Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoRepublicans pitched big ideas to fix mental and public health, and here’s where they ended up.

Indiana Senate Majority Whip Sen. Michael Crider, R-Greenfield, addresses Senate during deliberations April 25, 2023. (Credit: Mark Curry)

- Advocates received half of what they wanted for mental health purposes.

- Holcomb admin says about half the state will be served by mental health crisis system.

- Sen. Ed Charbonneau blamed the shortfall in public health funding on a distrust of the state health department following the pandemic.

Sen. Michael Crider spent months advocating for a boost of at least $100 million per year to transform Indiana’s struggling mental health system.

The Greenfield Republican’s companion bill to the state budget garnered nearly unanimous support and earned the coveted Senate Bill 1 spot, usually reserved for Senate Republicans’ top priority. Then in the thick of state budget negotiations last month, House and Senate leaders learned some unexpected news: Updated revenue forecasts revealed they had access to an extra $1.5 billion over the next two years.

The surprise money could have paid for Crider’s mental health request for more than a decade. But Crider wasn’t celebrating.

With the news, he could already guess that no one would support a cell phone fee to pay for the mental health system overhaul at a time of excess revenues. His pitch for a fee was dead, and so was his chance at exceeding $100 million per year for mental health.

“When the budget forecast came out, you could just kind of feel that disappearing,” Crider told State Affairs last month. “I think I may be one of the few people in the state who was disappointed when we had a surplus because I think that sealed the deal for me probably.”

This year’s legislative session showed how even bills with widespread, bipartisan support can fail to achieve full financial backing in a fiscally conservative legislature that typically prefers a more measured approach. It was even true when Republicans, who hold a supermajority in both chambers, targeted their priority legislation to address Indiana’s abysmal numbers for suicides, overdoses and public health outcomes.

Part of the challenge was the number of health-related problems they were trying to solve at once. As Crider fought for at least $200 million over the next two years, his colleague Sen. Ed Charbonneau, R-Valparaiso, sought an even higher amount for public health: $347 million.

By the end, Crider received half his request. Charbonneau received about 75% of his.

While both numbers fell short, both senators — and many advocates — were still thrilled to see the Indiana General Assembly take significant steps to address their concerns.

“I’ve spent more time laying awake at night thinking about this and what I could have done and honestly, while I’m disappointed, I’m at peace,” Crider said. “I was trying to hit it to the fence. I got to second base. That’s great progress. Most people aren’t going to get that done.”

Mental health receives less than half estimated need

Back in January, Senate Republicans started outlining their plans to tackle some of the state’s most significant and nagging challenges.

Suicides here have remained above the national average, and drug overdoses grew by more than 100% over 10 years, according to an analysis by an Indiana demographer.

The nonprofit Mental Health America last year said Indiana ranked 42nd in treatment.

So Crider carried Senate Bill 1. The goal? Follow up on creating the 988 crisis hotline by expanding it into a three-part system. The other two parts would include mobile crisis teams to respond to calls for help and crisis stabilization units where people can go for up to 23 hours at a time to receive care.

The system would ideally work like 911 but for someone experiencing a mental health crisis, whether that’s driven by suicidal thoughts, drug addiction or another issue.

Fully funding the crisis system would cost roughly $130 million per year, according to an estimate by the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA).

But with only $50 million per year allotted in the budget, an FSSA spokeswoman told State Affairs that about half of the state will be covered.

While that fell short of advocates’ ambitions, it’s still a dramatic improvement over what had been planned as a modest expansion at the start of this year by relying on federal dollars.

“The Indiana mental health advocacy community led the charge this legislative session for bold, transformational changes to Indiana’s system,” said Jay Chaudhary, director of FSSA’s Division of Mental Health and Addiction, in a statement. “Our goal over the next two years is to match their sense of urgency and use this substantial investment to lay the foundation for a system that works for Hoosiers, both now and in the future.”

The FSSA is aiming for statewide coverage by 2027, according to its spokeswoman.

Some community mental health centers, meanwhile, have already started rolling out the three-part crisis system.

Early data shows a lot of promise. At 4C Health in Logansport, for example, mobile crisis teams since September 2020 have responded to more than 3,000 calls for help across four largely rural communities.

The teams are able to stabilize someone in crisis about 65% of the time, according to 4C Health, which allows that person to remain safe at home. The crisis stabilization unit, meanwhile, has led to a 24% drop in admissions to the costlier psychiatric facility, amounting to more than $1 million in savings.

Some Indiana centers are also relying on temporary federal grants to fund their transition into a new treatment model called certified community behavioral health clinics (CCBHC), which provides a greater range of services.

Another goal of Crider’s legislation is to move all mental health centers into the new model.

That will require the state to apply for what’s called a demonstration program. Ten states participate, and providers and advocates previously believed that Indiana had been rejected by the federal government for consideration.

Then the FSSA received clarification in March that Indiana remained in the running. If approved, mental health providers would receive greater Medicaid reimbursements, which would allow them to provide even more services beyond the three-part crisis system.

Will the public health money be enough?

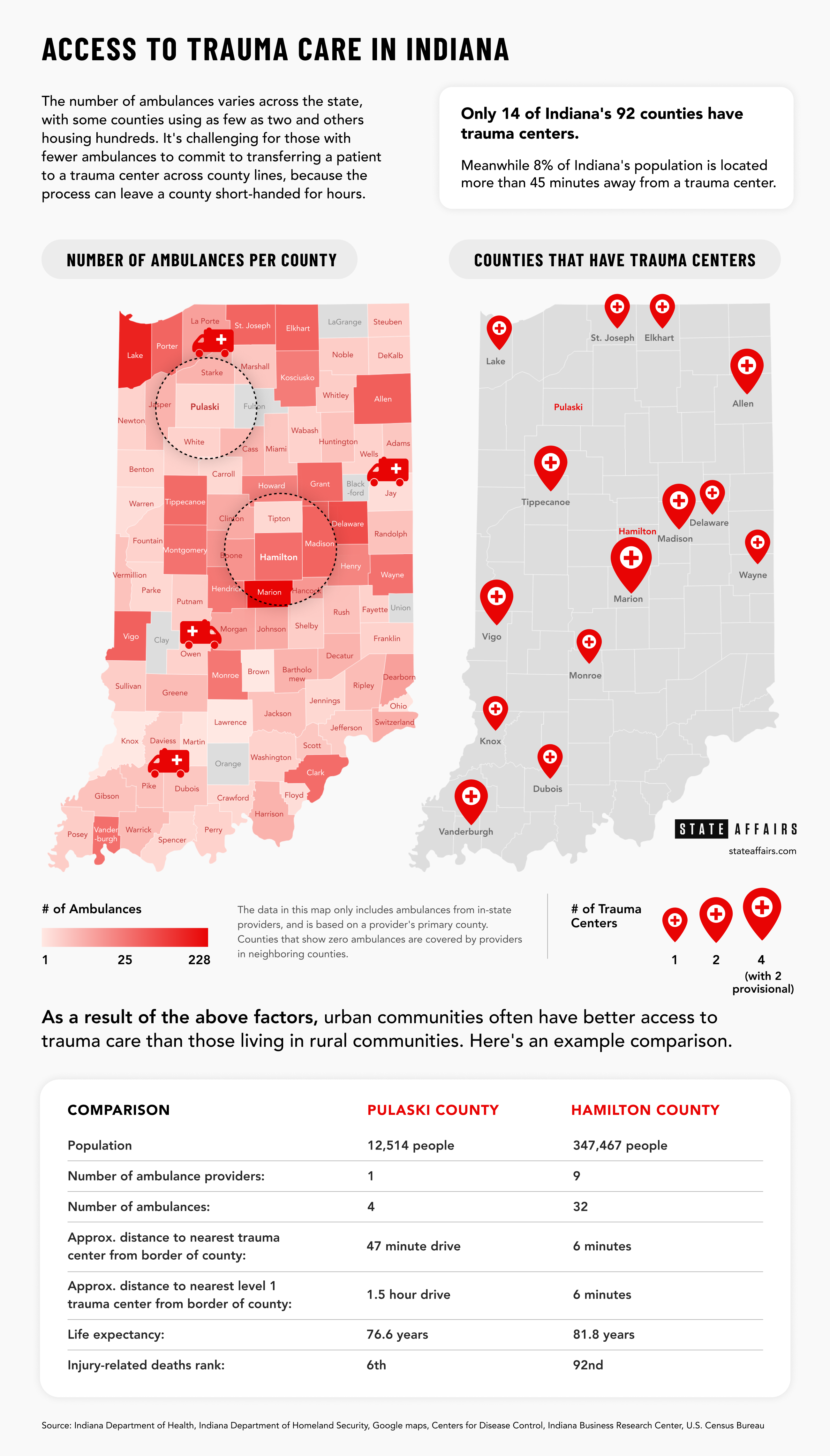

Health experts were looking at similarly dismal physical health statistics at the start of session, which Gov. Eric Holcomb’s administration surmised was due to a lack of funding for public health and trauma care.

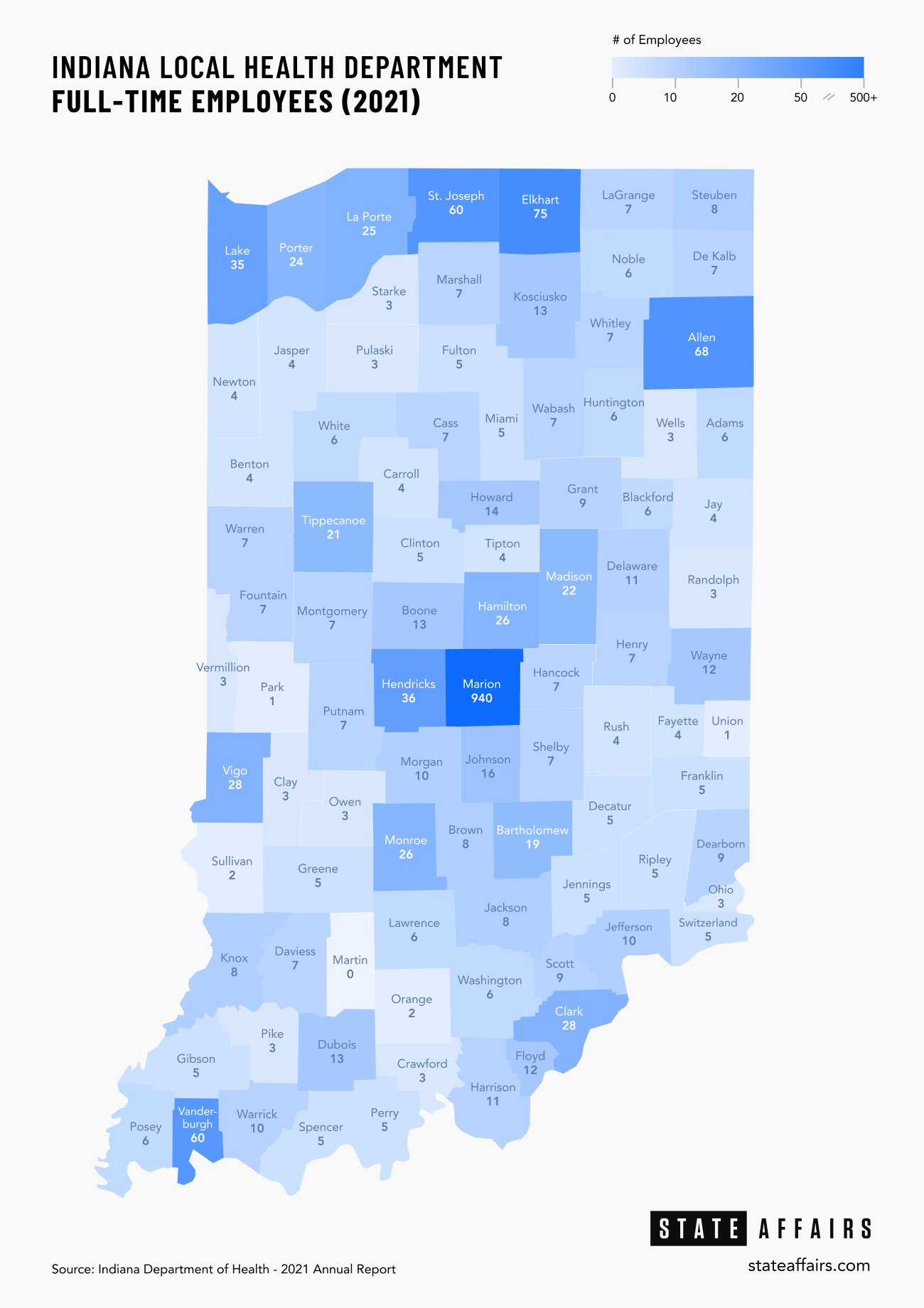

The final budget contained about three-quarters of Holcomb’s initial $347 million ask. Specifically, over the next biennium, state lawmakers budgeted $225 for local health departments that decide to opt into receiving the state public health funding in exchange for matching a portion of the dollars locally.

The idea is that local health departments can use that extra money for services such as implementing more tobacco cessation programs for those struggling to quit smoking, offering free immunizations for children, or providing HIV testing.

In Ripley County, for example, County Health Officer Dr. David Welsh said leaders might use the money to up salaries in an attempt to quit hemorrhaging health department employees who provide valuable services, such as septic tank inspections.

The budget also contained additional dollars for improving the state’s trauma care system and money for the state health department to build up support for local health departments. The goal is to eventually build out the trauma care system so that all Hoosiers are located within 45 minutes of a trauma center.

“Once you add it all up, it’s huge,” Holcomb said. “It allows us to get started building, not just the relationships — we’ve established those in all of these local communities, but it allows us to start working with folks who want to participate.”

But while the investment dramatically expanded public health funding, some advocates were hoping for more. Before the pandemic, Indiana only spent $55 per capita on public funding, compared to the U.S. average of $91, according to a report from the Governor’s Public Health Commission, leading to disparities in public health access.

Whether or not this extra money will be enough to reduce the gaps in public health access will largely depend on how many counties choose to take money from the state. Counties have until Sept. 1 to opt in to the first round of funding, which will be awarded in January based on how many choose to participate.

“I’m going to accept what we can get at this point in time,” Charbonneau said. “Certainly, I would love to get 100% of the funding that we started with but that’s not in the cards, but I think with where we are with the funding we’re going to be able to get a lot done.”

Why lawmakers didn’t dedicate more money

It wasn’t a lack of resources that held back legislative leaders from providing more funding to mental and public health. It was a combination of political will and a hesitancy to spend big all at once.

And maybe some skepticism about how much money is actually necessary. For example, if a majority of counties don’t seek the increased funding for public health, why dedicate so much money to it?

“The tough thing around here is nothing is ever fully funded,” said House Speaker Todd Huston while speaking from the House floor about the final budget. “When you ask people what would it take to be fully funded, the answer is always the same: Just a little bit more.”

Efforts to increase public health funding were hindered by a fear among some conservatives that doing so was the equivalent of giving the state health department more power. That’s an uncomfortable idea for those who felt Holcomb and his administration went too far when addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

“There’s a lot of misconception, apprehension, because the pandemic created some problems in the minds of folks,” Charbonneau said. “We need to get beyond those, and I think the only way to get beyond them is to start doing something.”

Perhaps nothing illustrated the tension better than this: In the end, 31 Republicans voted against Senate Bill 4. It’s uncommon to see that many Republicans vote against a Republican priority bill.

For the mental health legislation, collecting votes proved to be a lot easier. It was harder, though, to convince budget writers to open the state’s checkbook.

President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, said earlier this year that he prefers incremental increases in spending when possible. And on the last day of the legislative session, Bray acknowledged that some would be disappointed with the final budgeted amount.

“I know Senator Crider and some other advocates wanted significantly more than that,” Bray said. “But it’s a really good, productive start.”

Among the loudest voices supporting Crider’s legislation was Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, who shared personal testimony about mental health struggles within her family. She had advocated for the full $130 million per year, too.

But she told State Affairs that she’s happy with the budget.

“Would I have loved to have had more? Of course, we all would love to have more,” said Crouch, who is also campaigning to become the next governor. “But that $50 million a year — with what we’re going to be able to combine with the federal funding — will allow us to really start doing some great things for Hoosiers in mental health and addiction.”

Demonstrating the value

Public and mental health advocates are hopeful they’ll be able to cobble together more funding in two years when the next budget is crafted, but that’s only if they can demonstrate a continued need.

In some ways getting this year’s budget passed was the easy part when it comes to overhauling the public health system. Now advocates must convince local elected leaders — some of whom have no health background — to accept the state dollars and commit to following basic guidelines for how to use the money.

If they can prove enough counties are interested, they might be able to justify increasing the funding in future years.

“It’s not enough to just make the basketball team,” said Welsh, who is also the health officer for Franklin County. “You want to win state.”

Welsh was a member of the Governor’s Public Health Commission, but even he remained skeptical that the elected leaders in both of his counties would accept the funding during the first year. Welsh used another sports analogy to explain why some counties might wait.

“At the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, every time there was a new engine or new car that came on the scene for Indianapolis, everybody didn’t jump in,” Welsh said. “They’re like OK, let that team try it first and we’ll make sure it works.”

Likewise, 4C Health CEO Carrie Cadwell said it’s on her and other mental health providers to prove to state lawmakers that their funding will pay off in improved mental health outcomes.

“This kind of investment is unprecedented, even at $50 million a year,” Cadwell said. “Now it’s time for those of us who are doing the work — of crisis stabilization, mobile crisis, community mental health centers — to step to the plate to demonstrate what that $50 million can do and what further investments down the road can do.”

In the meantime, 4C Health expanded to three more counties this week.

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: Indiana Senate Majority Whip Sen. Michael Crider, R-Greenfield, addresses the Senate during deliberations on April 25, 2023. (Credit: Mark Curry)

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …