Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoGeorgia’s aging school buses, bus driver shortage lead to missed classes, meals and safety issues

Students unload from buses at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens on April 11, 2023. Teachers in Georgia say many schools have reduced or canceled field trips due to mechanical issues with buses and the bus driver shortage. (Credit: Jill Jordan Seider)

This story is part one of an ongoing investigation that looks at the state’s aging school buses, bus driver shortages and a decline in state funding of student transportation — a trifecta that is having a significant impact on the education of Georgia’s youth. Part two focuses on the funding issues and potential solutions. Read it here.

Zhaqueline Stewart, an 18-year-old senior at Westside High School in Richmond County, is saving up to study nursing at Augusta University by waiting tables at Waffle House after school.

But Stewart, a B-minus student, is worried she might not have enough credits to graduate. She’s been late to school so many times over the past two years, due to the late arrival of her school bus, that she said it has affected her grades.

Last year, she failed geometry, her first-period class. Stewart said her bus, scheduled to arrive at her stop at 6:30 a.m., routinely arrived 30 minutes late. On some days, the bus would break down on the way to school and Stewart and her classmates had to wait on the side of the road for a mechanic or another bus to arrive.

In either scenario, they’d get to school too late for the free breakfast. She’d rush to her math class, “and the important stuff, the instruction part, would be over,” she said. Then she’d feel progressively “tired and grouchy” as the day wore on. “Because, you know, I haven’t eaten anything, and then our lunch is like halfway through the school day.”

Yolanda Brown is Stewart’s regular bus driver, and president of the Transport Workers’ Union Local 239 in Augusta. A 14-year driver for Richmond County Schools, she said many of the buses in the fleet are old, and break down mid-route or require repairs that take them out of service, “all day, every day.” That ranges from engine and transmission problems, to alternators, to overheating radiators, she said. “You get that fixed, and now the stop sign doesn’t work, or a headlight goes out. It’s just one thing after another.”

The breakdowns of the aging school bus fleet — 67 of Richmond County’s 215 buses are 15 or more years old — are compounded by a shortage of bus drivers. Brown said their school system is currently short 40 to 50 drivers, and that the drivers they do have must take on additional staggered, combined routes to get students to and from school. The extra time that takes is making some students late to school every day, she said.

“And they can’t keep drivers on staff because they’re not paying us enough,” said Brown, who earns $16 an hour. The hourly pay for bus drivers in Richmond starts at $13.86 and caps at $18.19, she said. And even after driving for 20 or 30 years, most drivers will earn a state pension of less than $500 per month. Though the school district is offering drivers extra financial incentives for perfect attendance and for referring new drivers, and free commercial driver’s license (CDL) training to new job applicants, “it’s still not a livable wage,” Brown said.

“People are getting their CDLs, driving for a year or so, then going somewhere else,” said Brown. “They can drive a dump truck, a tour bus, do long-distance hauling — just about anything else pays better than this.”

What’s happening in Richmond County is not unique. The dual challenges posed by aging school bus fleets and the chronic shortage of bus drivers — and bus mechanics, and other transportation personnel — are having a negative impact on student transportation systems in school districts across the state, in both urban and rural areas.

A three-month investigation by State Affairs reveals that in some districts, the school transportation system problems are so severe they’re causing not only longer, crowded bus rides and tardiness for students, but safety issues on some buses and a drop in student achievement at some schools.

Click here to register for our town hall on the school bus crisis.

Aging bus fleets

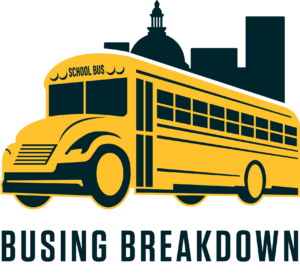

According to the Department of Education (DOE), 23% of Georgia’s 15,561 daily route buses are at least 15 years old, the age at which buses are generally considered “beyond their useful life,” and present diminishing returns on investments by school districts to repair and maintain them. Most school districts also have a number of past-their-prime buses they keep in inventory as “spares,” to be used for field trips, school activities, and to sub in for regular route buses as needed.

An analysis of DOE bus data for each of the state’s 180 school districts in 2022 shows wide variation in terms of fleet ages. Some districts have upgraded their fleets, acquiring dozens of new gas-, propane- and even electric-powered buses over the last five to 10 years, while other districts are operating primarily older, diesel-powered buses, where 40% to 50% of the buses they use each day are 15 to 20 years old.

Interviews with bus drivers, mechanics, transportation directors and school officials in the districts with older fleets indicate that many are using their spare buses on a daily basis, due to the mechanical issues plaguing their regular fleets. When spare buses are included, State Affairs finds that 32% of all school buses statewide, or 6,232 of 19,762 buses, are 15 or more years old.

Capt. Clint Durrence leads the School Bus Safety Unit of the Motor Carrier Compliance Division for the Department of Public Safety (DPS), which annually inspects all of the state’s school buses. He said that over the past five years, on average, about 25% of buses inspected were found to have “out of service (OOS) defects,” or mechanical problems posing safety risks that must be fixed before the bus can be permitted for use.

In 2022, DPS data shows that 12% of all school buses were grounded after either their annual or spot inspections by DPS. For 22 districts, the OOS defect rate ranged from 20% to 32%. That included Atlanta Public Schools, where 160 out of 576 buses inspected had problems with air brakes, tires and wheels, stop arms and crossing gates, fuel leaks and exhaust systems. Overall, common component failures included brakes, crossing gates, tie rods, drive shafts, tires and wheels, shocks, lights, child reminder switches, and exhaust systems.

Durrence said mechanical problems crop up “sometimes because the fleet is old, and in some cases the school systems don’t have a big budget for mechanics and transportation maintenance.”

Besides breaking down more often, older buses with diesel engines produce exhaust fumes with high levels of pollution that are unhealthy for students, including cancer-causing solids or liquid droplets that when inhaled can be dangerous. A 2019 study by Georgia State University showed that when 2,600 diesel-powered school buses in Georgia were retrofitted with diesel exhaust-filtering devices (at $8,000 apiece), both the respiratory health and academic performance of the students riding them significantly improved.

Many bus models older than 2007 lack safety features now standard on newer buses, such as a “child check” bus alarm, which requires drivers to walk down the aisle and push a button at the rear of the bus before turning off the engine, and electronic stability control technology, which alerts drivers to brake or make a steering adjustment (or automatically does it for them) to avoid collisions and rollovers, and to adjust to adverse road conditions.

Most older buses also don’t have air conditioning, which can make things unpleasant for students and drivers when temperatures exceed 80 degrees. And because air conditioning is an expensive add-on, costing as much as $10,000 on top of the standard price of $100,000 for today’s buses, some districts still don’t opt for it to save on costs. Those that add air conditioning, video cameras, illuminated stop arms and other modern safety features can buy fewer new buses with the $88,110 per bus that the state currently allots to districts for bus replacement.

Drop in state funding

The key factor driving the age and condition of bus fleets in Georgia, as well as the pay and benefits local districts can offer to drivers, mechanics and other personnel, is, of course, funding.

Historically, the cost of student transportation in Georgia, as with all of K-12 public education, has been split primarily between the state and local school districts, with a small portion provided by the federal government. Through the early 1990s, the state covered about half the cost of transporting students. But since then, as school districts’ transportation costs have steadily increased, along with enrollment growth at schools, rising fuel prices and labor costs, the state’s investment in this educational expense category has remained fairly flat.

In 2002, the state covered $178 million, or 40%, of the total $444 million cost of student transportation. Twenty years later, in 2022, the state allocated $232 million to school districts, representing only 20% of the $1.1 billion total cost of student transportation. The state has been covering 15% to 20% of the total transportation cost over the past 10 years, thus shifting most of the financial responsibility to local school districts.

Notably, also in 2022 following Gov. Brian Kemp’s recommendation, the transportation appropriation included the first $63 million of a three-year, $188 million allotment for replacement buses and incentives for districts to purchase more energy-efficient buses. This infusion of capital funding will allow some school districts to collectively purchase 582 new buses each year through 2024, which will reduce by about a third the overall number of older buses in Georgia exceeding their useful life that are still in operation.

Bus driver shortage and safety concerns

And then there is the issue of bus drivers. Georgia’s local school districts find themselves in the throes of a severe bus driver and transportation personnel shortage that is both local and national.

“Drivers are a precious commodity,” said Cornelius Ball, a 10-year school board member in rural Turner County. He said his district has all but two of its 22 routes covered, but no backup drivers. To cover the vacant routes and daily absences, Turner uses teachers, coaches and school resource officers to drive. “And when you have those types of personnel driving buses, it’s not just inconvenient to pull them away from their regular role, but operationally, your school resource officers really need to be protecting the school.”

In Oconee County, bus driver Julianne Radford, 55, said drivers are beginning to “make a stink” about low pay and short-staffing. In March, her husband Terry Radford appeared at an Oconee school board meeting to demand better pay on behalf of a dozen district drivers. The pay scale in Oconee is $17 to $20 an hour, she said, well below what drivers are paid in other districts, such as Gwinnett, where the range is $19 to $27 an hour. As a result, she said, “Drivers are quitting and going to other districts, and we also just lost our senior mechanic.”

Radford said because they are short several drivers, Oconee’s one remaining mechanic and other transportation staff are regularly driving buses. Last month, when a school bus was hit by a car, the transportation director was “out on a bus. So there was no one available to respond to the accident, except the police.”

Lisa Morgan, president of the Georgia Association of Educators, said, “As state funding decreases, the pressure on local districts to fund the salaries and benefits of bus drivers and other employees increases. So that has kept the wages and benefits down, which has made it harder to recruit people to work as school bus drivers, given that there’s a bus driver shortage statewide, and the marketplace is already very tough.”

In their responses to the DOE’s annual transportation survey of school superintendents in 2022, more than a dozen reported that they had to forgo their annual bus driver skills evaluations due to transportation staffing shortages.

In Tattnall County, the survey response said, simply: “We are all having to drive. Unable to do it.”

In Houston County, the reason given was “staffing shortages and amount of time coordinators/evaluators are driving routes.”

Other districts also reported not doing bus evacuation drills, employee evaluations, and suspending legally mandated “safe student riding” classes due to lack of personnel.

“That absolutely is concerning. I don’t know how prevalent that is, but even if it’s happening in just one system, it’s concerning,” said DOE Director of Pupil Transportation Mike Sanders, when asked about the safety procedures some districts were skipping in an interview with State Affairs last month.

Sanders said the bus driver shortage, which is “worse than it’s ever been,” has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused many bus drivers, concerned over health risks, to quit or retire. Bus driving is a part-time job or a second career for many drivers, he said, and “historically, our drivers tend to be older — into their 60s and 70s.”

Pre-pandemic, the average age of a bus driver in Georgia was 54, he said. Now, DOE transportation staff are trying to help districts find ways to address the driver shortage, in part by recruiting younger drivers.

“There is no silver bullet,” said Sanders. “Every district is different … some might find that offering [drivers] six or eight hours a day instead of four hours will help … Other drivers aren’t as concerned about pay as they are about air conditioning.”

DOE pupil transportation consultant Ken Johnson, who works with school districts in the metro Atlanta area and northwest Georgia, said illegal drug use is also a problem among new and would-be recruits.

“A lot of our workforce, unfortunately, is using products they shouldn’t use, and we do preemployment drug testing and random drug testing, and that does take [out] a pretty big chunk of people who might be interested in driving a bus,” he said, adding that illegal substances they commonly find in test results range from opioids to CBD oil.

Overcrowded buses and a call for bus monitors

In Fulton County, one of the largest school transportation systems in the state, transporting 45,000 students on 750 daily routes, bus drivers are pleading with the school board to raise salaries and to fill more than 150 vacant driver positions to ease their workload. For some, it’s a safety issue as much as a financial concern.

Fulton bus driver Evelyn Fields, who spoke on behalf of herself and 80 other drivers to the Fulton school board last year, said she regularly drives double and triple routes, which in Fulton means combining students from two or three different routes onto one bus. The result, she said, is buses that are overcrowded, students often sitting three to a seat, with their legs in the aisles, and many times standing in the aisles.

“If a car jumps in front of my bus, and I have to step on the brakes, they’re going to come flying to the front,” said Fields, who is concerned about both physical injuries to students, and “what this does to their state of mind. They’re anxious, and frustrated, and that can lead to a bad situation for everyone.”

The overcrowding causes tension and tempers to flare among students, and leads to behavioral issues on buses, said Fields. She numbers among drivers and students in Fulton who are asking the district, and the state, to supply more funding for not only bus drivers, but for bus monitors, which they say would help to curb the fighting and bullying that is now commonplace on buses.

Fulton County bus driver Evelyn Fields says the driver shortage has led to overcrowding and unsafe conditions for students on some buses. (Credit: Jill Jordan Sieder)

“I love my students, and I value my job, but this constant overload and stress is not what I signed up for,” said Fields, who is 41 and has been driving buses for Fulton for seven years. “I’m getting burned out and tired and drained, and I can’t function when I get home to help my children out with their homework or projects.”

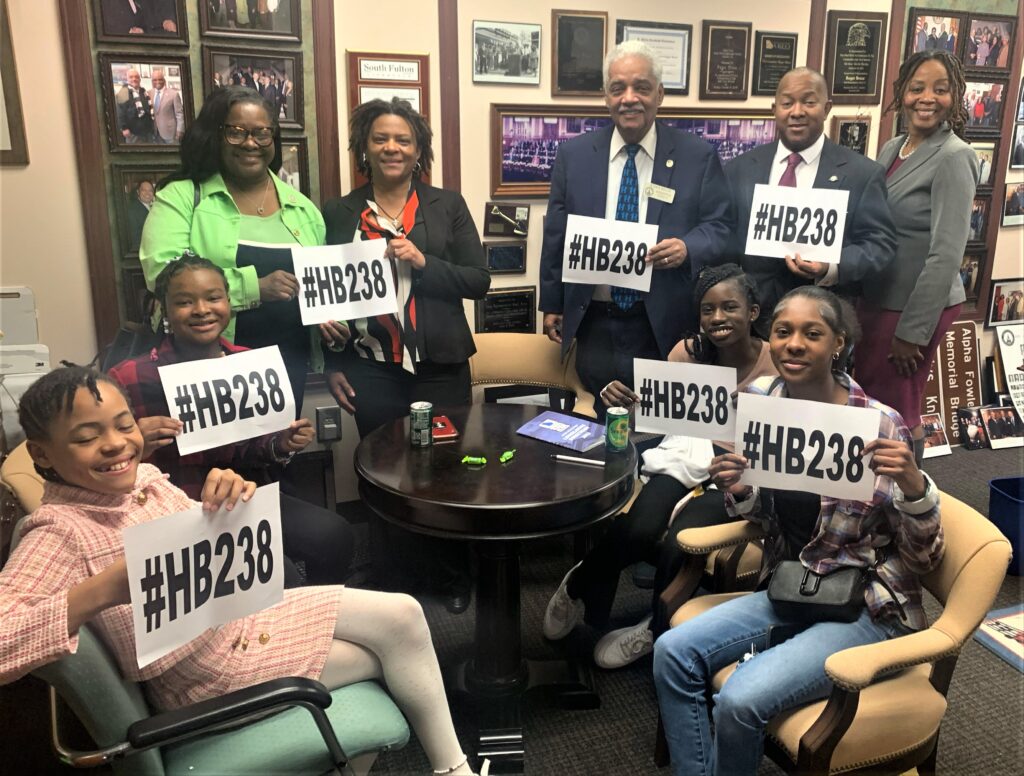

In March, four students from Renaissance Middle School in south Fulton testified before the House Education Policy subcommittee on behalf of HB 238, a bill they helped to draft with Rep. Roger Bruce, D-Atlanta, which would create a program to fund grants to local districts for bus monitors “to enhance student safety.”

The students told legislators about incidents of fighting on overcrowded buses, and said students often sit in each other’s laps and stand in the aisles while the bus is moving.

“This bill would make the environment for students and bus drivers more safe,” said

Kai Leite, a sixth grader. “Almost every day, the bus driver has to scold students, and she’s looking back at us in the rearview mirror, and we’re screaming, ‘Hey! Look at the road!’”

The bus monitor bill, taken up late in the session, did not move. But legislators on the Education Policy subcommittee seemed concerned about what the students shared. (So did Gov. Brian Kemp, whom the students paid a visit to in March).

“Kids can’t learn if they’re worried about getting to school,” said Rep. David Wilkerson, D-Locust Grove.

Rep. Mesha Mainor, D-Atlanta, said the overcrowded conditions on the buses “seem like a liability,” and noted that “Brown v. Board of Education [said] “we must provide kids with an adequate education. Part of adequate education is transportation…Once those kids enter the bus, they’ve entered the educational system…This is a civil rights violation, because we are not providing an adequate education.”

And Rep. Lauren Daniel, R-Locust Grove, said, “My biggest concern is they’re having to sit on laps. That’s inappropriate, if that’s a recurring thing…We need to ask, why are the buses overcrowded? I do believe it’s a statewide issue… In my district, kids are not getting home until 7 or 8 o’clock, and buses are having to take multiple trips.”

Impact on student achievement and well-being

Teachers, parents and students told State Affairs that the chronic lateness of buses is having a negative impact on student achievement.

Two Henry County high school teachers said buses typically arrive 30 minutes to an hour late, causing students at their school to miss breakfast, and some or all of their first-period classes. The school has created a 40-minute “instructional focus” period on Wednesdays for those students to catch up on lessons they missed. But a science teacher, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said “that’s too little, too late for most of them” and that failure rates among students in first-period classes, including “math, English, history and all of the CTAE [Career, Technical and Agricultural Education] courses” have significantly increased as a result.

Myia Sutton, who works from home as a tech consultant, said her 15-year-old daughter’s bus is supposed to get her home from Luella Middle School in Henry County around 5 o’clock each day, but often arrives an hour or more later, due to combined bus routes. “I’m watching the bus on the school tracking app, and I can see she’s 2 or 3 miles away, but the bus just keeps going further away.”

Sutton said when her daughter, Jas, finally gets home from her long ride, “she’s frazzled, she’s having to rush to do her homework, eat dinner; she doesn’t really get to unwind from the day. She takes school seriously, and I can see that this creates anxiety for her.”

Senior Kalei James, who attends technology-focused Seckinger High School in Gwinnett County, said she has been late to her Foundations of Artificial Intelligence class multiple times this year, including one day when a substitute driver showed up in an older bus, “and the bus doors wouldn’t open, and we couldn’t get on, so the bus just left us,” she said. “It’s very frustrating when bus issues jeopardize the time I could have spent learning.”

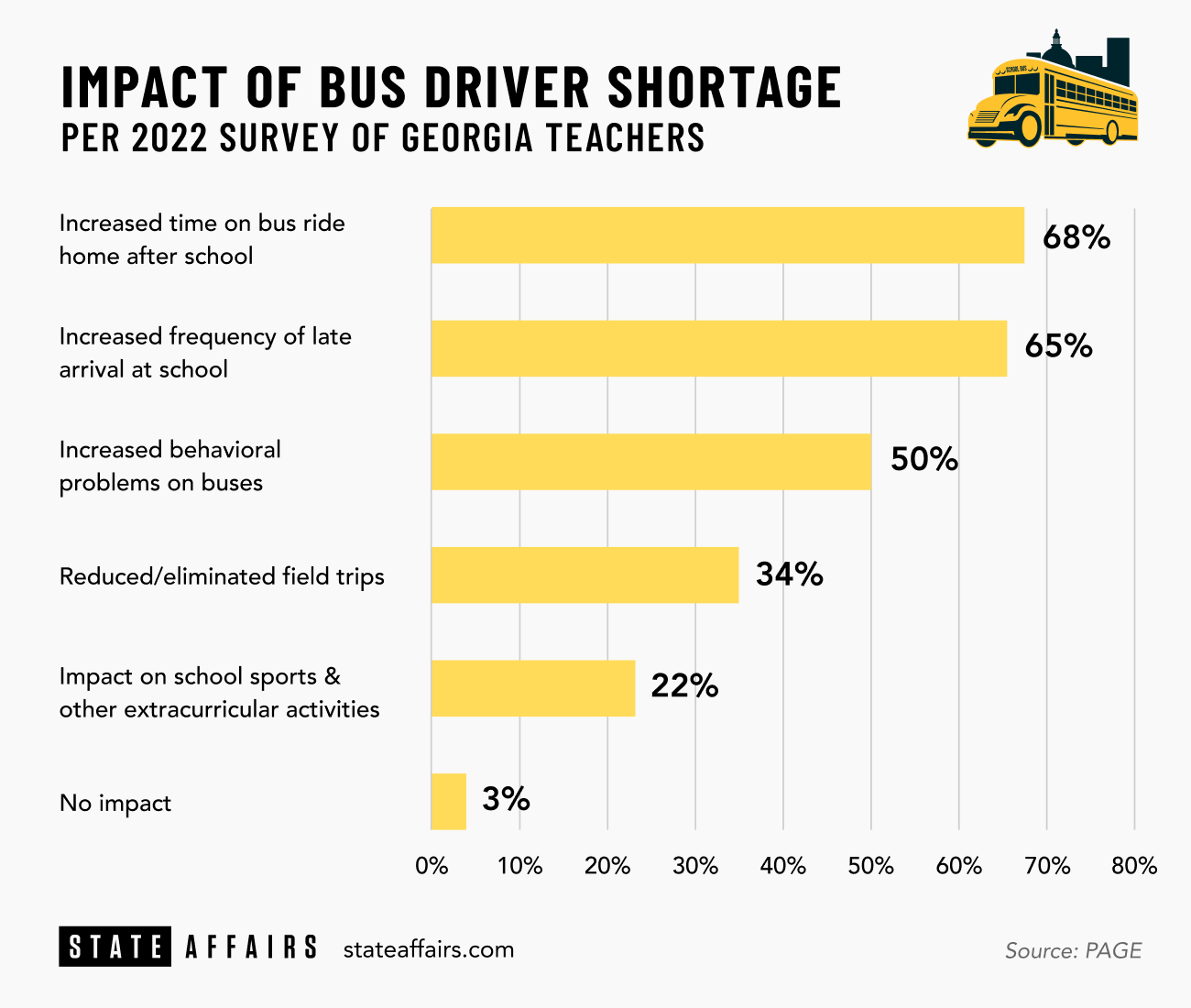

(Design by Brittney Phan for State Affairs)

In a 2022 survey conducted by the Professional Association of Georgia Educators, the majority of 2,423 teachers surveyed said the bus driver shortage is causing an increased frequency of students arriving late to and from school, and 50% said it’s causing more behavioral problems on buses. About a third said field trips at schools are being reduced or eliminated due to bus problems.

“That kind of breaks my heart to hear that kids are not getting breakfast or missing class because the bus was late,” said Ball, who is a district director of the Georgia School Boards Association (GSBA). “That means we didn’t do our jobs as a governance team. That’s state legislators, the school boards, even our congressmen. Somewhere we have failed these kids by not making sure that they get to school on time. And we read now the state of Georgia has more revenue than we’ve ever had. We’ve clearly got to switch our priorities and fund transportation at a rate that doesn’t penalize children.”

Read these related stories:

Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @JOURNALISTAJILL or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Busing Breakdown Logo (Credit: Brittney Phan)

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …