Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoIndiana once had some of the cheapest electric bills. Not anymore.

Aaron Cooper, chief commercial officer, and Greg Ellis, plant manager, during a tour of AES Indiana's Harding Street plant in August. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Indiana relied on coal for almost all of its power for years, but now the state is in the middle of a complicated — and costly — transition to new sources of energy. In a new series of articles, State Affairs is examining the impacts of state policy and how Indiana’s energy transition is affecting residents. This is the first in that series.

The financial impact of Indiana’s energy transition can be found on Lucille Moore’s monthly electric bill.

Moore, 89, said she’s been meeting with other senior citizens in her Indianapolis neighborhood and at her church. They’re all dealing with the same problem: Ballooning electric bills are claiming more and more of their fixed incomes.

>> Is your electric bill going up? Here’s some ways to lower your costs

And AES Indiana, which services Moore and a half million other customers in the Indianapolis area, is now trying to take an even bigger bite starting next year.

That led Moore to attend a public hearing inside the city’s Central Library last month where she looked into the eyes of the members of the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission (IURC), the state agency that will decide if AES can raise prices. Moore urged them to say no.

“The increase is really hard on seniors,” Moore told them. “Please think of the seniors, because you’re going to be there, too.”

The proposed increases aren’t unique to Indianapolis. In northern Indiana, NIPSCO recently received state approval to raise prices for about 468,000 people. Indiana Michigan Power is seeking a rate increase, too, for the more than 600,000 customers in mostly northeastern Indiana. And CenterPoint Energy, which serves 140,000 people in southwest Indiana, is wanting customers to pay more as part of an infrastructure request.

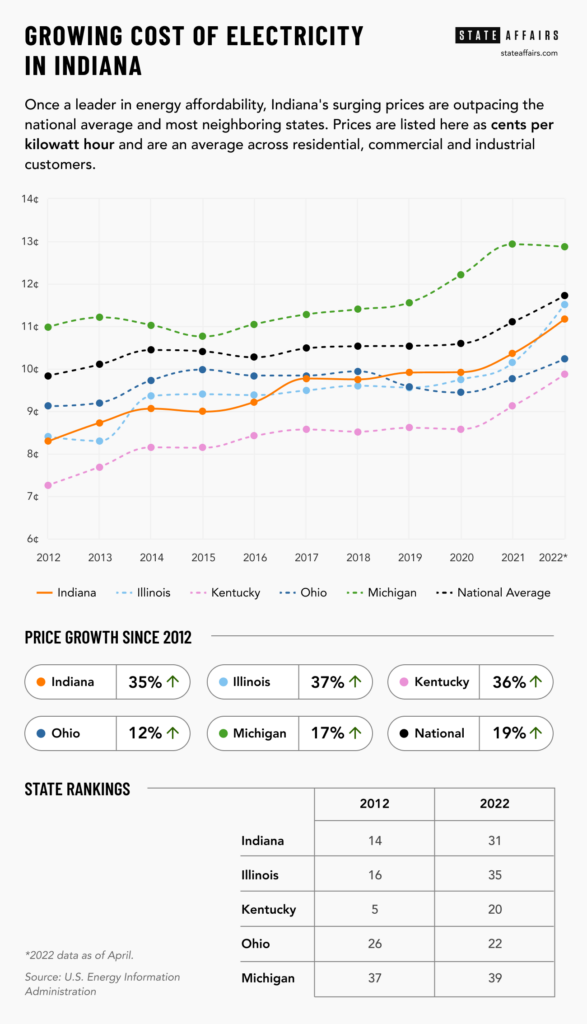

Their requests come as the average price of electricity in Indiana has already jumped nearly 35% between 2012 and 2022, according to a State Affairs analysis of federal and state data, while the national average grew by just 19%. Average residential bills in Indiana closely tracked the rise.

While Indiana once boasted having some of the most affordable electricity in the country, that’s no longer the case. Indiana was ranked 14th as recently as 2012; as of April last year, the state dropped to 31st — trailing nearby states Kentucky, Ohio and Tennessee.

And Hoosiers hoping to find relief anytime soon will be disappointed by what the most recent state forecasts show. The cost of electricity among Indiana’s five investor-owned electric utilities is expected to continue to rise through 2025 to the tune of 30%.

So why have Indiana’s electricity bills become so costly? And is there any hope that renewable energy sources will one day provide relief? Those are some of the questions that customers, lawmakers and utility observers are trying to answer during Indiana’s energy transition.

The story begins with coal.

Coal provided almost all of Indiana’s energy

Indiana burned coal for years. It was close by and it was cheap.

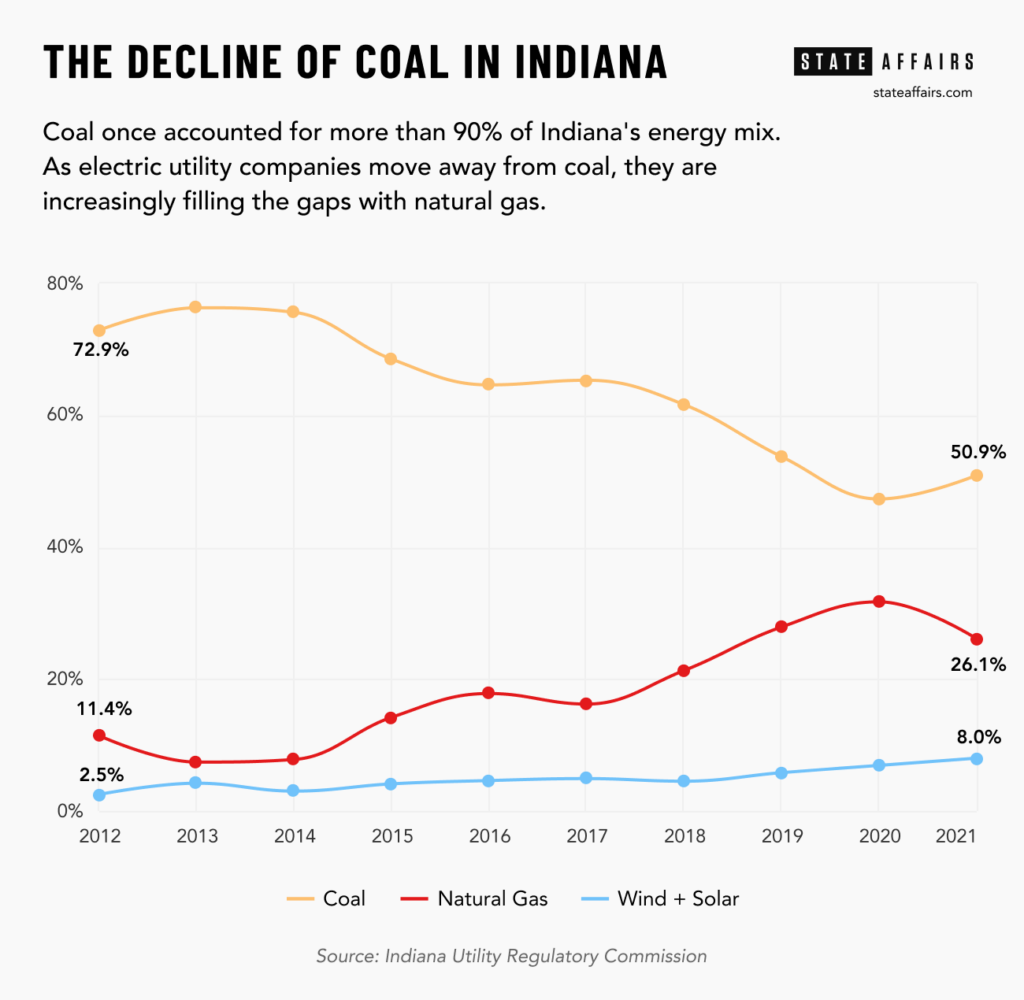

In the early 2000s, coal accounted for well more than 90% of the energy generated in Indiana. As a top 10 coal producer, the state benefited from the plentiful supply of a then-inexpensive resource.

But coal wasn’t actually inexpensive, as states would later learn. There are massive consequences to public health and the environment. As policymakers around the country began to comprehend that, they started shifting to new resources — especially as the federal government strengthened environmental regulations that created new costs to run coal plants.

Indiana, though, hung on. As recently as 2014, coal still accounted for about 75% of the state’s energy.

Why? It depends who you ask.

One reason may be because of how many jobs were tied to the coal industry. Even in 2021, coal production in Indiana was responsible for more than 5,000 jobs, according to a 2022 report from West Virginia University. Coal also served as a fertile political battleground — then-Gov. Mike Pence, for example, tried to fight the Obama administration’s plans to restrict carbon emissions in 2014.

Coal has now become some of the most expensive energy in the country. Yet Hoosiers — as a result of state policy in reaction to increased federal regulation — have already poured billions into coal-fired power plants. In some cases, they will pay for plants that are shelved while also paying for new sources of energy. It’s like paying two mortgages for one house.

Kerwin Olson, executive director of the consumer watchdog group Citizens Action Coalition, said Indiana lawmakers should have followed the lead of other states.

Many state legislatures, including Indiana’s, were discussing the futures of their energy mixes during the Obama presidency. Some mandated that utility companies acquire a certain percentage of their energy from renewable sources, Olson said.

“We were saying this: We know these coal plants are going to be obsolete in the next 10 to 20 years, investing this amount of money in those coal plants is going to condemn ratepayers to billions of dollars of stranded costs in the future, at the same time that these things will be no longer cost effective,” Olson told State Affairs. “We’re on the record saying that almost 20 years ago.”

Indiana lawmakers and utility companies, though, largely decided against seeking alternatives. Instead, they required Indiana customers to pay to add pollution controls on coal plants — an exact cost that is difficult to quantify but is pegged by the Citizens Action Coalition as more than $12 billion.

“We believe it’s the policy decisions that the state made that led to these escalations and costs,” Olson said. “We decided that the way to comply with these things was to retrofit these massively expensive coal plants. And now here we are in this conundrum.”

Other costs of Indiana’s energy transition

Olson’s skepticism is fueled by the five big utility companies’ profit motive.

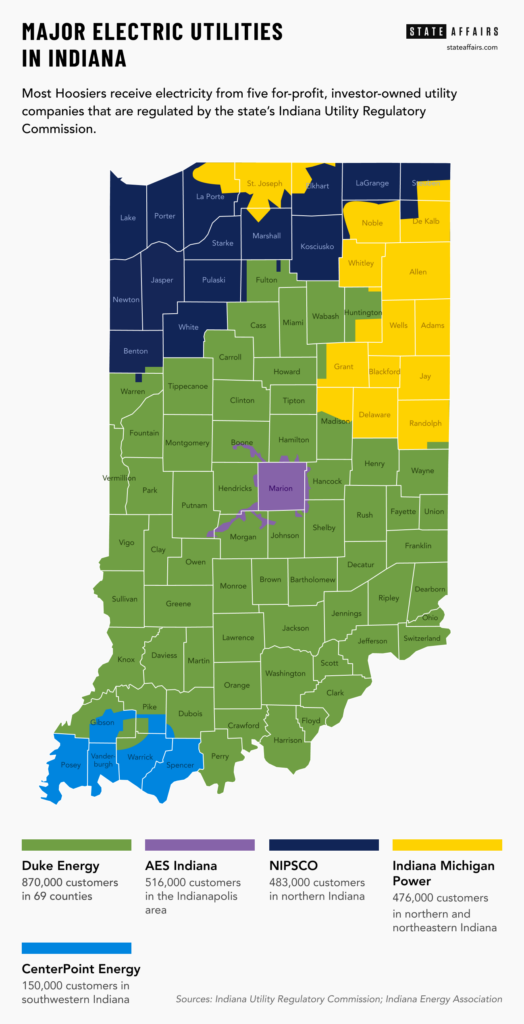

Electric utilities in Indiana, just as in most of the rest of the country, function as monopolies within their service territories. The capital costs to generate and deliver electricity are so vast that most policymakers say it would be too burdensome for consumers to support more than one provider in each service territory.

The five major utility companies, which are for-profit companies owned by investors, are generally able to pass along to customers the costs of generating and delivering electricity. On top of that, the companies receive a certain amount of money that is used to pay for the cost of debt and to generate profits. That’s known as the rate of return.

Consumer advocates like Olson often point out that the five major utility companies in Indiana are incentivized to seek the costliest capital projects because not only are the bills picked up by Indiana customers but the return to investors also grows larger. (In other words: Big, expensive coal plants offer a good return for investors, Olson said.)

Because the utilities as monopolies lack competition, states create regulatory commissions that are tasked with approving most decisions made by the companies.

Ryan Hadley, a former staff employee of Indiana’s commission who now serves as executive director of the Indiana Office of Energy Development, acknowledged some of the challenges identified by the Citizens Action Coalition but thinks the reasons for Indiana’s inflated energy prices are more complex.

Yes, utility companies were confronted with a choice in the early and mid-2000s: Shut down relatively new coal plants as part of Indiana’s energy transition, or spend money to ensure they were compliant with federal regulations.

“The choice was just tough to make, but I’m not sure that there really was going to be an outcome in which customers were going to avoid any sort of rate increases,” said Hadley, who also pointed to other reasons why Indiana’s electricity bills have grown.

The cost to comply with federal environmental regulations went up, Hadley noted, but so, too, did the cost of using coal as a fuel source. And as Indiana tries to play catch-up with new forms of energy, the new costs aren’t being spread around a bunch of new customers.

“Ever since the Great Recession, we’ve had pretty much flat or very little load growth. So when you think of these investments, not only in just replacing and updating our system, but adding these new capital investments, you’re doing that over flat sales and flat growth so you have more dollars being spread over about the same amount of electricity sales,” Hadley said. “So that results in customers paying more than what they did in the past.”

And at the time that Indiana doubled down on coal, other states benefited from hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, which drove down the cost of using gas. States that were reliant on gas came out on top; whereas states that relied almost exclusively on coal did not.

Indiana customers lost their competitive advantage.

Moving away from coal

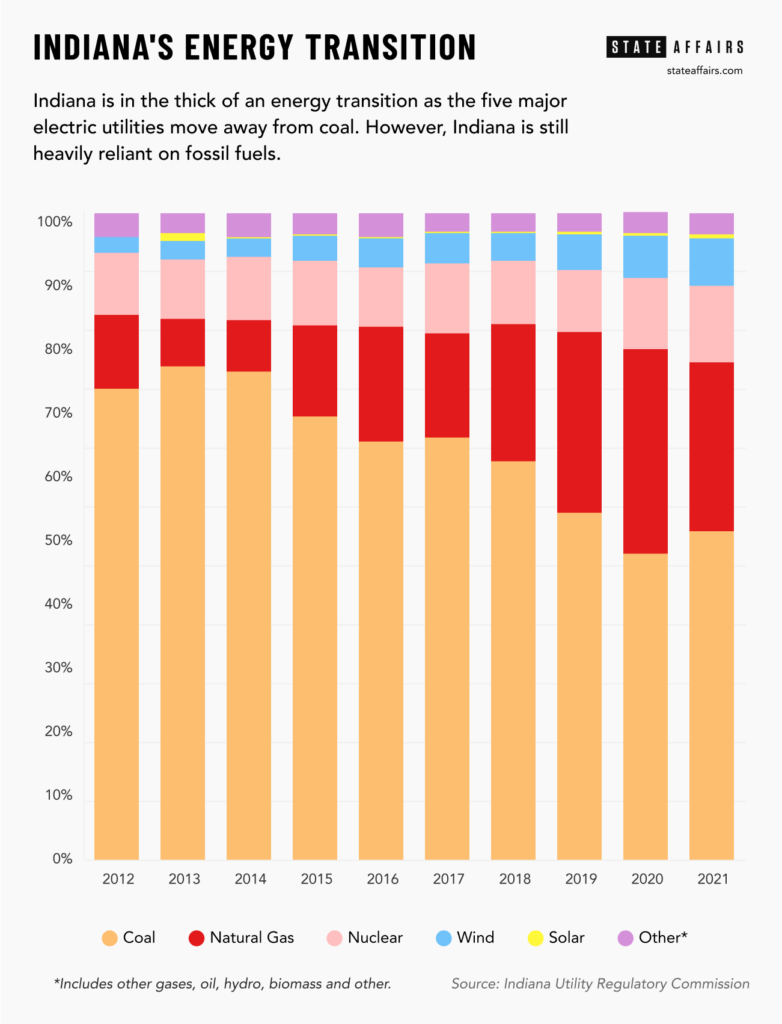

Coal still accounted for about half of Indiana’s energy mix in 2021.

Nationally, the number is closer to 22%, according to the IURC. And Indiana trailed only Missouri and Texas in its usage of coal for electricity.

Still, Indiana’s major utility companies are now moving away from coal. It may be happening a lot later than many wanted, but it’s happening.

Only one of the five major utility companies is planning to burn coal after 2030. Twenty-eight coal-fired units were retired between 2012-21, according to the IURC. Another 21 units are planned for retirement by 2035.

And the state’s reliance on coal dropped by roughly 25 percentage points over the previous decade, according to a State Affairs review of data maintained by the IURC.

Wind and solar grew by a combined 5.5 percentage points during that time, showing an increased appetite for renewable energy. Currently, Indiana trails only Texas, California and New York in the volume of wind, solar and battery storage capacity that’s in development, according to a 2023 American Clean Power Association report.

Hadley, of the state Office of Energy Development, noted that Indiana is operating just under 13,000 megawatts of coal right now. Based on what’s been filed to state regulators, Indiana is forecasted to have an amount close to that — 12,000 megawatts — of wind and solar by 2028.

But that’s another way that Indiana’s energy transition is showing up on residents’ electric bills, at least in the short term.

“We’re in the process of retiring our older coal-fired units, and we have to replace them with something,” said Doug Gotham, director of the Purdue University-based State Utility Forecasting Group. “And that something costs money.”

But as Indiana utilities eye a future dominated by renewables and, hopefully, storage technology, they first are moving fast into another fossil fuel: natural gas.

As coal declined, gas accounted for the majority of new energy produced in Indiana. What accounted for just 11% of the state’s energy mix in 2012 surpassed 32% in 2020, before dipping slightly in 2021.

Natural gas is typically cheaper than coal, utility experts say, and it’s easier to manage for utility companies.

Just look at AES Indiana (formerly, Indiana Power and Light), for example. The company hopes to be the first investor-owned utility company in Indiana to completely exit coal and among the big five utilities is providing the least-expensive residential electricity bills right now.

Gas as a ‘transition fuel’ for AES

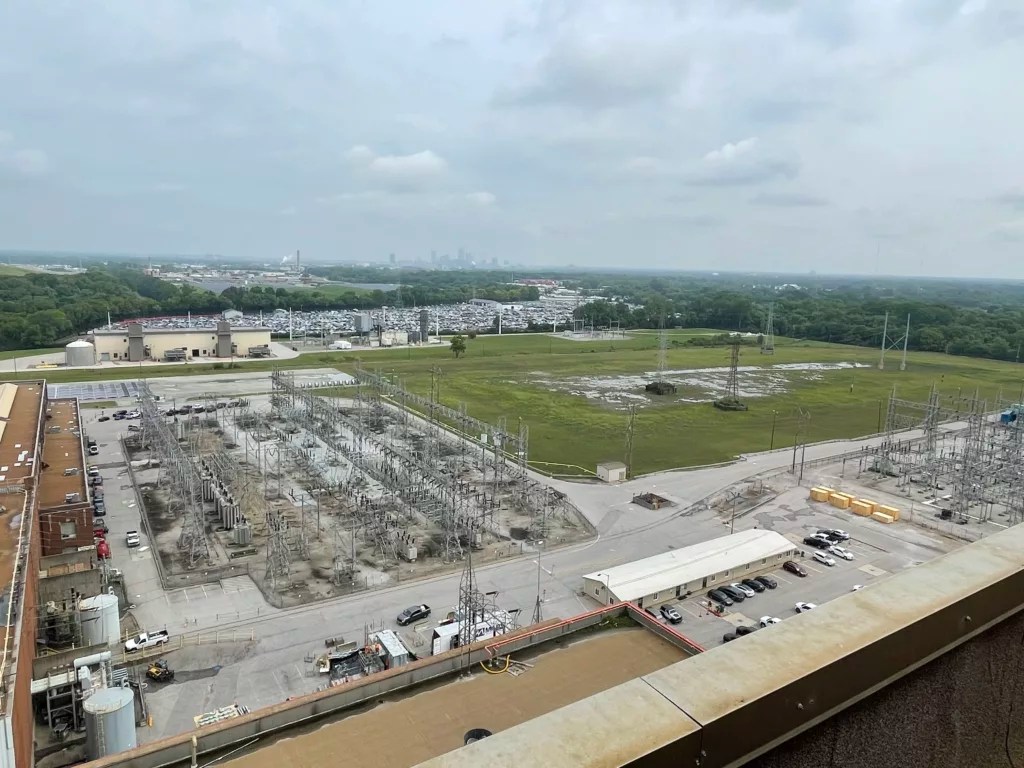

The history of the Harding Street power plant on Indianapolis’ south side dates back to the late 1920s. More recently, some of its units burned coal for decades to produce power.

That is, until 2015 and 2016. That’s when AES converted the plant’s units into gas instead of building a new gas plant.

“The cost of the conversion is very small compared to the cost of building anything new,” Aaron Cooper, AES chief commercial officer, told State Affairs before a tour of the facility. “And I’m not saying insignificant, but I’m saying relatively small compared to building something brand new.”

The savings are found in extending the life of the plant. The original coal units were estimated to run for 30 years, according to Greg Ellis, who manages the plant, but now units that are more than 50-years-old are still providing use. And Ellis estimates that at least 90% of the original equipment was reused.

“You’re extending the life of the equipment that the customers have already paid for,” Ellis said. “We’re buying time to allow technologies to mature without throwing a ton of money at stuff that will be replaced very soon.”

It was the first conversion for AES. Next the utility is looking to retire two coal units at the Petersburg plant in Pike County and convert them into gas.

Beyond the cost savings of using gas over coal, utility experts say the gas units typically can start and stop quickly with no consequence to the machinery. That’s far more difficult with coal units.

To put it simply, a typical gas unit can be turned on, ramped up rapidly and run close to whatever level of energy is needed to meet demand at that particular time. So while an older coal unit would need to run at a high level just in case customers ended up requiring a bunch of energy on a given day, gas units enable utility companies to simply wait and flip the switch when needed.

It’s important to know that not all gas units are the same. Some are designed to work around-the-clock to meet the everyday demands of customers, and others are designed to run only during peak energy times. And some run efficiently; others do not.

Either way, AES is using gas as a “transition fuel” to get away from coal, Cooper said, while working toward an expansion of renewable energy.

Utilities still need something outside of renewables for the times when it’s neither windy nor sunny. Long term, battery storage is believed to be a solution (all excess energy generated by wind and solar could be stored until needed). While the utilities wait for the technology to develop, they will continue to use gas.

Danielle McGrath, president of the Indiana Energy Association, said some reports suggest Indiana utilities could rely on gas for another 40 to 50 years: “That’s simply because the other technologies are not at a scale and availability yet,” McGrath said.

But that line of thinking concerns Olson, of the consumer group Citizens Action Coalition. The group regularly criticizes Indiana’s continued reliance on fossil fuels — and he’s calling Indiana’s “dash to gas” a parallel to the state’s lingering reliance on coal.

“This is the same mistake that we made … when we doubled down on coal plants even though reasonable people understood where the energy markets were going,” Olson said. “There’s a good possibility these things are going to be obsolete in 10 years.”

‘When will it be enough?’

There’s no question Indiana is in the thick of an energy transition. Some observers say it began in earnest for lawmakers and policymakers in 2018 — around the time NIPSCO in northern Indiana shocked the public by announcing plans to exit coal and save $4 billion.

The next year, lawmakers created the 21st Century Energy Task Force to analyze and guide the state’s transition. Four years of work led to HEA 1007 during the last legislative session. It essentially serves as a blueprint for utilities, regulators, watchdog groups and other stakeholders.

Yet even as lawmakers and utilities can look down the horizon and see cheaper, cleaner energy sources, the truth is Indiana is still burning an above-average amount of fossil fuels and Hoosiers’ electric bills are still growing more expensive at a rate that outpaces the national average.

AES says the proposed rate increases would pay for growing maintenance and operational costs caused by inflation, as well as investments into reliability and infrastructure.

To accomplish that, the company is trying to increase the monthly fixed charge, which appears on your bill no matter the energy usage. At the same time, AES also wants to boost the rate of return — the amount that’s typically used to pay toward the costs of debt and to generate profits — from 9.99% to 10.6%.

On the same night that Indianapolis resident Lucille Moore spoke out against the proposed rate increase from AES Indiana, 15 others also voiced their concerns.

Among those in attendance was State Sen. Jean Breaux, D-Indianapolis, who also serves on the Senate utilities committee.

She urged the IURC to be sensitive to how the price increases are harming people in her district.

“I just have to ask: When will it stop?” Breaux asked the commission. “When will it be enough?”

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @StateAffairsIN

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

And check our two-part series on TikTok.

Part 1:

Part 2:

Header image: Aaron Cooper, chief commercial officer, and Greg Ellis, plant manager, during a tour of AES Indiana’s Harding Street plant in August. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

Know the most important news affecting Indiana

Get our free weekly newsletter that covers government, policy and politics that impact your everyday life—in 5 minutes or less.

McCormick, Rainwater attack Braun’s ticket in final debate

In the last gubernatorial debate before the November election, Democratic nominee Jennifer McCormick and Libertarian candidate Donald Rainwater ramped up attacks on Mike Braun and his Republican ticket. The three candidates faced off Thursday during a televised showdown organized by the Indiana Debate Commission. McCormick called Braun’s lieutenant governor running mate Micah Beckwith “the definition …

Rokita: Voter citizenship review may trigger prosecutions

Attorney General Todd Rokita said he intends to use the results of a citizenship status review of nearly 600,000 Indiana registered voters for possible criminal prosecutions. Rokita sidestepped taking a position on whether three justices on the Indiana Supreme Court, which sanctioned him last year, should win statewide retention votes while he spoke with reporters …

7 Indiana down-ballot races and questions, explained

Hoosiers will vote to elect a new governor and the next U.S. president on Nov. 5, but important local races and issues will also be determined further down the ballot. Voters will decide on a constitutional amendment, elect or retain judges and choose new leaders for their local school districts. A full list of candidates …

Voter guide: 9 things to know for Election Day

The general election is less than two weeks away. Here are nine things to know as you make a voting plan for Nov. 5. When do polls open and close? Indiana polls open at 6 a.m. and close at 6 p.m. local time. Where do I vote? Indiana’s voter information website shows voters their polling …