Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoPre-COVID, Georgia rated schools for well-being; will ratings resurface?

Richmond County Board of Education (Credit: Tammy Joyner)

- Georgia is the first state in the U.S. to use school climate star ratings as part of its academic accountability system.

- School climate star ratings have helped reduce school suspension rates.

- Post-pandemic, educators seem unsure about the role of a rating system in education.

In part one of a two-part series on the state of Georgia’s School Climate Star Rating system, designed to measure a school’s environment for learning and thriving, State Affairs Senior Investigative Reporter Tammy Joyner looks at the origins of the rating system and how experts view its effectiveness.

AUGUSTA, Ga. — W.S. Hornsby Elementary School and W.S. Hornsby Middle School sit side by side, separated only by a short breezeway. Yet, the two schools couldn’t be further apart when it comes to how students, parents and teachers feel about them.

The schools illustrate both ends of the spectrum of a statewide ratings system that tracks the well-being of Georgia’s roughly 2,300 K-12 public schools. Hornsby Elementary earned five stars, the highest score in the Georgia School Climate Star Rating system, in 2019, the most recent data available. The middle school received one star, the lowest score.

While the School Climate Star Rating system is not a measure of academic achievement, it is a glimpse into whether a school is a good, safe environment for learning. And the system has received national acclaim.

Following nearly three years of a pandemic that kept children from a structured learning environment, how and will the state address — and continue to fund — this critical reporting measurement?

The answer to that question is unclear.

Experts are not in sync on what potential external and other issues make one school divided by a breezeway a one-star and the other school a five-star.

“Anytime you’re trying to take [a measure of] a very human and intangible thing like school climate, it’s imperfect. It’s so difficult to nail down and quantify,” said Leslie Hazle Bussey, CEO and executive director of the Georgia Leadership Institute for School Improvement in Duluth and a former Richmond County school district consultant.

Students and schools throughout Georgia and the nation are increasingly under siege in and out of the classroom. School shootings and ensuing trauma impact students, teachers, parents and administrators whether the attack is on their campus or one across the country. Complicating matters, say experts, are teacher and staff shortages, COVID-19-related fatigue and a surge in student behavioral problems.

The discipline factor

Georgia’s statewide School Climate Star Rating program is the result of a decades-old effort to cut the number of bullying incidents and out-of-school suspensions.

“Georgia had a very high out-of-school suspension rate,” said Michael Waller, executive director of Georgia Appleseed Center for Law & Justice, a nonprofit child advocacy group in Cobb County that works to keep kids in school. Georgia Appleseed was part of the school climate reform movement.

“We were suspending kids in record, remarkable numbers. Some [schools] 10%, 12%. Some places had 20%, even higher of kids suspended every year from school. That puts a lot of pressure on students. They’re out of school, not learning and they’re disengaged from school. It creates a churn in the school.”

During the 2009-2010 school year — around the time school climate reform was taking shape — about 142,000 kids, or 8.1% in K-12 statewide, received out-of-school suspensions, according to DOE records. Waller said that last year, the number of suspensions had dropped to 6.5%, or 118,000 kids.

“That’s fewer kids being suspended even though we have a larger population of school kids now,” Waller noted.

A 2019 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that nationwide 19% of students in grades 9-12 were bullied in school in 2018. And in Georgia, bullying was so pervasive that the state mandated that all state or federally-funded schools implement anti-bullying policies. That same year, the state made bullying a misdemeanor.

“The Department of Education and the state of Georgia have a lot to crow about when it comes to school climate reform,” said Waller. “They got school climate reform into 50% of the schools at least. They made a huge dent in discipline. Schools are improving it, making it more effective, making it more supportive of kids. They’re [Georgia] a leader in the nation on school climate reform.”

Will the star system stay or go?

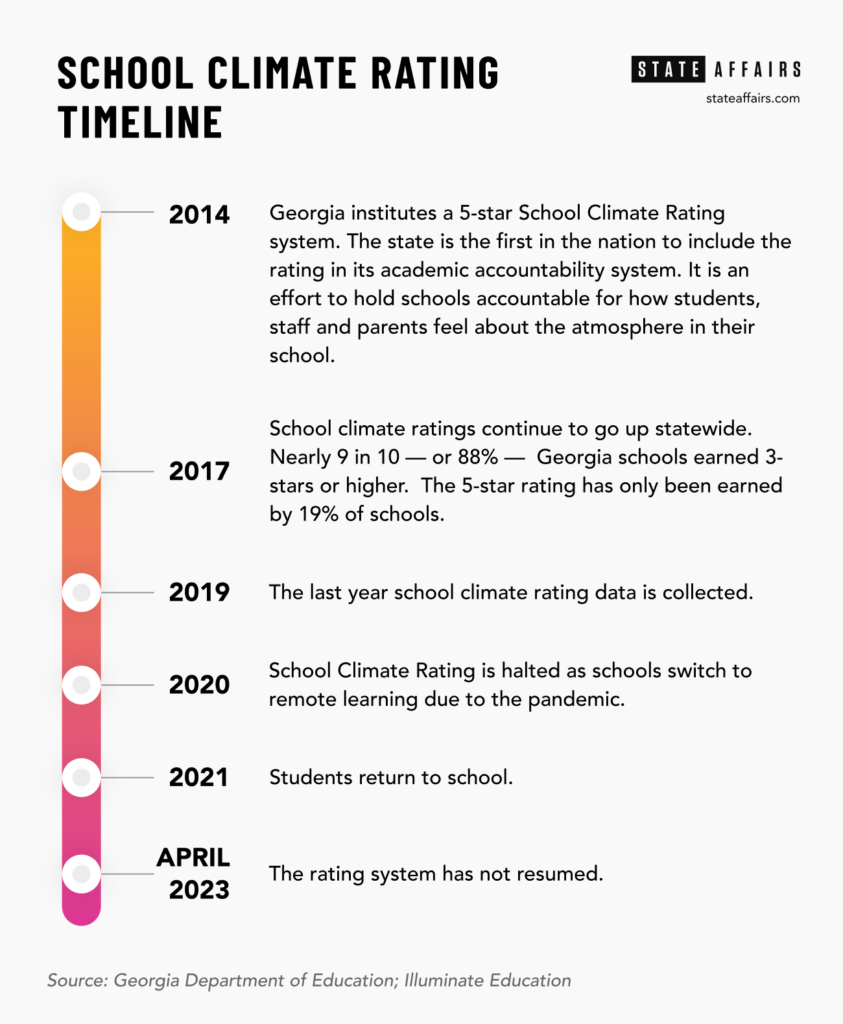

The School Climate Star Rating program was halted in 2020 when COVID-19 hit. It has yet to resume, and some question whether it will.

“We are currently evaluating when the star rating can be reinstated to ensure valid and reliable data,” Meghan Frick, a spokesman for the state Department of Education (DOE), told State Affairs in an email.

DOE officials may be considering revising parts of the system, according to several people familiar with it.

“School climate is sort of the essence of what makes a good school,” Caitlin Dooley, a former DOE deputy superintendent who oversaw the School Climate Star Rating, told State Affairs. Dooley left the job last December to become executive director of Voices for Georgia’s Children. It costs between $2 million and $3 million a year to administer the School Climate Star Rating program statewide, Dooley said. That was for personnel, she said.

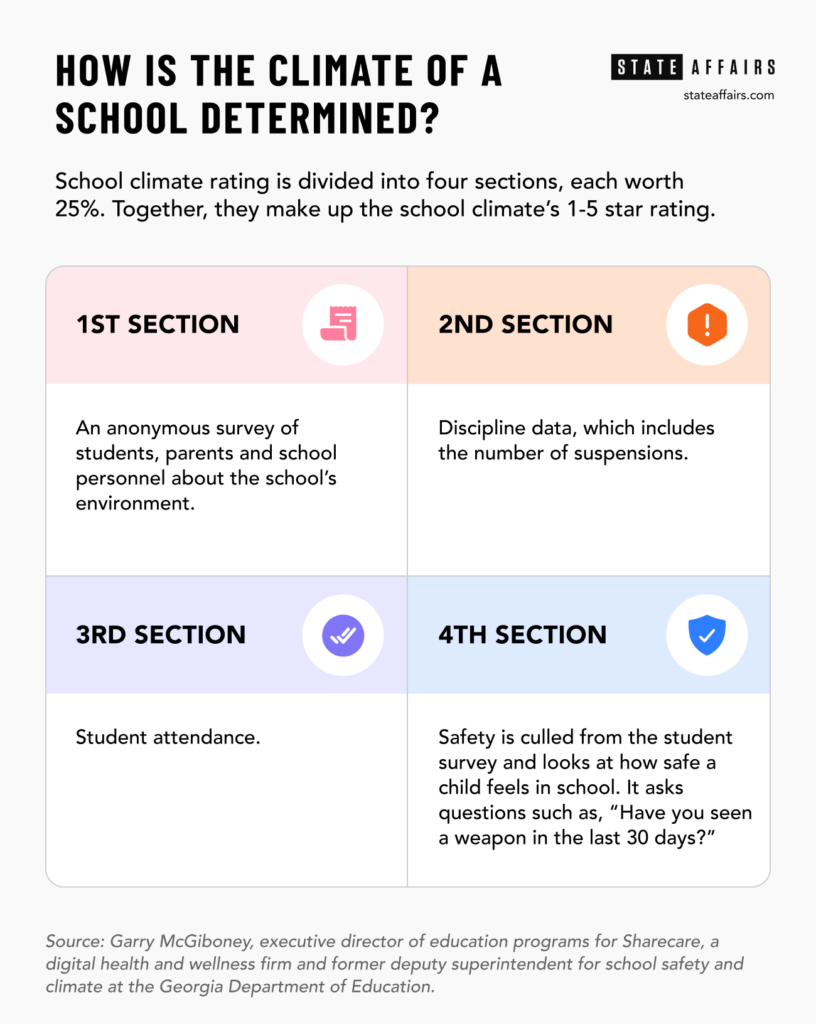

The rating system is calculated using data from the Georgia Student Health Survey, Georgia School Personnel Survey, Georgia Parent Survey, student discipline data and attendance records for students, teachers, staff and administrators.

“When you walk in the building, it’s that warm feeling you get. It encourages kids to come to school, and it provides the metrics for school systems to use to improve,” said Dooley, who oversaw the program from 2020-2022. “It’s a foundation for learning, going to a school that is a comforting place, a school where people greet you at the door and talk to you while you’re there. A school where you feel like you’re safe, and you have a sense of belonging and you feel like you have a friend. Those are places where you would have the cognitive capacity to learn.”

That’s a lofty goal — and a foreign concept for some schools struggling to reach and teach children trying to survive in chaotic homes and communities.

“The climate of the community is not separate from the climate of the school when it comes to our children,” said Wayne Frazier, a former middle and high school principal now in his sixth year as a member of Augusta’s Richmond County School Board.

“We just had a fourth grader witness her daddy shooting and killing her mother. Then the police came and shot him in front of the little girl. That has become the norm in certain communities.,” said Frazier. “We get these kinds of calls on a regular basis. So they bring with them this type of trauma to the school. Behavior, academics. It impacts everything,”

Some educators, school board officials, education experts and child advocates agree, noting that the rating system doesn’t tell the whole story of what’s going on inside a school.

State Affairs repeatedly reached out to state school Superintendent Richard Woods and key DOE officials over the past seven weeks for details on the program, its funding and its fate but had not received a response by the time this article was published.

Praise vs. punishment

Georgia was the first state in the country to include school climate as an early indicator in its academic accountability system. It is now one of 35 states with school climate policies. The Peach State is one of only a dozen states where the school climate system is required in all K-12 public schools, according to the National Association of State Boards of Education.

The majority of Georgia schools earned 3 out of 5 stars in 2019, according to the latest Georgia data available. At that time, 33 schools, including Hornsby Middle, ranked at the bottom with one star. In Richmond County, four other schools also received one star.

Overall, school climate ratings statewide were an average of four stars in 2019, unchanged from 2018 but up slightly from 2016 when the average was 3.5 stars.

Education experts and advocates credit a set of tools called Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports, or PBIS, with helping improve school climate statewide over the years. PBIS focuses on praising rather than punishing students and redirecting, when possible, a student’s behavior to get a better outcome. It has been known to improve academic performance and perceptions of schools, education experts say. It also has reduced suspensions, anti-social and aggressive behavior, bullying, drug use and teacher turnover, according to the Center on PBIS.

State Affairs found fewer than 10% of the 33 schools that received a one-star rating in 2019 were using PBIS.

The architect

Garry McGiboney is widely hailed as the architect behind much of what has made the School Climate Star Rating system work in Georgia.

In 2007, the veteran educator, certified psychologist and leading expert in leadership and school behavior arrived at the state DOE.

When McGiboney arrived, only 70 of the state’s 2,300 public schools were using PBIS. By the time he left in October 2020, PBIS was being used in 1,400 Georgia schools.

“There’s different ways to improve school climate,” McGiboney, author of several books, including The Psychology of School Climate, told State Affairs. “I wanted something that was research-based. It [PBIS] was a good framework for improving climate at school.”

McGiboney is now executive director of government and education programs at Sharecare, an Atlanta-based digital health and wellness firm co-founded by WebMD founder Jeff Arnold.

“The research for several years has shown that the climate of the school is really instrumental in the safety of the school but also in the academic engagement,” said McGiboney. “Students are learning … because if they don’t feel safe or secure, they don’t feel connected.”

DOE research shows student attendance significantly impacts student achievement. Missing more than ten days of school a year — regardless of the cause — can affect a student’s academic performance and their attitude about school. Attendance accounts for one-fourth of the equation of what factors into school climate ratings.

The DOE study, conducted in 2011, found a substantial drop in student graduation rates as it relates to absences among eighth, ninth and 10th graders. For example, an eighth grader who missed 11 to 14 days of school had a 52.33% chance of graduating while his peer who hadn’t missed any school days had a 79% chance of graduating.

Also, schools with strong school climate ratings tend to have fewer discipline incidents overall, Appleseed executive Waller said.

“If you eliminate a bunch of discipline incidents that don’t need to be incidents at all, you can focus on the kids who need extra support and help,” Waller said. “You’re not distracted and you’re not creating a negative climate of punishment for smaller incidents that really shouldn’t be there at all. You also end up with higher student performance as a result; you also end up with higher teacher retention because they’re happier.

“It has made a huge difference for children.”

A glimpse of the data shows mixed results. Between 2015 and 2019, schools across the state saw:

- Out-of-school suspensions and in-school suspensions fall.

- Assignments to alternative schools rose while school expulsions declined.

- Students’, teachers’ and parents’ perception of their schools improved.

- Physical altercations rose.

- Bullying and harassment decreased.

- Drug-related incidents more than tripled.

The School Climate Star Rating has sparked some controversy over the years. Allegations surfaced at one point that discipline data was being underreported in some schools.

State lawmakers introduced a bill in 2021 to drop discipline data from the School Climate Star Rating system. The bill passed, but without that measure, leaving discipline data intact.

There’s more than meets the eye

While the rating system provides useful data on schools and districts, it’s not the definitive measure of what’s really going on in schools, according to Bussey, who has worked with a number of Georgia’s 180 school districts statewide.

“It runs the gamut. You’re going to have high climate ratings that are pretty legit. You’re going to have low climate ratings that aren’t [but] you’ve got a beautiful culture where parents and students feel deeply loved and are known and are learning but for whatever reason, maybe you’d have a low parent participation rate on your surveys,” Bussey said. “Maybe you had a particular community that was really struck with COVID. So you have a lot of absences, either by students or teachers. Those things could skew everything and give you a one- or two-star climate rating but it’s actually a beautiful place.

“You could have a situation where you’ve got five stars but if you and I walk into that school, we would patently feel that this is not a beautiful place for humans to grow and learn.”

Bussey commended state education department officials for collecting “data on every single school, every district, every year that’s comparable.” But she said some districts, educators and even parents have become good at figuring out “what causes us to get more stars.”

“There’s a way to mechanize those numbers so that they appear like it’s a great climate. But when you go in there people aren’t [thriving],” Bussey said.

Improving a school’s environment doesn’t happen overnight, she said, it can often take years.

“I don’t think [School Climate Star Rating] in itself is a mechanism for improving schools any more than when you go to the doctor and they weigh you,” she said. “Weighing you doesn’t change your health. All it tells you is something on that one day.”

Want to see how your individual school or school district performed on the last School Climate Star Rating? Find out here.

You can reach Tammy Joyner on Twitter @lvjoyner or at [email protected]. Joyner is State Affairs’ senior investigative reporter in Georgia. A Georgia transplant, she has lived in the Peach State for nearly 30 years.

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Correction, May 5, 2023: This story has been updated to remove the length of time suspended students were reported to be out of school.

Part two:

Know the most important news affecting Georgia

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …