Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoDeKalb CEO Michael Thurmond on Georgia’s labor department, its work-for-Medicaid plan and a possible gubernatorial bid

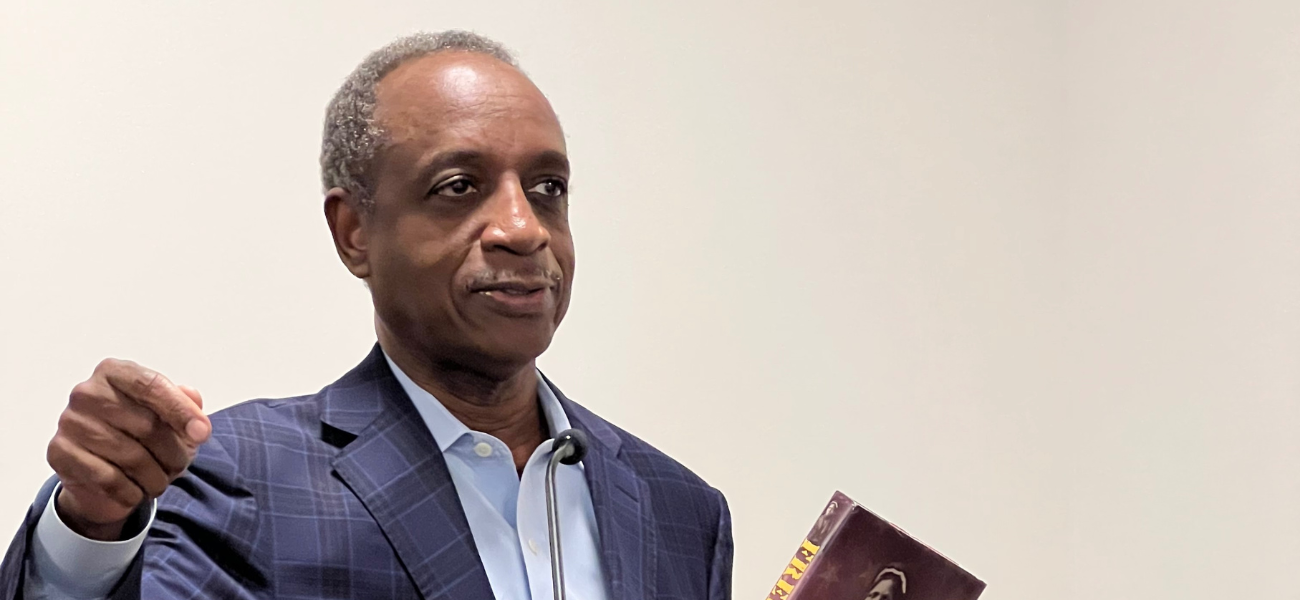

DeKalb CEO Michael Thurmond (Credit: Tammy Joyner)

Michael Thurmond’s work in welfare reform and workforce development has arguably made him the go-to turnaround expert when it comes to fixing government agencies and social programs here and abroad.

In 1994, he was tapped by then-Gov. Zell Miller to transform the culture and operations of Georgia’s Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS). He created the Work First program, which helped more than 90,000 welfare-dependent families move into the Georgia workforce.

As labor commissioner, Thurmond, 70, oversaw a 4,000-employee agency that served via a statewide network of offices he promptly restyled into career centers, doing away with the old-guard term “unemployment office.” As labor commissioner, he was summoned to England to give his advice on workforce development. Other states regularly sought his advice.

During his two years as DeKalb County schools interim superintendent, Thurmond repaired the district’s finances and kept the school system from losing its accreditation while improving student academics and graduation rates.

And when Georgia transformed from a blue to red state in the early- to mid-2000s, Thurmond was the only statewide Democrat to survive the Republican tsunami.

Now as CEO of DeKalb County — the only county in the state with an elected chief executive independent from the legislative branch — Thurmond has a unique perspective on a variety of state-level challenges.

State Affairs caught up with Thurmond, the son of an Athens-area sharecropper as well as a noted historian and author, to ask him about the current state of the labor department, Georgia’s work-for-Medicaid plan and a possible gubernatorial run.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You started your career as an attorney. How did you get into politics and the public service arena?

There was some research I had done on Black history in Athens right after I graduated from [Paine] college [in Augusta]. I ran across a thesis on Antebellum and postbellum Athens. We had two formerly enslaved Black men who had run and been elected to the Georgia House of Representatives during Reconstruction. Their names were Alfred Richardson and Madison Davis. I had no idea they even existed or that Black men had represented Athens. On the way home from the library that day in 1975, I told my sister that I would be the next Black man to be elected to the Legislature from Athens. Eleven years and three campaigns later, I was finally elected in 1986.

The Labor Department seems to be struggling with delayed unemployment benefits and antiquated systems and policies, among other criticisms. The new labor commissioner, Bruce Thompson, has vowed to address the department’s problems. What needs to be done to fix it?

The Labor Department I served as commissioner bears little resemblance to the Labor Department today. It’s a shadow of its former self. It’s just been disassembled. I wish Commissioner Thompson well but I do believe the governor and the Legislature will have to step in and really help to address or reconfigure or reorganize what is now the Georgia Department of Labor. Commissioner Thompson won’t be able to do it. He can obviously improve customer service and some other things but he’s not going to be able to address it by himself. I can just tell you what I know internally: There has to be some external legislative changes made.

You were the architect behind Georgia’s successful Welfare-to-Work program in the 1990s. In July, the state will launch a program that will require eligible Georgians in need of Medicaid health care coverage to work, go to school or volunteer at least 80 hours a month to qualify for coverage. Can a work requirement for medical coverage work?

Each state was able to create its own welfare program. We called ours Work First. Between 1994 and 1997, we successfully transitioned 90,000 DFCS families off of welfare to work.

What we really had was welfare reform without the means. What I learned at DFCS transitioned to the Department of Labor. People need support services. Just to say “Go work” sounds like a good idea but unless you’re willing to create systems and resources that support that, it’s going to fail miserably.

So what we did for welfare reform is we provided transitional Medicaid, transportation assistance. People who wanted to work but didn’t have the skill sets, we contracted with the Department of Technical and Adult Education.

We found that roughly 25%, particularly of the women who were receiving public assistance, had undiagnosed or untreated disabilities. So their employment [situation] was not due to them not wanting to work, or even not just having the skills. They had disabilities that hadn’t been either detected or diagnosed and or treated. So it’s more holistic.

That’s one of the challenges to public service. We want to have one solution that will solve everything and that’s just not true. You have to look at it in a broad context where you look at the nuances that have to be addressed and that fuel success. Our welfare tool was very successful.

If you want to encourage work, you have to address the issues: transportation, training, the basic things. You assume people have resumes. They don’t. It’s almost impossible to get a job if you don’t have a resume. So resume writing and interview skills … Will that be a holistic approach or is that just a political narrative without any real expectation that you will have a major impact on helping people?

Number one, find work and number two, access Medicaid. The economy — if the Federal Reserve is successful — is going into a recession. So that will mean fewer jobs, not more. So how will this strategy compensate for the fact that we’re sailing right into the teeth, according to some economists, of a recession?

Can requiring volunteerism, schooling or employment work, then?

It depends on how it’s structured. I’ve always supported encouraging work. Work has value that extends beyond a paycheck. There’s dignity in work but I also recognize that there must be serious, engaged support and a system to help people who may have been disconnected from the workforce who may not have the skill set or the knowledge or the expertise. There has to be a support mechanism.

Georgia has at least a $6 billion surplus. What should be done with that money?

It obviously needs to be invested in the residents of Georgia to help improve the quality of life, with a particular focus on those who are living at the margins of our society. Metro Atlanta has the worst economic mobility in America. There’s a high probability that if you’re born poor you’ll die poor. If you live in metro Atlanta, that needs to change. I couldn’t think of a better way to invest that money than to break that cycle of poverty, to help people, particularly children, elevate themselves, prepare themselves for a world where they can support themselves and their families and escape the cycle of poverty.

It seems, however, that the focus — at least in the governor’s recent State of the State address — is going to be more on rural areas.

They’re very similar. Just look at census tracts and the pathologies that are impacting rural Georgia. They’re the same ones that have an impact in some urban areas. Oftentimes, poverty is exported from rural to suburban or urban areas. So if you look at it, not just geographically, but the problem themselves that poor families in DeKalb, in some census tracts are having the same problem that rural citizens are having. I grew up poor in rural Georgia. I get it.

At one point you had considered running for governor. Is that still a possibility?

I’m just trying to finish these two years as DeKalb CEO. I’m going into my 70th year and one of the things [I want to do] is just finish strong. The future will take care of itself.

So is that a yes or no?

(He chuckles). I gotta stay focused. DeKalb is no joke. I’ve enjoyed being the CEO of DeKalb. We’ve made a tremendous amount of progress. I just want to close the deal and think about tomorrow tomorrow.

Looking back on your career, is there anything you would do differently?

Enjoy life more early on, when I was getting started. I was just so afraid that I was going to fail. My friends, family members and others have encouraged me to kind of smell the roses a little bit. So now that I’m on the back end of this, they were probably right. I could have enjoyed life a little bit more, travel more and some things that I like, but I didn’t. So I tell my daughter that now. She’s got my psychological profile. But I encourage her to enjoy life a little more while she’s young and can truly benefit from it.

What led to your decision to write books on Georgia history? What is the biggest takeaway from the two books you’ve written so far?

Well, my dad bought a set of encyclopedias back in the early 60s and that was just like having a computer in a house. We didn’t have the other conveniences but we had a set of encyclopedias. My favorite one was the letter G for Georgia. I just started reading and it was just one or two things about Black people in the G for Georgia [volume]. So it just began there. I love Georgia history.

The most important takeaway is that we should not paint history with a broad brush, particularly as it relates to the era of slavery, after enslaved Blacks along with white and Native American allies fought valiantly and courageously against the system of chattel slavery. What’s not told is that thousands earned their freedom successfully during that period of enslavement in Georgia.

You’re working on another book. What is it about?

It’s an extension of research. I’m generally interested in the founding of Georgia, 1733 to 1865. This book looks more closely at James Oglethorpe, the father of Georgia, and how his relationship with formerly enslaved Black men helped to shape the prehistory of the abolitionist movement.

If confined to your home for a week, what food would be a must-have?

My wife Zola’s peach cobbler. She makes it from scratch. It’s not written down.

The Michael Thurmond File

- Title: CEO of DeKalb County

- Age: 70

- Birthplace: Athens, Ga.

- Residence: Stone Mountain

- Education: Graduated cum laude with a bachelor of arts degree in philosophy and religion, 1975, Paine College; graduated from University of South Carolina Law School, 1978; completed the Political Executives Program at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

- Career: Attorney; became the first Black since Reconstruction to be elected to the Georgia General Assembly from Clarke County, 1986; selected by then-Gov. Zell Miller to head the state’s transition from welfare to work, 1994; became a distinguished lecturer at the University of Georgia’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government, 1997; elected Georgia labor commissioner, 1998; superintendent of DeKalb County Schools, 2013-2015; elected CEO of DeKalb County, 2016.

- Hobbies: Writing and researching.

- Accomplishments: Written two books: “A Story Untold: Black Men and Women in Athens History” and “Freedom: Georgia’s Anti-Slavery Heritage 1733-1865.”

- Family: Married to Zola; one daughter, Mikaya

- What job would you want to be doing other than your current one: I’d be president of Paine College in Augusta.

You can reach Tammy Joyner on Twitter @lvjoyner or at [email protected]. Joyner is State Affairs’ senior investigative reporter in Georgia. A Georgia transplant, she has lived in the Peach State for nearly 29 years.

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA | @STATEAFFAIRSIN

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS | @STATEAFFAIRSIN

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA | @STATEAFFAIRSIN

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header image: DeKalb CEO Michael Thurmond (Credit: Tammy Joyner)

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …

2 young Democrats win Statehouse seats as Republicans hold majority

ATLANTA — Many Statehouse incumbents appeared to beat back challengers Tuesday, ensuring their return to the Capitol in January. Republicans retain control of the House and Senate. Two Generation Z candidates will join the 236-member Legislature as new members of the House of Representatives: Democrats Bryce Berry and Gabriel Sanchez. Berry, a 22-year-old Atlanta middle …