Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoDo Georgia’s low-income students need more state school funding?

Illustration by Brittney Phan (State Affairs)

- More than half a million Georgia students live in poverty or other underprivileged situations.

- Georgia is one of only six states that do not factor low-income students in its school-funding model.

- Many state lawmakers and experts agree Georgia’s funding model needs an update – but no progress has been made.

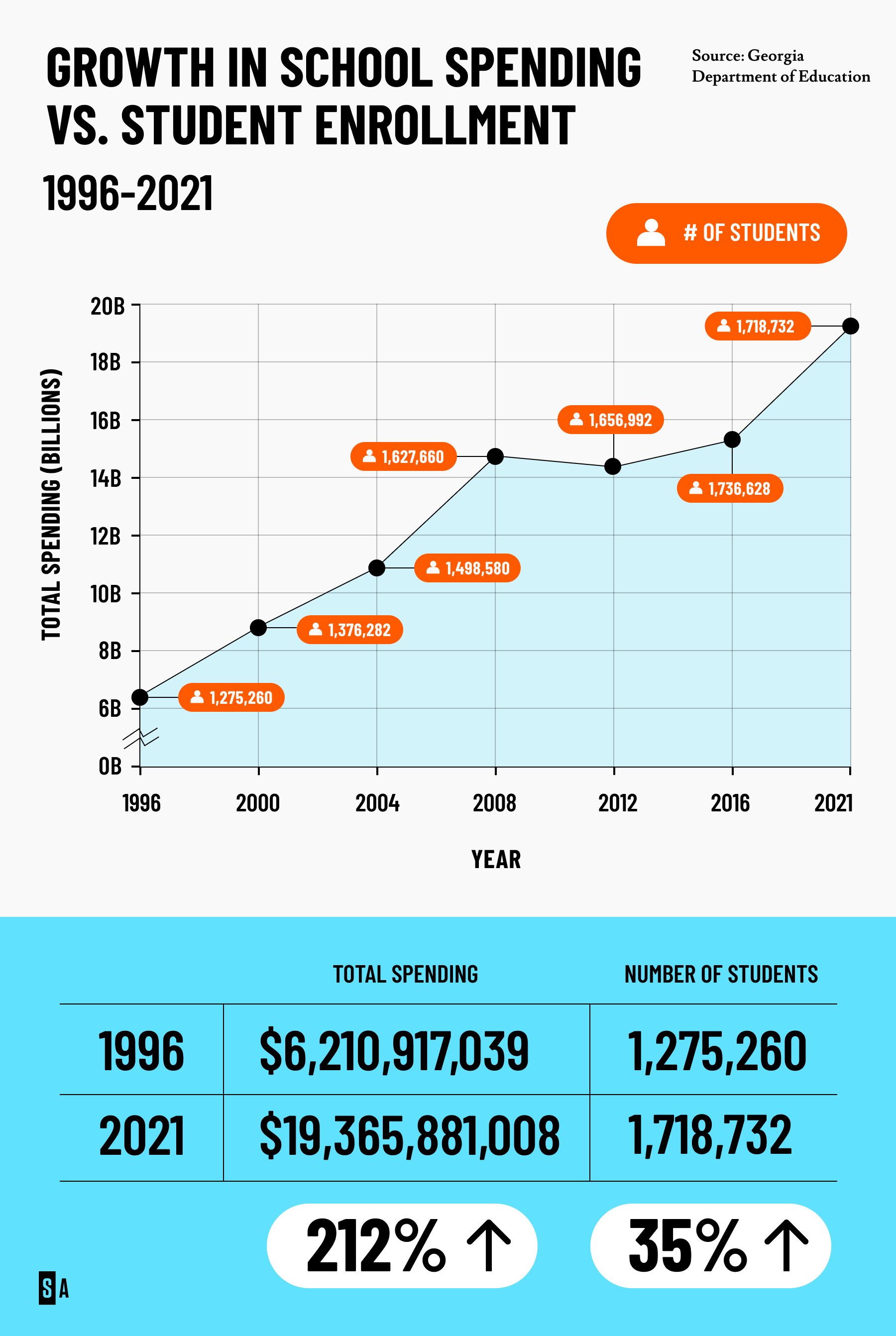

Taxpayers spend billions of dollars each year on Georgia’s public k-12 schools, but none of the state’s education dollars goes specifically to kids from low-income families who often struggle in class, State Affairs has found.

Georgia is one of only six states that do not factor low-income students into their annual school-funding formulas – even as roughly one-third of Georgia’s roughly 1.7 million students in county and city public schools were classified by the state as living in poverty last year.

The omission has prompted some state lawmakers and policy experts to call for overhauling Georgia’s complex funding formula for schools. Others doubt the General Assembly has enough political will to change the nearly 40-year-old system that decides how to spread more than $12 billion among 2,300 local schools.

“We haven’t had someone take a hard look at what kids need, at least since I’ve been following it,” said Stephen Owens, a senior policy analyst with the nonprofit Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI) who focuses on education issues. “I think it comes from a fear that we will be shown to be far behind.”

In this story, State Affairs digs into Georgia's complex model for funding public schools and how many of the state's neediest children miss out on extra funding.

Georgia's school funding 'phone booth'

Benjamin Scafidi, an economics professor at Kennesaw State University who studies national trends in school finances, remembers stories of the grinding tug-of-war in 1985 between state lawmakers tasked with creating a new formula for public school funding.

Each new proposal prompted fresh calculations in the old computers of the budget office across from the Capitol building in Atlanta, spurring lawmakers to haggle over the final bill so that their own school district wouldn’t miss out on state tax dollars.

“That’s why it’s so difficult to change the formula,” Scafidi said. “If you change one comma, there’s winners and losers. And the losers are going to scream.”

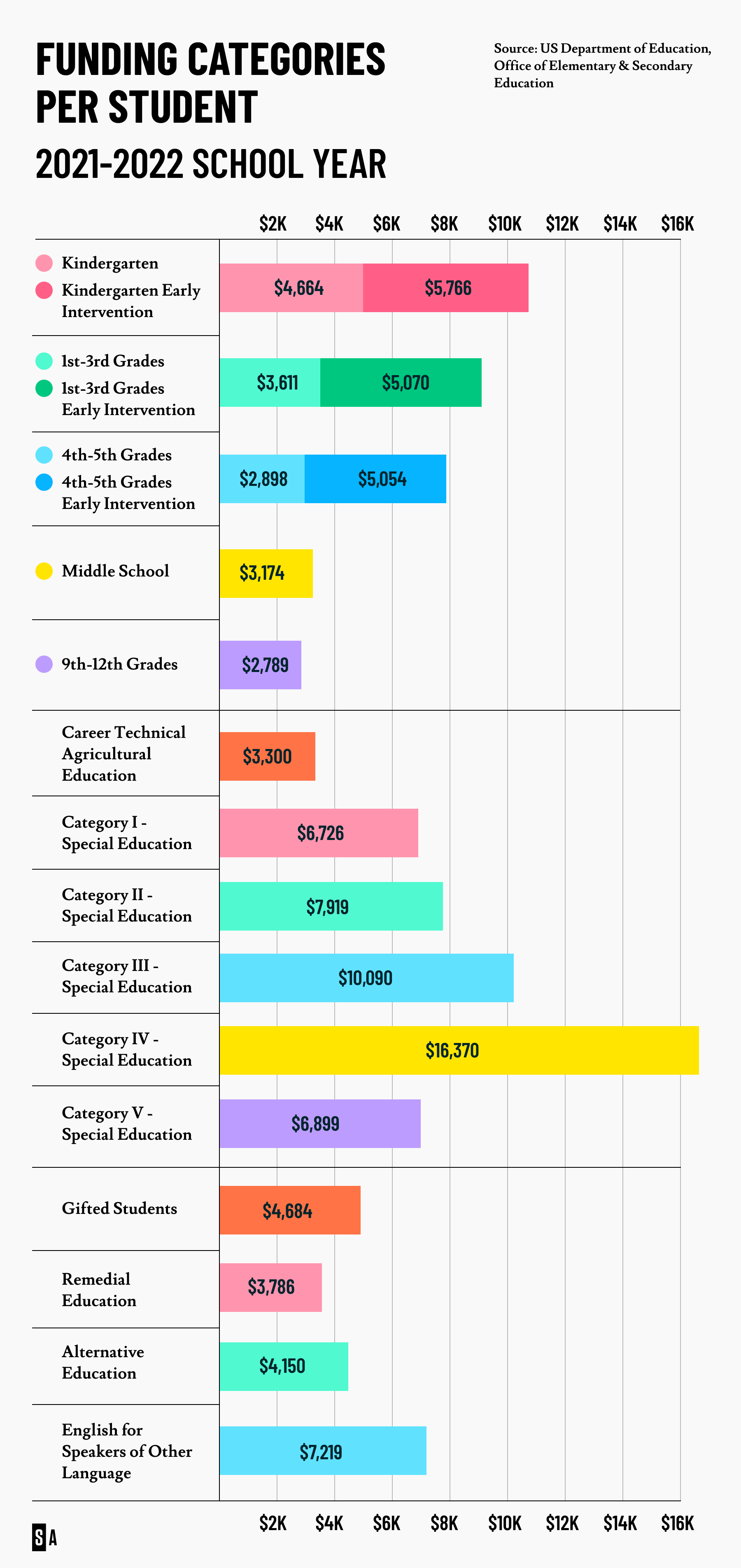

What resulted was the “Quality Basic Education” formula, a complicated system that portions out billions of dollars based on a blend of schools’ student numbers and their academic programs. It ties dollar amounts to each student depending on their grade or special-education needs – but not based on whether they come from low-income backgrounds. In the current 2021-22 school year, schools received between roughly $2,800 and $4,700 in state funds for each student in kindergarten through 12th grade, plus higher amounts per student for programs in special education, academic intervention and English learners.

Those baseline per-student funding rates don’t cover all the math that goes into the formula, which many analysts and lawmakers agree is a tough system for anyone to understand.

“You could fit everybody who truly understands the QBE formula certainly in a room, maybe in a phone booth,” said Kyle Wingfield, president and CEO of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation (GPPF). “You’re fitting programs today into categories created all those years ago and it doesn’t even necessarily make sense anymore.”

Low-income students miss the math

While the formula covers basic educational needs, it doesn’t factor in students from low-income backgrounds whose grades stumble without extra help from teachers or tutors – which many schools can’t afford.

Georgia is an outlier among states for not including funding for low-income students in their school-funding models, joining Florida, Alabama, Arizona, South Dakota, Idaho and Alaska in not doing so, according to the nonprofit Education Commission of the States.

Last school year, around 541,000 students were “directly certified” by the state, a marker of Georgia’s student poverty levels that tracks kids whose families receive food stamps, housing assistance or are homeless. Additionally, more than half of Georgia’s k-12 students qualified for free and reduced meals – another marker of student poverty.

Schools with large shares of their students below the poverty line rank among the lowest in Georgia for testing and other academic-performance measures, state data shows. Out of 38 school districts with most of their students from low-income backgrounds, nearly all received “D” or “F” grades on the state’s most recent school report card – a metric that assesses test scores, graduation rates and students’ learning progress.

The lack of formula dollars for low-income students also widens funding gaps between schools in wealthy areas and those with higher poverty levels that local property taxes, equalization grants and federal aid don’t completely close, experts say.

Funding for Georgia’s highest-poverty schools is “severely inadequate,” totaling less than half the amount likely needed to help bring test scores up to the national average, according to a December 2021 study from the nonprofit Albert Shanker Institute and Rutgers University.

“We have these huge differences in how low-income kids are doing compared to kids who are not on free lunch,” GBPI’s Owens said. “There are higher costs associated with the higher needs of students.”

Piecemeal approach in the legislature

Amid issues for low-income students, recent efforts to tweak Georgia’s school funding have gone nowhere in the General Assembly – despite calls from many lawmakers and experts for an update.

Several changes to the formula proposed in 2011 by a commission backed by then-Gov. Nathan Deal failed to translate into actual legislation. The Georgia Chamber of Commerce also pitched a formula overhaul that would include more consideration for low-income students, but which didn’t gain traction in the legislature.

Instead, lawmakers have tackled school-funding issues in piecemeal fashion – but without much success. Deal’s proposal for the state to assume oversight of low-performing schools was struck down by voters in 2016, followed by the legislature’s creation of a new state office for turning around struggling schools that collapsed within three years.

Since then, the most sweeping proposed funding changes have come from state Rep. Wes Cantrell, R-Woodstock, who has a pair of school-voucher bills in the current legislative session that would allow students to use state funds for switching schools, home-schooling or tutor services.

Cantrell said his proposals would directly benefit students who are struggling in school, avoiding the tough sell needed to convince a majority in the General Assembly to change the funding formula.

“We can’t seem to move the needle with the formula,” Cantrell said. “So now, you have some counties that have a lot more than others, even with all the efforts to make it equal.”

Opponents worry student vouchers would send state dollars to private schools at the expense of public education. They want the state to take an in-depth look at how Georgia could spend its education funding in more effective ways – including whether schools currently have enough money for low-income students.

Meanwhile, many lawmakers like Georgia House Minority Leader James Beverly (D-Macon) support legislation that would create a new way for the funding formula to account for low-income students. A bill to do so has stalled recently in the legislature.

“That should be something we’re talking about right now,” Beverly said. “It would add a little bit more to the formula for school systems so we can make sure kids don’t fall through the cracks.”

What else do you want to know about the costs and taxpayer funding of Georgia's public schools? Share your thoughts/tips by emailing: [email protected].

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

House speaker Jon Burns hires new communications director

House speaker Jon Burns, R-Newington, announced today that he has hired a new communications director. Kayla Roberson, who has served as press secretary at the Georgia Chamber for the past year or so, will now oversee all external communications, media relations and strategic messaging for Burns. “I’m excited to welcome Kayla to our team,” Burns …

Global bird flu disrupts Georgia exports, costing chicken producers millions

ATLANTA — A global bird flu that has rapidly spread from birds to dairy cows, milk supplies and humans has cost untold millions of dollars in lost export business in Georgia, the nation’s leading poultry producer, officials with the state Department of Agriculture and poultry industry said.

Georgia has had only three reported cases of H5N1 avian influenza since it reemerged in 2022. The last of those cases was resolved in November 2023 but ramifications of those outbreaks continue to have a big effect on the state’s ability to export chicken and chicken parts, such as chicken feet, to different countries, including China, one of Georgia’s biggest export markets for chicken feet.

In 2022, frozen chicken feet, for example, accounted for more than 85% of all U.S. poultry exported to China, according to Farm Progress, publisher of 22 farming and ranching magazines.

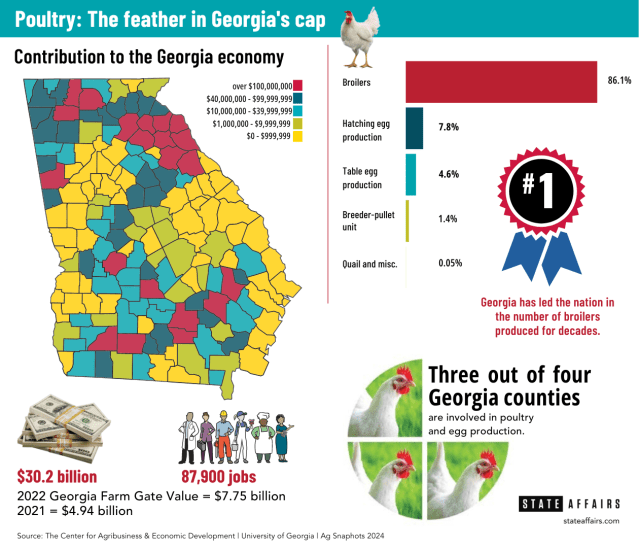

The $30 billion poultry industry is Georgia’s largest segment in its No. 1 industry — agriculture.

China has also placed a ban on the import of chicken products from 41 other American states. The ban on Georgia products went into effect Nov. 21, 2023. Efforts to reach the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C. were unsuccessful.

Georgia Poultry Federation President Mike Giles estimates the state’s loss at “well into the millions of dollars.”

“It’s a significant amount in a significant export market for us,” he said. “Poultry paws [feet] immediately lose value because of the loss of demand.”

The ban has forced Georgia poultry producers to find alternative markets for their products that would normally be headed to China.

“Some are sold domestically, some are frozen and stored, hopefully to find markets later on, and some go to other countries,” Giles said.

This isn’t the first time China has banned U.S.-produced poultry products due to a bird flu outbreak. The country instituted a ban in January 2015 which lasted until November 2019 — even though U.S. poultry products were deemed free of the disease by August 2017.

After that ban was lifted, China’s appetite for American-produced chicken products became voracious.

In 2022, U.S. producers shipped nearly $6 billion in poultry meat and related products (excluding eggs) to over 130 countries. China has emerged as the second largest destination for U.S. poultry exports, increasing from $10 million in 2019 to a record $1.1 billion in 2022, according to Southern Ag Today.

Chicken paws, for instance, are eaten in many Asian countries, including the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia and Korea.They can also be found on Chinese dim sum menus throughout the U.S. and are also popular in Jamaica, Trinidad, Russia and Ukraine in everything from soups and curries to fried snacks.

Three Georgia counties have reported H5N1 outbreaks since 2022. The most recent case was late last year. Henry, Sumter and Toombs counties each reported one case of H5N1 bird flu. Those outbreaks are resolved, poultry and state agriculture officials say.

“When HPAI cases are found in any state, that state is given a designation that could lead to foreign countries halting trade on poultry products from that state,” Georgia Department of Agriculture spokesman Matthew Agvent told State Affairs.

Not since 2016 has the United States experienced such a fast-moving case of the H5N1 avian influenza. In the last two months, the virus has spread in parts of the United States from birds to dairy cows, some milk supplies and humans. Two people — a Texas dairy worker and a prison inmate in Colorado who was killing infected birds at a poultry farm — are reported to have caught the virus, according to news reports. The outbreak is the largest in recent history, impacting both domestic poultry and livestock as well as wild birds and some mammal species.

State officials are continuing to monitor the national outbreak and its impact on Georgia.

Georgia’s poultry & egg industry: At A Glance

Annual economic impact: $30.2 billion

Percentage of the Agriculture industry: 58% *

Jobs: 87,900

Counties involved in poultry & egg production: 3 out of 4

National ranking in chicken broiler production: No. 1

Daily production of table eggs: 7.8 million

Daily production of hatching eggs: 6.5 million

Pounds of chicken produced daily: 30.2 million

Pounds of chicken produced annually: 8 billion

Number of chicken broilers processed each day: 5 million

Counties involved in poultry & egg production: 3 out of 4

Source: Georgia Poultry Federation; The Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development, University of Georgia, Ag Snapshots 2024; Georgia Poultry Federation.

Have questions? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs and drink milk? Answers to your most pressing questions about the latest bird flu outbreak

A two-year-old strain of bird flu has heightened concerns in Georgia and the rest of the country after the virus recently spread to dairy cows. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and its impact on Georgia and the rest of the country. What are the symptoms of this flu in humans? Eye …

Kemp signs bills on education, health care, taxes

Gov. Brian Kemp signed a slew of bills over the past week or so, including the private school voucher bill long sought by Republicans and a bill that will ease regulations over the construction and expansion of medical facilities in rural areas. His bill-signing events were clustered into themes: education, health care, military members, human …