Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoJay Chaudhary optimistic about Indiana’s changing approaches to mental health and addiction

Jay Chaudhary is the director of Indiana's division of Mental Health and Addiction. (Credit: Indiana Family and Social Services Administration)

When Jay Chaudhary became director of Indiana’s Division of Mental Health and Addiction in 2019, he was told to give himself six months to learn everything.

Six months later came March 2020, and everything changed.

The crises spurred by COVID-19 exacerbated many of the mental health and addiction challenges that Hoosiers were already facing.

Chaudhary is quick to note, though, that the pandemic also elevated everybody’s understanding of the need to seek help. The heightened awareness is also leading to policy responses from Indiana state government.

For Chaudhary, it’s a positive change. When he previously worked as an attorney for the nonprofit Indiana Legal Services, he provided civil legal help to patients of mental health providers. He witnessed the daily challenges they were confronting.

Now he’s in a position to enact change at the state level to alleviate some of those challenges.

Chaudhary this month spoke with State Affairs about the state’s new approaches to addressing mental health and addiction, including the creation of the 988 crisis hotline and mobile crisis teams.

“There are good reasons to be optimistic about this,” Chaudhary said. “We have everybody on the same page rowing in the same direction. I do think there’s a real case to be hopeful.”

The conversation is edited for clarity, brevity and length.

Q. Did you know how important your job was going to be when you took it?

A. Yes, I definitely had sleepless nights the first two or three months of the job because of the immense responsibility of trying to figure out how to build a system that helps Hoosiers who are in some of our most vulnerable situations.

But I don’t think anybody could have anticipated the corresponding impact that COVID had on these issues, not only from just a human suffering standpoint in terms of increased overdoses, increased mental health issues, but also like a spotlight situation. All of a sudden we’ve found ourselves in a situation where everybody’s talking about mental health. Which is fantastic, it’s wonderful, but then the task remains: Well, OK, now that we’re talking about it, how do we actually do it?

Q. What are some of the ongoing challenges tied to that period of COVID?

A. The truth is there was a massive disruption in how we live and work and interact with each other. And anytime there’s a massive disruption like that, I think things that were bubbling under the surface, there’s a chance they can come up front and center.

That’s what happened with mental health. We were already seeing, for example, massive increases in teenage anxiety and depression and increased rates of suicide attempts, especially for teenage girls. And I don’t think a disruption like COVID helped that trend at all.

But I think part of it is that they could shine a spotlight on these things because all of a sudden everybody was dealing with some degree of mental distress during that time period — which I think has led to increased awareness and reduced stigma. Reducing stigma is the key to getting more people into the care that they need. The flip side of it is that reduced stigma leads to increased demand, and we have to figure out how to meet it.

Q. There seems to be a growing awareness and willingness among Hoosiers to talk about mental health and addiction. It hasn’t always been easy to talk about. Beyond COVID-19, what else is driving that?

A. We, as people and human beings, are the main characters in our own stories. When issues burst into our own little bubble, we’re necessarily going to start paying more and more attention to it. As a result of a lot of different factors over the last 15 to 20 years or so, addiction and substance use disorder were no longer something that wasn’t affecting most people.

We had legislators and executives and people from all walks of life out sharing stories about their cousin or their nephew or their brother or their sister or their son or their daughter that was affected by addiction. And you saw that all come to a head in the mid-2010s where we saw a long overdue change in terms of viewing substance use disorder as something that was to be met with a punitive and then carceral solution versus something that was a disease that was worthy of compassionate treatment and care.

That change is probably a long time coming and we can’t overlook the element of now this is happening to people who are wealthier and more well-off and everybody’s dealing with it now. And so I think you’ve seen the impact of that attitude shift in terms of building up resources, in terms of building up attention, in terms of changing policies to make them more recovery friendly.

I think the same thing is happening for mental health. There was this notion of being stoic and sucking it up and just moving on and soldiering on. And now I think people are reevaluating that perspective and seeing that this is also a disease, treatment is available, treatment is possible. It’s possible to get better and I think you’re seeing the same sort of shift — and not just attitudes, but also corresponding policies and structures to help with this.

Q. You mentioned policies that are recovery friendly. By that do you mean policies that acknowledge that recovery often means setbacks? And giving someone more than one chance?

A. Absolutely, we always say recovery is not linear. Setbacks are common.

A big part of that is educating employers and other folks that look, if you have somebody who is in long-term recovery, first of all, recovery is possible. So this is not something that because they had a problem once, they’re always going to have a problem.

I think also that you see that trickle into the criminal justice sphere, for example, with drug courts. It used to be with drug courts it was one dirty drug test and you would be met with more punitive consequences. Now judges and other folks in those courts are a lot more compassionate and understanding and working toward solutions as opposed to being punitive in nature.

Q. Do you still hear from people who have misconceptions or misunderstandings?

A. From time to time. I try to deal with those folks with some compassion as well, because I think that those misconceptions come from a place of having been hurt or having been burned, frankly, by somebody who had a problem. It’s not hard to see how you can harden your perspective in those situations. And so our approach with those things is always just let’s educate, let’s have a conversation, let’s see if we can come to some agreement.

Everybody more or less wants the same things. We want safe, healthy communities and opportunities for our loved ones and families.

Q. How is the 988 hotline coming along? What’s next for its implementation?

A. Thanks for asking about that. So 988 is the three-digit suicide hotline number that went live in July 2022. We’re approaching this by building a system in three parts.

For example, when you think about 911, you don’t just think about the number, you think about the police and EMS and emergency rooms. And so we’re envisioning a similar system for 988, where we have someone to contact, so that’s the call center — which also includes chat and text functions — but then also someone to respond, which are mobile crisis teams; and a safe place for help, which are what we call crisis stabilization centers, which are kind of therapeutic environments where folks can be taken in that aren’t the ER and aren’t the jail.

So that’s a three-part system that we’re working on building. Now, “building” is the right word — we have to build this up from almost nothing. It’s going to take a long time. And so the first part of that system was someone to contact; it’s probably the furthest along. We have soon-to-be five 988 call centers that are going to migrate to a single platform so no matter where you call from in the state of Indiana, you’re going to get one of these high-quality, trained call centers.

We’re also making progress on the other two parts of it. We’re going to pilot four mobile crisis teams that cover 15 counties in 2023, to see what we can do and learn from that process. We’re also going to be funding several crisis centers where again, we can pilot, we can learn and we can ultimately build a system that works for Hoosiers.

Q. What is a mobile crisis team?

A. We’ve tried to maintain as much flexibility for local communities to build the team that reflects their resources and their actual needs. But we also wanted to maintain the presence of a peer on those teams because we strongly believe — and I think it’s a pretty wide consensus in the field — that the presence of a peer of somebody who’s been through this system before or has been through this situation before is the key to rapport building and de-escalation.

What we’ve done is — with our partners in the Legislature — is say your crisis team has to have a peer on it, and then they could have one of the other professionals on it, like a police officer or EMS or social worker or a higher level clinician. And then it has to have clinical supervision. And so that structure kind of strikes the balance between local flexibility but also maintaining a degree of oversight and rigor in that process.

Q. In the last budget, state lawmakers directed $100 million in federal funding (through the American Rescue Plan) toward mental health. How was that money spent? Did we see positive results?

A. We’re still spending it. The nice thing about this money is that it will last us through about 2026 so we can be a little bit thoughtful about it.

The challenge with one-time funding is you don’t want to create those cliffs because you can pay for a bunch of services for a short period of time and then what happens? Sometimes we actually leave people worse off than before if you build all these programs with no kind of feasible path to sustainability.

But I think we’ve invested in some pretty thoughtful and smart, impactful ways. And I think that we’re constantly evaluating it. First is building sustainable infrastructure around the state. And so we’ve invested some of that funding but also some other funding in our 988 system in order to build up that infrastructure.

We’ve also tried to invest, in partnership with local units of government but also locally driven organizations, to increase access in their communities. Our big push there was our Community Catalyst grant program where we ended up spending around $30 million of this funding, but it was matched by almost the same amount of local funding to give grants to local organizations to provide services in a variety of areas related to behavioral health.

Another big push for us is workforce because ultimately without a behavioral health workforce, we’re not going to be able to get the outcomes and the access that we desire. So we’ve done things like invest in residency programs, we’re putting out another locally driven request for funding proposals for innovative ways to build the workforce pipeline.

Q. What is the business or economic impact of mental health and addiction in Indiana?

A. As part of the Behavioral Health Commission, which I was the chair of, we engaged a group of researchers from Indiana University to study the cost and impact of untreated mental illness on the state of Indiana.

And the number they came up with was $4.2 billion a year. Pretty remarkable finding. Just for context, that’s more than the amount that corn — which is the signature crop of Indiana — brings in every single year.

It is manifesting in huge costs in various places: in the emergency rooms and jails, Department of Child Services, all of these other places. But I think if you step back for a second and if you look at the benefits side of things, a workforce that is taking care of their mental health and is able to access treatment when they need it and able to recover from potential substance use disorder challenges and setbacks is a much stronger and healthier one for Indiana employers and businesses.

We do see this as a big-picture quality-of-life issue. You want your loved ones who are in a crisis to be responded to with compassion and a therapeutic approach. You want your employees and your human capital to be operating at their full potential. And we think that one of many tools to be able to do that is creating a behavioral healthcare system where people can access the care when they need it.

Q. For regular Hoosiers reading this interview, what are a couple things they can do right now to help with some of these challenges?

A. In terms of stigma, I think we’ve made a lot of strides thanks to a multi-sector approach to really reducing and addressing the notion of stigma, but that doesn’t mean we’re anywhere close to where we need to be.

Having conversations in your local communities about mental health and also about the notion that it’s OK to seek help, it’s OK to seek treatment, is really, really important. And that’s something that we as a [state government agency] can’t do. That has to come from people and local communities and faith organizations and employers and schools and the glue that holds our communities together.

Have those conversations. Make it clear that if you are struggling, you should seek help. And also offer some trainings and education to folks about mental health literacy: What are some signs? What are some indicators that somebody needs help?

Our job at the state is to help create a system where people can access the care that they need, but ultimately we need people to be able to identify that they need help in the first place, and that’s something that has to happen at the local level.

Do you have a request for a Q&A with another Indiana policymaker? Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, or at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, which has trained listeners standing by and ready to help. Visit 988lifeline.org for crisis chat services or for more information.

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

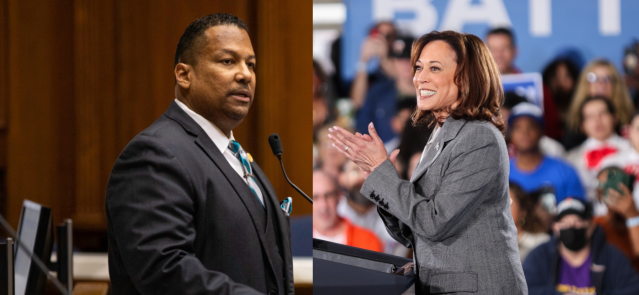

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …