Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoAutistic children of parents on Medicaid may miss out on a needed therapy, lawmakers warn

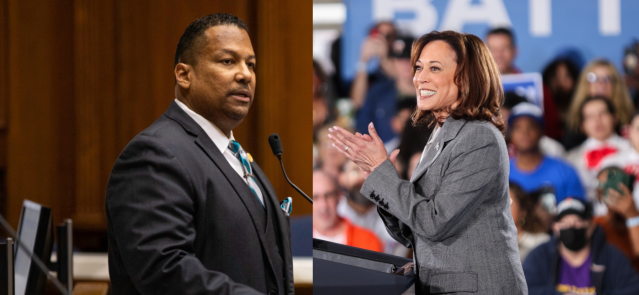

Rep. Robb Greene, R-Shelbyville, is pictured with his son, R.G., at the Indiana Statehouse. (Credit: Robb Greene)

R.G. Greene was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at 3 years old. He struggled to speak. But with help, he learned to talk when he was 5. It was then that R.G. told his father he loved him for the first time.

Rep. Robb Greene, R-Shelbyville, credits his son’s improvement to applied behavior analysis, or ABA, therapy. The therapy helps people — often children with autism spectrum disorder — become independent by learning to control their behaviors.

Last month, the state, through the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration, set new Medicaid reimbursement rates for the services, which go into effect Jan. 1.

But Greene, other lawmakers and service providers still warn the rates are too low and could cause clinics offering the services to close or force them to prioritize care for families on private insurance to stay in business.

The fallout, they say, could leave Hoosier families receiving Medicaid coverage unable to find the same care that altered R.G.’s life.

The need to curtail Medicaid costs

Since 2016, ABA therapy providers have been reimbursed through Medicaid by an office within FSSA for 40% of service costs. But providers have charged disparate fees, resulting in some providers being reimbursed more for the same services.

And as demand for the services has grown, so have the costs.

Federal data shows 1 in 36 U.S. children are now diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. In 2022, Indiana Medicaid programs provided ABA therapy services to about 6,200 children and young adults each month, according to the agency. The demand resulted in $420 million in annual claim payments to providers in 2022.

“Over the last three years ABA expenditures have increased by more than 50% per year, which is not a sustainable rate,” the agency posted on its website in August.

That standardized rates need to be set is not being questioned. “It doesn’t take a policy wonk in Medicaid to understand that reimbursing 40% of whatever is billed isn’t sustainable,” Green said.

To curtail the ballooning costs, the agency drafted preliminary reimbursement rates for all ABA therapy services in August, at the behest of the General Assembly.

One rate, in particular, drew criticism: a $55.16 hourly rate for registered behavioral technicians. The technicians’ services account for the majority of ABA therapy Medicaid expenditures billed to the agency. In the first quarter of this year, the average reimbursement rate for the service was $97 an hour and ranged from $21 an hour to $800 an hour depending on location, according to the agency.

On Aug. 18, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch wrote a letter to the agency expressing her “significant concerns” with the proposed reimbursement rates, arguing they were too low for providers to continue operating the way they are. In late August, Green authored a letter, signed by a bipartisan group of 13 state senators and 29 representatives, urging Gov. Eric Holcomb to intervene in the matter.

The final rates

Following the pointed criticism, the agency revised its rates, increasing the technicians’ rate to $68.24 an hour. The revised rate was similar to providers’ average operating cost, as determined by a study from two years ago — $68.12 an hour.

Crouch told State Affairs at the time that the new rate was “better than it was.” But many critics said it should still be higher. Green told the (Franklin) Daily Journal the hourly rate should be “in the mid-$70 range,” a sentiment echoed by other lawmakers.

However, despite continued worries, lawmakers on the State Budget Committee unanimously approved the rates in late October.

“It didn’t end the way we would have liked to see it,” Rep. Becky Cash, R-Zionsville, said.

A Family and Social Services Administration spokesperson didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. The agency has argued the technicians’ rate is higher than what is reimbursed in neighboring Kentucky, Ohio, Illinois and Michigan. The rates will be revisited again in four years, as part of the agency’s long-term plan to review all Medicaid reimbursement rates. The agency also plans to increase rates 2% each year to account for inflation.

Concerns remain

With the new rates set to take effect Jan. 1, some lawmakers and providers still predict small clinics that offer individualized care, especially in rural communities, might close as soon as summer.

“If other clinics go out of business or don’t expand or even contract the number of clients they serve, obviously, those families will be out of service,” said Miles Hodge, co-owner of Shine Pediatric Therapy in Indianapolis, an ABA therapy service provider. “Either those families will have to find a new clinic, or they will have to go without services.”

Hodge foresees waitlists for clinics “getting longer and longer,” and children “going without services for months or a year-plus before they are able to get in.” New clinics might be dissuaded from opening because “there’s a lot of startup costs,” and Medicaid historically reimbursed them at higher rates than private insurers, he said.

“They really tried to push it through really quickly before they were able to hear from the people who would be impacted by this,” Hodge said of the agency’s process for establishing the rates.

Kim Dodson, CEO of The Arc of Indiana, a nonprofit that helps people with developmental disabilities, believes some children with autism spectrum disorder in rural communities might go without care if the small clinics close. “As I talk to providers, I think $68 will be difficult,” she said. “We need more providers serving our rural areas and our minority populations, so, for me, that is a huge concern.”

But Dodson is unfazed by some providers leaving the state,especially those who have taken advantage of the state’s 40% reimbursement model. “They can leave,” she said.

What to look for moving forward

Critics of the rates expect to have a better understanding of how the reimbursement rates will affect clinics by summer, when interim committees begin meeting. Their hope is that “you’ll have six, seven, eight, months of information, data,” Greene said.

Greene wants legislators to “make sure that we’re not losing access, we’re not damaging providers, we’re not slipping in terms of our reputation in the state of Indiana for being a place where families with children on the spectrum are supported.”

Greene and Dodson proposed the topic be studied by an interim study committee next year.

“I know what ABA did for my child, and the concern that I have is this is an intervention,” Greene said. “You need to catch your child as quickly as possible when you get that diagnosis, to get them into that intervention and get them the resources to … have a degree of independence.”

Contact Jarred Meeks on X @jarredsmeeks or email him at [email protected].

X @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairspro

Header image: Rep. Robb Greene, R-Shelbyville, is pictured with his son, R.G., at the Indiana Statehouse. (Credit: Robb Greene)

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …