Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoWhy nature preserves are good for Indiana

A pearl crescent butterfly at Hoosier Prairie Nature Preserve, on Wednesday, August 10, 2022, in Schererville. (Credit: Indiana Department of Natural Resources)

John Bacone made it his life’s work to see Indiana protect some of its most natural and undisturbed areas — and he did that through his work as the director of the Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Nature Preserves.

When he started, the state was home to 46 preserves. Bacone dreamed of one day reaching 225.

Indiana has now blown past that number, with Toothwort Woods in Jennings County this month becoming the state's 300th nature preserve.

Bacone, 74, is from Chicago but he started his career as a naturalist at Turkey Run State Park.

“That's when I got to understand how great and beautiful Indiana was,” Bacone said.

He then worked in Illinois to inventory the last remaining natural areas in the state before returning to Indiana in 1977 to become the division’s assistant director. Three years later, he took over as director of the division, holding that job until his retirement in 2019 — and by then the state had reached 287 preserves.

In an interview with State Affairs, Bacone explained why Hoosiers should protect the state’s natural areas, how they can support those efforts and which ones are his favorites to visit.

The conversation is edited for clarity, brevity and length.

Q. What is the purpose of nature preserves?

A. They are habitats for some of Indiana's rarest types of natural communities. At Turkey Run State Park you have floodplain forests, ravine forests, upland forests, fens and seeps, cliffs. And each one of those kinds of habitats supports some different and unique species.

And when you go to the northwest part of the state, you have prairies and savannas. And when you go to the northeast part of the state, you have lakes and huge marshes. And when you go to the southern part of the state you have cypress swamps, and we have caves and large forests and Brown County and so on.

So the purpose of the nature preserves was to try to find and protect the least disturbed examples of those varieties of habitats. And by doing that, you usually can get some of the rare species because that's the kind of habitats they live in. So that's the main purpose of it; and then it's to set them aside for the benefit and enjoyment of future generations. The Legislature, when they passed the law, they wanted to be sure some of the Indiana that we inherited — our heritage, when the first settlers came here — would still be there on into the future for people to see where we came from and where we're going.

Q. Can you tell me more about the Nature Preserves Act in Indiana?

A. It was passed in 1967. A dedicated state nature preserve is the highest level of protection a piece of ground can have in the state. It's got more protection from a conversion for another use than even a state park does because of the way the law is written. It says you can only take a piece of a nature reserve for an unavoidable and an imperative public use, and then only with the approval of the Natural Resources Commission and the governor.

So regardless of if this land changes ownership, that's always staying with the property. So a new owner has to honor those things that are in there. So it's intended to be kept in its natural condition forever. And the other thing the Nature Preserves Act does in Indiana, which is really great: It's regardless of ownership and, in fact, the act encourages all owners of natural areas — be it the city or county park departments, colleges or universities or other entities — it encourages them to dedicate their land and they can be given that protection under the Nature Preserves Act. A lot of these places would have never been protected had it not been for one of those partners going out of its way to acquire the land and then see that it continued to be protected.

Q. Indiana values economic development and new jobs, but it seems like the state also has this culture of valuing natural areas.

A. state parks that were acquired — places like Turkey Run, Shades and McCormick's Creek — were big, large, natural areas. But the economy and ecology go hand in hand.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources is involved with the environmental review process. The state has a natural heritage database and that gets checked: Like, what are some of the rare species? Basically, the entities that want to develop, they don't want to have a big fight and destroy high-quality things so they get involved early on and look for a route — like the new Interstate 69 or a new factory that's proposed somewhere — and they find out that they can pick the alternative that's minimizing any kind of environmental issues at all.

Q. What’s the difference between a state park and a nature preserve?

A. Well, in general, the state parks are striving to have a way to afford recreation so people can enjoy the resource. But you know, a big part of what they're doing is having an infrastructure, maybe it's an inn, some campgrounds and some trails. And then the nature preserves are set up within the parks' master plan. Parks are set up to encourage and establish appropriate recreation, and then the nature preserves are established within the parks to help parks maintain the balance because their vision for the future also includes having significant parcels of parks stay natural because that's a big part of why people come to the parks.

Q. Can people visit nature preserves?

A. Almost all the nature reserves. For instance, Acres Land Trust just closed a few trails on some of their properties just because they're getting overused and they want to give the area the right to recover. Sometimes nature preserves are not opened yet — the key word being “yet” — because for instance, when the Division of Nature Preserves buys a site, we have to try to find a way to provide appropriate parking.

And then there's a category of nature preserves that are actually just too fragile. For instance, a ‘fen’ is a type of wetland that contains a number of rare species and it's just a mucky, boggy substrate. If you can't put a boardwalk on it to get a boardwalk right up to it, you really don't want people going through it because it can get ruined in a hurry. And then there's a few caves that have Indiana bats or other federally listed species that are just not allowed by federal law to be open. They're only open when the biologists go in and do a count to try to figure out how many bats are in the cave. But the vast majority of nature preserves are open.

Q. What are your favorite nature preserves?

A. That's like trying to pick your favorite albums. One of my favorites is the Hoosier Prairie Nature Preserve, which is in Lake County, and it's a fairly large complex of prairie, savanna and wetland. It has a nice trail and parking lot.

Another one of my favorites is the Bluffs of Beaver Bend, which is a really neat area in Martin County near the town of Shoals that has a really nice trail in it. And it's about a mile of fringe along the White River and it has almost a mile of 50- to 100-foot high sandstone bluff next to the river, so it's just really scenic.

And I guess the third one is Portland Arch Nature Preserve. It's got a natural arch and some beautiful sandstone canyons and it's located near the Wabash River in Fountain County.

Shrader Weaver Woods in Fayette County is a beautiful old growth woods that has a really nice hiking trail and parking lot. The woods were protected by the owners for years. They refused to sell it. They didn't want money. They just wanted it to be protected. And eventually they gave it to the Nature Conservancy who gave it to the state to be a dedicated nature preserve.

Q. How can Hoosiers support nature preserves?

A. So one thing is to buy the environmental license plate. The funds from that go to the Benjamin Harrison Conservation Trust which is set up to fund land acquisition. Or they can donate land to any land trust.

Another thing: Nature preserves and state parks have volunteer days — and so do some land trusts where they try to get volunteers to help them with invasive species control and things like that. And I know nature preserves love to have hikers report, you know, 'Hey, I saw you might have a problem' here or there so they can learn, because they have regional ecologists who are responsible for a huge part of the state. So anytime we have anybody else who could be the eyes and ears, and even including doing plant inventories and other things. They really appreciate that.

Contact Ryan Martin on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: A pearl crescent butterfly at Hoosier Prairie Nature Preserve, on Wednesday, August 10, 2022, in Schererville. (Credit: Indiana Department of Natural Resources)

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

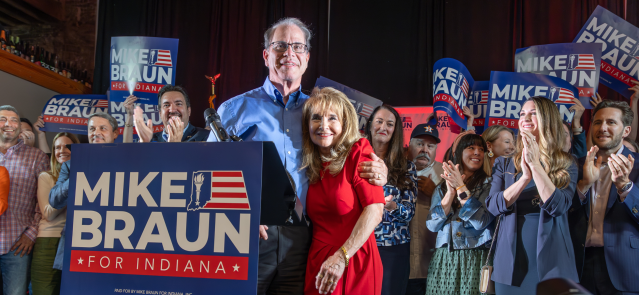

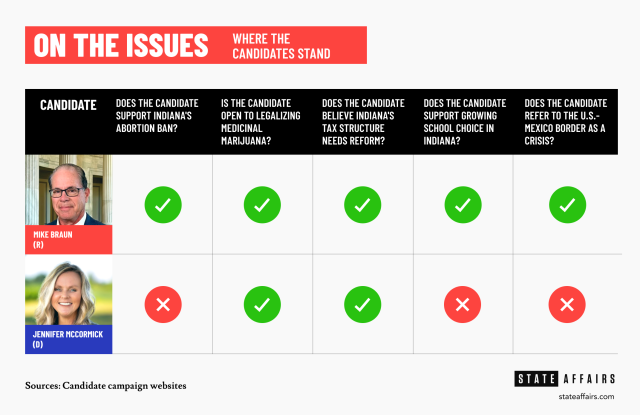

How McCormick, Braun view abortion, taxes and other key issues

A Democrat-turned-Republican and Republican-turned-Democrat will soon face off in the race to become Indiana’s next governor.

Sen. Mike Braun, who voted as a Democrat prior to 2012, captured the Republican nomination in Tuesday’s primary. Jennifer McCormick, formerly a Republican Superintendent of Public Instruction, will represent the Democrats.

Voters will decide the state’s next chief executive in November.

A State Affairs analysis of the candidates’ campaign platforms and public statements found key differences — and a few similarities — in their planned approaches to a variety of issues impacting Hoosier voters.

Here is how they match up.

Abortion

Braun: As a senator, Braun has long supported abortion restrictions.

In 2020, he called for the Supreme Court to re-examine Roe v. Wade.

In 2023, he proposed federal legislation that would have required parental notification before any unemancipated minor could seek an abortion. He said at the time: “Hoosiers put their trust in me to stand up for the unborn, and that’s what I’ve been proud to do every day in the Senate.”

He has since signaled support for the state’s abortion ban. His platform reads: “State lawmakers must work to ensure the gains we have made to protect life are secured and strengthened.”

McCormick: In a Tuesday interview with State Affairs, McCormick said her candidacy represented a referendum on reproductive rights.

“I’m going to fight to restore those rights under any authority I can, working in a bipartisan fashion, using our committees, board and our agencies. I also know, too, what everybody’s fear is: that they’re [Republicans] not going to restore those rights and will take [restrictions] further.”

From her platform: “Indiana’s Republican-led extreme abortion ban has taken away the right of women to make deeply personal decisions regarding their own health care.”

Marijuana

Braun: At a March 26 Republican primary debate, Braun suggested an openness to legalizing medicinal marijuana.

“It’s gonna hit all of us. I’m gonna listen to law enforcement — they have to put up with the brunt of it,” he said. “Medical marijuana is where I think the case is best made that maybe something needs to change. But I’ll take my cue from law enforcement there as well. … I hear a lot of input where [medical marijuana is] helpful, and I think that you need to listen and see what makes sense.”

McCormick: The Democrat’s platform also addresses medical marijuana legalization, while speculating on possible recreational use.

“We will fight for the legalization of medical marijuana as a source of state revenue established on a well-regulated marketplace and monitored by a Cannabis Task Force in order to study the issues, opportunities and potential obstructions associated with recreational marijuana legalization.”

McCormick said she would also support expunging low-level marijuana-related convictions.

Taxes

Braun: At a March 19 National Federation of Independent Business forum, Braun said the state’s property tax system “went out of whack because it couldn’t respond to inflation like we’ve never seen before.”

“The way you finance any lower taxes would be to bank on the government being run more efficiently,” he said.

His platform also calls for government spending cuts to finance lower taxes: “Reducing the size of government is the key to cutting taxes, and Mike Braun will work through every state agency to find ways to save money while delivering high-quality services to taxpayers.”

McCormick: McCormick also spoke about taxes at the March 19 forum.

“I agree with a revamp of our taxing system,” she said. “But also it’s about not just how we’re getting our revenue, it’s about our expenditures. Yes, we need to fix our gas tax. Yes, we need to look at the income tax. But here’s the thing: There are hidden taxes we’re not having a conversation about.”

Her platform also references the possibility of combining state agencies as a way to save money.

Education

Braun: In his platform, Braun supports broadening school choice and parental rights.

“As a former school board member, Mike Braun knows parents are the primary stakeholders in their children’s education and every family, regardless of income or zip code, should be able to enroll in a school of their choice and pursue a curriculum that prepares them for a career, college or the military,” the platform reads.

Braun also pledged to ensure critical race theory and discussions about gender are banned in public schools.

McCormick: Education is one of McCormick’s primary issues, according to her platform.

She calls for the elimination of statewide testing, increased early childhood reading and child care options and a minimum base salary of $60,000 for all K-12 teachers.

McCormick also addresses the state’s school choice movement.

“We will call for a pause in the expansion of school privatization efforts while requiring fiscal and academic accountability and transparency for all of Indiana schools that receive public tax dollars,” her platform reads.

U.S.-Mexico border

Braun: Braun’s television ads have touched on border security, and his platform calls for increased focus on the area.

“Joe Biden and the left have created a humanitarian and national security crisis on our southern border,” the platform reads. “As governor, Mike will continue to support and enact the America First policies that were working. Otherwise, every town will become a border town.”

McCormick: McCormick’s border-related plans are more focused on facilitating legal immigration.

“We will work with local, state and federal officials in supporting an immigrant system that creates a safe, timely, orderly and humane pathway for those seeking legal immigration while keeping our communities and those responsible for border security safe,” her platform reads.

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

Spartz, Shreve, Stutzman win Republican congressional primaries

A central Indiana congresswoman successfully fought off eight primary challengers, while crowded races for three other Republican-leaning congressional districts began to clear in Tuesday’s primary election. And in northeastern Indiana, a former congressman held on in a tight race as he seeks to return to Congress. All of the state’s nine U.S. House of Representatives …

Mike Braun wins the Indiana Republican nomination for governor

U.S. Sen. Mike Braun was declared the winner of the Republican gubernatorial nomination shortly after polls in Indiana’s Central Time Zone closed. With 98% of votes counted as of Wednesday morning, Braun had 39.6%, followed by Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch with 21.8%, Brad Chambers with 17.5%, Eric Doden with 11.9 %, Jamie Reitenour with 4.8% …

Here’s how to vote in Indiana’s primary election

Thousands of Hoosier voters will head to the polls Tuesday, May 7, for Indiana’s primary election. This year’s ballot includes a competitive contest for governor, as well as dozens of state and federal legislative races and a few school referenda. The primary will decide which candidates will represent their respective parties in the Nov. 5 …