Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoIEDC board members’ companies benefit from millions of dollars worth of tax breaks and incentives

Ground breaking for Eli Lilly development in Lebanon. (Credit: Gov. Eric Holcomb/Flickr)

Editor’s note: This article is part one in a State Affairs and Fox59/CBS4 series looking at how decisions get made at the Indiana Economic Development Corp. and how it impacts economic development in the state. The IEDC has faced increased scrutiny due to its involvement with Boone County’s LEAP Lebanon Innovation District and because two gubernatorial candidates are former IEDC leaders.

State leaders celebrated when they announced Eli Lilly and Company’s expanded plans for research and manufacturing facilities in Boone County’s LEAP Lebanon Innovation District, expected to generate 700 jobs and $3.7 billion worth of capital investment.

But the unprecedented investment also came with an unprecedented price tag for the state.

The Indiana Economic Development Corp., the state agency tasked with luring businesses to Indiana, agreed to supply Eli Lilly with up to an estimated $378 million-worth of tax credits, rebates and site readiness assistance for the LEAP District project. To put that into context: That’s more than what the state will spend on new public and mental health initiatives for all Hoosiers over the next two years.

So who approves these massive deals? In this case, it was a committee of the IEDC’s appointed governing board that gave the final OK on the state’s largest incentive package to date. The IEDC’s 14-member governing board has deep ties to the business community, and one of its members was chairman of Eli Lilly’s board of directors as recently as 2017. (The IEDC says he did not have a financial conflict of interest, nor was he on the committee that voted.)

The Indiana Economic Development Corp. has doled out tens of millions of dollars worth of tax incentives and grants to companies linked to its governing board members, a State Affairs and Fox59 analysis found. While individual board members appear to have recused themselves from voting on those contracts, their peers on the board do.

That’s the challenge of a state economic development agency: Those with the most expertise to lead such an agency are typically people still in the business world.

The reliance on business industry leaders to decide which companies should receive state dollars and tax breaks is problematic, said Julia Vaughn, executive director of the government accountability group Common Cause Indiana.

“I think the structure creates a real problem in terms of ethics and board member involvement in key decision making,” Vaughn said. “You’re creating conflicts of interest if you have board members who are going to be eligible for state dollars.”

New Secretary of Commerce David Rosenberg declined an interview request through a spokesperson, but the IEDC — which Rosenberg heads — answered multiple questions about how its leaders avoid conflicts of interests among board members.

“Because the IEDC is tasked with growing the state’s economy, the governor appoints board members who have significant private sector experience and are experts in their respective industries,” Erin Sweitzer, an IEDC spokeswoman, said in an emailed statement. “There is nothing that prohibits the companies with which our board members are associated from applying for and receiving performance-based incentives from the state, following the state process as any other business, provided that they have no role in the IEDC’s decision-making process regarding that contract.”

Impact on taxpayers

Money for some incentives come from the state’s general fund, the same taxpayer-funded bucket of cash that pays for schools, public safety or other services for Hoosiers. The rest of the incentives come in the form of tax breaks given to companies, meaning those companies relinquish a smaller portion of their earnings to the state.

That’s why Sen. Fady Qaddoura, a Democratic member of the State Budget Committee, thinks it should matter to Hoosiers how tax credits and grants are distributed.

“[The IEDC is] spending taxpayer dollars cutting deals day in, day out with very little level of transparency or oversight,” Qaddoura said. “That billion plus dollars that the taxpayers have funded could have gone to their local schools, could have expanded child care or pre-K, could have paved our streets, could have reduced their taxes or fees imposed by government.”

Qaddora emphasized that economic development initiatives aren’t inherently bad if they’re done right.

To that point, proponents of economic development incentives say the tax credits doled out to companies generate economic development and more high-wage job opportunities for Hoosiers. In fact, a report on 2021 job creation numbers from the IEDC shows that the state collected more in income taxes from the new jobs than the state spent on tax credits and grants.

In Gov. Eric Holcomb’s opinion, the state is winning because of the IEDC.

“I think what separates IEDC from some of our competition … is that our board is members of the private sector who are scattered across the whole state of Indiana,” Holcomb said following the IEDC’s quarterly meeting in Goshen in September. “They represent regions, ecosystems, industries, sectors, and they come from the private sector. They get it.”

Rules surrounding disclosures

Before the IEDC economic development deals were handled internally by employees at the Department of Commerce. That changed in 2005 when then Gov. Mitch Daniels created the IEDC and a board to govern it.

Typically low-dollar projects don’t need approval by the board, while those with a higher price tag are approved at the committee level. But when a potential conflict of interest is present, the deal is supposed to go to the full board for approval, according to IEDC rules.

Indiana law requires nearly every state employee and appointee to abstain from participating in any decision or vote if that person has a financial interest in the outcome. They also are required to publicly notify the Ethics Commission of potential conflicts of interest each time one arises before contracts are awarded.

But, since at least 2013, IEDC board members haven’t had to completely follow those disclosure rules. They’re allowed to disclose potential conflicts long after contracts have been awarded, in order to avoid disclosing information on not-yet-public projects. Projects instead are assigned vague names when they’re voted on, such as “Project Grasslands” or “Project Amuse Bouches.” Vaughn said that type of notification is “a little too late.”

“The decisions have already been made,” she said.

Whatsmore, even when the beneficiaries of contracts have already been publicized, the IEDC appears to file conflict of interest disclosures well after the board votes.

At its September 2023 meeting, the IEDC board approved a $1 million tax break for Indianapolis-based Scale Computing. Thompson recused himself, sharing that he’s an investor but more than a month later there’s still no disclosure posted on the inspector general’s website.

“Conflict of interest disclosures are filed with the inspector general in due course, and the John Thompson disclosure you referenced will be reflected in our next filing,” Sweitzer said in an email.

Attempts to reach Thompson directly were unsuccessful.

State Affairs and Fox59 found multiple projects since the IEDC’s 2005 creation in which there was no conflict of interest form or formal opinion from the Ethics Commission posted on the state’s website.

Most of those projects were under previous administrations or occurred prior to a 2016 ethics policy change in which the IEDC tightened some of its rules. The IEDC declined to weigh in on why paperwork was sometimes not filed under previous IEDC leaders.

How board members’ companies benefit

It’s common for board members to recuse themselves due to potential conflicts of interest. At the four board meetings in 2018, there were six projects in which at least one board member had to recuse him or herself due to potential business ties to a project.

Since 2015 when lawmakers updated state ethics laws, board members filed conflict of interest disclosures for 32 scenarios. Some of those documents disclosed indirect benefits, such as the IEDC awarding a tax credit to a project financed by a bank a board member leads; or an entity a board member’s company regularly works with.

For example, in 2017 Mark Miles, president and chief executive officer of the organization that operates the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Indycar, recused himself during a vote on a $900,000 grant to help Dallara USA Holdings Inc. develop a new racecar component for an IndyCar racing team.

Miles said he never talked to any fellow board member about a conflict on any agenda that could have financially impacted him, nor did any board member talk to him about projects that might have benefited them.

“I’m not sure who you would want to make judgments about incentives and programs for businesses that would have more insight than business people,” Miles said. “I just know [board members] to be people of integrity, who have not individually, or for their companies, profited to my knowledge, and I think they have acted in the best interest of the taxpayers.”

There were other more direct financial benefits that did not show up on those conflict of interest disclosures, because they occurred prior to 2015. There was also no formal opinion from the Ethics Commission posted online, a state requirement prior to the 2015 law change.

The late-Dane Miller, co-founder of Biomet Inc., recused himself when his peers approved projects benefiting his company in 2006 and 2010, worth up to a collective $4.8 million in tax credits.

Likewise between 2005-2010, the IEDC awarded Columbus-based Cummins at least $20 million worth of tax credits for economic development projects. A Cummins executive was on the IEDC board during that window, both recusing themselves when a Cummins project came up for a vote. Attempts to reach either were unsuccessful.

And in 2009, the late-William Mays signed a contract worth up to $48,500 with the IEDC on behalf of his company Mays Chemical Company while serving on the IEDC board. Meeting minutes provide no indication that the board voted on this contract.

Aside from simply following the ethics rules, Vaughn said conflicts could be avoided if governors simply appoint different people to the board. Right now, board members include bank executives, the chief executive officer of Indianapolis Motor Speedway, a former Eli Lilly head and the co-founder of Fair Oaks Farms.

“Perhaps there’s just a real problem as to the pool of people they’re bringing in,” Vaughn said. “It would be better if they found folks that certainly were experts on the topic, but not eligible to receive this state money. The entire process seems to be set up to make it hard to avoid conflicts of interest.”

Watch the broadcast on Fox 59’s YouTube channel.

Contact Kaitlin Lange on X @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Know the most important news affecting Indiana

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

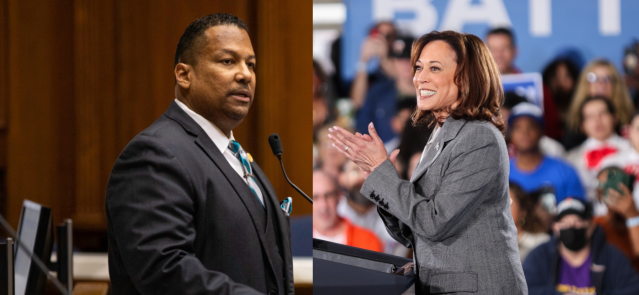

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …