Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoAndrea Hunley is a rookie Democrat from Indianapolis. Will she be heard in the Indiana Senate?

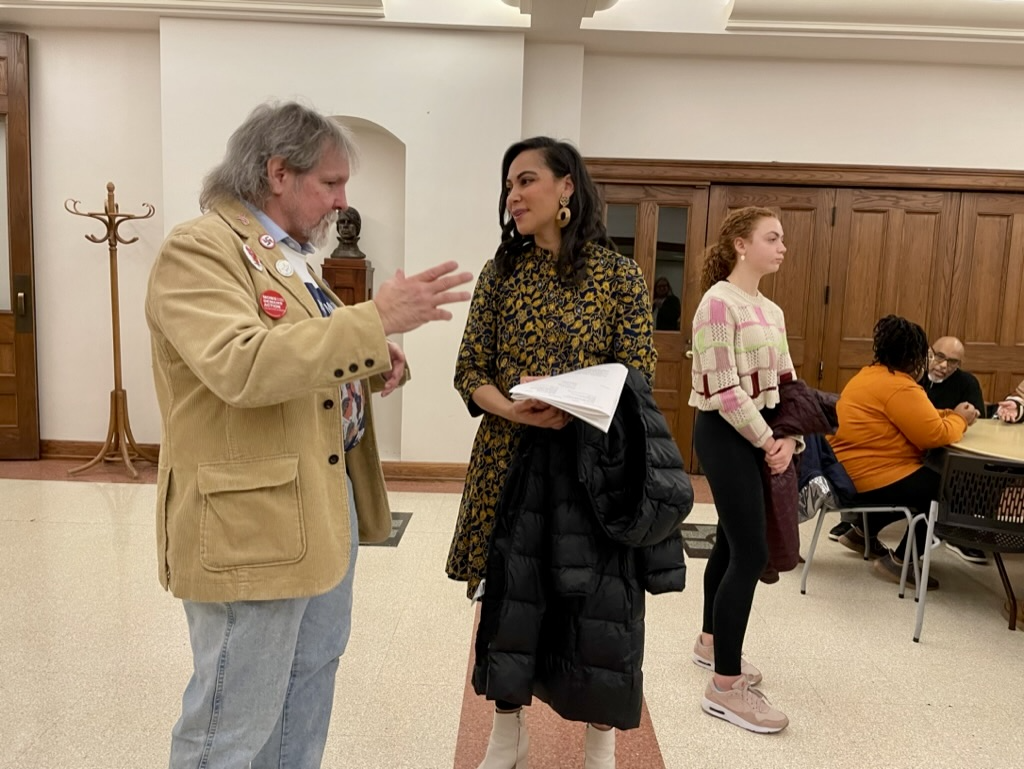

State Sen. Andrea Hunley, D-Indianapolis, stops for a portrait during a family outing Feb. 11, 2023 to the North Mass Boulder climbing gym in Indianapolis. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

Andrea Hunley and her teenage daughter stared at the rock climbing wall. Its red handholds snaked more than 10 feet into the air, but for two amateur climbers, the distance may as well have stretched five times that.

“I’m really bad at it, but it’s also really good to try something new,” Hunley, 38, told State Affairs. “I think it’s important for my kids to see me do things that are hard — and continue to push through.”

Her two daughters were also a big reason why Hunley, a longtime public school principal in Indianapolis, recently acquired another title: state senator. Hunley is the first person to represent a newly created district that spans the heart of the city.

And so, on that trip to the North Mass Boulder gym in February, Hunley reached for the first handhold. Then the next. And the next, until she soon found herself atop the wall, peering at her daughter below.

OK, Hunley said. You can do it, too.

* * *

Hunley isn’t thinking about metaphors on the trip to the climbing gym. For her, it’s a typical Saturday: She and her husband Ryan simply taking their 12- and 14-year-old daughters on an active family outing. When it’s not a hike through a state park or a historical walk down Indiana Avenue, it’s rock climbing.

But if Hunley ever let a fear of failing stop her, she might still be an English teacher living a relatively quiet life. She may not have enrolled in a master’s program while pregnant with her second child, later stepping out during breaks to meet her husband in the parking lot to nurse their newborn. She may not have become principal of the sought-after Center for Inquiry 2 in downtown Indianapolis, quickly earning the nickname “BP” from one teacher (it stands for Baby Principal) before garnering respect and admiration from educators and parents over 11 school years.

And she certainly would not have dared to join a competitive state senate race against four other candidates, including someone backed by the Marion County Democratic Party.

So far, any fear of failing has been washed away from an even greater feeling of responsibility, particularly in education policy.

“It frustrates me that people are legislating on things that I do not feel that they fully understand,” Hunley told State Affairs. “If you walk into a school and you ask a teacher what the biggest issues in education are right now, they would say teacher pay, our teacher shortage and literacy.”

* * *

It was in 2020 when Hunley began visualizing the steps that would one day take her to the Indiana Statehouse.

At the time, Hunley’s home lay in the district of State Sen. Jean Breaux, a stalwart Democrat who has represented Indianapolis in the state Senate for more than 15 years.

Hunley decided she would convince Breaux to become her mentor. And then when Breaux retired down the road, Hunley would be ready as her successor. Hunley began following Breaux’s work more closely. She attended her events, watched for bills that she filed.

“I started shadowing her,” Hunley said, “without her really realizing it.”

Breaux, informed this week by a State Affairs reporter of the secret shadowing, laughed and said she had no idea.

“I’m honored, actually,” said Breaux, who describes Hunley as someone who fights for her values and for what she wants — even if it means taking on the county Democratic Party.

“They told her no. And she said, ‘Senator Breaux, when they told me no, that’s when I decided I’m running.’ And I said, ‘You go for it then,’” Breaux said. “She’s tough. And she’s not a pushover.”

Hunley does not remember a time when she didn’t plan to eventually run for office. Her high school classmates in Fort Wayne even dubbed her as most likely to become the first woman elected as U.S. president.

She grew up learning from an engaged family. Back in 2003, her mom joined her aunt, who is a Catholic nun, in a drive to Washington, D.C., to protest the U.S. invasion of Iraq. She remembers the words on her mom’s sign: soccer moms for peace.

It was Barack Obama’s campaign for president, though, that drew Hunley into Democratic politics. Still in her early 20s, and working as a teacher at Ben Davis High School at the time, Hunley volunteered by staffing a phone bank at his Indianapolis office.

Curiosity led her to attend a Women4Change event in 2017 where former Indiana Lt. Gov. Sue Ellspermann, a Republican, spoke to a crowd of women inside an Indianapolis hotel ballroom. Women, Ellsperman said, typically need to be encouraged seven times before they finally decide to run for office, Hunley recalled.

“And so then she said, ‘I’m asking you to run. You need to run. You need to run.’ And she just said it seven times in a row,” Hunley said.

Micah Nelson, a friend and co-worker from school, attended the event with Hunley. She, too, had been considering running for office but that day clarified for her what should happen next.

“It was just clear through the conference that she should run for office and I would be happy to support her,” Nelson said. “We have a saying that strong women empower other women. I think that characterizes our relationship. We’re friends, we’re colleagues, we’re each other’s cheerleaders.”

Only one office interested Hunley, and that was state senator. She wanted a position that could shape education policy for Indiana. She’d maybe consider state representative but the two-year terms were too limiting.

So that’s why Hunley called her state senator, Breaux, in 2020. It was a step on her yearslong plan.

“And I know that my voice sounds like a 14-year-old,” Hunley said. “And she’s like, ‘Now who are you, honey? And how old are you? You want to do what?’”

But then came a shock in September 2021: Indiana Republicans, who were in charge of redrawing legislative districts following the 2020 census, changed the shape of state Senate boundaries in Indianapolis. Breaux’s district would now end northeast of Hunley’s home.

The new heavily Democratic district sat open for the taking.

* * *

Late one night, Hunley invited over two friends who know the tempo of the city’s politics. They agreed on one point: It would be hard for Hunley to win the Democratic primary.

The District 46 primary featured Kristin Jones, an Indianapolis city-county councilor backed by the Democratic Party who carried a fundraising advantage. The race also contained another strong candidate in Ashley Eason, who had experience running for another state Senate seat.

Hunley’s experience as an educator was undoubtedly valuable, said Laura Merrifield Wilson, a political science professor at the University of Indianapolis. That experience, however, is not always viewed in the same light as an elected position, she said. Hunley, after all, had never served in public office.

“But I think she either was just very bold or intuitive. She was willing to take that risk,” Wilson said. “She knew something that other people didn’t.”

Hunley confirmed to State Affairs what was rumored at the time: An awful lot of Democrats privately told her not to run.

“That’s what everyone told me,” Hunley said. “I mean, every single person told me that. Every single city councilor I talked to told me, ‘Don’t run. It’s not your turn.’ Even people who I’ve done a lot of work with and who I really trusted — even people who were in education and who I thought would be excited — they’re like, ‘Don’t do it.’”

Hunley ignored them. She announced her candidacy in November 2021.

One person who works within government affairs, though, cautioned that she lacked the financial support and it was going to be “really, really hard.”

So Hunley asked him: “Is this going to be white guy hard? Or is this going to be Black woman hard? Because I’ve only known hard.”

* * *

Hunley was still a baby in Indiana’s foster care system when her dad and mom found her.

“When she came to pick me up from the adoption agency, she says they handed her this naked baby with a dirty diaper on and she never put me down,” Hunley said. “And I feel like that is how my mom still raises me, like she has still not put me down, which I appreciate.”

Hunley grew up in Fort Wayne along with two siblings, both who were adopted, too.

Their parents were open about how their family came together. In Hunley’s childhood home hung a framed print from her parents: A prayer for my adopted child.

And her family celebrates her date of adoption — July 3, 1984 — as her special day, something more precious to Hunley than her birthday.

“I haven’t ever been a person who really gets excited about birthdays,” Hunley said, “because my parents weren’t there.”

Anyone who spends any time around Hunley can see how important her family is to her. Not only her kids and her husband Ryan — who she met while working on the high school newspaper — but her extended family.

Hunley’s parents, grandmother, sister and her sister’s four kids all live in Indianapolis now.

While taking classes in her master’s program, Hunley begged them to leave Fort Wayne to come help her. So they did, and they still gather for dinner at least once a week.

A few years ago, Hunley finally met her birth mother and half sister. She knew very little about them but was able to track them down.

“It was lovely to get to know them,” Hunley said.

Both visited Indianapolis for Hunley’s swearing-in to the state Senate. At the ceremony, someone asked Hunley who stood with her. She worried about introducing her birth mother because Hunley believed it was her birth mother’s story to tell whenever she was ready to tell it.

So Hunley responded with something broad: This is my family.

Then the other woman spoke up: “I’m her birth mother.” It was a weight off Hunley’s back.

She still worries, though: Will her adoption be used as a weapon against people who, like her, believe in abortion rights?

* * *

Because of her progressive politics, almost no one expected Hunley to make a splash in the Indiana General Assembly, especially not this year.

She has advocated for gun control as a volunteer for Moms Demand Action. She’s a strong supporter of the teachers union. She believes Indiana is underfunding numerous public services, including traditional schools and health departments. And teachers, at a minimum, should start at a $70,000 salary.

In a legislative body firmly gripped by Republicans, how is a rookie Democrat from Indianapolis supposed to accomplish much?

She refuses to let partisan disagreements serve as excuses for inaction. For one, she understands the power of what she represents. She’s one of five Black people serving in the 50-member Senate, and one of just nine women.

Hunley also admits to being something of an “eternal optimist,” but she believes she will make a difference by building relationships with every legislator and by being true to herself.

She’s already gained a fan in State Sen. Michael Crider, R-Greenfield, who chairs a Senate committee where Hunley serves as the ranking minority member.

Crider told State Affairs he’s been impressed by Hunley’s thoughtful approach to the legislation she’s invested in. One example is Senate Bill 233, which would create a task force seeking to improve pedestrian and vehicle safety. The bill moved through the Senate — an uncommon feat for a freshman, particularly one in the superminority.

“Really, serving as a legislator is people skills on steroids, where you’ve got to be a person of your word and you’ve got to say what you’re trying to accomplish,” Crider said. “And so I think her personality and the way she carries herself is going to help her along in building that credibility that needs to happen if you’re going to be successful long term.”

She began working toward that credibility on Organization Day, the November kickoff to the 2023 legislative session that truly began seven weeks later. For veteran lawmakers, it’s a homecoming; for freshmen legislators, it’s the calm before the four-month storm.

On that day, Hunley stood inside the state Senate chambers. She stopped Republican lawmakers to introduce herself, all direct eye contact and handshakes and smiles. She said hi to their kids and grandkids.

Then when she spotted Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, a Republican on the verge of announcing her run for governor, Hunley hopped to her and asked to take a selfie. Both smiled for the phone camera.

Earlier in the day, Crouch had leaned over to Hunley and said: ‘‘I am so glad we have another woman in the Statehouse.”

“Like, that’s really kind,” Hunley told State Affairs. “Here’s what I know: When women lead, regardless of party, when women lead, we really work hard to listen and to build coalitions and consensus and really make change. And so I have been really impressed by the work that she’s done. I’m looking forward to her run for governor.”

Crouch is facing Eric Doden and U.S. Sen. Mike Braun in the 2024 Republican primary for governor.

But Hunley’s interests in working across party lines may have a limit. Asked about the prospect of a Gov. Braun in 2024, Hunley’s words were less enthusiastic.

“Oh, heaven help us all,” she said. That’s because Braun made comments last March that suggested the legality of interracial marriage should be determined by states. (Braun later said he misunderstood the reporter’s question and walked back those comments.)

Hunley’s husband is white. Her parents are also in an interracial marriage.

“No. I do not have any nice words that don’t have four letters in them to say about that man,” Hunley said. “And so my mother has taught me to just keep my mouth shut when that’s the case.”

* * *

In a legislative session that kicked off with talk of avoiding so-called culture war issues, the last few weeks have seen plenty of divisiveness.

Some of the fiercest debate occurred on Senate Bill 480, which would ban some health care options for transgender youth, and on Senate Bill 12, which would open up teachers and librarians to criminal prosecution over what’s contained inside school books and other education materials.

Hunley spoke against both. She was perhaps at her sharpest when questioning another freshman lawmaker — State Sen. Tyler Johnson, R-Leo-Cedarville — about Senate Bill 480. She started by saying the two of them were on a shared journey as new senators, and she thanked him for representing some of her family members who live in the area of her hometown, Fort Wayne.

But then she dove in. She noted the bill sought to limit the intake of estrogen and progesterone, two hormones used in birth control pills. As a mom with daughters who might one day need the medicine, Hunley wanted to ask about the bill’s impact on her eventual discussions with doctors.

So Hunley stared at Johnson and asked: “Do you think if I’m sitting in that doctor’s office deciding which hormone is more suited for my child, that the state should make that decision, or that I should make that decision?”

Johnson did not answer her question, instead staring at his lectern while saying: “And I hear that you’re wanting to put kids through this process where they really have these irreversible, unproven, life-altering procedures done to them, and we’re the only body that has this moral, medical and legal authority and obligation to protect kids from this.”

It was language he repeated several times under questioning that day.

Hunley appeared to be confused by the response. She followed up: “So do you think having progesterone is life-altering? Like I’ve not been taking progesterone for many years, like is my life completely altered because I was taking it temporarily for a period of time?”

Johnson again did not provide a specific answer, instead saying: “I’m not going to comment on your specific case.”

The bill easily moved through the Republican-controlled chamber, but Hunley’s advocacy and questioning stood out to State Sen. Greg Taylor, D-Indianapolis, who heads his party’s caucus in the Senate.

“Senator Hunley has a way of professionally telling you you’re wrong, and I think it comes from being a teacher,” Taylor told State Affairs. “Being able to tell somebody, in a nice way, that you don’t know what you’re talking about. And she’s done that several times.”

* * *

Back in 2021, at the start of the campaign, Hunley’s daughter Addison dreaded talking to people.

Walking up to strangers’ doors to share her mom’s campaign literature? It was tough for the then 13-year-old.

“I could never just go in front of someone and ask a question,” Addison said.

Hunley, whose campaign centered on visiting as many voters’ homes as possible, continued to bring her. And something happened: As the weeks went by, Addison’s fears began fading.

“Continuing to knock on doors allowed me to, like, open up as a person,” Addison said. “It’s really helped me grow throughout my school experience.”

And back in February at the Indianapolis climbing gym, after watching her mom scale the wall, Addison reached for the handhold, and climbed.

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: State Sen. Andrea Hunley, D-Indianapolis, stops for a portrait during a family outing to the North Mass Boulder climbing gym in Indianapolis on Feb. 11, 2023. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that the protest of the U.S. invasion of Iraq was in 2003.

Know the most important news affecting Indiana

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

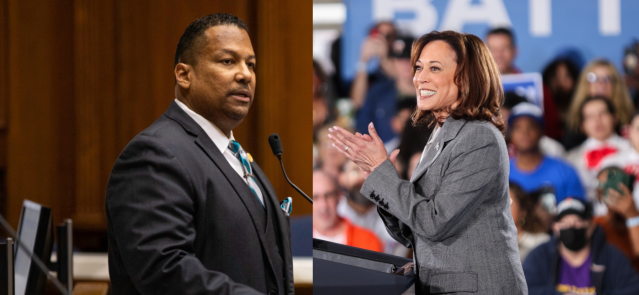

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …