Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoWith HOPE fully funded, how can Georgia students maximize their state scholarship options?

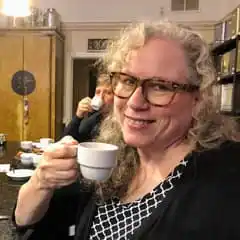

Coffee High School graduate Moises Guzman Jr. and his parents Rocio Navarrete Gonzalez and Moises Guzman Sr., celebrate his $10,000 Live Màs scholarship at the Taco Bell restaurant in Douglas, Georgia, where he works. (Credit: Tacala Companies)

With the HOPE Scholarship now funding college tuition at 100%, many people wonder how long that will last and what the distinctions are between HOPE and the Zell Miller Scholarship, which also fully funds tuition at state public colleges but has more demanding academic requirements. We’ve taken a look at both scholarships and have collected some insights and advice from students, parents, and college funding experts on how to earn, keep and maximize each award.

What’s Happening

Moises Guzman Jr. is a 17-year-old, freshly minted honors graduate from Coffee High School in Douglas, a town in south Georgia with a population just shy of 12,000. He plans to study engineering and business at South Georgia State College this fall, with tuition fully covered by the Zell Miller Scholarship.

“That scholarship really means a lot to me because I don’t know how much money I would be able to raise for college without it,” said Guzman, whose mother works at a nearby cargo trailer manufacturing plant. His father is recently retired from poultry processing. Both immigrated to Georgia decades ago from Mexico. Guzman works at Taco Bell and chips in to help with household expenses. He will be the first in his family to go to college.

The Zell Miller Scholarship, the most prestigious Georgia Lottery-funded college award, requires at least a 3.7 high school GPA and a minimum 1200 SAT, or 26 ACT, score. To keep the Zell Miller award, students must maintain a 3.3 GPA in college. Guzman earned a 4.0 GPA in high school, taking several Advanced Placement (AP) and Honors courses, and got a 26 on the ACT.

He’s among 22 students in Coffee County who earned the Zell Miller Scholarship this year.

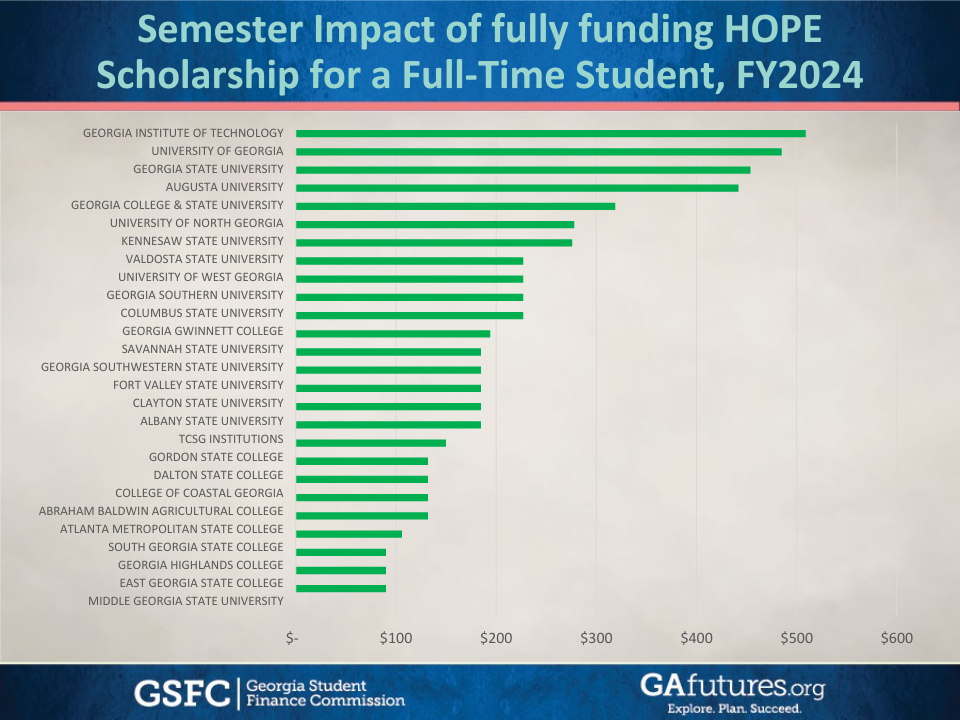

Many more students qualified for the HOPE Scholarship, which has a lower academic bar — a 3.0 high school and college GPA. Over the past decade, the HOPE Scholarship has covered only 80% to 90% of tuition at most of Georgia’s public colleges and universities. This year the Legislature appropriated an extra $47 million to fully fund HOPE for fiscal year 2024. Both scholarships, awarded for attendance at schools within Georgia, will now cover 100% of public school tuition in the upcoming academic year.

Guzman said he didn’t know much about what it takes to get either scholarship until his junior year in high school. That’s when he learned that both HOPE and Zell require students to take at least four “rigor courses,” which include advanced math, advanced science, foreign language or AP, International Baccalaureate (IB) or Dual Enrollment (DE) classes at local colleges before they graduate.

Guzman talked to his high school counselor, who helped him develop a college plan, which included taking three dual enrollment classes at South Georgia State College — algebra, pre-calculus, and English— in his junior and senior years.

He also didn’t know about the difference between a regular high school GPA and the HOPE GPA, which is calculated using only grades from core courses including English, math, science, social studies and foreign languages. The HOPE GPA is what the Georgia Student Finance Commission uses to determine award eligibility. (So, art, PE, and driver’s ed classes don’t count).

Guzman also started working on the SAT his junior year, using free online resources such as Khan Academy and College Board, which offer test prep support and practice tests. He took the SAT twice and scored less than the 1200 needed to qualify for Zell. In his senior year, he took the ACT and scored a 26, the minimum score needed, on his first try. “I did struggle to get that test score,” he said.

Asked if he cares that HOPE Scholarship recipients now earn the same monetary award as Zell scholars, Guzman said, “Everyone here is really happy about it. This is a really small town and not everyone gets to go to college. If you do get one of those scholarships, it encourages you to go, and to be able to afford it. And for me, if I ever do lose Zell Miller, I’m glad I have a backup with HOPE that will still allow me to attend college.”

His sentiments are shared by many students and parents who’ve experienced or witnessed the struggle to maintain either the 3.0 or 3.3 college GPA needed to maintain the HOPE and Zell Miller Scholarships, respectively.

Daryl O’Hare of Roswell is a professional tutor with two daughters who earned Zell Miller scholarships. One just graduated from Georgia Tech, and the other is in her third year at Georgia State. She said the pressure that both of her daughters have experienced to maintain a 3.3 GPA to keep their Zell scholarships has been “intense and stressful.”

At Georgia Tech, the difference between 90% and 100% of a year’s tuition (at 15 credit hours per semester) is currently $1,026, or about $4,100 over four years. At Georgia State, the difference is $894 a year, or about $3,600 over four years. Room, board and fees can add an additional $10,000 to $20,000 per year, at both schools.

With a joint marital income of around $95,000 a year, O’Hare said the savings provided by the Zell Miller Scholarship in previous years has mattered to her family. Her eldest daughter chose to attend Georgia Tech over Northeastern University in Boston, which would have cost $45,000 more per year, all expenses considered.

“My kids knew that we were hyper-focused on making sure that they keep their scholarships,” said O’Hare. “So, you know, at Georgia Tech, there could be one professor who’s just hard as nails. And if they gave you a C, you know, everything would be in jeopardy. So, I think that having the 3.0 for everybody at the 100% rate … I don’t think that my daughters would say, ‘Oh, man, I worked so hard for that. And that’s not fair.’ I think they would be like, ‘Wow, that would take some pressure off.’” (Both of her daughters later confirmed to State Affairs that they agreed).

Not everyone feels that way.

Joshua Keenum of Woodstock has a daughter who graduated from Georgia Tech with a public policy degree this year, maintaining her Zell Miller Scholarship all four years. His son is a rising high school senior who is dual-enrolled at Kennesaw State University with hopes of attending Georgia Tech or another top research university. A math and science standout, he has the stellar grades, test scores and a resume full of AP classes, including math and genetics, to earn a Zell Miller Scholarship.

Keenum, a manager at a chain of fitness clubs, would like to see his kids’ hard efforts rewarded with extra benefits.

“When you see the students who put in more effort and have higher GPAs, they should get greater compensation with these scholarships,” said Keenum. “Why do they need to work as hard if everything is going to be given to them at a lower GPA? Does that encourage more lackluster behavior? I don’t know, but I’m of that hustler mindset, where if I’m going to get a reward, I want to be good at what I do, and not just get by … A 3.0 just does not require the same effort.”

Leaders in the state House of Representatives argued along similar lines during the last legislative session, when they initially approved funding for HOPE at 95% of tuition cost instead of the full 100% that Gov. Brian Kemp had pushed for in his proposed budget. (After some haggling among House and Senate leaders in the closing days of the session, full funding for HOPE was restored, but only for fiscal year 2024).

Helese Sandler, director of college counseling at Savannah Educational Consultants, a private tutoring and academic coaching firm, said she has “a little bit of concern that some kids striving for a 3.7 might now think, ‘I don’t need it.’ But my experience of high achievers is that they’re going after not just in-state scholarships, but all kinds of scholarships and financial aid at public and private colleges across the country, some of which are very selective. I don’t think it’s going to demotivate them at all.”

The fact that the HOPE Scholarship is funding 100% of tuition in the upcoming academic year “means that now, with a 3.0, college is going to be more affordable,” she said. “Those extra few thousand dollars can make a huge difference to some families.”

That’s true for Jakera Lowman, 17, of Garden City, who’s heading off to Georgia Southern University in Statesboro this fall. Her mother, Leslie Lowman, who works as a custodian for Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools, said both the HOPE Scholarship and the federal Pell Grant are “what’s going to make college possible for my daughter,” who plans to live on campus and study nursing. With HOPE fully funded, Jakera will have $500 less in tuition to cover next year and about $2,000 less in student loans when she graduates.

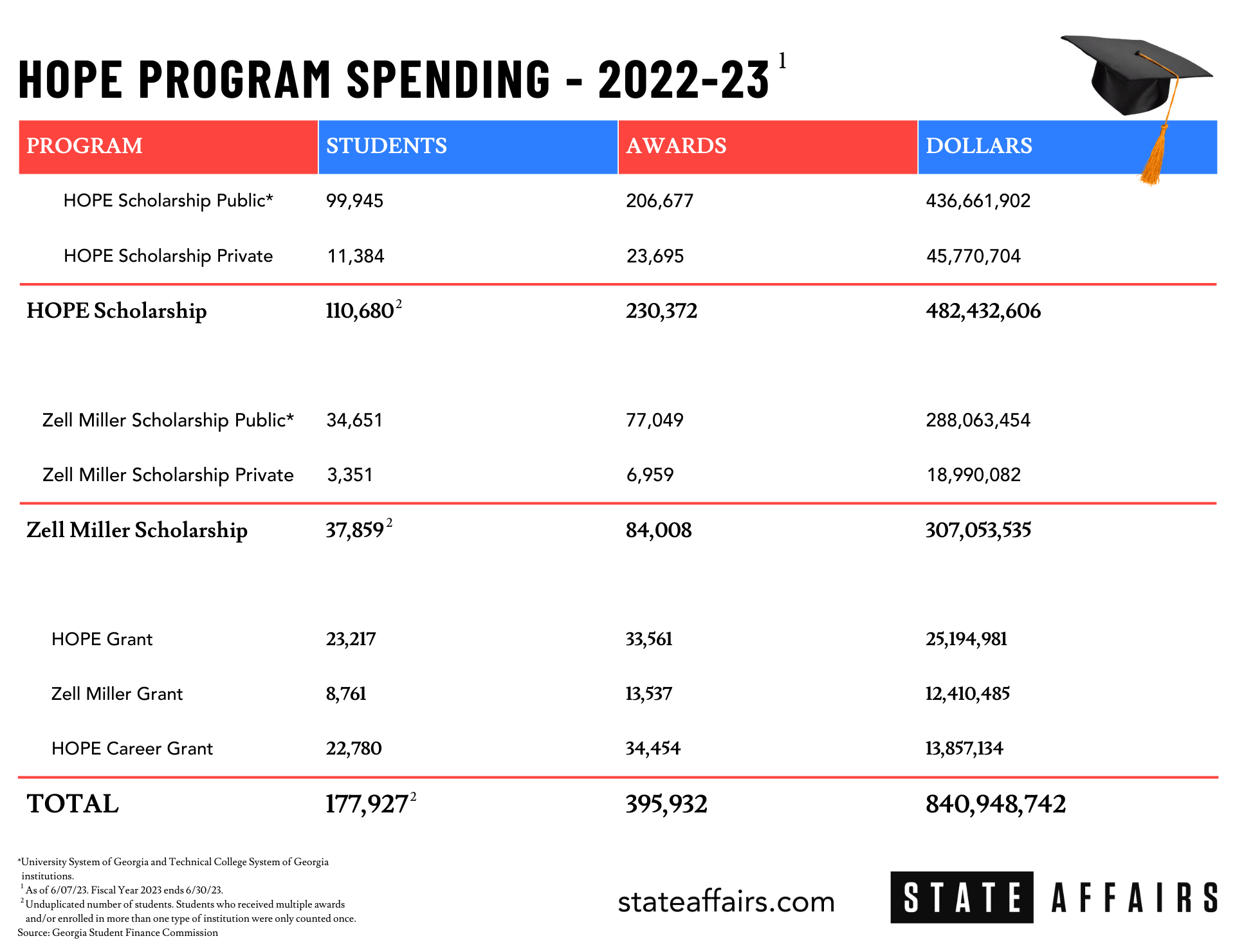

About three times more students win HOPE than Zell Miller scholarships each year. In the 2022-2023 academic year so far, the state has awarded 38,002 students Zell Miller scholarships and 111,329 students HOPE scholarships.

Zell Miller scholars tend to gain admission to, and attend, the larger and more expensive colleges and universities in the state and thus win more tuition money. The average HOPE award was $4,359 per student this academic year, while the average Zell award was $8,110.

Why It Matters

Funding for the HOPE Scholarship and all HOPE tuition assistance programs can change from year to year according to the will of the governor and the General Assembly, noted Lynne Riley, who is president of the Georgia Student Finance Commission, and a former state treasurer and state representative. There is no statutory guarantee that HOPE tuition will remain fully funded.

The HOPE Scholarship program was created in 1993 by then-Gov. Zell Miller, and the award covered 100% of tuition and the cost of books and fees to students who earned a B average in high school and maintained a 3.0 in college. The program proved very popular and helped drive increased enrollment at state colleges and universities.

The Zell Miller Scholarship was later created in response to an economic downturn. In 2011, in the wake of the ‘Great Recession,’ the Legislature reduced HOPE awards after lottery revenues failed to keep up with ever-increasing student demand. The Zell Miller Scholarship, with its more rigorous academic requirements, was introduced as a way to reward high-achieving students with full tuition while cutting the overall costs of the HOPE program.

“I was in the General Assembly when we had to make that call,” said Riley. “That was rough, but it was something where we had to react to the circumstances at the time.”

The Georgia economy is currently strong, and the Georgia Lottery, which funds both pre-kindergarten and higher education programs, boasts a surplus of $1.9 billion, with $1.1 billion in unrestricted reserves. But Riley said because of variable economic conditions, the commission’s primary message to high school students is to “aim high academically.”

“Once you achieve Zell, you can rest assured you’ve earned a 100% award of a current year’s tuition,” she said. “So you protect yourself against tuition increases, and you protect yourself against any reductions in the HOPE award amount in future years.”

Riley noted that students who qualify for Zell Miller scholarships “are highly attractive to our state colleges and universities and are very likely to receive additional scholarships and financial aid” from both public and private institutions.

That’s the case for Moises Guzman, who was selected as a Live Màs Scholar by Taco Bell and won an additional $13,000 in scholarship funds. He said those funds will prove vital if he’s successful in transferring to Valdosta State or a bigger university further away from home in a couple of years. For now, he’s planning to save on room and board by living at home.

And for students who enroll in private colleges and universities in Georgia, there is still an immediate financial benefit to being a Zell Miller scholar. The award amount for HOPE scholarships at private schools is $2,496 per semester, while the award for Zell Miller scholarships is $2,985 per semester, almost $1,000 more per year.

The key to winning either of the HOPE program scholarships is to start early, in 9th grade, to develop a college plan, said Sandler. Students should make sure they’re taking the right mix of classes to qualify for admission to their target schools, as well as scholarships and financial aid.

Jakera Lowman did just that, taking several AP and honors courses while earning certifications in child care and cosmetology at Woodville Tompkins Technical and Career High School. “She set her expectations high and then exceeded them,” said her mother, Leslie.

Jakera said her plan was to maintain at least a 3.0 GPA throughout high school. By her junior year, with a solid B-plus average, she began gunning for Zell. She ended up just short, with a 3.7 HOPE GPA, and an 1150 on the SAT, earning her a HOPE Scholarship and offers from several in- and out-of-state colleges, public and private.

“She took on a lot, and there were nights when she would have anxiety attacks, worrying about her grades in her advanced classes, which seemed to get harder and harder,” said Leslie Lowman. “But I was her cheerleader and I always reminded her that she was trying her best, and that was good enough.”

“The amount of work in the advanced courses can be overwhelming, but college is expensive, and I’m really glad I got HOPE, and I won’t have to go too deep out of pocket to pay for it,” said Jakera.

Even if you shoot for Zell and miss out, maintaining a B or better grade average can also pay off in other ways, said Sandler.

Many colleges in Georgia and other states no longer require the SAT or ACT. But most colleges that offer score-optional admission do require a 3.2 or 3.3 high school GPA, she said.

So students who don’t test well should still keep their grades up in hopes of gaining admission to such schools as Georgia State, Georgia Southern, Kennesaw State and Oglethorpe universities. Many of these schools offer their own grants and scholarships that factor in both academic merit and financial need.

A 3.0 or higher college GPA at the University of Georgia can help students qualify for the Georgia Charter Scholarship, a $2,000 annual stipend. Georgia State offers several renewable scholarships worth $1,000 to $3,000 annually to students who maintain a 3.0.

The Georgia Futures website, where Georgia students apply for college and financial aid, has links to dozens of public- and privately-funded scholarships that high school and college students with a B average can earn.

What’s Next

When the General Assembly convenes in January, it will consider Kemp’s proposed amended fiscal year 2024 and 2025 budgets, which will likely include continued full funding of the HOPE Scholarship. Economists predict another healthy state budget surplus when the 2023 fiscal year ends on June 30, and the Georgia Lottery surplus remains robust. But a decline in state tax revenue collections over the past three months could have some legislators girding for another vigorous debate in the Statehouse over the level of HOPE funding for the next academic year.

Have thoughts on how lottery proceeds or other state education funds should be spent or managed? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @JOURNALISTAJILL or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Read our related coverage:

Header image: Coffee High School graduate Moises Guzman Jr. and his parents Rocio Navarrete Gonzalez and Moises Guzman Sr., celebrate his $10,000 Live Màs scholarship at the Taco Bell restaurant in Douglas, Georgia, where he works. (Credit: Tacala Companies)

Know the most important news affecting Georgia

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

Unlimited Access: Subscribe for just $2.99/mo billed monthly.

Subscribe NowGet unlimited news access

Already a member? Login here

Kemp signs bills on education, health care, taxes

Gov. Brian Kemp signed a slew of bills over the past week or so, including the private school voucher bill long sought by Republicans and a bill that will ease regulations over the construction and expansion of medical facilities in rural areas.

His bill-signing events were clustered into themes: education, health care, military members, human trafficking and Georgia’s coastal communities.

Education

Among the education-related bills Kemp signed was Senate Bill 233, also known as the Georgia Promise Scholarship Act, which provides the families of Georgia students enrolled in underperforming school districts with $6,500 scholarships that can be used toward private school or homeschooling expenses, including tuition, fees, textbooks and tutoring.

“Georgia is affording greater choice to families as to how and where they receive their education, while also continuing our efforts to strengthen public schools, support teachers, and secure our classrooms,” Kemp said, and thanked leadership in the House and Senate for prioritizing passage of the bill, which had failed in a close vote in 2023.

Democrats and many public education advocates who opposed the bill argued it will drain resources from public schools and primarily benefit students from wealthy families.

Kemp also signed Senate Bill 351, sponsored by nine Republican senators, which will require social media companies, as of July 1, 2025, to verify their users are at least 16 years old unless they receive approval from a parent.

House Bill 409, sponsored by Rep. Lauren Daniel, R-Locust Grove, directs school systems to consider not having bus stops where a student would have to cross a roadway with a speed limit of 40 mph or greater. The bill also increases the penalty for passing a stopped school bus to $1,000 from $250.

Kemp noted that Ashley Pierce, the mother of Addy Pierce, an 8-year-old who was fatally struck by a motorist as she boarded her school bus, “passionately advocated for and was instrumental in the passage of this legislation.”

Senate Bill 395, sponsored by Sen. Clint Dixon, R-Gwinnett, states that no school visitor or personnel can be prohibited from possessing an opioid reversal drug such as Narcan and directs schools to maintain a supply. It also allows opioid antagonists to be sold in vending machines and directs certain government buildings to maintain a supply of at least three doses.

Senate Bill 464, also sponsored by Dixon, creates the School Supplies for Teachers Program to financially and technically support teachers purchasing school supplies online. It also creates an executive committee of five voting members within the Georgia Council on Literacy and limits the number of approved literacy screeners to five, one of whom must be available to schools for free.

Health care

The governor chose his hometown of Athens as the venue to sign several bills aimed at improving health care in rural and underserved communities.

Among them was House Bill 1339, sponsored by Rep. Butch Parrish, R-Swainsboro, which revises the Certificate of Need process by which the state determines if and how new medical facilities can be built or expanded. The bill provides for several new exemptions, including psychiatric or substance abuse inpatient programs, basic perinatal services in rural counties, birthing centers and new general acute hospitals in rural counties. It also raises the total limit on tax credits for donations to rural hospital organizations to $100 million from $75 million.

Senate Bill 480, sponsored by Sen. Mike Hodges, R-Brunswick, establishes student loan repayments for mental health and substance use professionals serving underserved youth in the state or in unserved geographic areas disproportionately impacted by social determinants of health.

House Bill 872, sponsored by Rep. Lee Hawkins, R-Gainesville, chair of the House Health and Human Services Committee, expands cancelable loans for certain health care professionals to dental students who agree to practice in rural areas.

Senate Bill 293, sponsored by Sen. Ben Watson, R-Savannah, chair of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, reorganizes county boards of public health and opens the qualifications for the CEO of each county board of health to include either licensed physicians or people with a master’s degree in public health or a related field.

Military members and veterans

Kemp on Wednesday focused on bills to improve military recruitment and provide more work opportunities for veterans and military family members.

House Bill 880, sponsored by Rep. Bethany Ballard, R-Warner Robins, allows spouses of military service members to work under a license they hold in good standing in another state while under the supervision of an existing Georgia medical facility or provider.

Senate Bill 449, sponsored by Sen. Larry Walker, allows military medical personnel to practice for 12 months while a license application is pending, including working as a certified nursing aide, certified emergency medical technician, paramedic or licensed practical nurse. The bill also creates a new advanced practice registered nurse license and makes it a misdemeanor to practice advanced nursing without a license.

Human trafficking

The governor on Wednesday was accompanied by first lady Marty Kemp and other members of the GRACE Commission for the signing of an anti-human trafficking package. It includes Senate Bill 370, which adds certain businesses to the list of organizations that must post human trafficking notices, including convenience stores, body art studios, businesses that employ licensed massage therapists and manufacturing facilities.

Sponsored by Sen. Mike Hodges, R-Brunswick, the bill also allows the Georgia Board of Massage Therapy to initiate inspections of massage therapy businesses and educational programs without notice and requires massage therapy board members to complete yearly human trafficking awareness training.

House Bill 993, sponsored by Rep. Alan Powell, R-Hartwell, creates the felony offense of grooming of a minor and creates new penalties for offenses relating to visual mediums depicting minors engaged in sexually explicit conduct.

House Bill 1201, sponsored by Rep. Houston Gaines, R-Athens, allows human trafficking survivors who received first offender or conditional discharge status to vacate that status for certain crimes, as long as the crime was a direct result of being a victim of human trafficking.

Coastal communities

Earlier today in Brunswick, Kemp signed legislation impacting Georgia coastal communities, including House Bill 244, which amends the laws around how wild game can be hunted and how seafood dealers operate, and House Bill 1341, which designates white shrimp as the state’s official crustacean.

Taxes

Earlier this month Kemp signed several bills related to taxation, including House Bill 1015, sponsored by Rep. Lauren McDonald, R-Cumming, which lowers the state income tax for tax year 2024 to 5.39%, accelerating a multiyear drop in state income taxes that started at 5.75% in 2023 and will continue through 2029.

The Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget estimates the tax cut acceleration will save Georgia taxpayers approximately $1.1 billion in calendar year 2024 and about $3 billion over the next 10 years.

Kemp also signed House Bill 1021, sponsored by Rep. Lauren Daniel, R-Locust Grove, which increases the state’s income tax dependent exemption to $4,000 from $3,000.

House Bill 581, sponsored by Reps. Shaw Blackmon, R-Bonaire, and Clint Crowe, R-Jackson, enables a constitutional amendment (House Resolution 1022) to let voters decide whether counties can provide a statewide homestead valuation freeze, which limits the increase in property values to the inflation rate.

The governor has until May 7 to sign or veto bills passed during the legislative session that ended on March 28. Those he takes no action on will automatically become law.

Legislation signed by Kemp is posted on the governor’s website.

Read these related stories:

Have questions, comments or tips on education in Georgia? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Incumbent candidates for local, federal races likely to be no-shows at this weekend’s primary debates

ATLANTA — One of Georgia’s prominent media organizations is pleading with incumbent state and congressional candidates to participate in its primary election debates slated for Sunday.

For the first time in The Atlanta Press Club’s 30-year debate history, incumbents facing challengers in the May 21 primary have either declined or not yet committed to participating in the organization’s well-known debate series. The possible no-shows include candidates in four Congressional races as well as the Georgia Supreme Court, and the Fulton County District Attorney races.

“This is the first time that we’ve had so many [incumbents] not participate,” debate organizer Lauri Strauss told State Affairs. Strauss declined to speculate why candidates aren’t participating.

Hoping to encourage more participation, the organization issued the following statement:

“The Atlanta Press Club believes it is the responsibility of people running for public office to answer questions from their local media that will help inform voters before they cast their ballots. If a candidate is running for public office, the candidate should be willing to participate in the democratic process, which includes attending debates and fielding questions from journalists and opponents.”

Candidates have until Friday to RSVP.

Strauss said candidates who fail to appear will be represented on stage by an empty podium during the debate.

District Attorney Fani Willis has declined to participate and Democratic U.S. Reps. Lucy McBath and David Scott have yet to RSVP. Strauss said the organization is still in talks with Georgia Supreme Court Justice Andrew Pinson’s staff about his appearance in the debate.

Willis, declined earlier this week to participate, citing constraints around talking about sensitive cases like the criminal prosecution of former President Donald Trump.

McBath currently represents the 7th Congressional District and is now running in the newly drawn 6th Congressional District against two Democratic challengers, Jerica Richardson and Mandisha Thomas. McBath declined to participate in the press club’s general election debate in 2022, forcing her Republican challenger Mark Gonsalves to debate with an empty podium. McBath won with 61% of the vote.

The debates will air live on April 28 on GPB.org, on The Atlanta Press Club’s Facebook page (www.fb.com/TheAtlantaPressClub). It will be rebroadcast in early May on WABE.org.

| Race | Tape and Livestream Sun. April 28 |

GPB-TV Broadcast | WABE Broadcast |

| Congressional District 6 Democrats | 10:00 a.m. | April 29 at 7:00 p.m. | May 1 at 4:30 p.m. |

| Congressional District 13 Democrats | 11:15 a.m. | April 28 at 4:00 p.m. | May 1 at 5 p.m. |

| Congressional District 3 Republicans | 1:00 p.m. | April 28 at 5:00 p.m. | May 2 at 3:30 p.m. |

| Congressional District 2 Republicans | 3:00 p.m. | April 29 at 5:00 p.m. | |

| Georgia Supreme Court | 4:45 p.m. | May 2 at 4:30 p.m. | |

| DeKalb County CEO | 5:45 p.m. | May 2 at 5:15 p.m. | |

| Fulton County District Attorney | 6:45 p.m. | May 1 at 4 p.m. |

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected] and Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram@StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

‘It is nothing short of insane:’ Bill to criminalize squatting signed by governor

ATLANTA — Today Gov. Brian Kemp signed legislation criminalizing squatting, the illegal practice of entering and residing on someone else’s property without their consent.

The Georgia Squatter Reform Act makes squatting a misdemeanor criminal offense, punishable by up to a year in jail, a $1,000 fine, or both. It also speeds up the timeline to evict a squatter, giving landlords and law enforcement more tools to establish that someone is trespassing and to demand that they leave.

“It is nothing short of insane that there are some who are entering other people’s homes and claiming them as their own,” Kemp said in a post on X after signing the bill at the state Capitol. “Thanks to our legislative partners, I was proud to sign HB 1017 — once again making it clear that illegal squatters are criminals, not residents.”

Over the past few years, squatting has become more prevalent in Georgia, with trespassers breaking into vacant homes, claiming tenancy and refusing to leave.

A 2023 survey of institutional investors in single-family rental homes who are members of the National Rental Home Council found there were 1,200 illegally-occupied homes in and around Atlanta. Realtors told State Affairs they’ve encountered squatters in homes for sale and rent in Gainesville, Valdosta and Albany.

Until now, law enforcement in many jurisdictions treated the issue as a civil matter, telling property owners to file eviction actions in court, which could take months or even years to resolve.

The new law directs local law enforcement to issue citations and arrest people accused of squatting if they don’t provide a valid lease or proof of payment within three days. If they do produce such documents, it moves eviction proceedings to magistrate courts, and requires cases to be heard within seven business days after filing.

If the judge deems documents they present to be forged or fake, those accused of squatting could be charged with a felony. And judges can impose more fines based on the fair market value of rent that landlords lose.

On hand in the governor’s office for the signing was Rep. Devan Seabaugh, R-Marietta, the lead sponsor of the bill.

“Currently in Georgia law, we’re giving squatters tenant rights,” Seabaugh previously told State Affairs. “And my bill would take that away. It basically says, ‘You’re an intruder, you’re a criminal, and we’re going to treat you like a criminal.’ ”

Read these related stories:

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

State troopers are stretched to fight drugs and curb highway deaths

ATLANTA — When Cpl. Anthony Munoz straps on his bullet-proof vest each day and pulls out of the Department of Public Safety headquarters in Atlanta, Munoz never knows how his shift will unfold. What is for certain is that the traffic — of cars, criminals and contraband — is constant.

And what is also true is that there are not nearly enough state troopers on the road to catch them all.

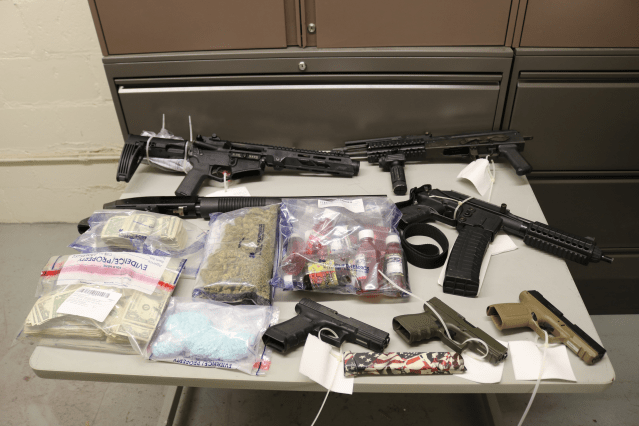

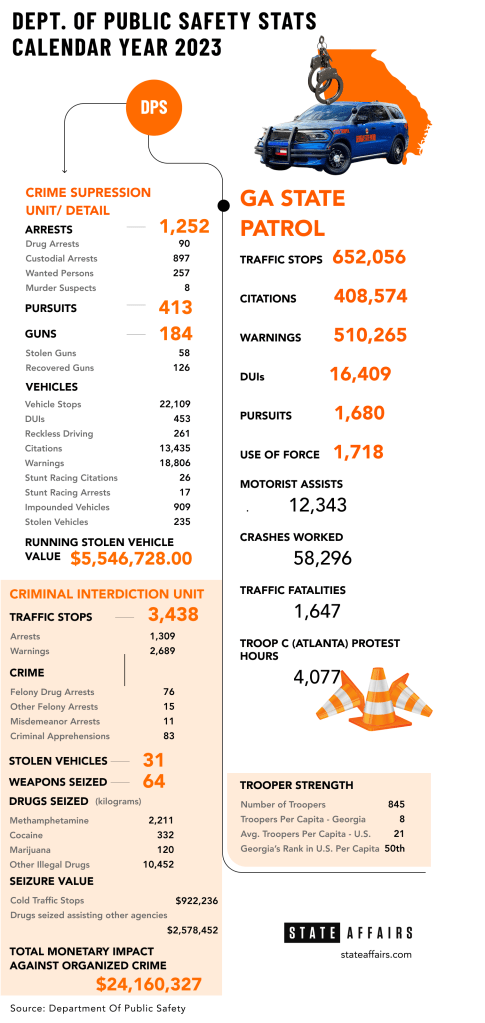

A 13-year veteran, trooper Munoz, 45, is part of the department’s Criminal Interdiction Unit, whose main focus is suppressing the robust illegal drug trade flowing through Georgia. Last year the eight-member team made 1,309 arrests, including 76 felony drug arrests, and helped other agencies seize $24 million worth of contraband.

In 2019, the unit had 25 members.

Capt. Greg Shackleford, the troop commander, said that in 2020 the unit was split up and half the team was sent to Georgia State Patrol posts around the state, which were hurting for staff, to conduct the Department of Public Safety’s core functions — traffic enforcement and responding to car crashes.

The split has translated into Munoz and the rest of his team now spending most of their time monitoring Interstate 20 just south of Atlanta, and Interstate 75/85 west of the city. He said they regularly support the investigations and busts of other local and federal agencies, and frequently join the governor’s crime suppression details, which have included taking down car thieves and street racers.

All this leaves his team with less time to develop intelligence on their own drug cases and to snare more traffickers. It also means the troopers no longer have time to monitor roads in rural areas in south Georgia where, Shackleford said, many drug traffickers driving trailers full of drugs and contraband enter the state on highways coming from Florida and Texas and now ride around unchecked for hundreds of miles.

Chronically understaffed

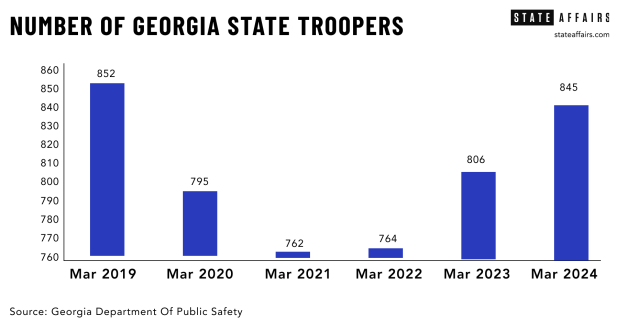

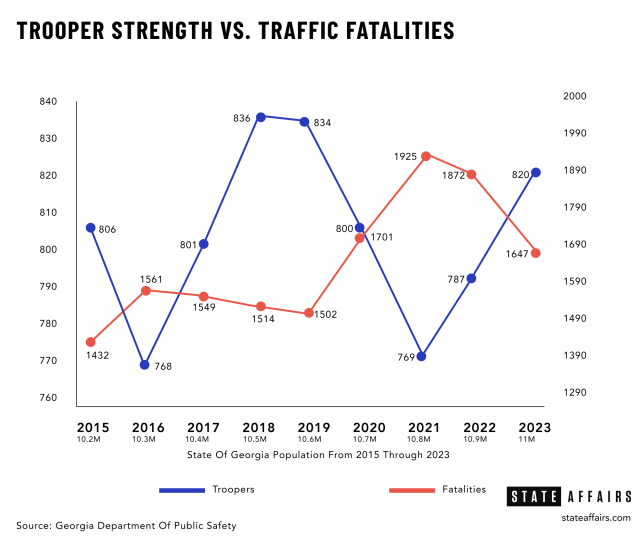

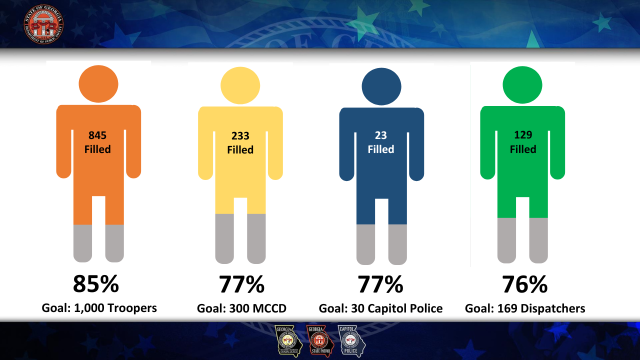

The Georgia State Patrol remains chronically understaffed. While the state’s population has grown, and with it the number of motorists, car crashes and criminal activity, the number of state troopers has hovered stubbornly between about 750 and 850 for over a decade, giving Georgia the unwanted distinction of having lowest number of troopers per capita in the country.

The average number of state troopers per capita in the U.S. is 21; for Georgia, it’s eight. And the outlook for changing that is not great, Col. William “Billy” Hitchens, the public safety commissioner, told legislators during hearings last fall — Unless the state makes bold moves in improving compensation. He said Georgia State Patrol has “aimed to reach 1,000 troopers for as long as I have been employed,” which is 30 years.

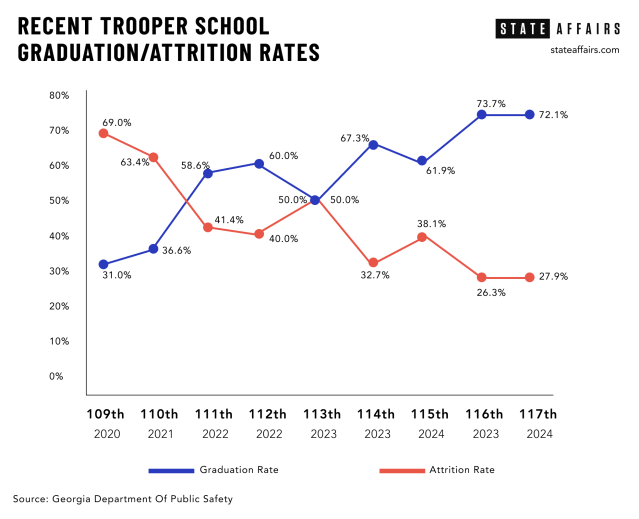

The state saw its trooper numbers plummet to 745 during the pandemic in 2021. The agency is now back to 845 troopers. The current trooper school started with 61 candidates, and if recent history is a guide, about 70% will graduate in September and put on the badge.

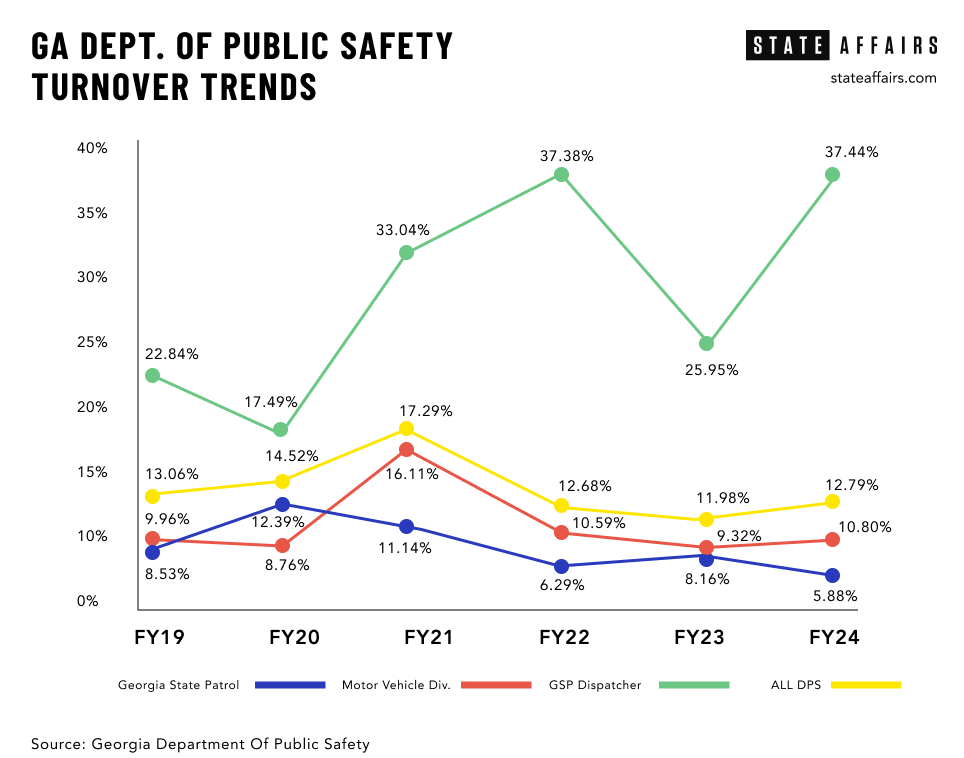

While “things are moving in the right direction” this year in terms of recruitment, said Hitchens, he said too many veteran officers are either resigning or retiring early.

Between 2018 and 2023, 48 troopers left the agency on a full-service retirement, meaning they had served for 30 years. During the same period, 341 troopers resigned, retired early or departed for other reasons. As it costs the department $153,397 to train a trooper, those who left early cost the state $52 million, said Lt. Col. Josh Lamb, director of administrative services for the Department of Public Safety.

Fewer troopers means more highway deaths

Fewer troopers on the state’s roads impact everyone, say law enforcement officials. .

“As our trooper strength decreases, traffic fatalities increase,” said Hitchens.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data shows a direct inverse relationship between trooper staffing and the number of fatalities in Georgia. At its low ebb in 2021, with 769 troopers, 1,925 people died on Georgia roads. More recently, in 2023, with 820 troopers, Georgia saw 1,647 fatalities, an 8% decrease over 2022.

“We are concerned with traffic patterns, the way people drive, and we enforce the law out there,” Hitchens told State Affairs. “When you start losing personnel, whether it’s the state, or cities and counties, one of the first things that may be taken away is traffic enforcement. Because they’re responding to other calls — robberies, domestics, you name it. And when troopers stop doing it, there are just fewer people out there reminding you, ‘Hey, that’s dangerous. Slow down.’ ”

The state patrol wrote 408,574 citations to motorists last year, but issued even more warnings — 510,265. Hitchens noted that mere trooper presence on the highway is a strong deterrent.

“It doesn’t have to be you that gets stopped,” he said. “Those 50 cars that ride by during that time and see that patrol car, go ‘Ooh, I don’t have my seatbelt on … I’m playing with my phone,’ and it just impacts that behavior. But the less officers you see on the road, the less you have people changing their driving behavior.”

Along with encouraging safer driving, DUI enforcement has become a higher priority for the department. A “Nighthawks” squad of 22 officers patrols after midnight in areas of the state where data analysis shows high incidences of alcohol and drug-induced crashes and violations. The state patrol made 16,409 arrests for driving under the influence in 2023.

Hitchens said the work of such special units is compromised when they’re pulled into other duties due to statewide manpower shortages. The three Nighthawks units, for example, are often pulled into other traffic stops and crime suppression details in Atlanta, Macon and Columbus. And drug interdiction officers have had to cover vehicle crashes and multiple public protests over the Atlanta Public Training Center (dubbed “Cop City”) and, more recently, conflict between Israelis and Palestinians in Gaza.

Besides securing troopers, Hitchens said the department is struggling to recruit dispatchers, who are the lifeline for troopers and officers who patrol alone and depend on dispatchers to provide critical information quickly. Today, the department has 129 dispatchers who work at nine regional call centers. They need 169 to be fully staffed.

A tough sell in the ‘Cop City’ era

Hitchens told lawmakers that heightened public criticism of law enforcement over the past few years has played a role in the department’s ongoing challenges to recruit and retain officers.

“People without understanding of what it’s like to be involved in a rapidly evolving life and death situation started scrutinizing officers, cities started defunding their police departments while demanding greater accountability and more training, both of which cost money,” he said. “Following the George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks and Breonna Taylor instances, the media and some leaders in our community nationwide began to demonize the police.”

Hitchens said that since the death of Manuel Teran, a protester against the planned Atlanta Police Training Center who was allegedly shot by a Georgia trooper during a firefight on the forested property in 2023, and the sometimes violent public demonstrations that ensued, “that dynamic just got worse. For a long time with ‘Cop City,’ it was constant protest, and you know, that weighs on you.”

Munoz, who was patrolling with other local law enforcement on the perimeter of the training center site the day Teran died, said the public’s jaundiced view of that episode and other recent struggles between police and citizens that have gone viral on social media can be frustrating.

“I know that a lot of the narrative out there is not true at all,” he said. “There are millions and millions of police encounters every day. And those [violent] ones are fractions of a percent of incidents, and whether a trooper or officer responds the right way, it all boils down to compliance. If you just comply, you’re presumed innocent, you’ll have your chance to make your case, and the facts will come out. Don’t argue, don’t fight, don’t resist. We don’t want to fight you.”

Noting that he has a wife and four children he wants to come home to, Munoz said, “We’ve been pounded with de-escalation in training, and that’s what we practice. I’m sure there are officers out there now that freeze and that say, ‘Do I do my job? Or am I going to be put in prison, because I reacted in a certain way?’ So we do carry that, and it’s a heavy, heavy burden.”

Last year three House Democrats introduced House Bill 107, the Police Accountability Act, which proposes an end to qualified immunity for law enforcement officers and would have required body-worn cameras for all peace officers. The bill did not advance out of committee, but Hitchens said taken together with the public unrest and anti-police sentiment since 2020, it all had a demoralizing effect on his officers.

“All of these factors are forcing officers to become fatigued with our profession,” he said. “They feel that support is ending and the job is not worth the risk.”

According to the Georgia Peace Officers Training and Standards (POST) Council, the number of officers with basic council certifications in Georgia dropped to 5,956 in 2023 from 6,666 in 2017.

“I don’t think there’s a single law enforcement agency in Georgia that is fully staffed,” said Chris Harvey, deputy executive director of Georgia POST. “And they have a very hard time getting qualified people on board. … There just aren’t enough quality people that are interested in doing this job.”

While some agencies have raised salaries and added signing bonuses, he said, “I can tell you that it’s not a solved problem. Because I don’t think it’s primarily a money issue. I think it has a lot to do with the difficulty of doing this job these days. I’m not sure it’s ever been harder to work in law enforcement. The amount of scrutiny along with the amount of violence that police officers encounter on a regular basis, they generally feel like they’re out there alone. If they make one mistake, they’re gonna pay dearly for it. … It’s a tough sell.”

Father and son patrol leaders fight for trooper compensation

For Hitchens, his push to recruit potential state troopers and convince state leaders to increase pay and benefits for troopers is supported by an unlikely suspect — his dad.

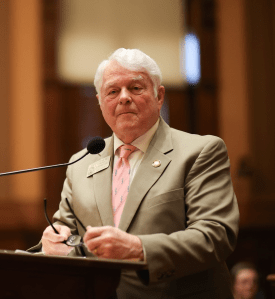

House Appropriations public safety subcommittee chair Rep. Bill Hitchens, R- Rincon is a former trooper who served in the Georgia State Patrol for 28 years, and was later appointed by former Gov. Sonny Perdue to serve as public safety commissioner from 2004 to 2011. The elder Hitchens has served in the House since 2013.

At the House Working Group on Public Safety meeting last fall, Rep. Hitchens noted that the state patrol has maintained around 700 troopers since he joined in 1969, when the state population was about 4 million. “Now it’s 11 million people … and we have a lot more murders, stolen cars and merchandise,” the elder Hitchens said. “Where we fell down, I don’t know. It’s just we’ve never grown. … And now we’re at a breaking point.”

The younger Hitchens was appointed by Gov. Brian Kemp as deputy commissioner for public safety in 2020, and then as commissioner in 2023. As commissioner he oversees the Georgia State Patrol, the Motor Carrier Compliance Division, the Capitol Police Division, and other special law enforcement units, including the crime suppression, SWAT and canine teams.

The son and father team have successfully fought for substantial pay raises for troopers, whose salaries have increased over the past three legislative cycles by nearly $17,000. That includes a 4% cost of living increase and a $3,000 bonus for law enforcement officers approved by the General Assembly in the fiscal year 2025 budget. The starting salary for a new trooper will be $63,684 as of July 1, if the governor approves it in the budget, as expected.

Dispatchers will also get a boost in next year’s budget, with new pay step increases that can take them from a starting salary of $39,000 to up to $56,000 as they earn promotions.

Col. Hitchens said those pay bumps seem to be turning the tide on recruitment. The number of applicants and graduates rose for the last few trooper schools held over the past year. Other changes the department made to trooper school requirements have also helped, including allowing people to go home more often during training, permitting access to mobile phones at night, and allowing people with arm tattoos to train and serve, if they cover them with long sleeves.

“We tried to make changes in training that we felt like really didn’t help people stay,” said Hitchens. “And we didn’t make it kinder or gentler. I mean, in this job that you sign up for, there’s got to be a certain level of discipline, there’s got to be a certain level of respect, with high physical training standards, that’s still there. But the things that we could change, we decided to do.”

Both men remain concerned about how to stem the trend of early retirement, and agree that sweetening the retirement package is the key way to combat it.

Currently most troopers qualify for a pension equal to 1% of their final pay for every year of service, and can also participate in a 401(K) savings plan while they serve, which the state matches up to 9%, depending on their number of years on the force. But Col. Hitchens is pushing for a more generous “defined benefit” retirement plan, with a 3% pension, which he said would double what most troopers get when they retire. Instead of earning about $25,000 a year on average, they would receive about $52,000.

Presently, the average tenure of a state trooper is 10 years, nowhere close to the 30-year careers Hitchens and other leaders want his officers to pursue.

And he knows it matters to them, as retirement benefits emerged as the number one retention issue on a recent agency-wide, anonymous survey.

“Every other agency is increasing their hiring packages, raising pay and offering better benefits, from retirement to free health care,” Hitchens said, noting that the Atlanta and Sandy Springs police departments offer substantially higher pay and 3% defined benefit plans.

“We’re in a competitive bidding process, and we have to offer a reward that’s worth the risk our people are taking with their lives and liberty.”

The tenure of senior officers also matters because of the crucial role they play in mentoring new recruits.

“When we have our young troopers, the men and women that come into the field, they’re excited,” said Shackleford, the troop commander, who spent much of his 36-year public safety career in SWAT before taking over Troop K, which includes the crime suppression, criminal interdiction, K-9, SWAT and dive units. “They see the fast cars, they want to get into something. And the problem is, it’s just like a puppy. A puppy’s gonna get into something and make a mess. So we need the older ones to kind of calm them down and guide them a bit, show them how to see and assess a situation.”

Such role modeling of behavior, said Hitchens, “is very important, especially with de-escalation. A senior officer, having dealt with so much of that, has that confidence and the competence to carry out [their] job in a way that I think a lot of younger, less experienced officers don’t have yet. And that’s how you learn and morph over a career,” said Hitchens, adding that that transfer of knowledge and practice from veterans to recruits “benefits the public as well.”

Rep. Hitchens co-sponsored two bills related to bolstering retirement plans for law enforcement that passed out of the retirement committee during the last session. One passed in the House, but did not get a vote in the Senate. Other lawmakers balked at the cost.

Read these related stories:

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs