Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoGeorgia’s struggling school bus system: Finding funds and drivers

A seasoned school bus in Taliaferro County, Georgia, on May 4, 2023. (Credit: Taliaferro County Schools)

This story is part two of an ongoing investigation that looks at the state’s aging school buses, bus driver shortages and a decline in state funding for student transportation — a trifecta that is having a serious impact on the education of a significant portion of Georgia’s youth. Part one focuses on the ways these challenges are affecting students and transportation personnel. Read it here.

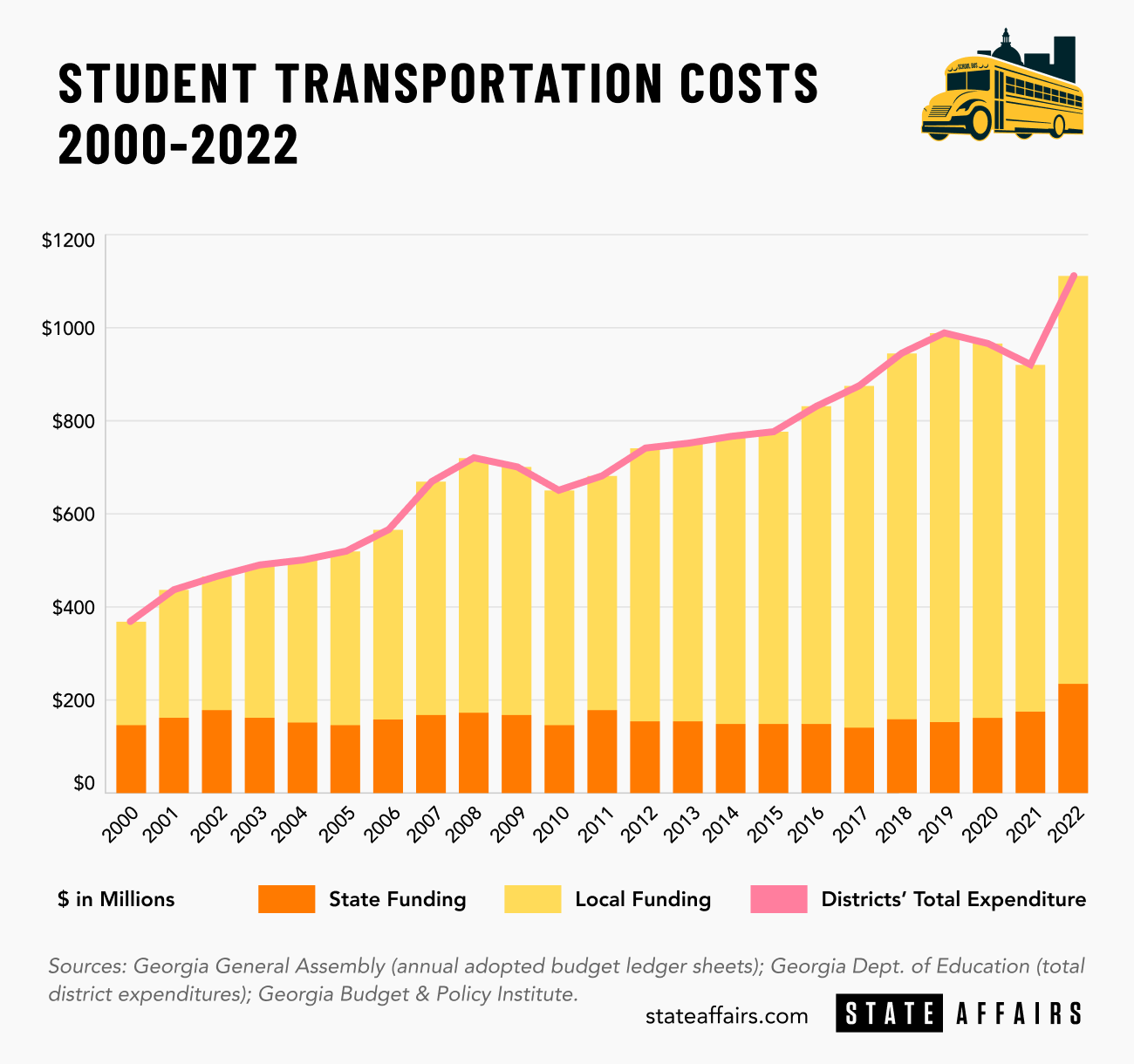

Over the past 30 years, as Georgia’s population has grown, public schools in most districts have seen increased enrollment, fuel prices have risen, and labor costs have soared. The state’s student transportation budget has expanded, too, tripling in size.

In the early 1990s, the state covered about half the cost of transporting the state’s children to and from public schools. Since then, the state’s share of this expense has steadily declined, and local school districts have had to pay for most of those costs. Because some lower-wealth districts can’t generate enough funds, they’ve struggled to replace older buses with new ones and to maintain bus fleets in good working order.

Now, in a time of record-high inflation, supply chain challenges, and an ever-worsening labor shortage, more school districts across the state are finding it difficult to hire and retain bus drivers, mechanics and other transportation personnel to upgrade their fleets and to provide reliable bus service for students. Buses are breaking down more frequently in some districts, and students in others find themselves crammed into crowded buses and not always getting to school on time.

So, whose responsibility is it to ensure that schools have decent buses, adequate transportation staffing, and sufficient funding to maintain safe and reliable bus operations?

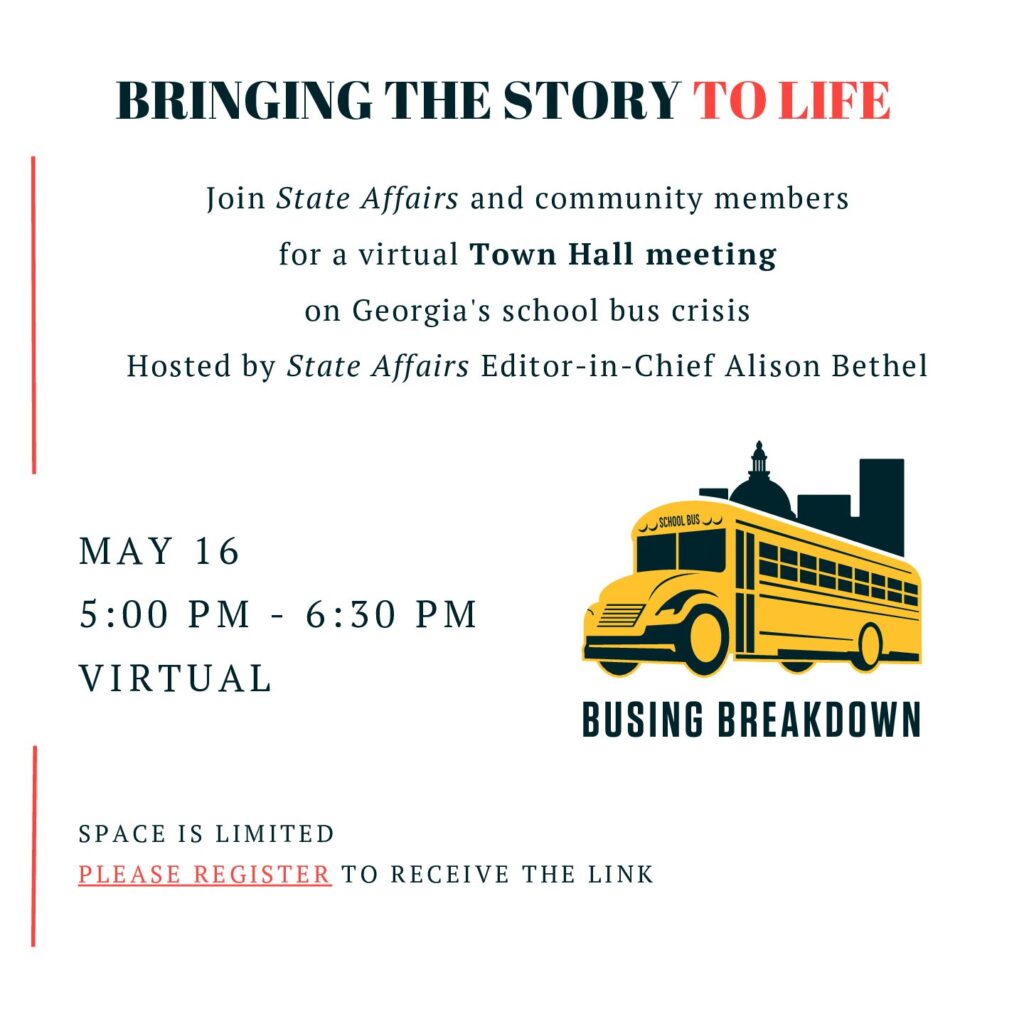

Click here to register for our town hall on the school bus crisis.

By law, the state is required to help local school districts transport public school students who live at least 1.5 miles away from their assigned school, as well as students with special needs.

“But there is no minimum amount that the state is required to contribute to this mandated service,” said Claire Suggs, legislative policy analyst for Professional Association of Georgia Educators. “There should be, because we have to have kids in school.”

In 2012, a joint legislative Education Finance Study Commission that spent 15 months looking at K-12 school funding recommended the state substantially increase bond funding for school bus replacement to $45 million per year “to keep the fleet of buses operated by school systems current and operating within their useful life cycle.” The commission also recommended the state fund half the total cost of student transportation, as calculated by the Department of Education.

But the state’s share of student transportation costs has hovered between 15% and 20% since then. In 2022, the state allocated $232 million to school districts, representing 20.3% of the $1.1 billion total cost of student transportation.

Local school districts try to fill that funding gap through local fundraising efforts. The most common approach that counties take is to raise millage rates on property taxes. The millage, or tax rate, is set in each county by the board of county commissioners and the Board of Education, according to the Georgia Department of Revenue. One millage equals a tax liability of $1 per $1,000 of assessed value.

Barrow County Schools had a millage rate of 17.881 mills in 2022, a 12% increase over 2021, which was projected to yield $42 million and cost taxpayers with a home value of $300,000 about $227. In Henry County, the school system’s taxation rate of 20 mills will yield $207 million in taxes in 2023, a bit more than in 2022 because property values have increased.

“But counties have a constitutional limit — they can only levy up to 20 mills,” said Angela Palm, legislative and policy director of the Georgia School Boards Association. “Districts get to a place where they can’t go any further, and the only thing they can do is cut from other school programs to maintain transportation.”

School districts can also raise education funds through Education Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax (ESPLOST) campaigns, using a one-penny sales tax, if approved by local residents, dedicated to capital projects such as buildings, equipment and vehicles. ESPLOST money cannot be used for personnel costs.

In Lumpkin County, a mountainous area in north Georgia that includes Dahlonega, school Superintendent Rob Brown said his district had been allotted one or two buses a year from the state for the last five years. “And we’ve got many miles of dirt roads that are hard on buses, and we couldn’t keep up with repairs on our aging fleet,” he said.

So in 2022, Lumpkin purchased 20 buses at one time, using $2 million in ESPLOST funds.

Their new gas-powered buses, which cost about $100,000 each, have up-to-date features the old buses don’t, including air conditioning, electronic stability control, better radios and video cameras and an illuminated stop arm.

Brown said he’s grateful that his district, which enjoys a good deal of tourism business, could generate the needed funds. But he noted that “poorer rural areas” with a smaller property tax base and a limited amount of commerce, such as Jeff Davis County Schools in south Georgia where he previously worked, “are hard-pressed to get much out of either a millage increase or an ESPLOST,” he said.

“The value of a mill in Jeff Davis is about $200,000; that doesn’t get you very far,” said Brown. “And even if they could do an ESPLOST, you can’t use it to pay bus drivers and mechanics.”

In rural districts, Brown said, “if they’ve got inoperable buses and not enough drivers, they’ll have to keep doubling up on routes and packing those buses three to a seat. Routes that might usually take an hour and 15 minutes might take two hours and 15 minutes, which is hard on students. And of course, you’re putting more pressure on your team by doing that. They can get overwhelmed.”

“The ESPLOST is fantastic for high-wealth school districts, but that well is dry for low wealth and rural districts,” said Stephen Owens, education director of the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI).

In Taliaferro County, “We’ve got three convenience stores and a couple of restaurants,” said school Superintendent Allen Fort. “Our monthly SPLOST generates $12,000. We’ve used it for a bus, school equipment and technology upgrades we really needed. And we’re at 17.9 mills now — we raise $50,000 per mill, so it costs us 2 mills to buy a bus. We have no ability to fund all of the buses we need to keep our fleet updated.”

Clayton County Public Schools currently operates 497 diesel buses, 300 of which are “past their life span,” said Denise Hall, the transportation director for Clayton. She said those buses “have frequent mechanical issues and are in constant need of repair.” She added that they often break down en route, forcing her transportation office to respond with tow trucks, mechanics or a spare bus and backup driver.

A $350 million ESPLOST passed in April will allow Clayton to invest $29 million in purchasing 300 new buses over the next several years. Clayton has also won a federal Clean Air grant of $9.8 million to purchase 25 electric buses and build two charging stations.

But Hall is still challenged to find drivers for her new buses.

“Drivers are pretty much a revolving door,” said Hall. “For every one I hire, two have to terminate. I was 50 drivers short at the start of the school year. Now I have seven open routes.” She said, “Because turnover is so rapid, we do [commercial driver’s license ] classes every two weeks to make ourselves whole.” Despite raising starting pay to $21 per hour from $18 last fall and offering retention bonuses, “some people come in just to get the Class B license and go straight to Amazon.”

Rep. Matt Hatchett, R-Dublin, the House Appropriations Committee chair, said the bus driver shortage in Georgia “is in line with the labor shortage nationally — every job you can think of is experiencing a shortage in labor.” He said he was unaware of problems with aging fleets or the impact of busing conditions on students. Accounts of those challenges, he added, are troubling.

“I do know that many districts are depending on the state’s funding, different ones at different levels,” he said. “Some tax their local property owners a lot less millage than others. I mean, where is that magic place that they all need to be, and who’s funding what? What is the local district paying? You know, what millage are they at? Are they at 20 mills? At 10? At 7?”

Hatchett noted that “the governor funded $188 million in new school buses last year” and that the Legislature “put more money in education this year than we ever have, $13.1 billion. I mean, we’re fully funding QBE [the Quality Basic Education funding formula for K-12 schools]. Teachers got another $2,000. And bus drivers got a 5% raise. And so we can look at the bad things, but the good things are that education is a focus of our governor, our Senate, our House.”

Hatchett said he has not spent much time considering student transportation in the budget. “And you’re pointing out an area that we need to look at, and we need to address,” he said. “We’ve got to get transportation where it needs to be. But we also need to go district by district, and see what’s being paid for. Due to a lot of federal funds from COVID [relief], they’ve got a lot of money … Are they spending the education funds they have on buses, or on athletics? Or in the classroom? You know, what are we missing?”

Owens of GBPI said the state’s 2022 appropriation for buses “is a wonderful and welcome investment, and I hope it’s a sign of more to come.” But, he noted, because pupil transportation is a separate education budget expense category not integrated into the QBE funding formula, “lawmakers can continue to spend the same amount on transportation year after year, and rightfully say that they fully funded QBE. But what they’re funding does not come close to covering the true cost of transportation.”

“A 5% raise on $18 an hour for bus drivers does not address the financial needs of transportation personnel,” Owens said. “They need a livable wage, and more than a meager pension. They are viewed as a valued part of the educational system by their schools and their communities, but they are not treated that way in the budget.”

Regarding schools’ use of federal funds, the Georgia Partnership for Excellence in Education released a DOE-commissioned study report in November that showed Georgia’s school districts and state commission charter schools (also known as local education agencies, or LEAs) have used COVID-19 relief and emergency relief funds to cover student transportation costs.

Nearly 31% of participating LEAs reported using Elementary and Secondary Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds to offset fuel costs, and 22% spent the federal funds on other student transportation costs, including replacing old buses.

Owens noted that the fuel costs are “going to be there when the federal money is gone. And so that almost feels like that strengthens that idea that we need to have consistent state support, so we don’t rely on a one-time federal infusion of cash.”

“The state needs to vastly increase its commitment to transportation, and to start by taking a holistic look at the education budget and the QBE funding formula,” Palm, from the Georgia School Boards Association, said. “And a partnership between local school districts and the state to support student transportation needs to be more evenly split than it currently is. I don’t know if that’s 50-50 or 60-40, but I don’t think it should be 80-20.”

She points out that health insurance is another big expense for school districts that “sits outside of QBE in the budget,” and a financial pressure on school districts that is becoming more acute.

After the 2008 Great Recession forced the state to adopt an austerity budget, in 2011 the Legislature eliminated the state’s contribution to the cost of health insurance for bus drivers, nutrition workers, custodians and other nonteaching, or noncertified, education personnel. That move shifted about $300 million in annual costs to school districts at the time.

Since then, the State Health Benefit Plan premiums have skyrocketed. This year, district leaders were shocked by the governor’s proposal to increase the cost of monthly premiums per noncertified employee to $1,580 from $945, an expense that school districts must now wholly bear. Once fully implemented, in 2025, this will be an additional annual expense of $458 million for local school districts.

“Since districts are already covering the vast majority of the cost of transporting kids safely to and from school, this increase in health insurance costs is going to make it even more challenging for many districts to pay transportation employees competitive wages, and to invest what they need to in transportation operations to provide this vital service,” said PAGE’s Suggs. “Looking ahead, districts are going to have to make some hard decisions. It’s very important to provide health insurance for their employees. So they may have less to invest in the classroom.”

“That really wasn’t fair to districts, to do it all at once,” said Hatchett of the health premium cost jump. “We should have been increasing it all along. But health insurance costs have gone up tremendously, and we had to fill that hole.”

Asked what the state should do to address the funding deficit and operational challenges in student transportation, State School Superintendent Richard Woods offered this response to State Affairs, via email:

“It is absolutely essential that our school systems have the resources they need to transport students safely to and from school. This is an issue I encountered personally as a school leader in rural Georgia and it’s one I hear as I meet with local school superintendents now. Our systems are also facing the headwinds of the overall labor market and nationwide bus driver shortages.

“I have consistently advocated to the state Legislature for increased transportation funding and for modernization of the QBE formula to align state funding with the expenses of a 21st-century education … I appreciate the Legislature dedicating funding for transportation upgrades in recent state budgets and am committed to partnering with them to continue to address this need in the future.”

Doretha Stewart Mitchell, 60, whose daughter, Zhaqueline, has been chronically late to her Augusta high school over the past few years, said, “Well, I hope someone can break the stalemate around busing.”

When the bus has conked out, or failed to show, Mitchell has rounded up the teenagers waiting at the bus stop and taken them to school in her car, sometimes making two or three trips. She said she’s talked many times with the Richmond County transportation director and the principal of her daughter’s school about the impact of “the broken bus system” on her community’s children.

“They tell me they need more drivers, and more funding, and they’re doing the best they can,” she said. “But year after year, it’s the same old argument and the same old outcome. What I say is, if you don’t fix it, you’re not showing me that you value our children.”

Read these related stories:

Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @JOURNALISTAJILL or at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Busing Breakdown Logo: (Credit: Brittney Phan)

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …