Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoThousands of Hoosiers will soon lose Medicaid access, but the cost of the program is still increasing

(Design: Brittney Phan for State Affairs)

- A net 400,000 Hoosiers are expected to lose Medicaid access over the next year due to the end of a pandemic-era policy.

- In the first month of the policy change, a majority of those who lost access to Medicaid did so for procedural reasons, not because they were found ineligible. That signals a problem.

- Despite the expected decline in enrollees, Indiana’s Medicaid general fund budget increased by almost 40% in the two-year budget.

Hundreds of thousands of Hoosiers are poised to lose Medicaid insurance access over the next year due to the end of a COVID-19 pandemic-era federal policy that prevented states from kicking people off Medicaid.

Despite that, state costs for the health program serving more than 2.2 million low-income Hoosiers, including more than 60% of Indiana’s children, are only expected to continue to grow over the next two years. That puts pressure on the system and the state’s budget.

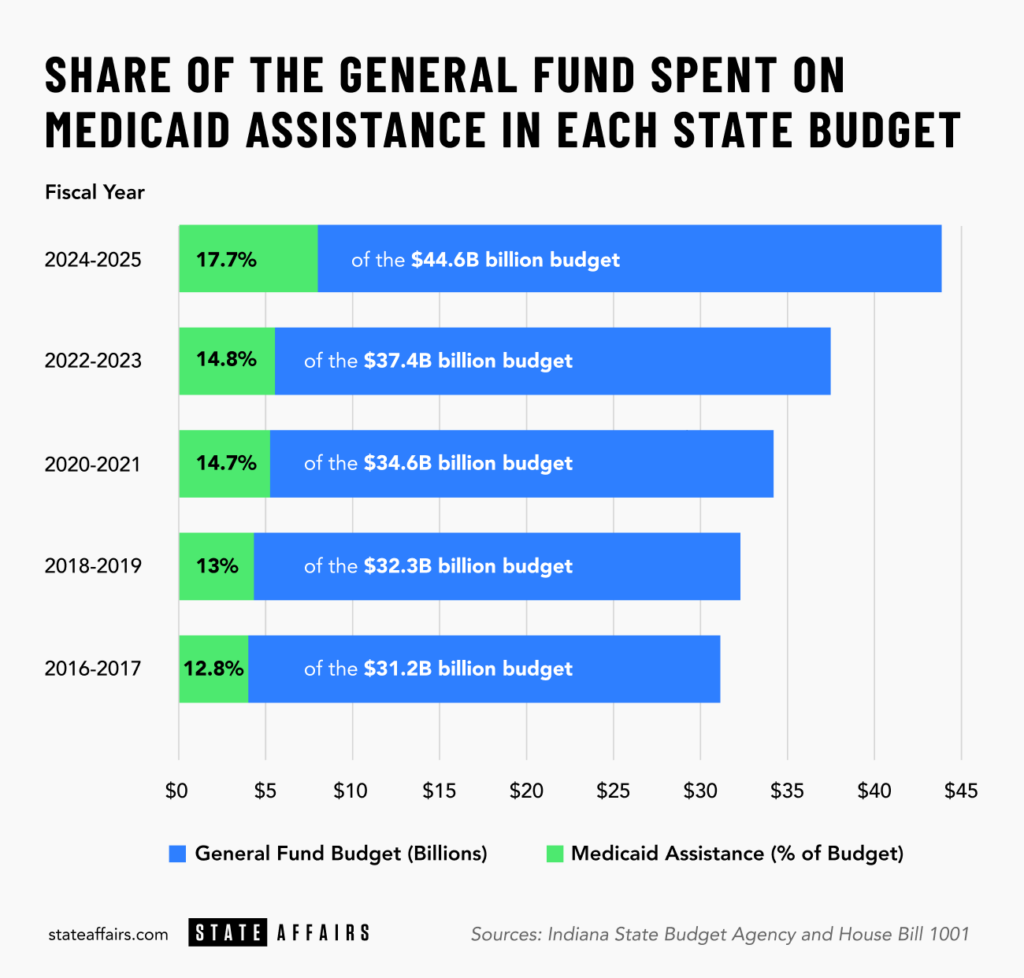

Indiana spends billions of dollars on Medicaid each year, making it the second largest expense to the state’s general fund following K-12 education.

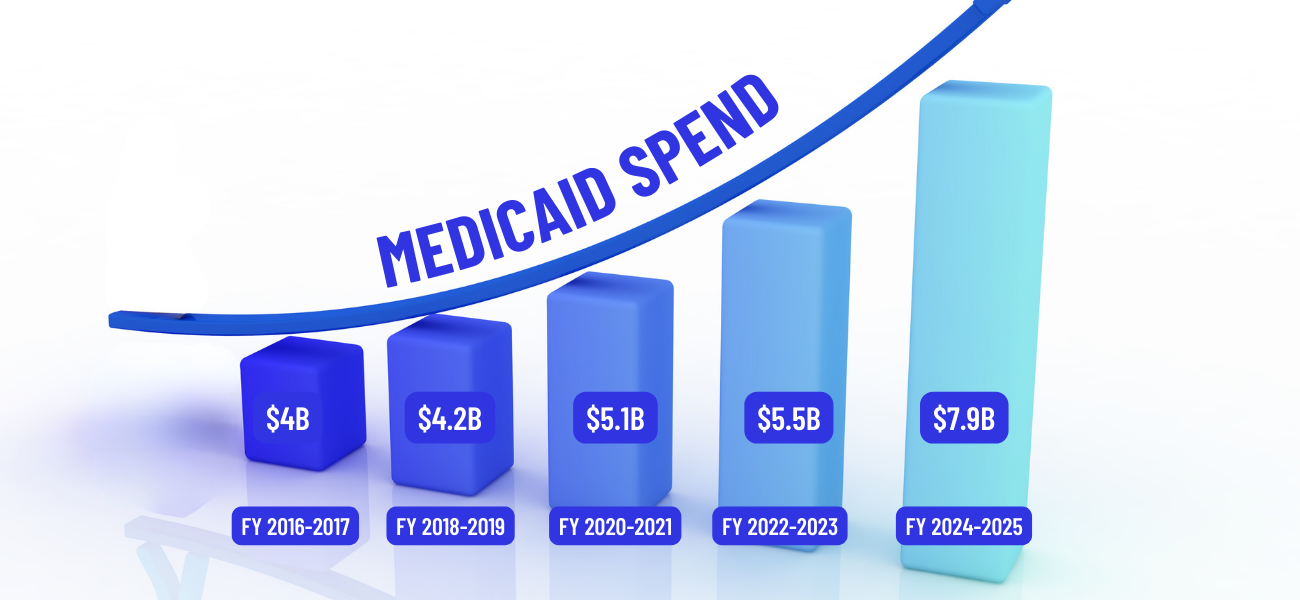

In the last decade, Medicaid assistance has doubled, growing at a faster pace than the state’s general fund budget as a whole. It now makes up nearly 18% of the general fund budget, which means less money for other priorities such as education, paying down state debt or infrastructure.

“If you ask me what I lay awake at night thinking about,” Senate President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, said at the end of the legislative session, “it’s Medicaid spending.”

The increased pot of money needed for Medicaid makes it challenging for advocates of either expanded access or increased Medicaid reimbursement rates to make their case. It also means some Hoosiers, such as those who rely on Medicaid for autism services, fear cuts may be coming.

Why so many Hoosiers will likely lose access to Medicaid

Over the next year, the state estimates that a net 400,000 Hoosiers, or nearly one-fifth of the number currently on Medicaid, will lose their Medicaid insurance access.

During the pandemic, the federal government prevented states from disenrolling people from Medicaid even if they were no longer eligible, in exchange for more federal dollars. That caused the number of people on Medicaid in Indiana to increase by more than 800,000 enrollees over the three-year period.

The Biden administration prohibition ended at the end of March, which means that for the next year, the state of Indiana will start double-checking whether those receiving Medicaid still qualify, in a process known as unwinding.

Advocates are worried some people will be kicked off by accident, or won’t realize they lost insurance until it’s too late and they’re hit with a doctor’s bill. The Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA) is sending people at risk of losing access a notice, but Adam Mueller, executive director of the Indiana Justice Project, and other advocates say it’s possible people either won’t get the notice or won’t understand its importance.

“Our biggest concern is that folks who should still be eligible for Medicaid or HIP [Healthy Indiana Plan] or any of the programs could lose coverage for procedural or administrative reasons,” Mueller said. “Even where there’s not a giant unwinding going on, people slip through the cracks.”

To that point, a recent report from the state found that of the roughly 52,000 people who lost coverage in the first month, more than 88% of them lost their Medicaid simply due to procedural reasons such as failing to respond to FSSA, not because the state found them ineligible. That could signal a problem in how Indiana is unwinding, said Joan Alker, executive director and co-founder of the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University.

“When you see a lot of procedural losses, there’s probably a lot of people, particularly children, who remain eligible, but they’re getting terminated anyways,” Alker said. “Is the state making clear that the children and the parents may have different outcomes, that like the parent is losing [Medicaid access, but] the child is still eligible?”

Advocates also fear that those who do lose access because they are no longer eligible won’t know where to find low-cost insurance options and will go uninsured instead.

So why are the costs still ballooning?

With a net decrease in Medicaid enrollees on its way, it seems counterintuitive that the costs for the program to the state would increase, so why is Indiana’s Medicaid general fund spending poised to increase by almost 40% from the previous budget?

It’s partially because the process of double-checking Medicaid eligibility will take 12 months, which means Indiana will continue to feel the effects of the pandemic requirement until May of next year. Meanwhile, the extra funding from the federal government, which typically covered the extra costs of continuous enrollment to the states, will be phased out by the end of 2023.

“There’s been some inaccurate rhetoric and claims flying around that states have been forced to carry this population, that it’s been very burdensome on them,” Alker said. “That wasn’t true because the federal government was giving them extra money.”

But even if the pandemic requirement had not been a factor, Indiana’s Medicaid costs would likely have increased due to the growth in those enrolling, and are poised to continue increasing in the future. Michele Holtkamp, a spokeswoman for FSSA, said that’s being driven largely by an increase in the number of seniors in Indiana, who often require more costly care.

Hoosiers aged 65 years and older are making up a growing share of the population, and that trend isn’t expected to slow down in the coming years. By 2030, 1 in 5 Hoosiers will be senior citizens, according to a 2018 report from the Indiana Business Research Center.

“That’s just something we and every other state in the country will have to deal with,” Allison Taylor, interim Medicaid director for FSSA, said during an April Medicaid forecast presentation.

Likewise, the state is spending more on behavioral health costs for children. There’s currently no uniform reimbursement rate for Applied Behavior Analysis therapy, commonly used to help children with autism, which means reimbursement amounts are often significantly higher than in other states, Holtkamp said. In 2022, the state spent $420 million on such services, which she called “not sustainable.”

Indiana has also expanded Medicaid in other ways. For example, a new federal rule will require states to provide 12 months of continuous coverage for children enrolled in Medicaid. That protects children from going off and on Medicaid due to minor changes in their parents’ income or other “red tape losses,” but once again, there is a cost. Indiana also extended postpartum eligibility.

The most recent data available from Kaiser Family Foundation puts Indiana near the middle of the pack when it comes to per-enrollee spending for Medicaid and 39th when comparing how much of the general fund is made up of Medicaid spending. But without more recent data, it’s challenging to know how Indiana compares today to other states.

What’s the solution?

Finding a way to stop costs from increasing is complicated because, typically, activists and lawmakers are pushing for an increase in Medicaid access or reimbursement rates — both of which might help Hoosiers but could drive up costs more. Already, Indiana requires those making over a certain income level to make a monthly contribution to their health care.

Some lawmakers pointed to one solution: fix Hoosiers’ dismal health outcomes in hopes that it will reduce the need for care among those using Medicaid. Valparaiso Republican Sen. Ed Charbonneau, who championed a revamp of the public health system in Senate Bill 4, hopes his bill will help.

“This may be a way to bend the curve just a little bit, because unless we prevent people from getting sick … it’s going to get worse,” Charbonneau said. “We can’t keep it up.”

Beyond that, Indiana could strengthen eligibility requirements or lower Medicaid reimbursement rates, both of which would likely be unpopular.

Starting this year, FSSA is undergoing regular Medicaid reimbursement rate reviews. That means costs to the state could go up or down depending on what rates the agency lands on.

Could those reviews cause problems?

They could. This year, for example, lawmakers are coming up with a uniform reimbursement rate for Applied Behavior Analysis therapy. That means some providers could experience cuts.

Indiana ACT for Families, which aims to protect access to care for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, actively pleaded with lawmakers and the Holcomb administration during the legislative session not to cut funding.

“The outcome of this review has existential repercussions for the children we serve,” the organization wrote in an April letter to lawmakers. “A sudden and steep funding cut would make it extremely difficult for some providers to continue operations and would reduce availability of quality ABA therapy that is critical to the children and families that we serve.

Meanwhile, other Medicaid recipients spent the legislative session pleading with lawmakers to increase reimbursement rates. The Indiana Hospital Association, for example, said Indiana’s current rate only covers about 53% of costs.

What’s next

Indiana is poised to share the first batch of proposed Medicaid reimbursement rates within the next few weeks, Holtkamp said. The state will look at others, such as hospital reimbursement rates, during the next budget cycle.

Aside from that, Mishawaka Republican Sen. Ryan Mishler, the chief budget architect on the Senate side, has made it clear that he wants to be very picky when it comes to legislation that would increase Medicaid costs.

“We still have a lot of bills out there where members want to keep expanding it and adding more people to the program, and that’s something we have to take a look at is how much do we really want to keep expanding? Because once we do it’s ongoing,” Mishler said during the legislative session. “We just have to figure out the growth of the Medicaid.”

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …