Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo‘Completely dysfunctional’: How public health funding disparities are causing dangerous inequities in care

When an HIV outbreak threatened a rural community in Scott County in late 2014, the county near the Kentucky border was thrust into a political and moral debate over whether syringe exchanges were an appropriate way to handle a dangerous outbreak caused by intravenous drug use.

But, the outbreak also uncovered what should have been a less controversial problem in the county: A lack of HIV testing.

At the time, Scott County’s health department, operating on a shoe-string budget with only five full time employees, did not offer such testing, and the local Planned Parenthood in the area that previously did so closed in 2013.

Had there been earlier testing — and an earlier response — to the HIV outbreak in Scott County, a 2018 study from two Yale University professors found, there could have been just 10 infections.

Or fewer.

Instead, hundreds of infections were attributed to the outbreak that rocked the Austin, Indiana, community of just 4,000, the largest HIV outbreak seen in Indiana history.

“It was just kind of a perfect storm of a lot of things. There wasn’t any free prevention testing going on,” said Michelle Matern, the Scott County Health Department administrator. “And then there was a lack of health education.”

The outbreak in Austin, as well as the more recent COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrates the necessity of public health departments and the services they could be providing if properly funded.

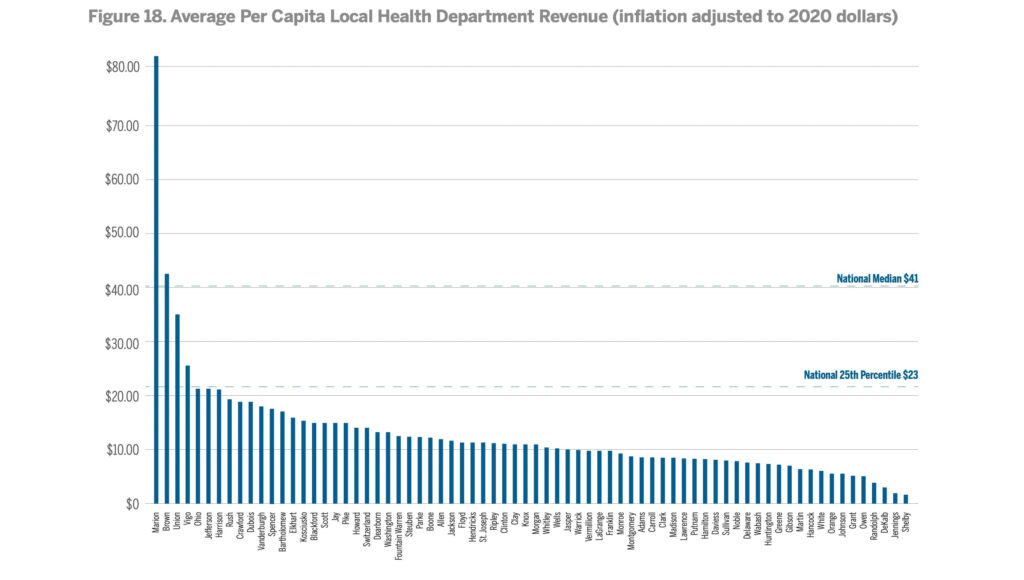

Before the pandemic, Indiana only spent $55 per capita on public funding, compared to the U.S. average of $91, according to a report from the Governor’s Public Health . In fact, of the health departments that provided data, all but four reported revenues beneath the national 25th percentile in local health department funding.

That matters in a state falling behind on nearly all health metrics, from obesity to early adult mortality. Perhaps the most important metric of all: Indiana ranked 40th in life expectancy in 2018, nearly two years below the U.S. rate. And the gap between the Hoosier state and the U.S. on that measure is only getting worse.

The Governor’s Public Health Commission issued a report this summer making 32 recommendations to fix the public health funding problem, including a whopping $243 million increase in state funding per year to help rightsize public health departments.

That would be just enough to put Indiana at the average per capita funding for public health departments in the U.S. But getting state lawmakers — most of whom have no health expertise themselves — to commit to that level of funding when they return to the Statehouse in January is a tall order.

If you ask Indiana State Health Commissioner Dr. Kristina Box, it’s time for that investment in order to ensure care is equal across Indiana.

“Philosophically, I think it’s important that every Hoosier has access to having their best potential health,” she told State Affairs. “I’ve been an obstetrician and done deliveries for 30-plus years now, and I’ve never delivered a baby for a family that didn’t want the absolute best for that child.”

But health departments need to be able to play their part to ensure that’s possible, she said.

Disparities between counties

The stark reality of Indiana’s public health system is this: Where someone lives dictates the level of public health resources they have access to in a state with already inequitable health outcomes, in part because of how little funding the state itself contributes to the system.

“It shouldn’t matter where you live in the state of Indiana,” said Paul Halverson, dean of the Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health. “Every resident of Indiana should be entitled to high quality public health services, because the reality is it’s not about the individual care, it’s about the care of the population.”

While the Marion County Health Department received $82.71 per resident in revenue, Shelby County received only $1.25 per resident in 2018, according to a 2020 Indiana Public Health System review from the Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health.

The public, though, is often unaware of the wide-range of initiatives health departments touch, from food inspections to septic system reviews to disease and trauma prevention, which means the problem has gone unnoticed.

So what does the financial disparity mean in practice?

In a state that ranks 42 for smoking and tobacco use, only 15 county health departments, including the well-funded Marion County department, reported offering tobacco counseling services in 2021. More than 11,000 adult Hoosiers die each year due to smoking, according to the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

Similarly, a child who lives in Vigo County, one of the top-four funded health departments in the state per the Fairbanks report, can get a physical at the child wellness clinic. In 2021, only four other counties reported providing any child well clinic services.

And in Vanderburgh County, which also has a better-funded department than most, the county engages with pregnant Hoosiers to provide wrap-around services for the first three years of their babies’ lives. Only eight other counties reported providing prenatal care services, despite Indiana’s status as the 9th worst state for infant mortality in 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Meanwhile, in 2021, at least 13 counties reported not providing blood lead screenings, despite the known health problems associated with lead exposure.

In fact, for years, the state health department didn’t follow Centers for Disease Control standards regarding when to investigate elevated blood levels in children. The reason: A lack of local health department funding and an unwillingness from state health leaders to implement another unfunded mandate that some local officials would just have to ignore.

The required basics aren’t necessarily being met in every county already. Box, the state health commissioner, said a local health department official told her they were responsible for emergency preparedness, food safety and septic systems. But because that employee was busy and didn’t really understand the food safety portion of the position, the county just wasn’t providing routine restaurant inspections.

Even in the larger Allen County Health Department, department administrator Mindy Waldron said it’s near impossible to focus on preventative measures, such as addressing the state’s dismal infant and maternal mortality rates or helping schools vaccinate children, when the county is already struggling to do the bare minimum required of it.

The department also has no trained epidemiologist, despite its status as the third largest health department in the state.

“We rob Peter to pay Paul every day to get to wherever we need to do these services,” Waldron said.

The lack of funding also means employees are spread thin. Waldron oversees the 66-person department, writes grants, works as a community health educator, completes half of the emergency preparedness planning and handles any human resources issues that may come up. She has no assistant, so when she has the day off, she’s often still working.

“We’re on all the time, because there’s no other us,” Waldron said. “When people do leave employment, it’s usually because they are overworked.”

The root of the funding problem

A primary reason local Indiana health departments are poorly and inequitably funded is because on average more than 70% of their funding comes from county governments, whereas on average nationally, most local health departments only receive about 25% of their funding from local governments. Other funding comes from federal direct or pass-through payments, state dollars and services and fees.

St. Joseph County health officer Robert Einterz called the current system, with its lack of centralization, “completely dysfunctional.”

That means health departments are funded based on what local elected officials deem is most important, most of whom don’t have health expertise and some of whom are distrustful of some public health initiatives following the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Those counties have to use that [money] to address their court system, their jails, their roads and other things,” Box said. “There’s just oftentimes not really much money left to be able to invest in local public health.”

Sometimes elected leaders are also either reluctant to apply for federal grants, because they either don’t want the federal government involved in local government or because they don’t want to be stuck with the bill after the grant ends, health officials say.

In other cases, there is a classic chicken and the egg conflict. Because local health departments don’t have the resources to hire someone dedicated to evaluating federal grants, they don’t apply for certain time-consuming grants in order to get more resources.

Similarly the health department in Hendricks County missed out on a grant for an infant mortality review team because they didn’t have physical space for another employee, said Michael Aviah, a public health education specialist in the county.

Counties such as Hendricks have succeeded in part because it’s created partnerships with local nonprofits or hospitals, which enables it to complete health assessments and act on those results. But coordinating those partnerships takes resources, too. Hendricks County has a position dedicated to partnerships.

When a local health department has one person handling all environmental complaints, there just isn’t the staffing to dedicate to forging those relationships.

“There’s definitely a lot of energy and time and resources that goes into building and establishing those relationships,” Aviah said. “I could definitely see that being a barrier if you don’t have the capacity to do that.”

Rural counties feel the pinch

The problems caused by a shortage of funding is exacerbated in rural communities where county officials are forced to choose what to do with a smaller pool of money.

Owen County’s health department, for example, was among the lowest-funded health departments in the state per capita pre-pandemic. The rural county, which sits between Bloomington and Terre Haute, currently only has three full time positions and one part-time position in its health department, in addition to four contract employees funded by temporary grants that will all eventually end.

There’s plenty of services Christina McBride, the county’s health administrator and vital registrar, would like to provide if the department was provided more money, such as offering transportation to doctor appointments, providing physicals or even simply investigating and cleaning up more unsanitary, rodent-attracting trash complaint sites. The majority of doctors in the county are located in just one town within a two-mile area, and there’s no public transportation.

But the county of roughly only 21,000 people has a limited budget, about 1/17th the size of Marion County’s.

“This county is poor,” McBride said. “They’re in a financial bind all the time, so they’re not going to be willing to give us any extra.”

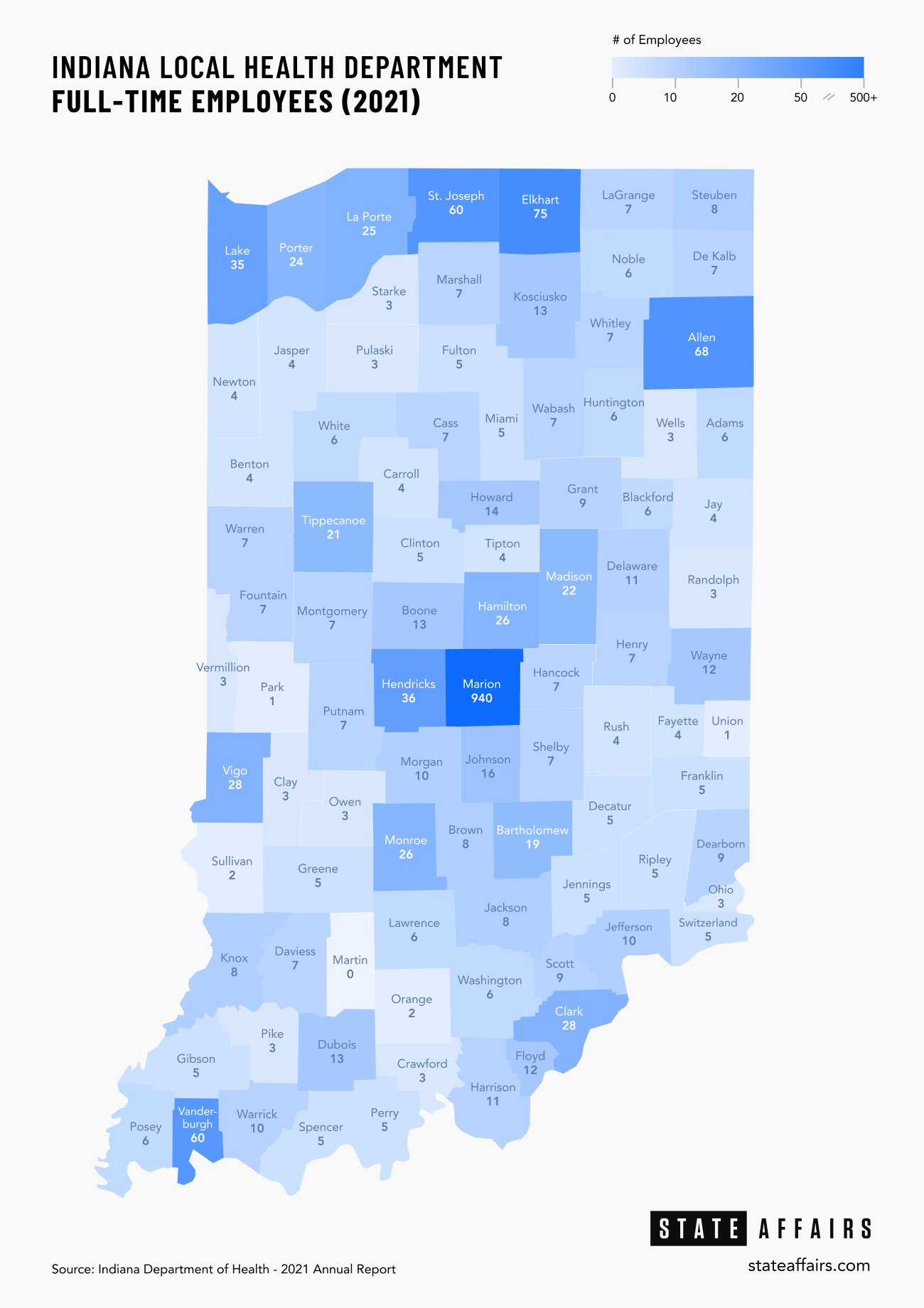

As of 2021, counties reported having a median of seven full-time health department employees, ranging anywhere from zero full time employees in 10,000-resident Martin County to 940 in Marion County. That means county employees are forced to take on multiple roles, sometimes without adequate training.

It also means that if an employee gets injured, sick or quits, communities are put in a bind and have to either rely on other cash-strapped health departments to lend a hand or temporarily stop providing the service.

In Ripley County, a rural community near Cincinnati with fewer than 30,000 people, the health department was forced to struggle with a staffing shortage after the person responsible for inspections of new construction quit, said Dr. David Welsh, the county’s health officer. That delayed permits on new construction for buildings and homes for weeks while the county looked for a backfill, despite some help from other communities and the state.

Welsh, and multiple other health officials, also expressed concerns about a lack of data available to counties, as well as the ability to analyze that data. Currently, schools in his community are dealing with high absentee rates. He’d like to know about disease upticks and be able to warn schools before it starts impacting school attendance.

“I’d like to get a heads up that the horse is trying to break out of the barn before it’s out of the barn and down the road,” Welsh said, “and that comes from acquiring data and analysis of data.”

Even in some larger counties, such as St. Joseph County, the lack of data is problematic. Einterz, the county’s health officer, emphasized that he’d like to be able to get a handle on why some people aren’t getting regular cancer screenings. That’s data he just doesn’t have.

The Solution

For the governor’s Public Health Commission, the solution begins with an infusion of cash to each county health department. The commission asked state lawmakers to set aside an additional $243 million each year in this upcoming budget cycle.

Even with the weight of Gov. Eric Holcomb himself behind the Health Commission as well as that of Luke Kenley, a former influential senator who co-chaired the commission, getting support from a majority of lawmakers, including those who lead the budget-writing process, will be challenging.

“Even though the pandemic has put the spotlight on healthcare, we never had, during the entire time I was in the legislature, any kind of comprehensive review of the public health program,” Kenley said. “It’s like a brand new subject almost, and anytime you get into a new subject, then you’ve got to go back to ground zero and explain a lot of basics and get people up to speed.”

Budget writers are grappling with countless other budget requests this cycle, such as more education or mental health funding. There’s only so much to go around in a Republican state legislature dedicated to maintaining significant reserves and lowering taxes, amid concerns about inflation eating up any extra revenue.

Senate President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray said last month that he couldn’t see the legislature spending the combined $480 million in the next two-year budget that’s being requested for public health.

“I think it might be difficult,” Bray said. “That’s a big bite.”

But health advocates point to other large dollar numbers: The extra costs associated with health problems in Indiana that could have been prevented.

Chronic diseases, for example, directly and indirectly cost $75.5 billion in Indiana each year, and smoking results in $3 billion in annual healthcare costs for Indiana, according to the Public Health Commission’s report.

Sen. Ed Charbonneau, chair of the Senate Health and Provider Services Committee, is hopeful he and other health advocates will be able to get the total requested funding in at least the second year of the budget.

The Valparaiso Republican is carrying the health commission’s bill this upcoming legislative session, which starts in January. In addition to providing extra funding for county health departments, his bill would create regional districts that would better allow the state health department to communicate and pass resources onto individual health departments.

He knows the funding specifically is a hard sell. Complicating the issue: Changing health outcomes won’t happen overnight even if funding is poured into the system.

“A big issue we’re going to have to deal with is education of the public and I think the legislators, about where we are, why this is important,” Charbonneau said. “One of the primary things for me going forward is changing the focus from treatment to prevention.”

It’s been about eight years since the HIV outbreak swept through Scott County. More than 200 people were infected, but health officials were eventually able to stem the tide, thanks largely to the help of a clinic offering syringe exchanges, information on recovery resources and, of course, HIV testing.

But in at least 60 other counties? HIV testing provided by local health departments remains out of reach, according to the health department’s 2021 report.

Some told State Affairs they don’t have the resources to offer it.

“There’s a dire need for it because a lot of people don’t know where they can get tested,” said Aviah, whose county no longer provides HIV testing. “It’s really important that we, the health departments, are able to provide that.”

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Header photo: (Credit: Centers for Disease Control)

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …