Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoIndiana’s state-funded pre-K is expanding, but there are still significant barriers to access.

Teacher Katie Krevda interacts with students during a free play period in her pre-kindergarten class at Westview Elementary School in Jonesboro, Ind., on Tuesday, April 10, 2018. (Credit: Jeff Morehead/The Chronicle-Tribune via AP)

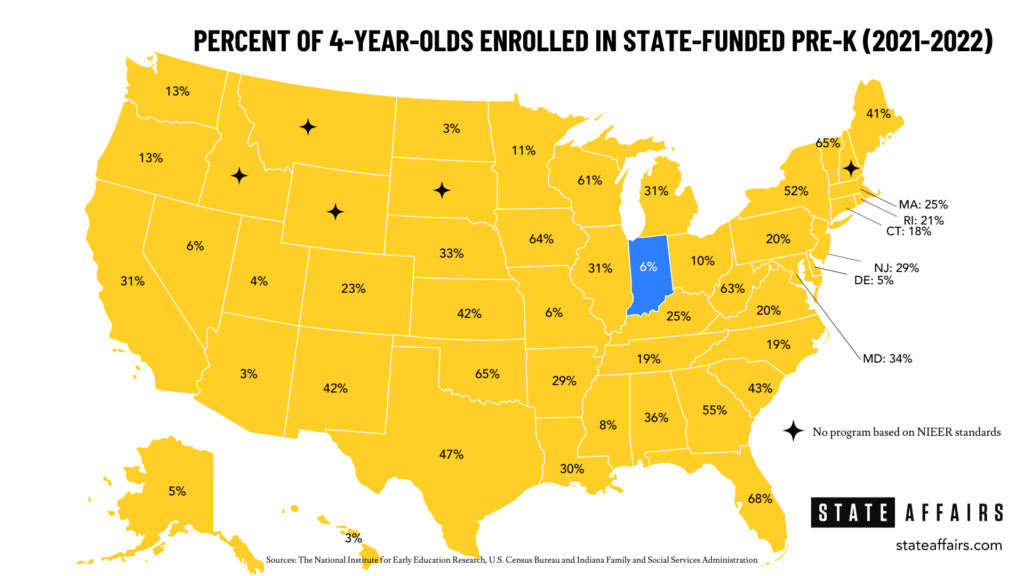

- At least 36 other states provided state-funded pre-K for a higher percentage of 4-year-olds in the 2021-2022 school year.

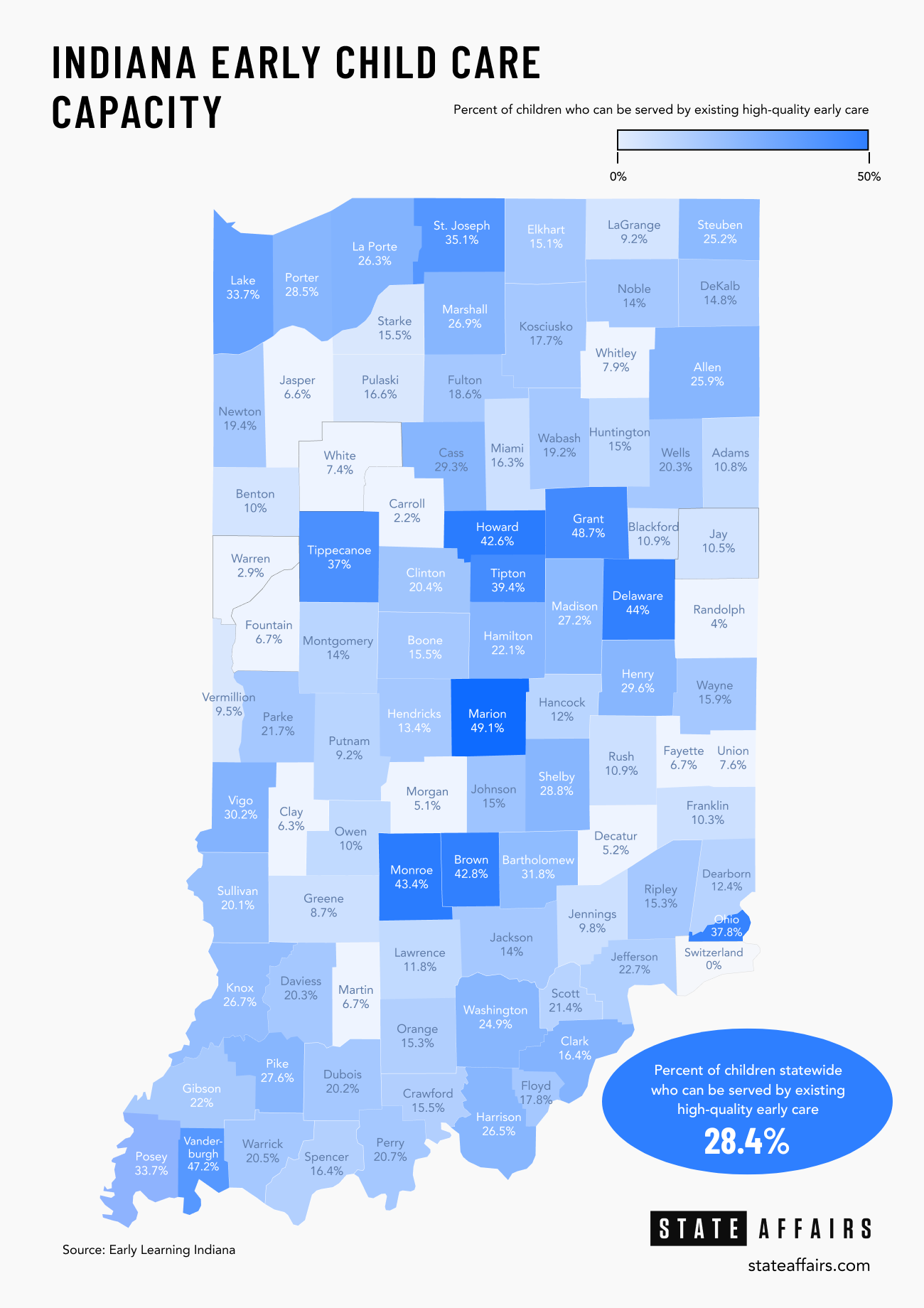

- Three quarters of Indiana’s counties are only able to serve at best half of the children who need early child care or education due to capacity shortages.

- At least 10 counties do not have a provider that accepts children using state preschool grants listed on the state’s child care-finder portal.

As students start pre-K this month, a family of four making $45,000 or less per year will be able to access free, state-funded preschool.

That means an average family down in Crawford County likely would qualify. The 10,000-person southern Indiana county has a median household income of less than $43,000 — almost $20,000 lower than the state’s median — and below the eligibility requirement for the program.

But, no preschool provider in Crawford County is considered high quality enough to accept those state dollars for pre-K.

Most parents will either have to dish out thousands of dollars for child care themselves, keep their child at home or spend valuable time traveling to a different county.

“Some of our kiddos might still be coming if half their bill had been paid, and yet we’re in a predicament, too, because we’re barely making ends meet,” said Kim Grizzel, executive director of the the Boys & Girls Club of Harrison-Crawford Counties. “We have to have them pay their bills because we have to pay our employees, so it’s a hard spot to be in.”

Whatsmore, even if a family can afford the costs of early child care or pre-K without a state grant, a report from Early Learning Indiana shows the county only has enough early learning and care capacity for roughly one in six children living there.

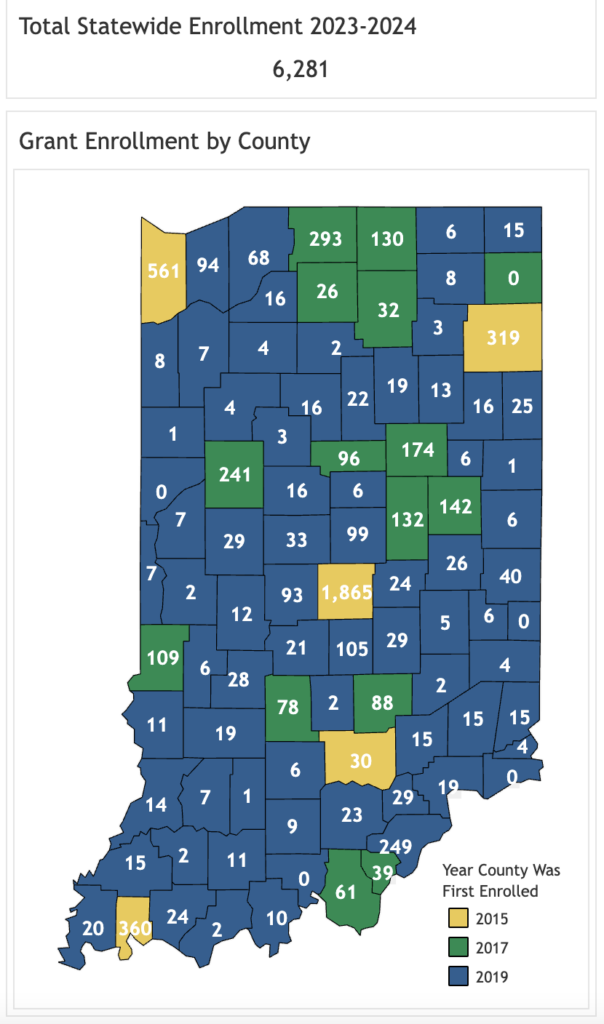

Crawford County illustrates the problems that still plague the On My Way Pre-K state grant program in it’s ninth year, even as advocates are praising state lawmakers for what they view as major advancements in the early education space during the most recent legislative session. Lawmakers raised the household income eligibility from $38,000 to $45,000 for a family of four with a 4-year-old child, or 150% of the federal poverty rate. Enrollment for the 2023-2024 school year has already surpassed that of 2022-2023.

Children who participate in On My Way Pre-K have better language and literacy skills and are more ready for kindergarten than their peers from similar financial backgrounds, a report from the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA) shows.

But most Indiana children will never benefit directly from the state-funded program. Indiana’s state-funded pre-K program still serves a smaller percentage of children than a majority of other states, which contributes to a broader affordability problem in the state. Last school year 16 counties had two children or fewer use a grant for state-funded pre-K, and State Affairs counted at least 10 counties with no providers who qualify to accept grant-funded children listed on the state’s child care-finder portal.

There’s also a shortage of quality early child care providers and seats throughout Indiana, meaning even if someone can afford pre-K, in some counties there’s a waitlist. In fact, when CNBC ranked Indiana as one of the 10 worst states to live and work last month, the news organization attributed the ranking largely to a lack of licensed child care facilities.

While the Republican-dominated Indiana Legislature has grown more open to the idea of state-funded pre-K over the years, they’re still not rushing to offer it to anyone but the poorest Hoosiers, even as leaders lament the need to fix some of Indiana’s dismal educational outcomes.

The result: Where you live and how much you make still dictates what kind of access your child has to quality pre-K and in part their educational outcomes. The benefits of access to quality pre-K can also extend to the whole society, advocates say.

“By investing in children, we’re also investing in the adults in their life … enabling mom and dad or grandma or grandpa, whoever their adult caregiver is, to have opportunities to work productively or to attend higher education or other kinds of training opportunities,” said Sam Snideman, vice president of government relations for United Way of Central Indiana. “We’ve put adult and child on the path toward hopefully a higher level of economic stability and security.”

Shifting mindset on pre-K

Part of the challenges to a quality pre-K system stem from a lack of political will among lawmakers to allocate more money in the budget each year toward pre-K grants. Some conservatives are leery of most universal programs amid concern about ballooning costs of government welfare initiatives.

Whatsmore, in the budget making process, there’s no shortage of groups asking for more state dollars, and there’s only so much to go around. In the House, Republicans often prefer to leave a large enough cushion to cut certain taxes. They’ve also focused on expanding the K-12 school choice voucher program so that a family making up to $220,000 can receive state dollars to send their child to a K-12 private school or another school of their choice. Across the aisle, Senate Republicans are more focused on paying down debt to free up money in future years.

Still, leaders in both chambers and Gov. Eric Holcomb included at least some expansion of eligibility in their proposed statewide budgets this past legislative session with little resistance.

That in itself signals a shift over the last decade. When then-Gov. Mike Pence signed Indiana’s On My Way Pre-K pilot program into law in 2014, the concept of state-paid preschool was more controversial in Indiana. The final version of the program that became law only served a handful of counties as a pilot program, but even then it almost didn’t cross the finish line due to skepticism among Republican lawmakers. Since then, the program has grown and is now available to providers across the entire state.

Even so, Republicans on the Senate Appropriations committee voted against an amendment to the budget during the legislative session to expand pre-K eligibility to 400% of the federal poverty line — closer to the level that the state’s K-12 school choice voucher system was expanded to. Only Sen. Chris Garten, R-Charlestown, explained his no vote, saying there was a “math issue within the budget.”

Other Republicans have indicated a desire to keep the program more focused.

“Our goal is to reach more low-income families and continue to grow the number of quality providers across the state,” Republican Rep. Bob Behning, chair of the House Education Committee, said in a statement.

Richmond Republican Sen. Jeff Raatz, the chair of the Senate education committee, said there’s still too many outstanding questions to entertain a complete expansion of the program right now. For example, FSSA isn’t using up all of the money budgeted for the program each year, a problem that may be at least partially remedied by the expansion of eligibility lawmakers just approved.

He’d like to determine why the program is not more popular. FSSA told State Affairs it doesn’t track how many students should qualify for the program and just don’t take advantage of it.

After that, it comes down to voters and what’s fiscally realistic, Raatz said.

“Does the citizenry of the state that have children want it; and two, does the state have the resources that we can red-line for this endeavor?” Raatz asked. “That’s a future conversation.”

The affordability problem

Other states are able to increase early education affordability at least in-part by dedicating more state resources to pre-K. At least 36 other states served a higher percentage of 4-year-olds in the 2021-2022 school year, based on data from both the state and the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER).

In 2022-2023, a little over 7% of Indiana’s 4-year-olds were enrolled in On My Way Pre-K, meaning Indiana likely won’t advance much in the rankings.

It’s not just liberal states that are offering universal pre-K to those who want to participate. Florida and Oklahoma, two now ruby-red states where Republicans control both chambers, topped the list, both providing pre-K for more than 65% of their 4-year-olds during the 2021-2022 school year. Oklahoma specifically, a state that hasn’t voted for a Democratic presidential candidate since the 1960s, is seen as a model, having tucked its pre-K funding into its K-12 funding formula.

Indiana differs from a majority of other states in other ways too: Indiana only offers grants to 4-year-olds and eligibility hinges on a child’s guardian working, going to school or actively searching for a job.

Of course, the limited eligibility isn’t the only reason why Indiana’s participant count has been low. FSSA says it’s challenging to get people to complete their applications, and in some counties there just aren’t enough high-quality options. COVID-19 also likely impacted demand, a spokesperson for FSSA said.

With fewer grants in use, that makes Indiana’s pre-K less affordable overall. In 2021, families on average likely spent around 15% of their gross annual income on preschool or other early care for one child, according to Early Learning Indiana.

Once again, how much of a person’s salary is spent on child care differs by county, with someone in Madison County spending more than 16% compared to just under 6% in Union County.

Snideman suggested that even expanding the eligibility requirement to include those making up to 185% of the federal poverty rate would open doors, but keeps Indiana far from a more controversial universal program.

“Many low income and working class families aren’t able to find affordable child care options,” Snideman said. “By putting more money into the system, putting more money in the hands of families, you’re able to empower them to access opportunities that middle and upper income families have always been able to access.”

Capacity struggles

A shortage of early child care providers also strains Indiana’s efforts to get the state’s youngest residents a good start to their educational journey. It’s perhaps a less controversial problem, but one that is more challenging to solve.

Early Learning Indiana estimates that four out of every 10 young Hoosier children don’t have a preschool or early child care seat in Indiana, and only a little more than a quarter of children can be served by a high-quality early learning opportunity.

And that may be a rosier picture than reality. Those numbers are based on how many seats a child care facility is licensed for, not how many they actually can teach based on their current employee count.

Actual capacity is more limited, exacerbated by challenges attracting and retaining employees.

Half of center-based providers and one fifth of home-based providers who responded to a November 2021 survey from Early Learning Indiana said they had to reduce their capacity due to workforce problems. That accounted for a loss of 7,700 seats.

In reality, that means roughly three quarters of Indiana’s counties likely are only able to serve at best half of the children who need some sort of early child care.

“It very much depends community by community,” said Maureen Weber, Early Learning Indiana president and CEO, “and if you look holistically across the state, we might have sufficient access but that doesn’t mean that an individual in a rural community can go access the seat that he or she wants.”

In Crawford County, the Boys & Girls Club is short six staff members. Grizzel also said workforce dilemmas mean she can’t hire the number of credentialed employees she would need to qualify for the state pre-K dollars.

“We don’t have that kind of pool of people around here,” Grizzel said.

Early Learning Indiana, which also provides preschool, toddler and infant care for about 1,200 children in Tippecanoe and Marion counties, had to reduce its seats by 20% due to a staff shortage. That’s the reality of an economic climate with low unemployment rates, Weber said. People can choose to work at Amazon or FedEx where the wages are more competitive.

Snideman emphasized that if an organization with more resources such as Early Learning Indiana is struggling with attracting talent, it doesn’t bode well for the rest of the system.

“Our interests in balancing access and affordability can’t come at the expense of the workforce that supports the whole system,” Snideman said. “It’s really difficult to incentivize anyone to work in a child care center for $9 an hour, and in order to keep costs relatively low for families, if you’re a provider you don’t have a lot of choice on where you can find savings to keep your price point affordable.”

Advocates also have concerns about the pending cliff of federal COVID-19 dollars. The state allocated some American Rescue Plan dollars to child care providers directly, which in turn helped pay for personnel and other costs. That money won’t exist forever.

Child care advocates are focused on expanding pre-K access, but they also acknowledge that many of the shortages are often more severe for infant and toddler care. Each child needs a crib, and the required teacher-to-child ratio is larger for young children.

Early Learning Indiana has hundreds of families on its waitlist for young children. In some cases families age out of infant care before even making it off the waitlist.

“It is a crisis in many communities for infant and toddler care,” Weber said. “If [early child care providers] can’t figure out our challenge, the rest of the state will have a very hard time coming up with the workforce that it needs to carry out whatever its activities are.”

The rest of the child care puzzle

Indiana lawmakers have invested in child care in the past year, aside from just expanding the pre-K eligibility requirements. In the second year of the two-year state budget, they added $5 million to On My Way Pre-K. Snideman called it the “most impactful session” on pre-K since the program was created.

“It certainly doesn’t serve all of the unmet needs that our partners at Early Learning Indiana have identified,” Snideman said, “but it does go a long way toward making sure that more kids in our state have access to a good quality educational experience.”

According to the FSSA, 11,000 more Hoosiers children will now be able to access child care assistance, either through On My Way Pre-K or through the federal Child Care and Development Fund, which uses the same eligibility requirements as On My Way Pre-K.

Plus, Holcomb requested $25 million in the state budget this year to provide incentives to employers to expand child care for their employees. And, the state will be doling out $10 million worth of one-time federal and state dollars to those providers seeking to expand their high-quality early education offerings.

“We have further room for growth when you compare us to other states,” Weber said, “but we’re heading in the right direction.”

How to apply for On My Way Pre-K

To apply for On My Way Pre-K, go to https://earlyedconnect.fssa.in.gov/onlineApp/home.

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …