Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoMental health crisis care, protections for sober living homes among behavioral health bills on tap

On Jan. 18, 2024 at the State Capitol, John Langston (left), a recovery community organizer in Jackson; Kevin Tanner, commissioner of the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities; and Jeff Breedlove, advocacy strategist for the Georgia Council for Recovery advocated for legislation to require the installation of opioid drug overdose reversal kits in every state facility in Georgia. (Credit: Jill Jordan Sieder)

In a state where 1.4 million adults out of a total population of 11 million have a mental health condition, and about a third of those who need care do not receive it, Georgia lawmakers are starting to drop and develop legislation to address these citizens’ needs.

Legislators and advocates say the biggest priority around behavioral health, which includes mental health and addiction recovery, remains to tackle the severe shortage of behavioral health workers in the state — including psychiatrists, psychologists, recovery specialists and counselors — in state-run facilities and private health care settings.

To that end, they expect major provisions in House Bill 520, the 51-page bill introduced last year to further implement the Mental Health Parity Act of 2022, which got strong support in the House but didn’t pass in the Senate, to resurface in multiple pieces of legislation this session. House and Senate leadership are signaling support for this year’s round of major mental health legislation.

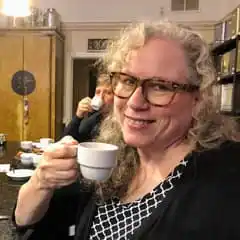

Rep. Mary Margaret Oliver, D-Decatur, a co-sponsor of both mental health bills, said a key to growing the behavioral health workforce is to increase their compensation by implementing the results of the 2023 Medicaid behavioral health provider review, which found that Medicaid reimbursement rates for Georgia’s providers are significantly lower than in other states. The Department of Community Health would need to work with the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to do so.

In the meantime, other behavioral health-related bills are emerging.

House Bill 913, titled the EmPATH Georgia Act, filed this month would establish a grant program within the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities to create emergency psychiatric assessment, treatment and healing (EmPATH) units in hospitals around the state.

EmPATH units are designed to respond to people experiencing a “brief, intense crisis” who often show up at hospital emergency rooms. Within an hour they are guided to a calming space and provided with outpatient treatment that could include counseling, detoxification, stabilization services and prescribed medications. Such immediate treatment has proven to reduce the need for in-patient hospitalizations and significantly lower the cost of crisis care for patients in other states.

House Bill 873 would create new Juvenile Treatment Court divisions within the juvenile court system to provide an alternative to how juvenile delinquency and truancy cases are handled. The goal is to reunify youth with their families, keep them in school and reduce the use of detention. As with adult accountability courts, the focus is on rehabilitation of youth through “early, continuous and intense judicially supervised treatment” to reduce alcohol or drug abuse and addiction, treat their mental and behavioral health needs, and prevent and reduce gang involvement.

The bipartisan bill’s main sponsor is Rep. Stan Gunter, R-Blairsville, a former superior court judge, who said he saw the positive impact of such drug and mental health accountability courts on adults.

Senators plan to pursue Senate Bill 331, which Sen. Randy Robertson, R-Cataula introduced late in the last session. It would provide a certification and oversight process for addiction recovery homes.

Last week Todd Wilson, executive director of the Georgia Association of Recovery Residences, which represents 100 homes serving 10,000 people annually, said more regulations and oversight are needed to make sure such residences, which do not require a license to run in Georgia, operate in ways to “ensure safety, quality and ethical standards” and are designed to “protect vulnerable individuals” seeking to overcome addiction and “recover their lives … in an environment inducive to their success.”

Other pending legislation not yet filed would repeal state law that mandates a six- to nine-month waiting period for any zoning decisions related to the location or relocation of a halfway house, drug rehab center or facility for treatment of drug dependency.

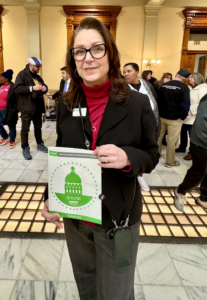

The decades-old law violates the Americans With Disabilities Act, said Kim Jones, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, Georgia chapter. She noted this federal legislation defines someone in recovery who is no longer engaging in the illegal use of drugs as a person with a disability

“There is no other [zoning] law like that for other facilities, so we find that discriminatory against people in recovery,” said Jones, who added that zoning delays add significant development costs to such projects and “build up support for not-in-my-backyard” sentiments among community members.

Read these related stories:

Have questions, comments or tips? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Professionals still face licensing delays amid state’s transition to online system

The Gist Georgia’s professionals and business owners are still struggling to obtain professional licenses in a timely manner. As the Secretary of State’s Office rolls out its new Georgia Online Application Licensing System to expedite the process, the efficiency of this new process is being put to the test. What’s Happening Thursday morning at the …

Controversy over AP African American Studies class grows

Rashad Brown has been teaching Advanced Placement African American Studies at Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School for three years. He’ll continue to do so — even though the state’s top education official removed it from the list of state-funded course offerings for the upcoming school year. While Brown prepares to start teaching his class on …

Students, teachers, lawmakers blast decision to end AP African American history classes

ATLANTA — A coalition of lawmakers, civil rights leaders, clergy, educators and students Wednesday called on the state’s education czar to rescind his decision to drop an advanced placement African American studies class from the state’s curriculum for the upcoming school year. “This decision is the latest attack in a long-running GOP assault on Georgia’s …

Kamala Harris’ presidential bid reinvigorates Georgia Democrats

Georgia Democrats have gained new momentum heading into the November election, propelled by President Joe Biden’s decision to bow out of his reelection bid and hand the reins to Vice President Kamala Harris. The historic decision, announced Sunday, is expected to prove pivotal in the national and state political arenas and breathe new life and …