always equity,” said Blash. “And if I just think about the eligibility requirements for HOPE, and who at my school [is] in those rigor courses, we know we have a gap there. There’s a disparity. And that’s something that our principal and the team are working on. Because if our Black students are not in the courses, then no, they’re not getting HOPE. And I do think the state should use the lottery money to expand HOPE to meet the need that programs like Achieve Atlanta are meeting because there’s a tremendous need among students who aren’t going to get that 3.0.”

In an effort to level the playing field for students, Rep. Evans, who sits on the House Higher Education committee, is co-sponsoring with Rep. David Wilkerson, D-Powder Springs, House Bill 310, which gets rid of the SAT/ACT score requirement for Zell Miller scholarships. And Evans’ bill HB 157 repeals the Zell Miller grant program altogether.

Evans noted that many students who don’t qualify for a Zell Miller Scholarship have 3.5 or better GPAs, but don’t have high enough standardized test scores, “which is not necessarily the best indicator of college success. It certainly wasn’t for me. I had a 3.8 GPA but barely a 1000 on the SAT. Under HOPE as it exists today, I would not qualify,” she said.

“So many people in the majority just can’t get past wanting to insert some sort of merit element into financial aid,” said Evans. “It’s frustrating. There are a lot of C students in Georgia, and a lot of colleges in Georgia that accept them. I don’t know why we don’t want to help them.”

Evans also introduced HB 316 last week which would mandate (by law, and not just per the 2024 budget) that HOPE grants, which fund diploma and certificate (but not degree) programs, cover the full cost of tuition for an academic year. In recent years the grants only partially funded tuition. And HB 157 calls for HOPE grants to start covering tuition for two-year associate degree programs at technical schools, a change the state Office of Budget and Planning estimates would cost $25 million in 2024.

A call for need-based scholarships

Many people in Georgia have been calling for years for the state to add more need-based college funding into the mix of merit-based financial aid available. Georgia is currently one of only two states in the country that does not have a comprehensive need-based scholarship program.

“We are absolutely missing the mark with our deep love relationship with the HOPE Scholarship and the lack of need-based aid,” said Ashley Young, an education policy analyst with the liberal Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI). While Georgia’s HOPE program is fourth in the nation in the total amount of scholarship money it gives to students “and that’s something to be proud of, that does not make it an equitable system,” she said. The HOPE program has awarded $13.7 billion to 2.1 million students since 1993.

“The HOPE Scholarships largely benefit students who were already on track to attend college,” said Young. “Whether they are second- or third-generation college student status, or already in a place to financially afford college, they have an advantage. When we invest more in merit-based scholarships, we invest for certain students to have options. It’s like, ‘So do I want to go to GSU versus Georgia Southern versus West Georgia?’ Need-based aid is about access, and determines whether someone can afford to attend college at all.”

A survey by GBPI in 2020 found that 75% of Georgians support a need-based college financial aid program

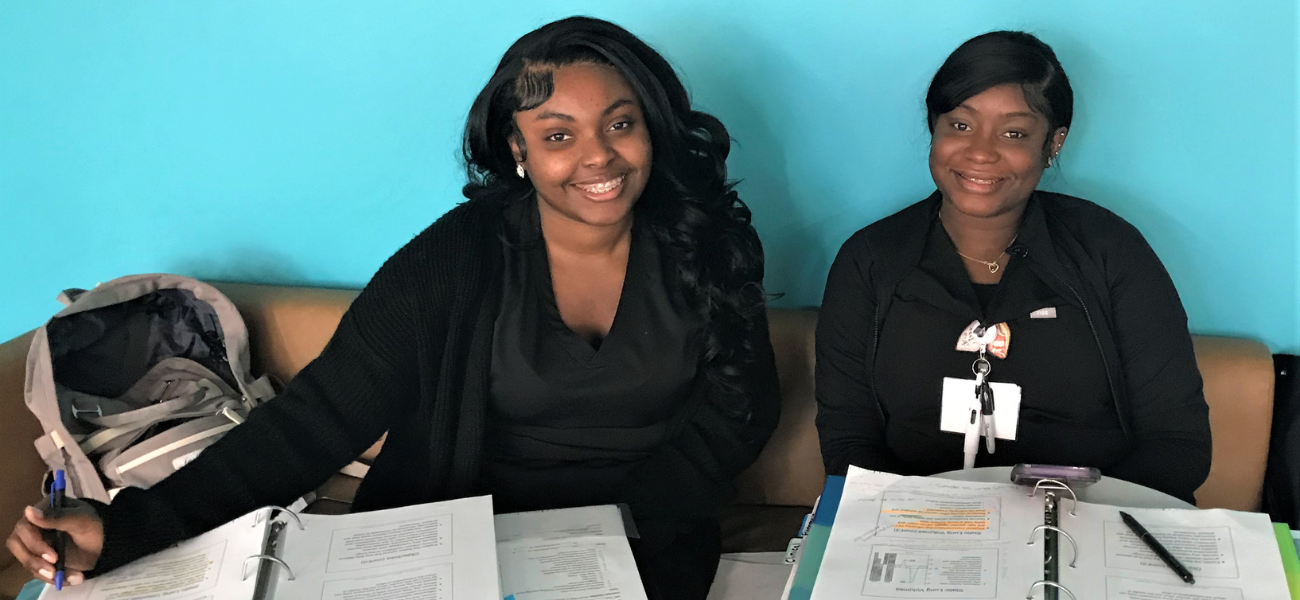

Kayla Daniel, 21, is among those students from a low-income family who are stretched to afford college. A student at Gwinnett Technical College in Lawrenceville, she’s studying to be a respiratory therapist, in a two-year degree program. She recently transferred from a four-year nursing program at nearby Georgia Gwinnett College (GCC) to cut costs. Though she had a federal Pell Grant and a HOPE Scholarship at GCC, and lives with her parents to save on room and board, she said the $13,000 annual cost was too much for her and her family to cover.

The tuition at Gwinnett Tech is less expensive — $1,850 per semester, plus $300 for used books and about $200 a month for gas to commute from her home in Loganville, 45 minutes away. Though she worked through the holidays full-time at Macy’s, she said she doesn’t have time for a job now.

“I knew that once I got into this program, I really wouldn’t have time to work,” said Daniel. “All my time goes into studying, and we have two or three tests every week. I don’t have time to be working on some job when this is supposed to be my future.”

Despite the college credits and 3.5 GPA she came in with, Daniel said she hasn’t yet qualified for a HOPE Scholarship at Gwinnett Tech and has taken out a $4,000 student loan for this school year, debt added to the $1,900 she already has on a credit card she uses solely for school expenses. Daniel said she’s worried about the mounting interest but is determined to get her degree next year and join the workforce where her skills are in high demand.

Her classmate Yancka Denis, 26, is in a similar situation, pursuing a respiratory therapy degree while carrying about $20,000 in student loan debt after transferring from a private nursing college. She lives with her aunt nearby, paying $600 a month in utility and cable bills, and $300 a month on a car loan. She works on weekends at an assisted living facility, tending to elderly patients with memory loss.

“It’s a lot to juggle, and I do get tired sometimes,” said Denis. “But I know I have good job prospects at the end of all this.”

Targeting high-demand career tracks with more lottery funding

What often goes along with faltering tuition and debt payments is a failure to graduate, a tragic outcome for any student, and particularly those who began their college careers with HOPE scholarships.

According to the GSU study of merit-based scholarships, more than 120,000 students will start a bachelor’s degree program in Georgia with a HOPE or Zell Miller scholarship. Twenty percent of students who enter with Zell Miller Scholarships will drop to HOPE or lose their scholarship altogether, and 30% of students entering with HOPE Scholarships will lose them. Most often it’s due to not maintaining the required GPA.

“We continue to see a really large percentage of our graduating students with relatively large amounts of college debt,” said Dana Rickman, CEO of Georgia Partnership for Excellence in Education, a nonpartisan, nonprofit focused on student achievement and workforce development. “And it’s important to remember there’s a significant portion of students who accumulated a bunch of debt, and then had to drop out, especially among the population who were able to start with a [HOPE] scholarship but lost it.”

The Institute for College Access & Success reports that the average debt load of a college graduate in Georgia in 2020 was $28,000, the third highest in the U.S.

Rep. Chuck Martin, R-Alpharetta, who chairs the House higher education committee, said he’s keenly aware of the loan burdens that many students carry, as well as the state’s shortage of skilled and educated workers.

According to Complete College Georgia (CCG), a USG program, by 2025, more than 60% of jobs in Georgia will require some form of post-secondary education, including bachelor’s and associate degrees, and a variety of industry certifications. But CCG reports that only 48% of the state’s young adults currently hold such credentials.

And the headwinds pushing against the state’s ability to achieve that goal are represented in another reality: college freshmen enrollment in Georgia has fallen by about 7% since 2020. The USG system expects fewer Georgia high school graduates over time due to lower birth rates.

To help financially stressed students stick it out, Martin is sponsoring HB 249, which would make one-time, need-based completion grants of up to $2500 available to students who run out of money after they’ve completed 70% of credits in a four-year program, and 45% of credits in a two-year program. Currently, these grants are funded at $10 million in the governor’s proposed 2024 budget. Martin said he’d like to fatten the completion grant fund by transferring capital out of the student loan program, currently funded at $26 million, “to help more students cross the finish line and avoid taking on more debt.”

When asked by State Affairs about his and the higher education committee’s willingness to use more lottery funds to pull more students who don’t qualify for merit-based HOPE programs into college and career pipelines, Martin said, “There is a sincere effort going on in the workforce subcommittee and higher ed to move the needle on this. We’ve talked about this for a long time, and then COVID happened. As Newt Gingrich used to say, ‘Real change requires real change.’

“We’re looking at applying additional monies toward incentivizing people to finish their education in programs that are most productive,” he said. “It’s probably going to be focused on certain high-demand careers in TCSG and certain fields in USG. There’s just not enough capital to do it for everybody. And frankly giving college tuition to every person that wants to go to college, you’re going to have people that don’t have a focus, and may go into debt with no reward, which isn’t good for them or for the state. But hopefully, we’ll get some more people headed to college and TCSG programs in 2023, and then we’ll come back and look at doing more, incrementally.”

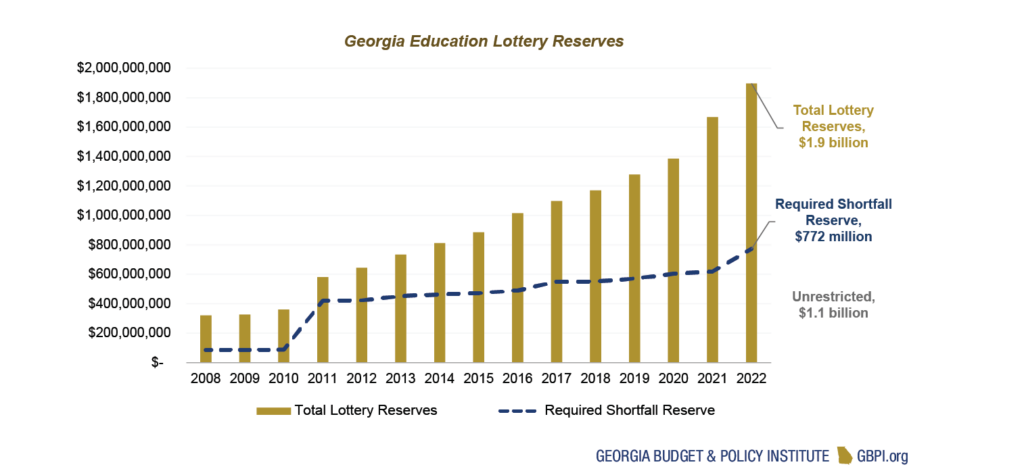

GBPI’s Young said the education lottery reserve fund “has grown tremendously since 2015,” and now stands at $1.9 billion. About $770 million is required in case of a shortfall to be able to fund HOPE programs, she noted, leaving $1.1 billion in unrestricted reserves.

“If we tap the lottery reserve for need-based aid, I understand that there are valid concerns about how that would be sustained,” she said. “It depends on how you determine eligibility for students, how much money we’re giving out each year, and other factors. But I think it is certainly an embarrassment of riches to have this much money and still no broad need-based aid program.”

Have thoughts on how lottery proceeds or other state education funds should be spent or managed? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @JOURNALISTAJILL or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header Image: Gwinnett Technical College students Kayla Daniel and Yancka Denis are both studying to be respiratory therapists. (Credit: Jill Jordan Sieder).

Read more about the HOPE and Zell Miller scholarships.

Know the most important news affecting Georgia

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …