Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoHow a proposed amendment to Indiana’s constitution would cut the right to bail

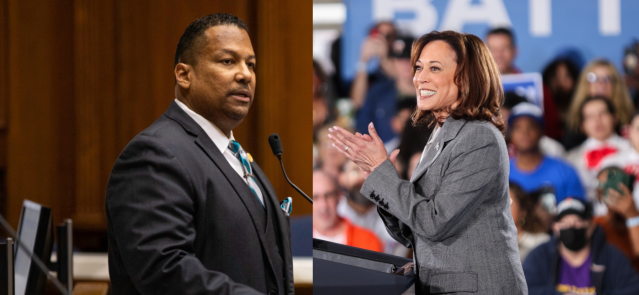

Senate Republicans are championing Senate Joint Resolution 1, which aims to amend Indiana's constitution to restrict the right to bail. (Credit: Brittney Phan)

- Hoosiers have a constitutional right to bail in most criminal cases

- But a proposed amendment would empower judges to keep more people in jail before trial

- The measure has wide support, but some are concerned about the erosion of rights and due process

The Gist

Fewer people would be eligible to bail out of jail in Indiana under a proposal advancing through the state Legislature.

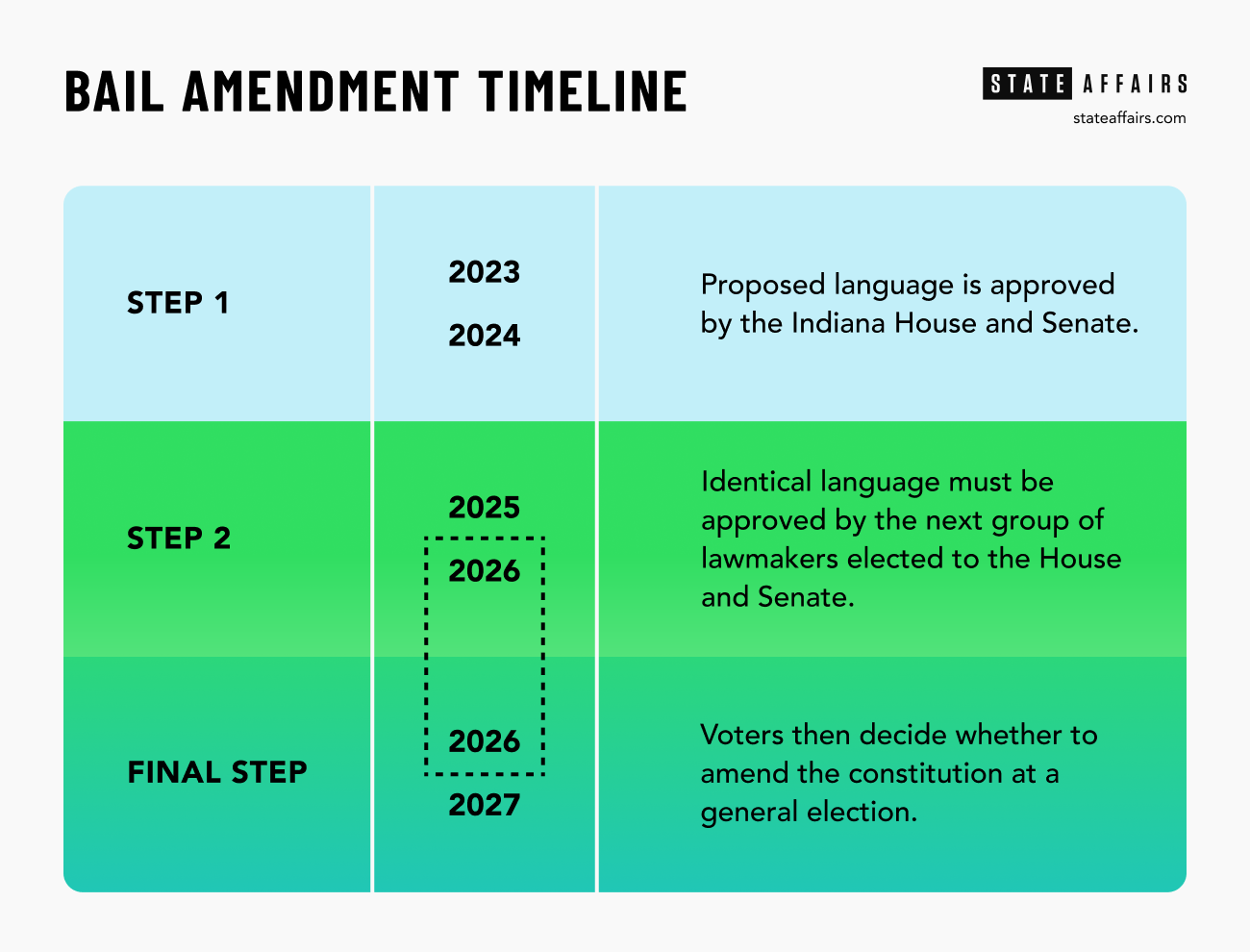

The change is not as simple as passing a new state law, however. It would require an amendment to the state constitution, which is a seldom-used, yearslong process that ultimately requires voter approval.

Widespread, bipartisan support is building among Indiana lawmakers, but opposition is also cutting across typical political ideology to bring together groups commonly seen as conservative and liberal.

What’s Happening

Indiana is one of 19 states where the state constitution guarantees the right to bail for almost everyone. If someone is accused of a crime and arrested, a judge typically must allow that person to post bail and leave jail while the criminal case is pending. (The constitution carves out exceptions for murder and treason.)

That would change under the language contained in Senate Joint Resolution 1.

Senate Republicans — who for years have expressed concerns about the growing number of murders and other violent crimes, particularly in Indianapolis — proposed the legislation.

SJR 1 would allow a judge to keep someone in jail if the person is deemed a “substantial risk to any other person or the community.” To do so, it would require prosecutors to meet a clear and convincing evidence standard, which is a relatively high bar to meet in court, just below what’s required to convict someone.

“The impetus was not a particular case, although it’s not unusual for a Hoosier to flip on their evening news or pick up their morning paper and see exactly the situation that this is trying to address,” Sen. Eric Koch, R-Bedford, told State Affairs. He is carrying the legislation.

But not everybody is on board with the proposed change to Indiana’s Constitution — including some conservative voices.

They are concerned about providing even more power to judges. They say the proposal is too vague, which invites judges across the state to interpret the same language differently.

Why It Matters

Supportive lawmakers, meanwhile, have noted that Indiana would join 22 other states that have constitutional language placing tighter restrictions on bail.

“We’re not reinventing the wheel here,” Koch told State Affairs. “I’m not aware of — and nobody’s brought to my attention — any of those states where there’s some kind of judicial chaos over very similar language.”

One key difference, though, is that 21 of those states also limit which types of cases are eligible for detention without bail, according to information maintained by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Ohio’s language, for example, specifically mentions felony charges; Indiana’s change, however, would allow preventative detention in all types of cases, even misdemeanors.

And seven of those 22 states contain another guardrail against judicial overreach in the form of more precise language about the risk posed by the defendant. Whereas Indiana’s proposed language is broad and open to interpretation, opponents say, those seven states’ constitutions possess specific language, such as if someone is a risk to physically harm someone else.

Sen. Sue Glick, R-LaGrange, raised similar concerns in a Senate speech back in January. The term “substantial risk,” in particular, was too vague for Glick. She revealed two ways the phrase could be interpreted by the courts.

“We’re afraid of someone and we would deny them the very liberty and freedom they’re assured because we’re physically afraid of them?” said Glick, who has worked as both a prosecutor and public defender in her career. “Or can it be that this risk — this fear, this danger — is the danger of ideas? Because many people throughout history have been imprisoned, deprived of their liberty and even their lives because of the danger of their ideas.”

Many of her concerns are shared by the Vera Institute of Justice, which is a nonprofit that advocates for alternatives to incarceration, and the Indiana Public Defenders Council (IPDC).

They also have sounded alarms about the potential impact on Indiana’s overcrowded jails, as well as concerns about due process. Indiana does not require the presence of a defendant’s attorney at initial hearings, when bail is set.

Put simply: A defendant’s freedom could be stripped by a judge before the appearance of an attorney. (Afterward, defendants can request a review of their bond with their attorney present, but opponents of SJR 1 believe that’s too late.)

Still, that decision can be appealed — it just might take several months. In the meantime, the defendant would remain in jail whether or not they’re guilty, maybe for as long as some jail sentences would otherwise last.

“The concern here is that we’re giving courts even wider latitude to hold people pretrial while the person is presumed to be innocent,” Bernice Corley, executive director of the IPDC, told State Affairs. “We’re going to have more people, I believe, detained. More people who will just plead for the sake of getting their freedom back.”

To illustrate her point, she cited data from the Marion County Jail, which she described at a crisis level of occupancy “almost constantly.”

Supporters aren’t concerned

Supporters of the proposed amendment believe many of the concerns are misinformed or overblown.

Courtney Curtis, assistant executive director of Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council, noted in a House committee meeting last month that the proposed amendment corresponds to language already contained within state statute. That, in effect, reduces the vagueness, Curtis said.

And other concerns about vagueness can be addressed by lawmakers during legislative sessions, but the first step is to amend the constitution.

She also emphasized ongoing efforts by the Indiana Supreme Court to urge local courts to proactively release people from jail who pose no risk. SJR 1, she said, would bring balance to that effort by requiring detention for people who are dangerous.

“This isn’t replacing the bail reform project,” Curtis told State Affairs. “It is continuing on with its initial goals.”

It’s also a more honest process, Curtis told the House committee. Right now, some judges attempt to work around the state’s constitutional right to bail by requiring defendants to post large sums of cash in order to be released from jail. Because a $500,000 or $1 million bond is out of reach for most defendants, it amounts to preventative detention anyway.

As a co-sponsor to the legislation, Rep. Chris Jeter, R-Fishers, said Hoosiers need a process that is not disingenuous. By amending the Indiana constitution, judges would be able to keep dangerous people while still releasing those who are not considered a risk.

“I think you’d rather just have the judge say, ‘I’m gonna hold you because you’re dangerous,’ and then issue the findings that come with why,” Jeter told State Affairs, “so the defendant knows why and has something he can attack or appeal if he doesn’t agree with it.”

The legislation is also supported by the Indiana Association of Chiefs of Police and the state Fraternal Order of Police.

And after receiving two amendments in the House, the bill gained votes from some Republican lawmakers who were previously opposed because of its initial broad language. It passed 70 to 19.

(Credit: Brittney Phan for State Affairs)

What’s Next

SJR 1 is headed back to the Senate for final approval in this year’s Legislature. It advanced easily before — 34 to 15 — and is expected to do so again.

But the process to amend the state constitution is lengthy. After approval in the Senate, Indiana must wait for the next General Assembly — so not next year, but in either of the next two years after that — to agree to the identical language proposed in SJR 1.

Then voters would have final say in a general election. The earliest would be 2026.

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: Senate Republicans are championing Senate Joint Resolution 1, which aims to amend Indiana’s constitution to restrict the right to bail. (Credit: Brittney Phan for State Affairs)

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …