Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoIndiana’s public access counselor on law enforcement, school curriculum and why government is messy

Indiana Public Access Counselor Luke Britt in his office in March 2023. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

Luke Britt jokes he was “plucked out of obscurity” by former Gov. Mike Pence in 2013 to become Indiana’s public access counselor. He was a rank-and-file employee, unaffiliated with the administration or any political party.

“I think they wanted to do that to establish some independence and credibility for what’s supposed to be an apolitical, neutral, objective office,” said Britt, 43, an attorney who has since been reappointed twice by Gov. Eric Holcomb. “I get complaints against state agencies all the time and there’s never been a moment where I’ve thought my independence has been called into question.”

As public access counselor, Britt essentially serves as a referee who calls fouls on public officials who are violating Indiana’s access laws, including ones governing public records. Hoosiers can file complaints with his office when officials fail to disclose public records or when they generally conduct government business in closed-door meetings.

Much of his time, though, is spent training people — whether they are government officials, journalists or other members of the public — on access laws. And with only three people in the office, he stays busy.

“If you want a quick answer from subject matter experts, you don’t have to look far to find it,” Britt said, “or to fight through layers of bureaucracy to get to somebody with the answer.”

In honor of Sunshine Week, which began Sunday, State Affairs talked to Britt about Indiana’s public access laws, as well as the topics that are most on the minds of Hoosiers, including law enforcement and school boards.

The conversation is edited for clarity, brevity and length.

Q. How do public access counselors celebrate Sunshine Week? Do you throw open some government doors somewhere?

A. It’s always interesting to see other states’ access laws, and I will say that Indiana is uniquely positioned with this type of role. Sometimes it’s only for local governments. Sometimes it’s for just state government. Sometimes it’s under the Attorney General’s Office, which we are not, or it’s under another political office. The way we do it, I think, is pretty wise.

Q. Why’s our way better?

A. To maintain that neutrality and that independence and objectivity. If I had to report to an elected position with a certain ideology, that might compromise my ability to interpret the law from that arm’s length, objective perspective.

Q. Why is it important that Indiana has an established law for public records and open government meetings?

A. Fundamentally I think that transparency breeds accountability. If you’re approaching public service with the mindset that all of our trust and resources come directly from the public we serve, then the way to be accountable to that trust is by demonstrating what we do on a regular basis. How are we using those resources? How are we administering the programming that we’re entrusted to do? And are we doing it well? And I think that documentation and open meetings all play into a way to preserve the fidelity of that accountability.

Q. How does Indiana’s public records and open government law compare to other states generally?

A. It kind of depends on the subject matter. If you’re talking about body cameras, you’re not going to find a model code anywhere across the country, and different jurisdictions treat that footage differently. Same with law enforcement records, same with school boards, or trade secrets or you name it.

Our law is not comprehensive when it comes to each and every document that can potentially exist or each and every iteration of a meeting. It’s a little more amorphous. Having a public access counselor to interpret what the General Assembly’s intent was is important, because fortunately for me they put my marching orders right there in the statute.

That guides my perspective, from a legal standpoint: You can’t treat the laws as they’re written with a strict constructionist approach. You have to lean into some practical considerations.

And there are some ambiguous terms there. Not everything’s completely totally defined, but my marching orders are to define those undefined terms in a light most favorable to transparency.

Q. Do you hear about law enforcement from people who contact this office?

A. Probably the number one area that we address are law enforcement issues, just because it’s so complex. We’ll get a number of calls a day about a local police department or county sheriff’s office that we have to navigate. And one of those undefined terms would be when something’s compiled in the course of an investigation of a crime, does it ever become disclosable? Because right now, during the pending investigation, at least, law enforcement has very broad discretion to deny a records request if it would compromise the underlying investigation.

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) at the federal level, for example, has a bookend: Once the investigation is over, then it’s potentially disclosable unless there’s some other state secret in there. But in Indiana, we don’t have that. We do have some language that says withholding the record — any kind of record, law enforcement or not — you can’t be arbitrary in applying your discretion. So there’s a tension there.

And some law enforcement agencies take the approach that hey, once the investigation is over, especially if a prosecutor has adjudicated the crime, why not give that out? But others are a little more sensitive about keeping it in-house and that’s where we might have to do some convincing and persuading. Sometimes successfully, sometimes not.

Q. I know that’s frustrating for journalists, but I bet it’s frustrating for other people too.

A. We deal a lot with folks who will contact us saying we had a family member that was murdered 50 years ago. And it might be a cold case, it was never solved, but we never got any closure because we never got any information. There was no trial to go to and to hear about what’s going on and the efforts that law enforcement made and so yeah, I think that kind of scenario is rather heartbreaking. Because they don’t get that closure, and that’s tough on some folks and understandably so.

Q. How often do you find yourself mediating between two sides?

A. That’s every day. I just got back from South Bend and there’s a lot of tension right now up there between the clerk’s office and the common council. And so they asked me to come up and referee a session where we hashed everything out, put everything on the table and tried to get to a place where we could all come together and say, you know what, we’re serving this community and that’s the most important piece.

But every day we’re trying to move the needle on some kind of conflict or some kind of dispute, to find some kind of common ground. And again, just like everything else, sometimes that’s successful and sometimes not.

Q. Without that role being performed, would we otherwise see a lot of unnecessary filings in court?

A. Yeah, I think that was the original intention behind the establishment of this office, to be a buffer between the judiciary and these disputes. Now do lawsuits get filed? Yeah, both with and without our initial involvement, but I’d like to think that we do provide that buffer and we’re able to resolve things without the expense of going to court.

Q. What are some of the most common disputes or misunderstandings you come across?

A. Law enforcement is going to be the most common. I’d say that takes up about a third of all of our disputes. The schools are probably number two, especially recently, with some of the issues surrounding curriculum and the conversations that everyone’s having based on that kind of thing. A parent might want to see a textbook or to go inspect a science book. And some schools have it so you don’t even have to make a public records request; they just put everything out there and say, ‘OK, here are all our materials. Community, scrutinize it all you want.’ Neither way is right or wrong, but some are just a little more proactive than others.

We do a lot with trade secrets. You know, especially with third-party private sector vendors that are doing business with the state, and they submit materials either through the bidding process or negotiation process that have a lot of sensitive information in it. So once it’s submitted to an agency it is presumptively a public record, but then you’ve got to figure out: Well, did they give away their secret sauce when they bid on a software proposal?

Q. I’m assuming you get contacted quite a bit by journalists for stories we’re working on. What about people who don’t work as journalists?

A. We find that about 55% of our requests come from other public officials or public employees. So they’re reaching out to say, ‘Hey, how do we do the right thing in this circumstance?’ Rarely is it, fortunately, ‘Hey, how do we hide this document? You know, how do we keep it in-house?’ But most of the time, it’s just an honest good faith question.

And then the next largest demographic would be non-media, just questions from the public. And then I’d say about 15% of our work originated from journalists. Fortunately, we have the Indiana Broadcasters Association and the Hoosier State Press Association that can answer a lot of those questions.

Q. When public officials are contacted by you, are they typically happy to hear from you? Or are they annoyed by the incoming lecture?

A. I think most are willing to listen and, actually, if we need a course correction, they will cooperate. I think we’ve leveraged a decent reputation in order to be effective like that. Some are suspicious, some, especially in rural communities, have no idea who we are or what we do. They’ve never heard of our office before.

We only find a violation in about 35% of all cases, so 65% of the time, they’re doing the right thing.

Q. For Hoosiers who are not journalists who want to get more involved in how local or state government works, what are some resources or some steps they can take?

A. It’s the same advice I give to journalists: Build professional relationships. Know the personalities. Public officials are people, too; public employees are people, too. There’s a certain attitude that yields more success than others and usually, that’s being professional and understanding the process.

That’s a lot of what we do, educating the public on what these various types of government entities do. I think there’s some misconception between, for example, what a school board does versus what the administration does. And that’s the same thing with any layer of bureaucracy. What do county commissioners do versus the council or city council versus the mayor’s office?

Just educating the public on just the role of government is big. And so, if you’re armed with that knowledge before you go and seek to engage, that can be helpful, as well. Same goes for journalists.

Q. Going back to school curriculum — which has been in the news the last couple years, is that fueling a rise in disputes and questions?

A. I think that that generated a lot of engagement that wasn’t there before on the part of parents and community members who, one way or another, got wind of certain issues, and they wanted clarity. Part of that was just like I said before, encouraging them to approach it with a modicum of civility. And we did put out a lot of statements around that time that screaming at a school board meeting doesn’t always yield the best results.

Those are the outlier situations but just one example of how a measured approach can often be more successful. And that’s not a public access thing, that’s just a human nature thing. But oftentimes, those two things are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Q. I once lamented to a former journalism professor about how long it was taking to receive public records. He calmed me down by noting that no one promised democracy would move fast.

A. That’s a good point. And it’s not streamlined either. It can be messy. It can be clumsy, and I think sometimes by design. I kind of cringe sometimes when I hear sound bites of people saying government should be run as a business. We’re not a profit-making exercise. We don’t have widgets necessarily. We can be run in a businesslike manner, but it’s not a business. It’s something different. And it can be weird and clumsy and sloppy sometimes. But again, some of that is by design, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Q. On the topic of clumsy and sloppy, is there something in the public access law that you wish was less ambiguous?

A. Yeah, there are all kinds of things and I don’t know that that’s necessarily my place to say publicly. I have those conversations sometimes with legislators or with the administration.

I keep my own perceptions and biases to myself so that I can remain independent and objective when I’m writing those legal opinions because ultimately I interpret the law and, to the extent it’s inappropriate, I don’t like to fill in the blanks with my own preconceived biases.

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

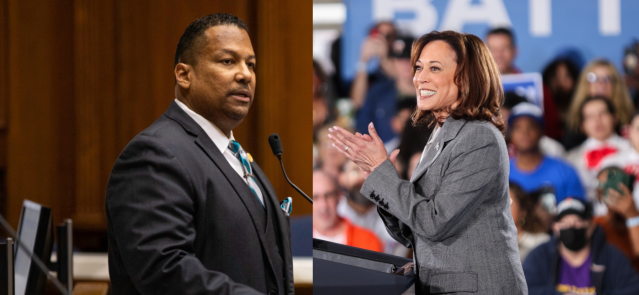

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …