Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoHow not to become Putin’s hostage

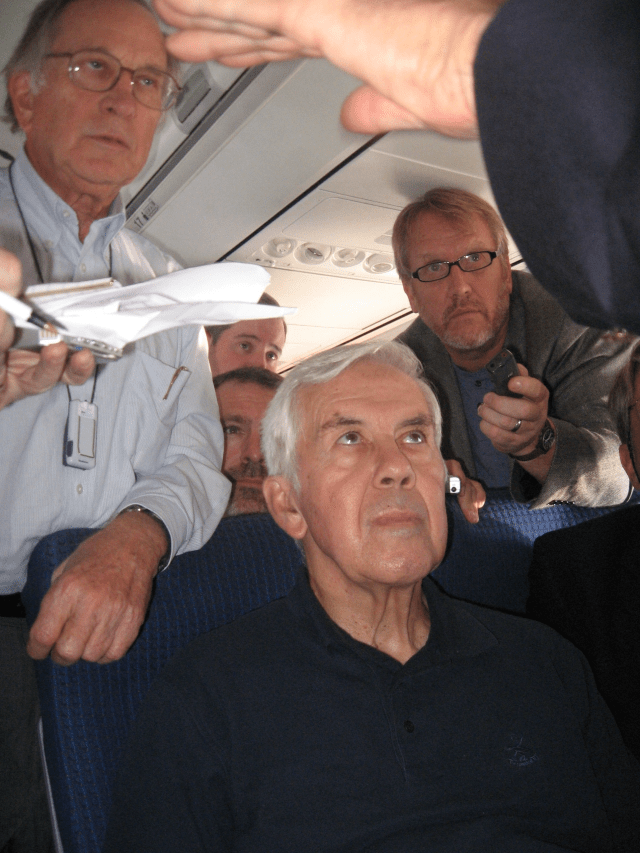

Sens. Richard Lugar, left, and Sam Nunn meet with Sergey Lavrov at the Foreign Ministry Building in Moscow. (Credit: Brian A. Howey)

INDIANAPOLIS — Here’s some good advice if you’re an American journalist, basketball player, business executive or tourist: Don’t travel to Russia. You could end up as a hostage and bargaining chip of the Russian despot Vladimir Putin.

On Thursday, the world witnessed the most complex prisoner exchange since the Cold War, with the release of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich; former U.S. Marine Paul Whelan; Washington Post columnist Vladimir Kara-Murza, a dual Russian-British national critical of the Kremlin; and Alsu Kurmasheva, a Russian-American reporter with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

They were part of a six-nation prisoner swap that included Russian assassin Vadim Krasikov, who was convicted and imprisoned in Germany.

I offer this travel advice through the prism of personal experience. In August 2007, I journeyed with Indiana U.S. Sen. Richard Lugar and former Sen. Sam Nunn of Georgia to Moscow, Siberia, Ukraine and Albania. My visa stated I was a working journalist for Howey Politics and Indianapolis Monthly Magazine. I’m sure that tidbit raised red flags at the Federal Security Service, the Russian internal security and counterintelligence service.

Could this Brian Howey be just an American schmoe reporter, or is he a CIA asset? A spy?

No. Yes. No. No!

While attending a Carnegie Institute conference on our second day in the capital, I returned to my room at the Moscow Marriott Grand to find my papers riffled through and scattered about. The spook made no attempt to be clandestine. I had my laptop with me, so they didn’t have access to that.

I immediately told Sen. Lugar’s communications director, Andy Fisher. He wasn’t surprised. Federal Security Service agents frequently stalked the hotel hallways of congressional delegations, or “codels.”

After delegation visits north of Moscow (to watch the bilateral destruction of a Soviet-era missile motor) and to Siberia (to visit a plant built by Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction funds that destroyed chemical nerve agents), we ended up in Yekaterinburg.

This is the city where the Federal Security Service in 2023 had detained Gershkovich, pulled out of a restaurant with his shirt over his head and dragged away by agents. He was later tried and convicted of espionage in a sham of a trial and sentenced to 16 years in a Russia gulag. Yekaterinburg was a Russian mob-controlled city and the site where Czar Nicholas’ family had been massacred by the Soviets after the coup d’état of 1917.

I had eaten dinner with Nunn the previous night at Yekaterinburg’s World Trade Center building to discuss his possible 2008 presidential candidacy. The next day we were scheduled to depart for Odesa, Ukraine.

At the Yekaterinburg airport I heard the words no American journalist ever wants to hear: “We don’t have your passport.”

“You’re kidding,” I suggested to the Russian attendant at the passport office while glancing at U.S. Navy Chief Floyd Logan. For the past week, Logan had kept every passport of the codel rubber-banded together and close to his vest.

Logan shook his head. Quickly, he and Navy Capt. Gene Moran, the Navy/Senate liaison, started working their phones and BlackBerries. I noticed members of the U.S. embassy staff were pacing while talking on their phones. Could this be a brewing international incident like the one in 2005 when Sens. Lugar and Barack Obama were detained for three hours in Perm?

I spotted Nunn and Lugar arriving at the terminal, and I realized the Navy flight would be departing for Odesa soon.

“Where could it be?” I asked Moran. He arched his eyebrows. Nobody knew.

Could the Federal Security Service be looking for a trophy Yankee journalist as a future bargaining chip? Were they just making a copy?

I began to resign myself to staying in Yekaterinburg for a day or two, or … who knows?

Suddenly the Russian attendant blurted, “I found it!”

Minutes later our naval flight took off. Once in the air, I turned to Kenneth A. Myers III, who served on Lugar’s Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff and later headed the Pentagon’s nuclear program.

“What the fuck was that about?”

“They probably just wanted to take another look at you,” Myers said. “She had big plans for you tonight, Brian.”

That night at the Londonskaya Hotel near Odesa’s famed Potemkin Stairs, where Lugar staffers and I had cocktails, a shadowy figure sat at the end of the smoky bar. Every time I glanced his way, he was looking at me while taking drags on a cigarette. Later, three young men were seated at a nearby table. They started peppering us with questions: How long have you been here? Where are you going?

A member of our group answered, “Tirana, Albania.”

One of the men observed, “There are no flights from here to Tirana.”

It all makes for a great story now, since that was where their questions ended. But it was also a precursor to how dangerous it was and still is to be a journalist in Russia. Since Putin took power in 2000, hundreds of Russian journalists have been killed or disappeared.

On Oct. 7, 2006, Anna Politkovskaya was assassinated in her Moscow apartment building’s elevator after becoming Putin’s most conspicuous critic. On Jan. 5, 2024, Zoya Konovalova, editor-in-chief of the internet group of the state-controlled Kuban broadcast company, was found dead alongside her ex-husband. Preliminary reports suggested she was poisoned. There have been hundreds of similar atrocities in between.

“Multiple Russian sources told me that, according to their knowledge of how Russia’s government operates, such a consequential action — the first arrest of an American journalist on espionage charges since the Soviet era — could not have been authorized without President Vladimir Putin’s assent,” Anna Nemtsova, the Moscow correspondent for Newsweek and The Daily Beast, wrote in an article for The Atlantic. “They also said that the razrabotka, an old KGB term for a surveillance and investigation operation, had begun against Gershkovich weeks before his arrest.”

She quoted Moscow attorney Ivan Pavlov: “Now the rules have changed. Every accredited correspondent for American media should realize that they are seen as enemies, as a potential hostage for swapping.”

Ditto for pro basketball players like Brittney Griner, who was part of a prisoner swap in 2022.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many Western media companies, such as The New York Times, have evacuated their correspondents from Moscow.

“The few colleagues who stayed — and continued to report on the mobilization, on the growing number of coffins returning from Ukraine, on the escalating crackdowns on any critics of the regime — are inevitably more visible. That could now mean more vulnerable,” Nemtsoya added.

Another journalist for The Atlantic, Tom Nichols, observes, “Americans and their friends in Europe, including among the Russian opposition, have every reason to celebrate today’s releases. But make no mistake: The Kremlin is getting what it wants. And any Westerners who set foot in Russia should always understand that they could be the next bargaining chips for some future deal.”

There has been much talk lately in America about the rise of authoritarianism here and across the globe. In this emerging world, journalists have been branded “enemies of the people.” Business executives and athletes have become new terror collateral.

Despotic leaders can kidnap, poison, imprison and murder their opponents, be they reporters, politicians or critics, both foreign and domestic.

It’s a frightening prospect. It was frightening at the time when I was briefly exposed to these antidemocratic tendencies, and, knowing that this new terror has the potential to spread — even here in America — it is now.

Brian A. Howey is senior writer and columnist for Howey Politics Indiana/State Affairs. Find Howey on Facebook and X @hwypol.

Weekend Read: New school buses arrive spring ’25; schools grapple with bus driver shortages

The Gist Georgia has ordered 256 new school buses to relieve the aging fleets in public schools around the state, but most of those new buses won’t be on the road until the end of this school year. What’s Happening “We’ll be looking at springtime before those buses start rolling,” said Ken Johnson, pupil transportation …

Mega Millions has generated over $17M in HOPE, pre-K funding since June

By now you’re acutely aware you’re not holding the winning ticket to this week’s $810 million Mega Millions Jackpot. That honor goes to a Texan who matched all six numbers. Take solace, though, knowing your weekly spending on lottery tickets in Georgia helps preschoolers get an early educational start and pays students’ way through college …

Presidential race aside, what’s at stake for Georgians in the November election?

The Gist Despite all 236 members of the state House and Senate up for reelection in November, the presidential race has taken center stage in Georgia with the nomination of Vice President Kamala Harris for U.S. president. Nonetheless, Georgia Democrats will be in a push-and-pull contest to gain more seats in both the House and …

Election administrators ‘in limbo’ over new voting rules, top official says

If you plan to hand-deliver your absentee ballot to your local election office this year, you’ll have to show identification and sign a form stating whose ballot you’re dropping off, under a new rule recently passed by the State Election Board. If you fail to show your ID or don’t complete the form, your ballot …